Nominal (linguistics)

In linguistics, the term nominal refers to a category used to group together nouns and adjectives based on shared properties. The motivation for nominal grouping is that in many languages nouns and adjectives share a number of morphological and syntactic properties. The systems used in such languages to show agreement can be classified broadly as gender systems, noun class systems or case marking, classifier systems, and mixed systems.[1] Typically an affix related to the noun appears attached to the other parts of speech within a sentence to create agreement. Such morphological agreement usually occurs in parts within the noun phrase, such as determiners and adjectives. Languages with overt nominal agreement vary in how and to what extent agreement is required.

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

History

The history of research on nominals dates back to European studies on Latin and Bantu in which agreement between nouns and adjectives according to the class of the noun can be seen overtly.

Latinate grammar tradition

Within the study of European languages, recognition of the nominal grouping is reflected in traditional grammar studies based on Latin, which has a highly productive marking system. Nominals can be seen in the shared morphemes that attach to the ends of nouns and adjectives and agree in case and gender. In the example below, 'son' and 'good' agree in nominative case because they are the subject of the sentence and at the same time they agree in gender because the ending is masculine. Likewise, 'the dog' and 'wild' share the same morphemes that show they agree in accusative case and masculine gender. In Latin agreement goes beyond nouns and adjectives.

| Explanation- The good son loves the wild dog. | |||||

| Latin: | fīlius | bonus | amat(1) | canem(2) (acc) | ferocem(3) (acc). |

| English: | [The] son | good | [he] loves | [the] dog | wild. |

Bantuist grammar tradition

The earliest study of noun classes was conducted in 1659 on Bantu languages,[2] and this study has to this day undergone only very minor modifications. These alterations began with Wilhelm Bleek's Ancient Bantu which led to Proto-Bantu.[2] The following example is from the Bantu language Ganda. For nominal classes in Bantu, see below.

| |||||

Theory of word-classes

Although much of the research on nominals focuses on their morphological and semantic properties, syntactically nominals can be considered a "super category" which subsumes noun heads and adjective heads. This explains why languages that take overt agreement features have agreement in adjectives and nouns.

Chomsky's analysis

In Chomsky's 1970 [±V, ±N] analysis, words with the feature "plus noun" that are not verbs "minus verb", are predicted to be nouns, while words with the feature "plus verb" and "minus noun" would be verbs. Following from this, when a word has both characteristics of nouns and verbs we get adjectives. When a word lacks either feature, one logically gets prepositions.[3]

| +V | –V | |

|---|---|---|

| +N | Adjectives | Nouns |

| –N | Verbs | Prepositions |

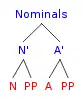

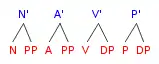

The following tree demonstrates that the category [+N] groups together nouns and adjectives.

This suggests English illustrates characteristics of nominals at a syntactic level because nouns and adjectives take the same complements at the head level. Likewise, verbs and prepositions take the same kinds of complements at the head level. This parallel distribution is predicted by the feature distribution of lexical items.

Cross-linguistic evidence

Slavic languages

In Russian, the nominal category contains nouns, pronouns, adjectives and numerals. These categories share features of case, gender, and number each of which are inflected with different suffixes. Nominals are seen as secondary inflection of agreement. Understanding the different noun classes and how they relate to gender and number is important because the agreement of adjectives will change depending on the type of noun. [4]

Example of nominal predicate:

'The girl is very beautiful' Девушка очень красив-а

Semantic noun class 1–5

Although there is not complete agreement about the categorization of noun classes in Russian, a common view breaks the noun classes up into five categories or classes, each of which gets different affixes depending on gender, case and number.

Noun class 1 refers to mass nouns, collective nouns, and abstract nouns.

examples: вода 'water', любовь 'love'

Noun class 2 refers to items with which the eye can focus on and must be non-active

examples: дом 'house', школа 'school'

Noun class 3 refers to non-humans that are active.

examples: рыба 'fish', чайка 'seagull'

Noun Class 4 refers to human beings that are not female.

examples: отец 'father, 'один' man

Noun Class 5 refers to human beings that are female.

examples: женщина "woman", мать 'mother'

Declensional noun class

Declensional class refers to the form rather than semantics.

| Declinational class 1 | Declinational class 2 | Indeclinational |

|---|---|---|

| Noun ending in -C | Noun ending in -a | Other |

| Masculine | Female | Neuter |

Morphological evidence

Nouns and adjectives inflect for case and gender.

