Nuragic sanctuary of Santa Vittoria

The Nuragic sanctuary of Santa Vittoria is an archaeological site located in the municipality of Serri, Sardinia – Italy. The name refers to the Romanesque style church built over a place of Roman worship which rises at the westernmost tip of the site. The Santa Vittoria site was frequented starting from the first phase of the Nuragic civilization corresponding to Middle Bronze Age (1600-1300 BC). Subsequently, from the late Bronze Age to the early Iron Age (1100-900 / 800 BC), the place became one of the most important expressions of the Nuragic civilization[1] and today it constitutes the most important Nuragic complex so far excavated.[2]

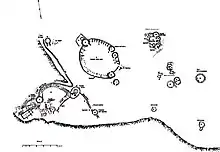

original plan of the Santa Vittoria site - Taramelli 1931 | |

| Location | Serri, Sardinia |

|---|---|

| Type | Sanctuary |

| Area | 3 ha |

| Height | 620 m |

| History | |

| Founded | Middle Bronze Age to early Iron Age |

| Periods | Bronze Age; Iron Age |

| Cultures | Nuragic civilization |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1909 to 1929 1990, 2011, 2015 |

| Archaeologists | Antonio Taramelli; Maria Gabriella Puddu |

| Public access | yes |

| Website | http://www.sardegnacultura.it/j/v/253?s=20781&v=2&c=2488&c1=2123&t=1 |

The presence of a significant layer of ash, found in the excavations, has led to the conclusion that in Roman times the site suffered a serious fire that devastated it completely.[3]

The various excavation campaigns, started in 1909 by Antonio Taramelli, extracted objects such as stylized nuraghes, bronze and stone bull protomes, votive weapons, fragments of lamps and numerous ex-voto mostly in bronze consisting of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines and models of everyday objects[1] as well as other important findings that testify the relationships the Nuragics had with the Etruria, Phoenicia and Cyprus.[4][3] The discovery of objects and coins of various mints highlight the continuity in use of the site in the subsequent Punic, Roman, Byzantine and medieval periods.[1][5]

Geography

The giara (plateau) of Serri has an altitude of over 600 metres (2,000 ft) above sea level, and is a basalt plateau, resting on the limestones of the surrounding plain, naturally defended by deep cliffs. The nuragic sanctuary of Santa Vittoria is located at the south west end of the giara itself, the more erect and less accessible part, while the opposite end has a less steep course. A megalithic support and defense wall was also built around the sanctuary.[6]

Description

The excavated area of the site has an extension of about 30,000 square metres (7.4 acres) but, as a whole, its original extension was 200,000 square metres (49 acres).[6] There are four groups of buildings built at different times:[7]

- the sacred area which includes:

- the corridor protonuraghe dating back to the Middle Bronze Age (1600-1300 BC);[1]

- the tholos nuraghe, which incorporated the pre-existing protonuraghe, dating back to the Recent Bronze Age (1300-1100 BC);[1]

- the well temple, the nearby "hypetral" (open air – without roof) temple, the sacred way; the two in antis temples, the first known as priest's hut and the other, located further north, known as chief's hut. All of them were built in the period between the final Bronze Age and the first Iron Age (1100 - 900/800 BC);[1][7]

- the small church of Santa Maria della Vittoria built in the Byzantine era.[8]

- the enclosure of the feasts (also enclosure of the meetings), coeval of the well temple, along whose inner perimeter are placed, facing the large internal area: a long porch, huts with benches and seats, the founders' hut, the market, three huts including that of the double-headed ax, the kitchen;[1]

- a group of buildings consisting of houses, including that of the double baetylus - from the name of the sacred artefact found there - belonging to the period between the final Bronze Age and the early Iron Age (1100 - 900/800 BC);[1]

- a fourth group of buildings, on the east side of the site, where the enclosure of tortures and the curia are located. They were built in the period between the final Bronze Age and the early Iron Age (1100 - 900/800 BC) [1]

