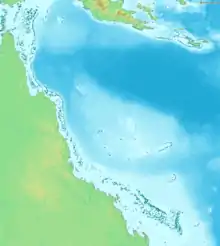

Ocean acidification in the Great Barrier Reef

Ocean acidification threatens the Great Barrier Reef by reducing the viability and strength of coral reefs. The Great Barrier Reef, considered one of the seven natural wonders of the world and a biodiversity hotspot, is located in Australia. Similar to other coral reefs, it is experiencing degradation due to ocean acidification. Ocean acidification results from a rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide, which is taken up by the ocean. This process can increase sea surface temperature, decrease aragonite, and lower the pH of the ocean. The more humanity consumes fossil fuels, the more the ocean absorbs released CO₂, furthering ocean acidification.

Calcifying organisms are under risk, due to the resulting lack of aragonite in the water and the decreasing pH. This occurs when ocean water combines with carbon dioxide to make carbonic acid and hydrogen ions, effectively acidifying the water. This process blocks many calcifying organisms from utilizing the carbonate ion in carbonic acid to make calcium carbonate (aragonite). Calcium carbonate is what the calcifying organisms use to make their shells and skeletons. Carbonate ions bond to the excess hydrogen ions in acidified waters, so the calcifying organisms slowly lose the ability to make their shells. The organisms work harder to rebuild their shells, which leads to loss of time for reproduction. Also, if too many hydrogen ions are in the water (indication of acidity), the ions will start to break apart the calcium carbonate molecules that make up the shells, essentially dissolving their shells.[1]

This decreased health of coral reefs, particularly the Great Barrier Reef, can result in reduced biodiversity. Organisms can become stressed due to ocean acidification and the disappearance of healthy coral reefs, such as the Great Barrier Reef, is a loss of habitat for several taxa.

Background

Atmospheric carbon dioxide has risen from 280 to 409 ppm[2] since the industrial revolution.[3] This increase in carbon dioxide has led to a 0.1 decrease in pH, and it could decrease by 0.5 by 2100.[4] When carbon dioxide meets seawater it forms carbonic acid, the molecules dissociate into hydrogen, bicarbonate, and carbonate and they lower the pH of the ocean.[5] Sea surface temperature, ocean acidity, and dissolved inorganic carbon are also positively correlated with atmospheric carbon dioxide.[6] Ocean acidification can cause hypercapnia and increase stress in marine organisms, thereby leading to decreasing biodiversity.[3] Coral reefs themselves can also be negatively affected by ocean acidification, as calcification rates decrease and acidity increases.[7]

Aragonite is impacted by the process of ocean acidification because it is a form of calcium carbonate.[5] It is essential in coral viability and health because it is found in coral skeletons and is more readily soluble than calcite.[5] Increasing carbon dioxide levels can reduce coral growth rates from 9 to 56% due to the lack of available carbonate ions needed for the calcification process.[7] Other calcifying organisms, such as bivalves and gastropods, experience negative effects due to ocean acidification as well. The excess hydrogen ions in the acidic water dissolve their shells, limiting their shelter and reproduction rates.[8]

As a biodiversity hotspot, the many taxa of the Great Barrier Reef are threatened by ocean acidification.[9] Rare and endemic species are in greater danger due to ocean acidification, because they rely upon the Great Barrier Reef more extensively. Additionally, the risk of coral reefs collapsing due to acidification poses a threat to biodiversity.[10] The stress of ocean acidification could also negatively affect other biological processes, such as reducing photosynthesis or reproduction and allowing organisms to become vulnerable to disease.[11]

