Health in Turkey

The healthcare system in Türkiye has improved in terms of health status especially after implementing the Health Transformation Program (HP) in 2003.[1] “Health for All” was the slogan for this transformation, and HP aimed to provide and finance health care efficiently, effectively, and equitably. [2] By covering most of the population, the General Health Insurance Scheme is financed by employers, employees, and government contributions through the Social Security Institution. [1] Even though HP aimed to be equitable, after 18 years of implementation, there are still disparities between the regions in Türkiye. While the under-5 mortality rate in Western Marmara is 7,9, the under-5 mortality rate in Southeastern Asia is two times higher than Western Marmara, with the rate of 16,3 in 2021. [3]

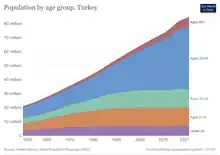

In 2022, the population of Türkiye calculated at more than 85 million by showing the trend in the population of old people increasing.[4] The causes of the changes between population pyramids in 2007 and 2022 are that the fertility rate decreased from 2,16 to 1,62 [4][5] and the life expectancy reached 78,3 years between 2018-2020 in Türkiye. [6]

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[7] finds that Turkey is fulfilling 81.6% of what it should be fulfilling for the right to health based on its level of income.[8] When looking at the right to health with respect to children, Turkey achieves 95.5% of what is expected based on its current income.[9] In regards to the right to health amongst the adult population, the country achieves only 92.0% of what is expected based on the nation's level of income. [10] Turkey falls into the "very bad" category when evaluating the right to reproductive health because the nation is fulfilling only 57.3% of what the nation is expected to achieve based on the resources (income) it has available.[11]

Turkish Health System

.jpg.webp)

Health services in Turkey are controlled by the Ministry of Health through a centralized state system. In 2003, the government introduced a comprehensive health reform program aimed at increasing the budget rate allocated to healthcare services and ensuring that a large part of the population is healthy. The Turkish Statistical Institute announced that it had spent 76.3 billion TL in health services in 2012; the Social Security Institution covered 79.6% of the service fees while the remaining 15.4% were paid directly by the patients."[12] According to 2013 figures, there are 30,116 health institutions in Turkey and per one doctor there are an average of 573 patients. In addition, the number of beds per 1000 people is 2.64.[13] Life expectancy in Turkey is 75.6 years for males and 81.3 years for females, and the life expectancy of the total population is 78.3 years. [6] The three most common causes of mortality in the country are cardiovascular diseases (35,4%), cancer (15,2%), respiratory diseases (13,5%).[14]

Healthcare in Turkey is majorly provided by Ministry of Health and some private health institutions. [15]

Primary Healthcare System

The Turkish Public Health Association is accountable for the primary healthcare delivery in Turkey.[15]

Services[16] that are managed, developed and supervised by the Public Health Association are (health related units):

Primary Health Care Services

- Supervising the Family Medicine Unit (which consists of a Family Physician and a health personnel) and General Practitioners

- Immigration Healthcare Services

Communicable Diseases Control Programmes

- Early warning-response field epidemiology unit

- Communicable Diseases Unit

- Preventable diseases -Vaccination Unit

- Vector-borne and Zoonotic Diseases Unit

- Tuberculosis Unit

- Microbiology Laboratories Unit

Non-communicable Diseases Programmes and Cancer

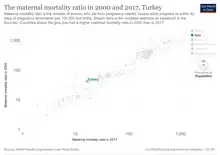

Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR)

According to the WHO data between the years 2000 to 2017, maternal mortality ratio in Türkiye has decreased from 42 to 17 in 17 years. [17] In 2010, Türkiye was nearly on par with some of the other OECD countries such as South Korea and Hungary and had a lower maternal mortality ratio than United States.[18]

| 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMR(Per 100,000 live births) | 42 | 33 | 24 | 19 | 17 |

Under-five Mortality Rate (U5MR)