The buildings were imaginatively named by archaeologists and can take on different names depending on the publication, which can be misleading. For example, the enclosure of the feasts is also called the enclosure of the meetings and the curia is named hut of the meetings. Therefore, to uniquely indicate the buildings, the number that was attributed to them by Taramelli in his general representation of the site is used. However, when his plan was published in 1931, due to the graphic format of the volume, a large empty portion of land between the enclosure of the feasts and the group of houses and the curia was eliminated. All plans published subsequently, and also the one exposed to visitors of the archaeological, site maintain the same error. Only the aerial photographs give its real size.[9]

The site

Protonuraghe and nuraghe

(Taramelli number 2 - 4)

Near the western edge of the site, close the church of Santa Vittoria, the remains of a nuragic tower are found. It was built with rows of basalt blocks and has an external diameter of about 7.5 metres (25 ft) with slits splayed inwards and dates to the recent Bronze Age (1300-1220 BC).

From the tower starts a corridor about 8 metres (26 ft) long and 1 metre (3.3 ft) high supported by two wings of jutting out basalt blocks that originally formed a covering. The corridor reaches the wall at the edge of the plateau.

The megalithic structures between the corridor and the wall have been attributed to a protonuraghe dated to the Middle Bronze Age (1500 - 1330 BC).[3]

On the ruins of this complex, a staircase of white limestone slabs was erected in Roman times which led to a small building, rectangular on the outside and almost circular inside, built in masonry with cocciopesto (Opus signinum) floor and tiled roof. Taramelli identified this building as the "aedes victoriae" or shrine of victory in memory of the Roman victory over the Sardinians and the destruction of the nuragic sanctuary. According to Taramelli this title gave the name to the church and then to the entire site.

Well temple

(Taramelli number 13)

The well temple is the most important place in the whole sanctuary, such as to be recognized first and immediately subject to excavation. The well temple was erected with isodomic masonry,[10] with regular rows of well-squared blocks of basalt and limestone that give a two-tone effect. It impressed Taramelli for its construction without mortar. It has a residual height of about 3 metres (9.8 ft) below ground level and about 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) above it and consists of a circular well of about 2 metres (6.6 ft) in diameter. The sacred water collects in a basin with a rounded bottom at the base of the well through special holes in the wall that allow rainwater to filter through. The wall is very regular and is made of twenty rows of black basalt stones, very well worked in the visible part and wedge-shaped in the part in contact with the rock well.

The staircase that descends to the basin is composed of 13 steps and has a slightly trapezoidal passage that narrows at 50 centimetres (20 in) at the base. The staircase ceiling is stepped.[11] The shape of the ruins suggests that the well had, like other sacred wells, an elevated tholos vault and that the two wings of the access hall, equipped with seats, could be covered with a double-pitched stone roof and a triangular tympanum similar to the Su Tempiesu at Orune, whose façade remains leaning against the rock. The vestibule of the temple is almost square in shape and is contained in the two lateral wings of the temple. The flooring is made of white limestone slabs coming from Isili (about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) away) perfectly interconnected without the use of binder.

Near the staircase there was a rectangular altar with a concavity equipped with a drain hole, which in turn gave onto a transverse channel which allowed the outflow of the liquids produced by the sacrifices without mixing them with the sacred waters of the well.

The temple is surrounded by a temenos, sacred enclosure, elliptical in shape, which had the function, as in other temples, to separate the temple from the rest of the site. The fence is built in megalithic work, that is with rough-hewn and not perfectly squared stones like those of the well.[3]

The practice of ordeal[11] and the treatment of infirmities (sanatio) in the Sardinian water sources, confirmed by the presence of many ex-votos, is mentioned by Gaius Julius Solinus who, in the 3rd century AD, reports that «springs, hot and wholesome, well up in many places. They offer a cure for broken bones, and for the dispelling of poison inserted by solifugae, and also for the curing of eye diseases. But what cures eyes is also powerful for discovering thieves. For whosoever denies a theft with an oath, and washes his eyes with these waters sees more clearly if he has not perjured himself. If a man falsely denies perfidy, his crime is revealed by blindness; captured by his eyes, he is driven to confess.»[12]