Coral health

Calcification and aragonite

Coral is a calcifying organism, putting it at high risk for decay and slow growth rates as ocean acidification increases.[7] Aragonite assists the coral as they build their skeletons because it is another form of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) that is more soluble. When the pH of the water decreases, aragonite decreases as well, leading to the loss of calcium carbonate uptake in corals.[12] Levels of aragonite have decreased by 16% since industrialization and could be lower in some portions of the Great Barrier Reef due to the current, which allows northern corals to take up more aragonite than southern corals.[12] Aragonite is predicted to reduce by 0.1 by 2100 which could greatly hinder coral growth.[12] Since 1990, calcification rates of Porites, a common large reef-building coral in the Great Barrier Reef, have decreased by 14.2% annually.[7] Aragonite levels across the Great Barrier Reef itself are not equal; due to currents and circulation, some portions of the Great Barrier Reef can have half as much aragonite as others.[12] Levels of aragonite are also affected by calcification and production, which can vary from reef to reef.[12] If atmospheric carbon dioxide reaches 560 ppm, most ocean surface waters will be adversely undersaturated with respect to aragonite and the pH will have reduced by about 0.24 units – from almost 8.2 today to just over 7.9. At this point (sometime in the third quarter of this century at current rates of carbon dioxide increase) only a few parts of the Pacific will have levels of aragonite saturation adequate for coral growth. Additionally, if atmospheric carbon dioxide reaches 800 ppm, the ocean surface water pH decrease will be 0.4 units and total dissolved carbonate ion concentration will have decreased by at least 60%.[11] Recent estimates state that with business-as-usual emission levels, the atmospheric carbon dioxide could reach 800 ppm by the year 2100.[13] At this point, it is almost certain that all reefs of the world will be in erosional states. Increasing the pH and replicating pre-industrialization ocean chemistry conditions in the Great Barrier Reef, however, led to an increase in coral growth rates by 7%.[14]

Temperature

Ocean acidification can also lead to increased sea surface temperature. An increase of about 1 or 2 °C can cause the collapse of the relationship between coral and zooxanthellae, possibly leading to bleaching.[11] The average sea surface temperature in the Great Barrier Reef is predicted to increase between 1 and 3 °C by 2100.[4] Bleaching occurs when the zooxanthellae and coralline algae leave the coral skeleton behind due to stresses in the water. This causes the coral to lose its color because the previous organisms sustained on the coral skeleton vacate, leaving a white skeleton. The bleached coral can no longer complete photosynthesis, and so it slowly dies. The acidity of the water will slowly dissolve the leftover coral skeletons, essentially damaging the structural integrity of the coral reef. There are many organisms that also rely on the algae and zooxanthellae for their main source of food. Therefore, organisms in the bleached coral reef are forced to leave in search of new food sources. Since zooxanthellae and algae grow very slowly, restoring the coral reef to its original form will take a very long time.[15] This breakdown of the relationship between the coral and the zooxanthellae occurs when Photosystem II is damaged, either due to a reaction with the D1 protein or a lack of carbon dioxide fixation; these result in a lack of photosynthesis and can lead to bleaching.[5]

Reproduction

Ocean acidification threatens coral reproduction throughout almost all aspects of the process. Gametogenesis may be indirectly affected by coral bleaching. Additionally, the stress that acidification puts on coral can potentially harm the viability of the sperm released. Larvae can also be affected by this process; metabolism and settlement cues could be altered, changing the size of the population or viability of reproduction.[5] Other species of calcifying larvae have shown reduced growth rates under ocean acidification scenarios.[6] Biofilm, a bioindicator for oceanic conditions, underwent a reduced growth rate and altered composition in acidification, possibly affecting larval settlement on the biofilm itself.[16]

Health Reports of The Great Barrier Reef

Throughout the years there have been a few mass bleaching events that have affected the Great Barrier Reef. In particular, the years of 2016 and 2017, saw the reef sustain two years of back to back bleaching periods. This long period accounted for an estimated loss of half of the coral life in the Great Barrier Reef. The parts of the reef that did survive were damaged, leading to an overall period of low coral reproduction.[17] This was later followed by another bleaching event in 2020, making it the third bleaching event in five years. Studies found however that the results of the 2020 bleaching were not too severe, as it only affected a minimal amount of reefs, with most being in the lower to moderate levels of bleaching.[18]