Türkiye's U5MR in 2021 was reduced by 88% over 1990 levels, while in the rest of the world the total reduction was %59 between 1990 and 2021. [19] Even though Türkiye has accomplished to reduce U5MR, it has always been higher than the Europe and Central Asia averages between 1990 and 2021. [20]

| 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U5MR (per 1000 live births) | 74 | 54 | 38 | 26 | 18 | 13 | 9 |

Causes of Death

The top 5 causes of death are cardiovascular diseases (35,4%), cancer (15,2%), respiratory diseases (13,5%), endocrine and nutritional diseases (4,5%), and others (%13).[14] When the diseases causing death are examined on a gender basis; deaths from circulatory and endocrine diseases were found mostly in women and deaths from cancers and external causes were seen in men. [3]

| YEARS (%) | cardiovascular system diseases | benign and malignant tumors | respiratory system diseases | endocrine, nutrition and metabolism related diseases | COVID-19 | nervous system and sensory organs diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 33.5 | 14.0 | 13.4 | 4.2 | 11.5 | 3.3 |

| 2022 | 35.4 | 15.2 | 14.4 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 3.6 |

NCDs already account for over 89 percent of all mortality in Türkiye. [21]

Top ten causes of deaths in 2019 [21] from the most causes to the least are:

- Ischemic heart disease

- Stroke

- Lung cancer

- COPD

- Alzheimer's disease

- Diabetes

- Chronic kidney disease

- Hypertensive heart disease

- Lower respiratory infections

- Colorectal cancer

However, combining death causes with disability causes is changing the top ten list and, it includes low back pain, neonatal disorders, depressive disorders, headache disorders, and gynecological diseases.

The risk factors the drive most death and disability in Türkiye are tobacco use, high body-mass index and high blood pressure. [21] WHO estimates that 42% of men are tobacco smokers. [22]

"Multisectoral action plan of Türkiye for non-communicable diseases 2017–2025" [23] has been established by the Turkish Ministry of Health in order to halt and manage the NCDs in Türkiye. The action plan[23] is coordinated with the Sustainable Development Goals.

Obesity and Dietary Behaviors

One of the risk factors that causes death and disability is a high body-mass index, which increased the DALYs (per 100.000) +453.9 between 2009 and 2019 in Türkiye. The other risk factors that are on the top ten list, many of them related to eating behaviors.[24] Türkiye has the highest rate of obesity in the WHO European Region; according to the European Obesity Report 2022 by WHO, more than 65% of adults are overweight or obese in Türkiye. [25] Further, obesity in females (39.1%) is higher than in males (24.6%). [26]

The increased prevalence of obesity in Türkiye is attributed to the changes in dietary behaviors. Turkish people eat fewer grains, bread, vegetables, and fruits than before. This causes an increase in fat intake and energy percentage from fats and a decrease in vitamin C intake. Although the energy and macronutrient intakes are within the recommended ranges (carbonhydrates: 50%, protein: 15%, and fat: 35%),[26] it is seen that the diet of Turkish people has shifted to a Western-type diet in terms of micronutrients and food groups. [27]

Additionally, one of the determinants of obesity is urbanization in Türkiye due to sedentary lifestyle in the cities, availability of public transportation, working more at office jobs, and changes in social and economic structure. Migrating to big cities is popular and causes high unemployment rates, which might also cause less physical activity. [28][29] The other social determinants of obesity are being married and having a lower educational level in Türkiye. [30] A lack of knowledge about health and the health consequences contribute to the high percentage of excessive weight. [29]

Obesity and being overweight is higher among women for several reasons. A majority of women do not have jobs outside of the home and lead more sedentary lifestyles as a result. Housework is often the only source of physical activity for women, as there is no prior tradition of women participating in sports. [29]

"Türkiye Health Nutrition and Active Life Program (2014–2017)" is implemented by the Ministry of Health in Türkiye in order to prevent obesity and reduce obesity-related diseases (cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, some types of cancer, hypertension, and musculoskeletal diseases) by encouraging people to have adequate and balanced nutrition and regular physical activity habits. [31] In 2019, the Ministry of Health in Türkiye extended the program and introduced the "Adult and Childhood Obesity Prevention and Physical Activity Action Plan (2019-2023). One of the actions in the program addresses the decreased purchasing power problem in Türkiye by minimizing inflation on healthy products such as fish, milk, fruit, and vegetables and taking actions to increase purchasing power. [32]