Hypetral temple

(Taramelli number 7)

It is a building of rectangular shape 5.80 by 4.80 metres (19.0 by 15.7 ft) oriented N-S with a structure of basalt blocks of squared isodome masonry and probable access from the south. The thickness of the walls is between 1.60 to 2 metres (5.2 to 6.6 ft). It was excavated in 1919-20.[3] It could have been a basin for ritual dives into the water that overflowed from the nearby well temple and flowed into it through a channel that was mistakenly eliminated during excavations.[13] The work is very damaged because its stones were largely used for the construction and restoration of the nearby church of Santa Vittoria during the Middle Ages and subsequently.[3] The fact that this building was a temple would be reflected in the presence of two altars, the first one being the larger (3.40 by 1.50 metres (11.2 by 4.9 ft)) which could be used for sacrifices of large animals, while the second one, smaller, would have been dedicated to the sacrifices of smaller animals. Next to the smaller altar there is a rectangular compartment perhaps used for the conservation of the ex-votos. Numerous bronze and silver artefacts were found inside the temple, including Nuragic bronze statuettes of animals and fragments of a two-wheeled chariot from the 9th-8th century BC.[3] Among the bronze statuettes, the "village chief" (today preserved in the Museo archeologico nazionale di Cagliari - National Archaeological Museum of Cagliari) deserves attention. It represents a male figure with his left hand raised in greeting and a long stick with a knob in the right hand. The face has an elongated nose and thick eyebrows. He wears a rounded cap and a cloak that wraps around his shoulders. The figure wears a V-neck tunic in front of which hangs a hilted dagger.[3]

Here were also found the probable remains of an Etruscan necklace consisting of elements of amber with a rectangular outline and an oval section, decorated with transverse ribs ascribed to the Final Bronze, around the beginning of the ninth century BC. Also of Etruscan origin were a double-foil silver disc adorned with studs, attributed to the period 700-675 BC and possibly a ciborium cover or a reproduction of a miniature shield, and several bronze sheet vases, reduced to fragments by the fire that devastated the site in Roman times.

Sacred way

With a length of about 50 metres (160 ft) the sacred way joins the well temple with the hypetral temple. In order to obtain a flat path, it is made in part by leveling the basaltic bottom of the plateau and in part paved with blocks placed on an embankment. It is between 3 and 4 metres (9.8 and 13.1 ft) wide.[3]

In antis temple priest's hut

(Taramelli number 8)

Located immediately south of the hypetral temple it is a circular construction with an external diameter of about 8 metres (26 ft) and a wall made of basalt blocks. Originally it had a conical roof, covered with straw and supported by wooden beams. The building has an entrance from the south which is preceded by a rectangular atrium (hence the name in antis: in the front) equipped with a seat on the west wing only. The excavations have brought to light a particular bronze statue representing a maimed figure who offers his hanger and which has been interpreted as an ex-voto.[3]

Group of the in antis temple chief's hut

(Taramelli numbers 32 and 33)

With respect to the sacred well, this group is located in the north and at a slightly higher position. It consists of three huts and the actual temple. The huts are interconnected with each other and are located southeast of the temple. Two of them are circular in shape while the third, obtained between the two previous ones, has a roughly quadrangular shape.

The temple, like the previous priest's hut, consists of a circular structure - with an external diameter of about 8.5 metres (28 ft) and a current height of about 3 metres (9.8 ft) preceded, towards the south, by a rectangular atrium, with a seat on each wing, placed in front of the splayed entrance of the circular chamber. The latter had beaten clay flooring, a tholos roof and 5 niches in the masonry. The atrium, with a paved pavement, probably had a pitched roof. The excavations have highlighted a significant presence in the Nuragic period revealed by pottery, bronze fragments of swords, rings, a bracelet and figurines. The presence continued in Roman times.[3][13]

Enclosure of the feasts

(Taramelli number 17)

The enclosure of the feasts, which Taramelli had called enclosure of the meetings, has an elliptical plan and overlooks a large square of about 40 by 50 metres (130 by 160 ft) on which the various buildings overlook: portico, market, huts and kitchen. This structure is thought to be the place where pilgrims celebrated the local deity, with festivities that lasted for some days and attracted people living nearby. It is thought that the most powerful clans of the Nuragic populations living in central Sardinia met in federal assemblies, to consecrate alliances or to decide wars. The common structures were arranged in such a way as to bring together the religious and the civil festivals, the market and the political assembly.

The archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu assumed that the enclosure of the feasts was the predecessor of one of those complexes called muristenes or cumbessias in Sardinian language, which host pilgrims gathered for the festivities. However, the hypothesis of a continuity in the use of the muristenes from the nuragic period to the present day has not yet found support by scholars, and in fact the Sardinian use of creating places of welcome for pilgrims near country churches would be either of Byzantine origin or linked to Benedictine monasticism, while muristenes are documented only from the 17th century. It could well be a custom linked to the period of the Counter-Reformation and similar to the Spanish romería, that is a pilgrimage during which markets and popular festivals are also hold.[8]

The enclosure has two entrances, the main one in the S-W and the secondary in the S-E. When entering from the main entrance, one comes across, clockwise, the eastern portico, the foundry, the market, the huts, and beyond the secondary entrance to the south, the kitchen, followed by the western portico.

Portico

(Taramelli numbers 25, 27, 29)

It is divided into two parts, the western one (number 25, to the right of the entrance for one who enters) of about 16 by 4 metres (52 by 13 ft) and the eastern one (numbers 27 and 29) of an approximately double length. It is formed by the perimeter wall of the enclosure and by pillars on the internal side. The perimeter wall has niches and a seat, while the pillars supported a wooden architrave and a wooden structure above which was placed a one pitch roof made of limestone slabs. Where the natural underlying rock is not present, the flooring is made of limestone slabs. The excavations found remains of meals eaten by gathered pilgrims, made up of «large quantities of animal bones, mostly ox, sheep and pork», a layer of debris from the roof,[14] and many household utensils.

Founders' hut

(Taramelli number 18)

It is a single-room building of about 7 metres (23 ft) of internal diameter with a basalt isodome structure. The excavation highlighted the presence of remains of stone slabs that presumably constituted the roof covering, originally supported by a wooden beam structure. A seat or bench runs all around the internal perimeter. Slag of copper and lead smelting and layers of ash were found here, which made Taramelli presume it was a foundry for the production of weapons and votive objects. Lilliu gives a different reading, assuming that it could have been a hut intended to host important people of the local clans.

Outside the founders' hut, outside the enclosure, there is a less-well-built stone structure that could have been an enclosure for animals (sheepfold).[3]

Market

(Taramelli number 31)

It consists of a series of nine cells with a rectangular plan closed by the external wall of the enclosure and by transverse walls. Each cell has a seat on three sides and is open towards the square. The market was equipped with a roof similar to the one of the portico. Two of the cells contain slabs used as counters for displaying goods.[3]

Three huts

(Taramelli number 19, 20, 21)

To the S-W of the market three huts are found, two with a circular plan and the third with a rectangular plan. Particular attention deserves the one towards the north, which is called the hut of the two-headed axe (Taramelli 19).

It has an entrance to the south, towards the square, with a diameter of about 6.5 metres (21 ft) and a perimeter wall of basalt about 1.3 metres (4.3 ft) thick. The roof was made of limestone slabs supported by a radial wooden structure. Along the entire internal perimeter is a stone step that acts as a seat. The floor is paved with limestone and basalt elements.

Inside there is an altar base above which a semi-spherical limestone cap was placed. At its feet it was found a double-headed bronze axe, 27 centimetres (11 in) in length. According to Taramelli this axe could constitute a sacred element to which animals were sacrificed, and indeed several bones were found on the spot (cattle, pigs, game and shellfish). A Punic coin from the mint of Sicily was also found in the hut, which attests its continuity of use to least until the 4th century BC, the date of minting.