In early 2022 a study showed, 91% of the many reefs that make the Great Barrier Reef, were experiencing some coral bleaching.[19] The reefs that had higher levels of bleaching, often were accompanied by higher overall air temperature. These temperature levels lasted all through the summer season in Australia, attributing to prolonged coral bleaching periods. Prolonged periods raise concern, as corals would not be able to reproduce and die out, leading to more loss of the reefs. However, recent reports from June 2022, have stated that the Great Barrier Reef, is currently recovering. Reefs affected by bleaching have lowered to 16% along different areas of the Australian Coast.[19] As ocean temperatures continue to drop, we can expect bleaching levels to go down, and coral levels to increase. Though coral bleaching has gone down, predators of the coral reef, Crown-of-thorns starfish, are still impacting coral growth and development.[19]

Biodiversity

The Great Barrier Reef is a biodiversity hotspot, ranging at over 5480 different species, including but not limited to species of coral, fish, sponges, sea snakes, marine turtles, mollusk, echinoderm, and marine alga.[20] However, the Great Barrier Reef is threatened by ocean acidification and its resulting increased temperature and reduced levels of aragonite. Elasmobranchs in the Great Barrier Reef are vulnerable to ocean acidification primarily due to their reliance on the habitat and ocean acidification's destruction of coral reefs. Rare and endemic species, such as the porcupine ray, are at high risk as well.[21] Larval health and settlement of both calcifying and non-calcifying organisms can be harmed by ocean acidification. A predator to coral reefs in the Great Barrier Reef, the Crown of Thorns sea star, has experienced a similar death rate to the coral on which it feeds. Any increase in nutrients, possibly from river run-off, can positively affect the Crown of Thorns and lead to further destruction of the coral.[6] Increasing temperature is also affecting the behavior and fitness of the common coral trout, a very important fish in sustaining the health of coral reefs.[22]

Coralline algae hold together some coral reefs and are present in multiple ecosystems. As ocean acidification intensifies, however, it will not respond well and could damage the viability and structural integrity of coral reefs. Ocean acidification can also indirectly affect any organism; increased stress can reduce photosynthesis and reproduction, or make organisms more vulnerable to disease. Additionally, as coral reefs decay, their symbiotic relationships and residents will have to adapt or find new habitats on which to rely.[11]

Organisms have been found to be more sensitive to the effects of ocean acidification in early, larval or planktonic stages. As ocean acidification does not exist without external factors, the multiple problems facing the Great Barrier Reef combine to further stress the organisms. Not only can ocean acidification affect habitat and development, but it can also affect how organisms view predators and conspecifics. Studies on the effects of ocean acidification have not been performed on long enough time scales to see if organisms can adapt to these conditions. However, ocean acidification is predicted to occur at a rate that evolution cannot match.[8]

Importance of Coral Reefs

Being a major hotspots of biodiversity, coral reefs are very important to the ecosystem and livelihood of marine and human life. Countries around the world depend on reefs as a source of food and income, especially for civilizations that inhabit small islands.[23] With over a 60% decrease in available fishing around coral reefs, many countries, will be forced to adapt.[24] Coral Reefs are also important for a countries economy, as reefs provide various forms of tourist activities, that can generate a lot of revenue for the economy. These can also contribute to individual levels of wellness, as the owners of these business, profit off of increased visitation and usage. Coral Reefs also provide, a form of costal infrastructure, that acts as a barrier between us a major ocean catastrophes, such as tsunamis and costal storms.[23]

References

- "Ocean Acidification | Smithsonian Ocean". ocean.si.edu. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii (NOAA)

- Widdecombe, S; Spicer, J. I. (2008). "Predicting the impact of ocean acidification on benthic biodiversity: what can animal physiology tell us?". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 366 (1): 187–197. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2008.07.024. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- Lough, Janice (2007). Climate and climate change on the Great Barrier Reef.