In 2022 half of children ate fruit every day, and a third ate vegetables every day.[33] Placing fruit and vegetables outside shops attracts customers.[34] In 2022 a lawsuit was started claiming that the ban on vegan cheese was unconstitutional.[35]

Diabetes

.jpg.webp)

Diabetes causes 2% of total deaths in all ages in Turkey.[36] Furthermore many more Turks die from Diabetic Kidney disease, a complication of Diabetes and non-diabetic High blood sugar, and some say that the consequences of Diabetes could cause up to 20% of all deaths in Turkey.

In 2016 it was estimated that 13.2% of the population had diabetes and there is an increasing trend in the prevalence of diabetes.[36] The main cause of this could be the fact that over Nearly 2 in 3 Turks are overweight and that 1 in 3 are obese.

Diabetes has been described as “one of the top priorities” for the Turkish government.[37] An operational action plan for diabetes, overweight and obesity exists as a national response to the diabetes.[36]

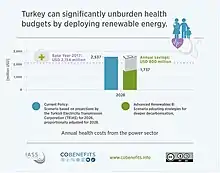

Air pollution and climate change

Air pollution in Turkey is estimated to be a cause of 8% of deaths in 2019.[38] Coal is a major contributor to air pollution, and damages health across the nation, being burnt even in homes and cities.[39] It is estimated that a phase out of coal power in Turkey by 2030 instead of by the 2050s would save over 100 thousand lives.[40] Climate change in Turkey may impact health, for example due to increased heatwaves.[41][42]

Vaccine-preventable Diseases

Vaccines that are on the existing immunization schedule of the government are free of charge.

According to the recent 'WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system' reported cases for Diphtheria were 0, Measles were 9, Rubella were 7, Mumps were 544 and Tetanus(total) were 16 cases in 2016.[43]

Immunization Schedule[43]

- HepB_pediatric : birth;1, 6 months

- BCG : 2 months

- DTaPHibIPV : 2,4,6,18 months

- Pneumo_conj : 2,4,6,12 months

- MMR :12 months, 6 years

- TdaPIPV : 6 years

- OPV : 6, 18 months

- Td : 14 years

- HepA_pediatric : 18,24 months

- Varicella : 12 months

- Influenza_Adult : >=65 years

- Influenza - Pediatric : 6 months

HIV/AIDS in Turkey

Between 2006 and 2017, new HIV infections increased by 465%.[44] AIDS is a disease that is not decreasing as in much of the rest of the world. Analysis of nearly 7000 cases reveal data about HIV in Turkey.[45] AIDS in Turkey is often described as a "Gay disease", "African disease", or "Natasha disease",[46] so people tend to hide their illness. "According to the United Nations HIV / AIDS Theme Group's 2002 HIV / AIDS Situation Analysis report in Turkey, between 7,000 and 14,000 people have been infected with AIDS since the beginning of the pandemic. Figures released by the (Ministry of Health) in June 2002 show that a total of 1,429 HIV / AIDS cases had been reported since 1985."[47] Due to problems in the registration and notification system, obtaining reliable numerical information about AIDS cases is very difficult in Turkey.[48]

"The disease is seen in 20-45 groups. It is estimated that approximately 2,000 people have been treated with this disease in Turkey. Marmara region where the most case report is made to the current. These are followed by Ankara, Izmir, Antalya, Mersin, Adana and Bursa respectively. Foreign nationals who make up about 16 percent of cases are from Ukraine, Moldova and Romania."[49]

