Weather ship

A weather ship, or ocean station vessel, was a ship stationed in the ocean for surface and upper air meteorological observations for use in weather forecasting. They were primarily located in the north Atlantic and north Pacific oceans, reporting via radio. The vessels aided in search and rescue operations, supported transatlantic flights,[1][2][3] acted as research platforms for oceanographers, monitored marine pollution, and aided weather forecasting by weather forecasters and in computerized atmospheric models. Research vessels remain heavily used in oceanography, including physical oceanography and the integration of meteorological and climatological data in Earth system science.

The idea of a stationary weather ship was proposed as early as 1921 by Météo-France to help support shipping and the coming of transatlantic aviation. They were used during World War II but had no means of defense, which led to the loss of several ships and many lives. On the whole, the establishment of weather ships proved to be so useful during World War II for Europe and North America that the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) established a global network of weather ships in 1948, with 13 to be supplied by Canada, the United States and some European countries. This number was eventually cut to nine. The agreement of the use of weather ships by the international community ended in 1985.

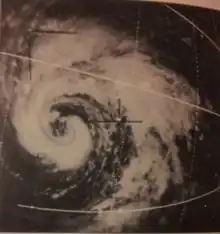

Weather ship observations proved to be helpful in wind and wave studies, as commercial shipping tended to avoid weather systems for safety reasons, whereas the weather ships did not. They were also helpful in monitoring storms at sea, such as tropical cyclones. Beginning in the 1970s, their role was largely superseded by cheaper weather buoys. The removal of a weather ship became a negative factor in forecasts leading up to the Great Storm of 1987. The last weather ship was Polarfront, known as weather station M ("Mike"), which was removed from operation on January 1, 2010. Weather observations from ships continue from a fleet of voluntary merchant vessels in routine commercial operation.

Function

The primary purpose of an ocean weather vessel was to take surface and upper air weather measurements, and report them via radio at the synoptic hours of 0000, 0600, 1200, and 1800 Universal Coordinated Time (UTC). Weather ships also reported observations from merchant vessels, which were reported by radio back to their country of origin using a code based on the 16-kilometer (9.9 mi) square in the ocean within which the ship was located. The vessels were involved in search and rescue operations involving aircraft and other ships. The vessels themselves had search radar and could activate a homing beacon to guide lost aircraft towards the ships' known locations. Each ship's homing beacon used a distinctly different frequency.[4] In addition, the ships provided a platform where scientific and oceanographic research could be conducted. The role of aircraft support gradually changed after 1975, as jet aircraft began using polar routes.[5] By 1982, the ocean weather vessel role had changed too, and the ships were used to support short range weather forecasting, in numerical weather prediction computer programs which forecast weather conditions several days ahead, for climatological studies, marine forecasting, and oceanography, as well as monitoring pollution out at sea. At the same time, the transmission of the weather data using Morse code was replaced by a system using telex-over-radio.

Origin

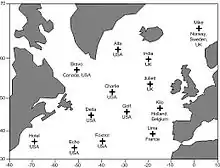

| Letter | Name | Latitude (North) |

Longitude (East) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Able/Alpha | 62° | −33°[5] |