In Russian, nominals occur when:

- Adjectives and non-personal pronouns take the same agreement as their referent

- Personal pronouns agree with the natural gender of the referent

Cases

- Nominative: expresses the subject

- Accusative: expresses the direct object

- Genitive: expresses possession; negative; and partitive

- Dative: expresses the indirect object

- Locative: expresses locational meaning

- Instrumental: expresses means [5]

Gender and class

Russian has three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. Gender and class are closely related in that the noun class will reflect the gender marking a nominal will get. Reflecting gender in Russian is usually restricted to the singular with a few exceptions in the plural. Gender is reflected on both the noun and the adjective or pronoun. Gendered nominals are clearly reflected in anaphors and relative pronouns because even if there is no explicit inflection upon the nouns they inherit animacy, gender and number from their antecedent.[4]

Affixes identifying one gender

| Number/Case | Affix | Gender |

|---|---|---|

| SG/NOM ACC | ∅ | Masc |

| SG/NOM ACC | -o | Neuter |

| SG INST | -ju | Fem |

| SG GEN | -u | Masc |

| SG LOC | ú | Masc |

| SG LOC | í | Fem |

| PL NOM | 'e | Masc |

Affixes linked with two genders

| Number/Case | Affix | Gender |

|---|---|---|

| SG/NOM ACC | ∅ | Masc, Fem |

| SG NOM | -a | Masc, Fem |

| SG ACC | -u | Masc, Fem |

| SG INT | -oj | Masc, Fem |

| SG GEN | -a | Masc, Neut |

| SG DAT | -u | Masc, Neut |

| SG INST | -om | Masc, Neut |

| PL NOM/ACC | -a | Masc, Neut |

Number

Russian has two numbers: singular and plural. Number is inherent to the noun so it is reflected by inflection on the noun and the agreeing nominals such as attributive adjectives, predicates and relative pronouns. There is only alteration of singular and plural between semantic classes 2–5 because class 1 does not distinguish between one or more than one.[4]

Adjectives

Adjectives agree with gender, case and number markings and consequently agree with the noun class.

Short form basic inflectional pattern

| Masc | Neut | Fem | PL |

|---|---|---|---|

| ∅ | -o | -a | -i |

Australian languages

Nominals are a common feature of Indigenous Australian languages, many of which do not categorically differentiate nouns from adjectives.

Some features of nominals in some Australian languages include:

- the ability to take grammatical case marking,

- the ability to function substantively (head a noun phrase), and

- the ability to function predicatively (modify another nominal).

Morphological evidence: Australian

- Mayali has four major noun class prefixes which attach to items within the nominal phrase: masculine, feminine, vegetable, and neuter.

An example paradigm is given below, adapted from .[6] One can see that each of the nominal morphemes in each class attaches to both the nouns and the adjectives.

| Type | Noun | Adjective | English |

| masculine | na-rangem | na-kimuk | 'big boy' |

| feminine | ngal-kohbanj | ngal-kimuk | 'big old-woman' |

| vegetable | man-mim | man-kimuk | 'big seed' |

| neuter | kun-warde | kun-kimuk | 'big rock' |

Bantu languages

Nominal structures are also found in Bantu languages. These languages constitute a sub-set of the Niger-Congo languages in Africa. There are approximately 250 different varieties of Bantu. Within these languages, nouns have historically been classified into certain groups based on shared characteristics. For example, noun class 1 and 2 represent humans and other animate objects, while noun class 11 represents long thing objects, and abstract nouns.[7]

Bantu languages use different combinations of the approximately 24 different Proto-Bantu noun classes.[2] The language with the highest number of documented noun classes is Ganda, which utilizes 21 of the 24 noun classes.[2] This ranges all the way to zero, which is the case in Komo D23, whose noun class system has faded out over time.[2] Languages that have approximately six classes paired for singular and plural and about six other classes that are not paired (e.g. infinitive and locative classes) are classified as canonical noun class systems, systems that have many noun classes.[2] These systems are far more typical of Bantu languages than the alternative, reduced noun class systems, such as Komo D23 and other languages that have limited noun classes.[2]

Morphological evidence: Bantu

A common feature of Bantu languages is nominal gender class agreement. This agreement can also be described as an extensive system of concord.[2] For every noun class, there is a corresponding gender class prefix. The nominal gender prefixes are shown below, with the "Proto-Bantu" (i.e. historical) prefixes on the left-hand side, and modern day Sesotho prefixes on the right-hand side. Note that modern day Sesotho has lost many noun classes.[7] This is typical of many other Bantu languages, as well.