2009 swine flu pandemic in Turkey

The 2009 flu pandemic was a global outbreak of a new strain of influenza A virus subtype H1N1, first identified in April 2009, termed Pandemic H1N1/09 virus by the World Health Organization (WHO)[50] and colloquially called swine flu. The outbreak was first observed in Mexico,[51] and quickly spread globally. On 11 June 2009, WHO declared the outbreak to be a pandemic.[52][53] The overwhelming majority of patients experience mild symptoms",[52] but some persons are in higher risk groups, such as those with asthma, diabetes,[54][55] obesity, heart disease, or who are pregnant or have a weakened immune system.[56] In the rare severe cases, around 3–5 days after symptoms manifest, the sufferer's condition declines quickly, often to the point respiratory failure.[57]

The virus reached Turkey in May 2009. A U.S. citizen, flying from the United States via Amsterdam was found to be suffering from the swine flu after arriving at Istanbul's Atatürk International Airport.[58] Turkey is the 17th country in Europe and the 36th country in the world to report an incident of swine flu.

The Turkish Government has taken measures at the international airports, using thermal imaging cameras to check passengers coming from international destinations.[59]

The first case of person to person transmission within Turkey was announced on 26 July 2009.

On 2 November, the Turkish Health Ministry began administering vaccines against H1N1 influenza, starting with health workers.[60]

After a slow start, the virus spread rapidly in Turkey and the number of cases reached 12,316.[61] First death confirmed on 24 October and death toll reached 627.[61]

COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey

.jpg.webp)

The COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey is part of the ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease was confirmed to have reached Turkey on 11 March 2020, after a man who had returned to Turkey from Europe, tested positive.[62] The first death due to COVID-19 in the country occurred on 15 March 2020 and by 1 April, it was confirmed that COVID-19 had spread all over Turkey.[63] On 14 April 2020, the head of the Turkish Ministry of Health Fahrettin Koca announced that the spread of the virus in Turkey has reached its peak in the fourth week and started to slow down.[64] The disease is exacerbated by air pollution,[65] for example from burning coal in Turkey for residential heating.[66]

As of 22 July 2020, the total number of confirmed cases in the country is over 222,400. Among these cases, 205,200 have recovered and 5,500 have died.[67] On 18 April 2020, the total number of positive test results surpassed that of Iran, making it the highest in the Middle East.[68][69] Turkey also surpassed China in confirmed total cases on 20 April 2020.[70] The rapid increase of the confirmed cases in Turkey did not overburden the public healthcare system,[71] and the preliminary case-fatality rate remained lower compared to many European countries.[72][73] Discussions mainly attributed these to the country's relatively young population and high number of available intensive care units.[74][75]

See also

- Health care in Turkey

- Smoking in Turkey

References

- Tatar, Mehtap; Mollahaliloğlu, Salih; Sahin, Bayram; Aydin, Sabahattin; Maresso, Anna; Hernández-Quevedo, Cristina (2011). "Turkey. Health system review". Health Systems in Transition. 13 (6): 1–186, xiii–xiv. ISSN 1817-6127. PMID 22455830.

- Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Health. Sağlıkta Dönüşüm Programı. 2003.

- Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Health General Directorate of Health Information Systems. The Ministry of Health of Türkiye Health Statistics Yearbook 2021. Ankara: Ministry of Health Publication; 2023. 274 p.

- "Adrese Dayalı Nüfus Kayıt Sistemi Sonuçları, 2022". February 6, 2023.

- "TÜİK Doğum İstatistikleri, 2022". May 5, 2023.

- "TÜİK Hayat Tabloları, 2018-2020". April 26, 2023.

- "Human Rights Measurement Initiative – The first global initiative to track the human rights performance of countries". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- "Turkey - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- "Turkey - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- "Turkey - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- "Turkey - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- Hürriyet. "Sağlığa 76,3 milyar lira harcandı". Hürriyet Sağlık. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Wayback Machine. "Number of medical institutions, total hospital beds and number of hospital beds per 1000 population, 1967-2014". İnternet Archive. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "TÜİK Kurumsal Ölüm ve Ölüm Nedeni İstatistikleri, 2022". data.tuik.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- Oecd (2014). OECD Reviews of Health Care Quality: Turkey 2014. OECD Reviews of Health Care Quality. doi:10.1787/9789264202054-en. ISBN 9789264202047.