| B | Baker/Bravo | 56° 30" | −51°[6] |

| C | Charlie | 52° 45" | −35° 30"[5] |

| D | Dog/Delta | 44° | −41°[7] |

| E | Easy/Echo | 35° | −48°[7] |

| F | Fox | 35° | −40°[7] |

| G | George | 46° | −29°[8] |

| H | Hotel | 38° | −71°[9] |

| I | India | 59° | −19°[5] |

| J | Juliet/Juliett | 52° 30" | −20°[5] |

| K | Kilo | 45° | −16°[9] |

| L | Lima | 57° | −20°[5] |

| M | Mike | 66° | 2°[5] |

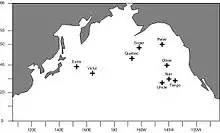

| N | Nan/November | 30° | −140°[10] |

| O | Oboe | 40° | −142°[10] |

| P | Peter/Papa | 50° | −145°[10] |

| Q | Quebec | 43° | −167°[11] |

| R | Romeo | 47° | −17°[5] |

| S | Sugar | 48° | −162°[6] |

| T | Tango | 29° | −135°[12] |

| U | Uncle | 27° 40" | −145°[13] |

| V | Victor | 34° | 164°[9] |

| X | Extra | 39° | 153°[14] |

In the 1860s, Britain began connecting coastal lightships with submarine telegraph cables so they could be used as weather stations. There were attempts to place weather ships using submarine cables far out into the Atlantic. The first of these was in 1870 with the old Corvette The Brick 50 miles off Lands End. £15,000 was spent on the project, but ultimately it failed. In 1881, there was a proposal for a weather ship in the mid-Atlantic, but it came to nothing. Deep-ocean weather ships had to await the commencement of radio telegraphy.[15]

The director of France's meteorological service, Météo-France, proposed the idea of a stationary weather ship in 1921 in order to aid shipping and the coming of transatlantic flights.[9] Another early proposal for weather ships occurred in connection with aviation in August 1927, when the aircraft designer Grover Loening stated that "weather stations along the ocean coupled with the development of the seaplane to have an equally long range, would result in regular ocean flights within ten years."[16] During 1936 and 1937, the British Meteorological Office (Met Office) installed a meteorologist aboard a North Atlantic cargo steamer to take special surface weather observations and release pilot balloons to measure the winds aloft at the synoptic hours of 0000, 0600, 1200, and 1800 UTC. In 1938 and 1939, France established a merchant ship as the first stationary weather ship, which took surface observations and launched radiosondes to measure weather conditions aloft.[5]

Starting in 1939, United States Coast Guard vessels were being used as weather ships to protect transatlantic air commerce, as a response to the crash of Pan American World Airways Hawaii Clipper during a transpacific flight in 1938.[2][9] The Atlantic Weather Observation Service was authorized by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on January 25, 1940.[17] The Germans began to use weather ships in the summer of 1940. However, three of their four ships had been sunk by November 23, which led to the use of fishing vessels for the German weather ship fleet. Their weather ships were out to sea for three to five weeks at a time and German weather observations were encrypted using Enigma machines.[18] By February 1941, five 327-foot (100 m) United States Coast Guard cutters were used in weather patrol, usually deployed for three weeks at a time, then sent back to port for ten days. As World War II continued, the cutters were needed for the war effort and by August 1942, six cargo vessels had replaced them. The ships were fitted with two deck guns, anti-aircraft guns, and depth charges, but lacked SONAR (Asdic), Radar, and HF/DF, which may have contributed to the loss of the USCGC Muskeget (WAG-48) with 121 aboard on September 9, 1942. In 1943, the United States Weather Bureau recognized their observations as "indispensable" during the war effort.[2]

The flying of fighter planes between North America, Greenland, and Iceland led to the deployment of two more weather ships in 1943 and 1944. Great Britain established one of their own 80 kilometres (50 mi) off their west coast. By May 1945, frigates were used across the Pacific for similar operations. Weather Bureau personnel stationed on weather ships were asked voluntarily to accept the assignment. In addition to surface weather observations, the weather ships would launch radiosondes and release pilot balloons, or PIBALs, to determine weather conditions aloft. However, after the war ended, the ships were withdrawn from service, which led to a loss of upper air weather observations over the oceans.[5] Due to its value, operations resumed after World War II as a result of an international agreement made in September 1946, which stated that no fewer than 13 ocean weather stations would be maintained by the Coast Guard, with five others maintained by Great Britain and two by Brazil.[2]

History of the fleet

Late 1940s

The establishment of weather ships proved to be so useful during World War II that the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) had established a global network of 13 weather ships by 1948, with seven operated by the United States, one operated jointly by the United States and Canada, two supplied by the United Kingdom, one maintained by France, one a joint venture by the Netherlands and Belgium, and one shared by the United Kingdom, Norway, and Sweden.[1] The United Kingdom used Royal Navy corvettes to operate their two stations, and staffed crews of 53 Met Office personnel. The ships were out at sea for 27 days, and in port for 15 days. Their first ship was deployed on July 31, 1947.[5]