An older pavement, made of limestone, was found under the more recent one. Nuragic artefacts were found in the layer between the two floors, among which was a double headed axe model which would attest to the origin of the ritual of the ax from the Nuragic period around the 7th century BC.[3]

Kitchen

(Taramelli number 24)

It consists of a large, almost square room with a side of about 6.5 metres (21 ft) with a large entrance facing N and access to the central square. Like other huts in the enclosure, it is supposed to have had a limestone slab roof supported by a wooden structure.

The wall opposite the door has a large niche preceded by three basalt blocks that would have formed the wings of the kitchen. The excavations have in fact found large remains of ashes and bones of domestic animals. Near the door there was a counter made up of two stone slabs that could have been used to cut portions of roasted meat.[3]

Enclosure of tortures

(Taramelli number 41)

It is a group of buildings consisting of a large and almost circular edifice divided into three rooms, one of which is also circular and to which two other external rooms are attached. It probably had a roof made of straw on wood beams.

The innermost circular compartment is the best built and has a basalt blocks masonry and an entrance with two basalt jambs.

Taramelli called this complex enclosure of tortures, assuming that the judgements carried out by the court in the nearby curia were executed in here. The contemporary interpretation is that of an important house that over time underwent a development from the inside out.[3]

Groups of housings

(Taramelli numbers 43 to 52)

They are located to the East of the enclosure of the feasts. The first group, further north, consists of a square around which various huts develop. Among them, the most significant is the one called the hut of the stele or hut of the double baetylus, composed of an almost circular space with a diameter of about 6 metres (20 ft) at the entrance of which two limestone slabs are placed. The floor is partly covered with limestone slabs where the natural basaltic bottom does not surface directly. A base at the bottom of the hut supported a "double baetylus" (now preserved in the National Archaeological Museum of Cagliari) which gives the building its name. It consists of a limestone cippus, about 1 metre (3.3 ft) high, made up of two small columns joined by a raised band representing a model of nuraghe used as an altar.[3] The second group contains two circular huts close together and connected by a wall.

Curia

(Taramelli number 35)

It is the building furthest from the sacred area and was among the first to be found by Taramelli in the first excavation campaign (1909-1910). It has a circular plan with an external diameter of 14 metres (46 ft) and an internal diameter of about 11 metres (36 ft). It is built with rows of basalt blocks and has an S-E-facing access with a stone threshold. The pavement is made of cobblestones which were originally covered by a layer of beaten black clay. Along the entire internal perimeter runs a seat made of limestone blocks about 35 centimetres (14 in) high which could hold about 50 people. At a height of about 3 metres (9.8 ft) ran a shelf made of white limestone slabs of which only a small number remains in place since most of them were used for the construction of tombs of the Roman era. The internal wall has five niches that would have contained ritual objects. At one of them the seat is interrupted to accommodate a stone basin, probably used to contain the ashes of the sacrifices. In front of it there was a baetylus about 0.5 metres (20 in) high in the shape of a truncated cone of limestone resting on a rectangular base. A trachyte basin was also found on the side of the door. The excavations brought to light bronze animal statuettes that would have represented the sacrificed animals and fragments of model ships with a bull horn bow. Common objects were also found: a dagger, a file, pins, vases in bronze foil of Etruscan origin, coins from Sicilian (4th century BC) and Sardinian mints (around 240 BC) and a cylindrical Cypriot torch holder decorated with three flower corollas (now preserved in the National Archaeological Museum of Cagliari) dating back to the end of the 8th century - first half of the 7th century BC.[3]

Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria

At the westernmost point of the nuragic complex stands the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria (Saint Mary of the Victory) which gives its name to the entire site. The primordial church was erected most likely in the Byzantine period during the military occupation of Sardinia. The church was probably rebuilt by the Benedictine Victor monks from the Abbey of St Victor, Marseille between the 8th and 9th centuries A.D.