- "Turkiye Halk Sagligi Kurumu organizasyon yapisi". Archived from the original on 2015-01-15.

- "Maternal mortality country profiles". www.who.int. 19 September 2019. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- "Gapminder Tools". www.gapminder.org.

- "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2015. Available from http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare (Accessed 14.09.2023).

- "NCDs | UN Interagency Task Force on NCDs supports Turkey drive forward action on noncommunicable diseases". WHO. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017.

- "Multisectoral Action Plan on Noncommunicable Diseases (2017–2025) (PDF). Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Health Publication Number : 1057. ISBN 978-975-590-646-1.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2015. Available from http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare (Accessed 14.09.2023).

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe (2022). WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. ISBN 978-92-890-5773-8.

- Türkiye Ministry of Health General Directorate of Public Health, Türkiye Nutrition and Health Research (Türkiye Beslenme ve Sağlık Araştırması (TBSA)). Ankara: Türkiye Ministry of Health General Directorate of Public Health, 2019 [cited 2023 Sep 16]. Available from: https://krtknadmn.karatekin.edu.tr/files/sbf/TBSA_RAPOR_KITAP_20.08.pdf

- Koçyiğit, Emine; Esgin, Özge; Köksal, Eda (2023-01-09). "Türkiye'nin Değişen Beslenme Örüntüsü". Beslenme ve Diyet Dergisi (in Turkish). 50 (3): 40–52. doi:10.33076/2022.BDD.1670. ISSN 1300-3089.

- Sağin, Abdüsselam; Karasaç, Fatih (2020-01-31). "Obezitenin Sosyo-Ekonomik Belirleyicileri: OECD Ülkeleri Analizi". OPUS International Journal of Society Researches (in Turkish). 15 (21): 183–200. doi:10.26466/opus.613617. ISSN 2528-9527.

- Satman, Ilhan; et al. (2002). "Population-Based Study of Diabetes and Risk Characteristics in Turkey Results of the Turkish Diabetes Epidemiology Study (TURDEP)". Diabetes Care. 25 (9): 1551–1556. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.9.1551. PMID 12196426. S2CID 30179012.

- İpek, Egemen (2019-10-25). "Türkiye'de Obezitenin Sosyoekonomik Belirleyicileri". Uluslararası İktisadi ve İdari İncelemeler Dergisi (in Turkish) (25): 57–70. doi:10.18092/ulikidince.536601. ISSN 1307-9832.

- "Türkiye HEALTHY NUTRITION AND ACTIVE LIFE PROGRAM (2014 - 2017)" (PDF).

- "ADULT AND CHILDHOOD OBESITY PREVENTION AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY ACTION PLAN 2019 – 2023" (PDF).

- "Only 12.7 pct of children consume meat every day: TÜİK - Türkiye News". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- Абдувохидов, Бахтиер (2022-12-23). "Lessons learned from Turkey's success in retail fruit and vegetable trade and recommendations for Uzbekistan and Tajikistan • EastFruit". EastFruit. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- Ettinger, Jill (2022-07-18). "Turkey's Vegan Cheese Ban Is Unconstitutional, Says Lawsuit - Green Queen". Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- "WHO-Diabetes Country Profiles 2016" (PDF).

- "Top 10: Which country has the highest rates of diabetes in Europe? The UK's position might surprise you…". Diabetes UK. 27 August 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Kara Rapor 2020: Hava Kirliliği ve Sağlık Etkileri [Black Report 2020: Air Pollution and Heath Effects] (Report) (in Turkish). Right to Clean Air Platform Turkey. August 2020.

- "Turkey failing to adopt international air quality standard values, groups say". Ahval. 30 March 2022.

Homes and businesses in many Turkish cities burn coal, including the cheap and highly polluting lignite, to produce energy for heating and other purposes.