During 1949, the Weather Bureau planned to increase the number of United States Coast Guard weather ships in the Atlantic from five at the beginning of the year to eight by its end.[19] Weather Bureau employees aboard the vessels worked 40 to 63 hours per week.[20] Weather ship G ("George") was dropped from the network on July 1, 1949, and Navy weather ship "Bird Dog" ceased operations on August 1, 1949.[8] In the Atlantic, weather vessel F ("Fox") was discontinued on September 3, 1949, and there was a change in location for ships D ("Dog") and E ("Easy") at the same time.[7] Navy weather ship J ("Jig") in the north-central Pacific Ocean was placed out of service on October 1, 1949.[21] The original international agreement for a 13 ship minimum was later amended downward. In 1949, the minimum number of weather ships operated by the United States was decreased to ten, and in 1954 the figure was lowered again to nine, both changes being made for economic reasons.[22] Weather vessel O ("Oboe") entered the Pacific portion of the network on December 19, 1949. Also in the Pacific, weather ship A ("Able") was renamed ship P ("Peter") and moved 200 miles (320 km) to the east-northeast in December 1949, while weather vessel F ("Fox") was renamed N ("Nan").[10]

1950s

Weather ship B ("Baker"), which had been jointly operated by Canada and the United States, became solely a United States venture on July 1, 1950. The Netherlands and the United States began to jointly operate weather ship A ("Able") in the Atlantic on July 22, 1950. The Korean War led to the discontinuing of weather vessel O ("Oboe") on July 31, 1950 in the Pacific, and ship S ("Sugar") was established on September 10, 1950.[6] Weather ship P's ("Peter") operations were taken over by Canada on December 1, 1950, which allowed the Coast Guard to begin operating station U ("Uncle") 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) west of northern Baja California on December 12, 1950. As a result of these changes, ship N ("Nan") was moved 400 kilometres (250 mi) to the southeast on December 10, 1950.[23]

Responsibility for weather ship V ("Victor") transferred from the United States Navy to the United States Coast Guard and Weather Bureau on September 30, 1951.[24] On March 20, 1952, Vessels N ("November") and U ("Uncle") were moved 32 to 48 kilometres (20 to 30 mi) to the south to lie under airplane paths between the western United States coast and Honolulu, Hawaii.[13] In 1956 USCGC Pontchartrain, while stationed at N ("November"), rescued the crew and passengers of Pan Am Flight 6 after the crippled aircraft diverted to the cutter's position and ditched in the ocean.[25] Weather vessel Q ("Quebec") began operation in the north-central Pacific on April 6, 1952,[11] while in the western Atlantic, the British corvettes used as weather ships were replaced by newer Castle-class frigates between 1958 and 1961.[5]

1960s

In 1963, the entire fleet won the Flight Safety Foundation award for their distinguished service to aviation.[5] In 1965, there were a total of 21 vessels in the weather ship network. Nine were from the United States, four from the United Kingdom, three from France, two from the Netherlands, two from Norway, and one from Canada. In addition to the routine hourly weather observations and upper air flights four times a day, two Soviet ships in the northern and central Pacific Ocean sent meteorological rockets up to a height of 80 kilometres (50 mi). For a time, there was a Dutch weather ship stationed in the Indian Ocean. The network left the Southern Hemisphere mainly uncovered.[22] South Africa maintained a weather ship near latitude 40° South, longitude 10° East between September 1969 and March 1974.[26]

Fading use

When compared to the cost of unmanned weather buoys, weather ships became expensive,[27] and weather buoys began to replace United States weather ships in the 1970s.[28] Across the northern Atlantic, the number of weather ships dwindled over the years. The original nine ships in the region had fallen to eight after ocean vessel C ("Charlie") was discontinued by the United States in December 1973.[29] In 1974, the Coast Guard announced plans to terminate all United States stations, and the last United States weather ship was replaced by a newly developed weather buoy in 1977.[9]

A new international agreement for ocean weather vessels was reached through the World Meteorological Organization in 1975, which eliminated Ships I (India) and J (Juliett), and left ships M ("Mike"), R ("Romeo"), C ("Charlie"), and L ("Lima") across the northern Atlantic, with the four remaining ships in operation through 1983.[30] Two of the British frigates were refurbished, as there was no funding available for new weather ships. Their other two ships were retired, as one of the British run stations was eliminated in the international agreement.[5] In July 1975, the Soviet Union began to maintain weather ship C ("Charlie"), which it would operate through the remainder of the 1970s and 1980s.[29] The last two British frigates were retired from ocean weather service by January 11, 1982, but the international agreement for weather ships was continued through 1985.[31]