| Proto-Bantu | Sesotho | Proto-Bantu | Sesotho |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: mo- | mo- | 12: ka- | |

| 1a: ø | ø | 13: to- | |

| 2: βa- | ba- | 14: βo- | bo- |

| 2a: β̀o- | bo- | 15: ko- | ho- |

| 3: mo- | mo- | 16: pa- | |

| 4: me- | me- | 17: ko- | ho- |

| 5: le- | le- | 18: mo- | |

| 6: ma- | ma- | 19: pi- | |

| 7: ke- | se- | 20: ɣo | |

| 8: βi-/di | di- | 21: ɣi | |

| 9: n- | (N)- | 22: ɣa | |

| 10: di-n- | di(N)- | 23: ɣe | |

| 11: lo- |

As can be seen in the table above, in the Sesotho variety of Bantu (spoken mainly in South Africa) there are approximately 15 nominal gender class prefixes. In this language, nouns and adjectives share the same gender class prefix. Adjectives take a 'pre'-prefix in addition to the main prefix. The main prefix (the one closest to the adjective, which is in bold in the example below) agrees with the prefix attached to the noun, whereas the 'pre'-prefix does not always agree with the noun.[7]

| ||||

The following examples from Swahili demonstrate class agreement with the noun, adjective and verb.[2] The different classes of the nouns in Swahili dictate which prefix will also agree with the adjective and verb.[2] It is not always the case in Bantu languages that the verb has noun agreement in the form of nominals, or in any form, but in Swahili it is a good representation of how these prefixes travel across the associated words.[2] In the first Swahili example, the noun has the prefix m- because it is part of class 1 for human beings. The prefix m- then agrees with the adjective m-dogo. The verb agreement is different simply because the verb agreement for class 1 is a- rather than m-. The second example has the prefix ki- because the noun basket is part of class 7. Class 7 has the same prefix form for nouns, adjectives and verbs.[2]

See also

References

Bibliography

- Acuña-Fariña, J. Carlos (2009). "'NP' doesn't say it all: The true diversity of nominal constituency types". Functions of Language. 16 (2): 265–281. doi:10.1075/fol.16.2.04acu. ISSN 0929-998X.

- Burton-Roberts, Noel; Poole, Geoffrey (2006). "'Virtual Conceptual Necessity', Feature-Dissociation and the Saussurian Legacy in Generative Grammar". Journal of Linguistics. 42 (3): 575–628. doi:10.1017/s0022226706004208. JSTOR 4177009. S2CID 171016939.

- Carter, Hazel (2009). "Negative structures in the syntactic tone-phrasing system of Kongo". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 37 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00094829. ISSN 0041-977X. S2CID 121426096.

- Cubberly, Paul (2002). Russian: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 114.

- Demuth, Katherine; Weschler, Sara (2012). "The acquisition of Sesotho nominal agreement". Morphology. 22 (1): 67–88. doi:10.1007/s11525-011-9192-7. ISSN 1871-5621. S2CID 123563367.

- Dixon (1982). Where have All the Adjectives Gone?: And Other Essays in Semantics and Syntax. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-082293-9.

- Harvey; Reid (1997). Nominal Classification in Aboriginal Australia. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-8193-7.

- Horie, Kaoru (2012). "The interactional origin of nominal predicate structure in Japanese: A comparative and historical pragmatic perspective". Journal of Pragmatics. 44 (5): 663–679. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2011.09.020. ISSN 0378-2166.

- Kapust, Waltraud H. (1998). Universality in noun classification. San Jose State University: UMI Dissertations Publishing. ISBN 9780591849653.

- Nurse, Derek; Philippson, Gérard, eds. (2003). The Bantu languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780700711345.

- Nørgård-Sørensen, Jens (2011). Russian Nominal Semantics and Morphology. Slavica Pub. ISBN 9780893573843.

- Seifart, Frank (2010). "Nominal Classification". Language and Linguistics Compass. 4 (8): 719–736. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2010.00194.x. ISSN 1749-818X.

- Van Eynde, Frank (2006). "NP-internal agreement and the structure of the noun phrase". Journal of Linguistics. 42 (1): 139–186. doi:10.1017/S0022226705003713. ISSN 0022-2267. S2CID 6070076.