- Curing Chronic Coal: The health benefits of a 2030 coal phase out in Turkey (Report). Health and Environment Alliance. 2022.

- Akademisi, Türkiye Bilimler (July 2020). The Report on Climate Change and Public Health in Turkey (Report). Turkish Academy of Sciences. ISBN 978-605-2249-50-5.

- "Health and climate change: country profile 2022: Turkey - Turkey | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- "WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system. 2017 global summary". apps.who.int.

- "Number of HIV patients in Turkey up fourfold in last 10 years - Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News.

- Medikal Akademi (9 December 2015). "Türkiye AIDS Raporu: 7 Hastadan Biri Ev Kadını, Hastaların Yarısı Tedavi Almıyor". Medikal Akademi. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- "Istanbul Journal; 'Natasha Syndrome' Brings On a Fever in Turkey". New York Times. 17 April 1993. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- UNICEFF Türkiye. "Evet Deyin: Kış 2003 AIDS'i Anlamak". UNICEFF Türkiye. Archived from the original on 27 May 2005. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- UNICEFF Türkiye. "Çocuklarımız için bir Fark Yaratalım: HIV/AIDS Bilinci". UNICEFF Türkiye. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- HABERTURK (11 June 2012). "iste-turkiyenin-aids-haritasi". HABERTURK. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "WHO International" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-12. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- Maria Zampaglione (April 29, 2009). "Press Release: A/H1N1 influenza like human illness in Mexico and the USA: OIE statement". World Organisation for Animal Health. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

- Chan, Dr. Margaret (2009-06-11). "World now at the start of 2009 influenza pandemic". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 22 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- "UK National Institute for Medical Research WHO World Influenza Centre: Emergence and spread of a new influenza A (H1N1) virus, 12 June 09". Archived from the original on 2009-09-26. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- "Diabetes and the Flu". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Diabetes Translation (14 October 2009). "CDC's Diabetes Program - News & Information - H1N1 Flu". CDC.gov. CDC. Archived from the original on 23 October 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- Hartocollis, Anemona (2009-05-27). "'Underlying conditions' may add to flu worries". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 7, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- "Clinical features of severe cases of pandemic influenza". Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2009-10-16. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- "First case of swine flu confirmed in Turkey". turkishny.com. 2009-05-16. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- "Alarmed by swine flu, Turkey takes immediate action". Todayszaman.com. 2009-04-28. Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- "Turkey starts vaccinations against killer swine flu". Todayszaman.com. 2 November 2009. Archived from the original on 19 November 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "Son durum: 12 bin 316 vaka, 458 ölüm" (in Turkish). ntvmsnbc. 2009-12-22. Archived from the original on 2013-04-18. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- "Turkey confirms first coronavirus patient, recently returned from Europe". Daily Sabah. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "Sağlık Bakanı Koca: Son 24 saatte 7 kişi hayatını kaybetti, 293 yeni vaka görüldü". Euronews. 23 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Sağlık Bakanı Koca: Türkiye'de 4. haftada vaka artış hızı düşüşe geçti". Anadolu Agency. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Science in 5 - Episode #9 - Air pollution & COVID-19". www.who.int. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- "CORONA VE KÖMÜR" (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- "Türkiye'deki Güncel Durum". Ministry of Health. 22 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "Turkey's coronavirus cases highest in Middle East: Live updates". Al Jazeera. 19 April 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Turkey's coronavirus cases overtake Iran, highest in Middle East". Reuters. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Turkey's Coronavirus Crisis Grows as Infections Exceed China's". Foreign Policy. 20 March 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Turkey's public health system faces coronavirus pandemic". DW News. 7 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Mortality Analyses". Johns Hopkins University. 9 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Hasell, Joe; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (10 May 2020). "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "The Battle Over the Numbers: Turkey's Low Case Fatality Rate". Institut Montaigne. 4 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Türkiye: Kişi başına düşen yoğun bakım yatağı 2012-2018 arasında yüzde 46 arttı; Avrupa'da durum ne?". Euronews. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

.jpg.webp)