- Lloyd, Alicia Jane (2013). "Assessing the risk of ocean acidification for scleractinian corals on the Great Barrier Reef". Doctoral Dissertation: The University of Technology Sydney.

- Uthicke, S; Pecorino, D (2013). "Impacts of ocean acidification on early life-history stages and settlement of the coral-eating sea star Acanthaster planci". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e82938. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...882938U. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082938. PMC 3865153. PMID 24358240.

- De'ath, G; Lough, J. M. (2009). "Declining coral calcification on the Great Barrier Reef" (PDF). Science. 323 (5910): 116–9. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..116D. doi:10.1126/science.1165283. PMID 19119230. S2CID 206515977.

- Gattuso, Jean-Pierre (2011). Ocean acidification: Background and history.

- Fabricius, K. E.; De'ath, G (2001). Oceanographic Processes of Coral Reefs, Physical and Biological Links in the Great Barrier Reef (PDF). pp. 127–144.

- Chin, A; Kyne, P. M. (2010). "An integrated risk assessment for climate change: analyzing the vulnerability of sharks and rays on Australia's Great Barrier Reef". Global Change Biology. 16 (7): 1936–1953. Bibcode:2010GCBio..16.1936C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02128.x. S2CID 86718267.

- Veron, J. E. N.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O (2009). "The coral reef crisis: The critical importance of <350ppm CO2". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 58 (10): 1428–1436. Bibcode:2009MarPB..58.1428V. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.09.009. PMID 19782832.

- Mongin, M; Baird, M. E. (2016). "The exposure of the Great Barrier Reef to ocean acidification". Nature Communications. 7: 10732. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710732M. doi:10.1038/ncomms10732. PMC 4766391. PMID 26907171.

- FEELY, RICHARD A.; DONEY, SCOTT C.; COOLEY, SARAH R. (2009). "Ocean Acidification: Present Conditions and Future Changes in a High-CO₂ World". Oceanography. 22 (4): 36–47. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2009.95. hdl:1912/3180. ISSN 1042-8275. JSTOR 24861022.

- Tollefson, J (February 2016). "Landmark experiment confirms ocean acidification's toll on Great Barrier Reef". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19410. S2CID 130069543.

- "Coral Bleaching | AIMS". www.aims.gov.au. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- Witt, V; Wild, C (2011). "Effects of ocean acidification on microbial community composition of, and oxygen fluxes through, biofilms from the Great Barrier Reef". Environmental Microbiology. 13 (11): 2976–2989. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02571.x. PMID 21906222.

- Sommer, Lauren (26 March 2022). "Australia's Great Barrier Reef is hit with mass coral bleaching yet again". NPR. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- Emslie, Mike (2020–2021). "Long-Term Monitoring Program Annual Summary Report of Coral Reef Condition 2020/2021".

- "Reef health". www.gbrmpa.gov.au. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- Richards, Zoe T.; Day, Jon C. (8 May 2018). "Biodiversity of the Great Barrier Reef—how adequately is it protected?". PeerJ. 6: e4747. doi:10.7717/peerj.4747. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5947040. PMID 29761059.

- Fabricius, K. E.; De'ath, G (2001). Oceanographic Processes of Coral Reefs, Physical and Biological Links in the Great Barrier Reef. pp. 127–144.

- Johansen, J. L. (2014). "Increasing ocean temperatures reduce activity patterns of a large commercially important coral reef fish". Global Change Biology. 20 (4): 1067–1074. Bibcode:2014GCBio..20.1067J. doi:10.1111/gcb.12452. PMID 24277276. S2CID 32063100.

- US EPA, OW (30 January 2017). "Basic Information about Coral Reefs". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- Weisbrod, Katelyn (17 September 2021). "Big Reefs in Big Trouble: New Research Tracks a 50 Percent Decline in Living Coral Since the 1950s". Inside Climate News. Retrieved 23 August 2022.