The church had a Romanesque style with an original single nave plan, to which another nave was added, almost completely destroyed and rebuilt in recent years. It is still a local place of worship today.[3] To the side of the church are the remains of an ancient cemetery.[11] The festivities of Santa Vittoria occur on 11 September, a date linked to the renewal of agricultural and pastoral contracts in which a procession is held up to the church.[8]

Excavations

The site of Santa Vittoria was unknown until the beginning of the 20th century when the local doctor, who was a friend of the archaeologist Antonio Taramelli, then director of the Cagliari museum and of Sardinia's antiquity excavations, pointed out to him the Santa Vittoria site as worthy of interest.[15]

The first excavation was personally conducted in 1909-1910 by Taramelli with the collaboration of Filippo Nissardi, an archaeologist from Cagliari, and the inspector of the prehistoric and ethnographic museum of Rome Raffaele Pettazzoni. The first highlighted buildings were the city walls, the well temple and the meeting hut (or curia).

The campaign of 1919 - 1921 recovered significant votive bronzes.

In the campaign carried out between 1922 and 1929 discovered the in antis temple chief's hut and the enclosure of feasts fence, along with other buildings.

Taramelli began publications on Santa Vittoria in 1914 and concluded them in 1931 with two volumes published by the Accademia dei Lincei.[3]

It was during his first excavation campaign that Taramelli identified the Roman building which he named aedes victoriae (shrine of Victory) after which the church took its name and the site after it. This edifice was however demolished by Taramelli, as documented by him in 1931, to complete the exposure of the underlying nuragic layer.[9]

In 1963 Ercole Contu of the Superintendence for Antiquities of Sassari and Nuoro restored the enclosure of the feasts and the hypetral temple. This excavation recovered important nuragic ceramic artefacts and the remains of meals eaten in the enclosure, such as wild boar bones.[3]

Recent excavations were conducted in 1990, 2002 and 2006 by the Superintendence for antiquities,[15] in 2011[6] and in 2015 by Maria Gabriella Puddu.[2]

From 1 October 2019 the Superintendence of archeology, fine arts and landscape of Cagliari has started a new excavation campaign with consolidation and restoration works.[16]

The excavation campaigns recovered important objects which confirmed the relationships that the Nuragics had with the Etruscans, Phoenicians and Cypriots. It is worth mentioning a violin bow fibula in foliated bronze, a double silver foil disc, necklaces composed of amber and glass paste elements, vases in bronze foil of Etruscan origin and in particular a decorated cylindrical torch holder composed of three floral corollas of Phoenician origin from Cyprus dating from the late 8th - first half of the 7th century BC.[3] The torch holder and the bronze vases have been recovered in the so-called "curia".

Notes

- "Santuario nuragico di Santa Vittoria". Consorzio Turistico dei Laghi - Elmas (CA) - Italy. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- Canu, Nadia (2017). Santa Vittoria di Serri – Nell'Olimpia della Sardegna – Storia Archeologia Viva – anno XXXVI – n. 183 maggio – giungo 2017 – Giunti Milano

- Zucca, Raimondo (1988). Il santuario nuragico di Santa Vittoria di Serri in Sardegna Archeologica - Guide e Itinerari n. 7 - Carlo Delfino Editore – Sassari - Italia

- Tronchetti, Carlo (2016). Ancora su fenici, etruschi e Sardegna - Rivista di studi fenici - fondata da Sabatino moscati - XLIV-2016 – Roma - CNR editore - Edizioni Quasar

- Pilo, Chiara; Dore, Stefania (2019). Taramelli e l’archeologia romana e tardo-antica a Serri. Alla ricerca dei materiali - Atti delle giornate di studio "Antonio Taramelli e l’archeologia della Sardegna" a cura di Casagrande, Massimo; Picciau, Maura; Salis, Gianfranca - Abbasanta maggio 2019 - Soprintendenza archeologia belle arti e paesaggio per la città metropolitana di Cagliari e le province di Oristano e sud Sardegna; Soprintendenza archeologia belle arti e paesaggio per le province di Sassari e Nuoro