Because of high operating costs and budget issues, weather ship R ("Romeo") was recalled from the Bay of Biscay before the deployment of a weather buoy for the region. This recall was blamed for the minimal warning given in advance of the Great Storm of 1987, when wind speeds of up to 149 km/h (93 mph) caused extensive damage to areas of southern England and northern France.[32] The last weather ship was Polarfront, known as weather station M ("Mike") at 66°N, 02°E, run by the Norwegian Meteorological Institute. Polarfront was withdrawn from operation on January 1, 2010.[33] Despite the loss of designated weather ships, weather observations from ships continue from a fleet of voluntary merchant vessels in routine commercial operation,[34] whose number has decreased since 1985.[35]

Use in research

Beginning in 1951, British ocean weather vessels began oceanographic research, such as monitoring plankton, casting of drift bottles, and sampling seawater. In July 1952, as part of a research project on birds by Cambridge University, twenty shearwaters were taken more than 161 kilometres (100 mi) offshore in British weather ships, before being released to see how quickly they would return to their nests, which were more than 720 kilometres (450 mi) away on Skokholm Island. 18 of the twenty returned, the first in just 36 hours. During 1954, British weather ocean vessels began to measure sea surface temperature gradients and monitored ocean waves.[5] In 1960, weather ships proved to be helpful in ship design through a series of recordings made on paper tape which evaluated wave height, pitch, and roll.[36] They were also useful in wind and wave studies, as they did not avoid weather systems like merchant ships tended to and were considered a valuable resource.[37]

In 1962, British weather vessels measured sea temperature and salinity values from the surface down to 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) as part of their duties.[5] Upper air soundings launched from weather ship E ("Echo") were of great utility in determining the cyclone phase of Hurricane Dorothy in 1966.[38] During 1971, British weather ships sampled the upper 500 metres (1,600 ft) of the ocean to investigate plankton distribution by depth. In 1972, the Joint Air-Sea Interaction Experiment (JASIN) utilized special observations from weather ships for their research.[5][39] More recently, in support of climate research, 20 years of data from the ocean vessel P ("Papa") was compared to nearby voluntary weather observations from mobile ships within the International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set to check for biases in mobile ship observations over that time frame.[40]

See also

Notes

- "Britain's First Weather Ship". Popular Mechanics. Vol. 89, no. 1. Hearst Magazines. January 1948. p. 136. ISSN 0032-4558.

- Malcolm Francis Willoughby (1980). The U.S. Coast Guard in World War II. Ayer Publishing. pp. 127–130. ISBN 978-0-405-13081-6.

- Mark Natola, ed. (2002). Boeing B-47 Stratojet. Schiffer Publishing Ltd. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-0764316708.

- Peter B. Schroeder (1967). Contact at Sea. The Gregg Press, Inc. p. 55.

- Captain C. R. Downes (1977). "History of the British Ocean Weather Ships" (PDF). The Marine Observer. XLVII: 179–186. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- United States Weather Bureau (October 1950). "Changes Made in Ocean Projects" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 9 (10): 132. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- United States Weather Bureau (October 1949). "Changes in Ocean Stations" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 8 (46): 489. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- United States Weather Bureau (August 1949). "Two Ocean Stations Dropped" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 8 (44): 457. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- Robertson P. Dinsmore (December 1996). "Alpha, Bravo, Charlie... Ocean Weather Ships 1940–1980". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Marine Operations. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- United States Weather Bureau (January 1950). "Changes Made in Pacific Stations" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 9 (1): 7. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- United States Weather Bureau (May 1952). "Station "Q" Established" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 11 (5): 79. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- Yaw-l Chu (March 1985). "Chapter 8: The Migration of Diamondback Moth" (PDF). Proceedings of the First International Workshop. The Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center: 79. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- United States Weather Bureau (April 1952). "Pacific Stations Relocated" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 11 (4): 48. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- Steven K. Esbensen and Richard W. Reynolds (April 1981). "Estimating Monthly Averaged Air-Sea Transfers of Heat and Momentum Using the Bulk Aerodynamic Method". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 11 (4): 460. Bibcode:1981JPO....11..457E. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1981)011<0457:EMAAST>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2060/19800020489.