- Mancini, Paola (2011) Il santuario di Santa Vittoria di Serri. Campagna di scavo 2011 Fasti on line – Associazione di archeologia classica – Roma

- "Santuario di Santa Vittoria". SardegnaTurismo. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- Paglietti, Giacomo; et al. (2015). Il santuario di Santa Vittoria di Serri (Sardegna, Italia) Storia di un luogo di culto dall’età del Bronzo all’età medioevale - Revista Santuários, Cultura, Arte, Romarias, Peregrinações, Paisagens e Pessoas. belas-artes ulisboa- Lisboa, Portugal - ISSN 2183-3184

- Casagrande, Massimo (2015). Storia di una scoperta, le prime esplorazioni a Santa Vittoria di Serri in "Il Santuario di Santa Vittoria di Serri tra archeologia del passato e archeologia del futuro" a cura di Canu, Nadia; Cicilloni, Riccardo - Edizioni Quasar Roma 2015

- ashlars with hammered faces and drafted corners in rows having the same height

- Webster, Maud (2014). Water temples of Sardinia: identification, inventory and interpretation – Uppsala Universitet - Departmentof Archaeology and Ancient History - Master's Degree Thesis

- Gaius Iulius Solinus (III Century AD). De Mirabilibus Mundi chapters 4.6- 4.7 – in Gaius Iulius Solinus and his Polyhistor, (PhD diss., Macquarie University, 2011), Copyright Arwen Apps "Topos Text". Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation, Piraeus, Greece - developed by Pavla S.A. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Explanatory panel on site

- Taramelli, 1931 cited by Zucca, op. cit

- "Archeologia - Sito Istituzionale del Comune di Serri". Comune di Serri. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- "Santa Vittoria di Serri. Luce sul santuario nuragico". Archeologia Viva - Giunti Editore Spa. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

Bibliography

- Antonio Taramelli, Il tempio nuragico ed i monumenti primitivi di S. Vittoria di Serri (Cagliari), in Monumenti Antichi dei Lincei, XXIII, 1914, coll. 313-436, figg. 1-119, tavv. I-VIII;

- Antonio Taramelli., Nuove ricerche nel santuario nuragico di Santa Vittoria di Serri, in Monumenti Antichi dei Lincei, XXXIV, 1931, coll. 5-122, figg. 1-67, tavv. I-III;

- Giovanni Lilliu, La civiltà dei Sardi: dal Neolitico all'età dei nuraghi, Torino, ERI Rai, 1980, p. 240 ss., figg. 43-47, p. 320, fig. 66;

- Giovanni Lilliu, L'oltretomba e gli dei", in Nur: la misteriosa civiltà dei Sardi, edited by D. Sanna, Milano, Cariplo, 1980, p. 110 ss., 116 ss., figg. 91-93, p. 134;

- Ercole Contu, L'architettura nuragica, in Ichnussa. La Sardegna dalle origini all'età classica, Milano, Scheiwiller, 1981, pp. 99, 103 ss., tav, VII, b-c, p. 105 ss., pp. 115, 117, 122, 128 ss., figg. 121-124, 126-128, 141;

- Giovanni Lilliu, Serri. Loc. Santa Vittoria, in I Sardi: la Sardegna dal Paleolitico all'età romana, edited by E. Anati, Milano, Jaca Book, 1984, pp. 230–233;

- Raimondo Zucca, Il santuario nuragico di S. Vittoria di Serri, in Sardegna archeologica. Guide e Itinerari, Sassari, Carlo Delfino, 1988;

- Maria Gabriella Puddu, Recenti sondaggi di scavo a Santa Vittoria di Serri, in La Sardegna nel Mediterraneo tra il Bronzo medio ed il Bronzo recente (XVI-XIII sec. a.C.). Atti del III Convegno di Studi "Un millennio di relazioni fra la Sardegna ed i paesi del Mediterraneo"(Selargius-Cagliari, 27-30 novembre 1986), Cagliari, Amministrazione provinciale-Assessorato alla Cultura, 1987, pp. 145–156.