- Kieve, Jeffrey L., The Electric Telegraph: A Social and Economic History, pp. 241-143, David and Charles, 1973 OCLC 655205099.

- George Lee Dowd Jr. (August 1927). "The First Plane to Germany". Popular Science. Vol. 111, no. 2. Popular Science Publishing Company, Inc. p. 121.

- United States Weather Bureau (April 1952). "Atlantic Weather Project". Weather Bureau Topics. 11 (4): 61.

- David Kahn (2001). Seizing the enigma: the race to break the German U-boat codes, 1939–1943. Barnes & Noble Publishing. pp. 149–152. ISBN 978-0-7607-0863-7.

- United States Weather Bureau (February 1949). "AWP Headquarters Moves to New York" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 8 (37): 353. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- United States Weather Bureau (October 1949). "Ocean Weather Duty" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 8 (46): 488. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- United States Weather Bureau (November 1949). "Navy Ocean Station Discontinued" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 8 (47): 503. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- Hans Ulrich Roll (1965). Physics of the marine atmosphere. Academic Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-12-593650-7.

- United States Weather Bureau (January 1951). "Changes in Pacific Ocean Station Program" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 10 (1): 12. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- United States Weather Bureau (August 1951). "Bureau to Operate Pacific Station "V"" (PDF). Weather Bureau Topics. 10 (8): 157. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- "16 October 1956". This Day in Aviation. Bryan R. Swopes. October 16, 2018.

- Ursula von St Ange (2002). "History of Ocean Wave Recording in South Africa". Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- J. F. Robin McIlveen (1998). Fundamentals of weather and climate. Psychology Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7487-4079-6.

- National Research Council (U.S.). Ocean Science Committee, National Research Council (U.S.). Study Panel on Ocean Atmosphere Interaction (1974). The role of the ocean in predicting climate: a report of workshops conducted by Study Panel on Ocean Atmosphere Interaction under the auspices of the Ocean Science of the Ocean Affairs Board, Commission on Natural Resources, National Research Council. National Academies. p. 40.

- Hans-Jörg Isemer (August 13, 1999). "Trends in Marine Surface Wind Speed: Ocean Weather Stations versus Voluntary Observing Ships" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 76. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- Pan-European Infrastructure for Ocean & Marine Data Management (September 11, 2010). "North Atlantic Ocean Weather Ship (OWS) Surface Meteorological Data (1945–1983)". British Oceanographic Data Centre. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- "Changes to the Manning of the North Atlantic Ocean Stations" (PDF). The Marine Observer. LII: 34. 1982. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 9, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- "Romeo Would Have Spied the Storm". New Scientist. Vol. 116, no. 1583. IPC Magazines. October 22, 1987. p. 22.

- Quirin Schiermeier (June 9, 2010). "Last Weather Ship Faces Closure". Nature News. 459 (7248): 759. doi:10.1038/459759a. PMID 19516306.

- National Data Buoy Center (2009-01-28). The WMO Voluntary Observing Ships (VOS) Scheme. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved on 2011-03-18.

- World Meteorological Organization (July 1, 2002). "The WMO Voluntary Observing Programme: An Enduring Partnership" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. p. 2. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- "What Makes a Good Seaboat?". New Scientist. Vol. 7, no. 184. The New Scientist. May 26, 1960. p. 1329.

- Stanislaw R. Massel (1996). Ocean surface waves: their physics and prediction. World Scientific. pp. 369–371. ISBN 978-981-02-2109-6.

- Carl. O. Erickson (March 1967). "Some Aspects of the Development of Hurricane Dorothy" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 95 (3): 121–130. Bibcode:1967MWRv...95..121E. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.395.1891. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1967)095<0121:SAOTDO>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

- Barry Saltzman (1985). Satellite oceanic remote sensing. Academic Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-12-018827-7.

- Hans von Storc and Francis W. Zwiers (2001). Statistical analysis in climate research. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-521-01230-0. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

References

- Adams, Michael R. (2010). Ocean Station: Operations of the U.S. Coast Guard, 1940–1977. Eastpoint, Maine: Nor'Easter Press. ISBN 978-0-9779200-1-3.