Constitution of New Zealand

The constitution of New Zealand is the sum of laws and principles that determine the political governance of New Zealand. Unlike many other nations, New Zealand has no single constitutional document.[1][2] It is an uncodified constitution, sometimes referred to as an "unwritten constitution", although the New Zealand constitution is in fact an amalgamation of written and unwritten sources.[3][4] The Constitution Act 1986 has a central role,[5] alongside a collection of other statutes, orders in Council, letters patent, decisions of the courts, principles of the Treaty of Waitangi,[1][6] and unwritten traditions and conventions. There is no technical difference between ordinary statutes and law considered "constitutional law"; no law is accorded higher status.[7][8] In most cases the New Zealand Parliament can perform "constitutional reform" simply by passing acts of Parliament, and thus has the power to change or abolish elements of the constitution. There are some exceptions to this though – the Electoral Act 1993 requires certain provisions can only be amended following a referendum.[9]

|

|---|

|

|

After decades of self-governance, New Zealand gained full statutory independence from Britain in 1947. It is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democracy.[10][11] The monarch of New Zealand is the head of state – represented in the Realm of New Zealand by the governor-general – and is the source of executive, judicial and legislative power, although effective power is in the hands of ministers drawn from the democratically elected New Zealand House of Representatives.[11] This system is based on the "Westminster model", although that term is increasingly inapt given constitutional developments particular to New Zealand.[2] For instance, New Zealand introduced a unicameral system within a decade of its statutory independence.[12]

Sources of the constitution

The constitution includes, but is not limited to, the following sources:[3][13]

| Name | Date | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

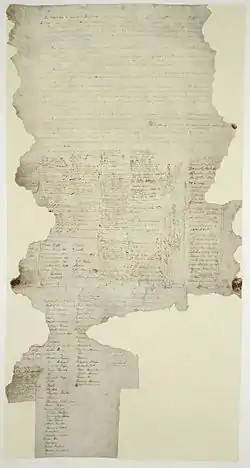

| Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi | 1840 | Conventions | The Treaty is an agreement that was made between Māori chiefs and representatives of the British Crown. It is New Zealand's "founding document".[14] References to the "principles of the Treaty of Waitangi" appear in a number of statutes.[15] |

| Cabinet Manual | 1979 | Conventions | Describes Cabinet procedures and is regarded as the "authoritative guide to decision-making for ministers and their staff, and for government departments."[16] |

| Official Information Act | 1982 | Statute | Provides for freedom of information and government transparency. |

| Letters Patent Constituting the Office of Governor-General of New Zealand | 1983 | Letters Patent | Describes the role of the governor-general and function of the Executive Council. |

| Constitution Act | 1986 | Statute | Describes the three branches of government. Replaced the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852. |

| Imperial Laws Application Act | 1988 | Statute | Incorporates important British constitutional statutes into New Zealand Law, including Magna Carta, the Bill of Rights 1689, and the Act of Settlement 1701. |

| New Zealand Bill of Rights Act | 1990 | Statute | Enumerates the rights of citizens against the state; enacts into law some of New Zealand's obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. |

| Electoral Act | 1993 | Statute | Describes the election of members of Parliament. |

| Senior Courts Act | 2016 | Statute | Describes the jurisdiction of the New Zealand Judiciary and constitutes New Zealand's senior courts including the Supreme Court of New Zealand as New Zealand's final court of appeal. |

Elements

The New Zealand constitution is uncodified and is to be found in formal legal documents, in decisions of the courts, and in practices (some of which are described as conventions).[17][18] It establishes that New Zealand is a constitutional monarchy, that it has a parliamentary system of government, and that it is a representative democracy.[11] It increasingly reflects the fact that the Treaty of Waitangi is regarded as a founding document of government in New Zealand.[19] The constitution must also be seen in its international context because New Zealand governmental institutions must increasingly have regard to international obligations and standards.

The Constitution Act 1986 describes the three branches of Government in New Zealand: The Executive (the Executive Council, as the Cabinet has no formal legal status), the legislature (the House of Representatives and Sovereign in Parliament) and the judiciary (Court system).[13]

Sovereign

.jpg.webp)

As per the Constitution Act 1986, New Zealand is a constitutional monarchy, wherein the role of the reigning sovereign is both legal and practical. The underlying principle is democracy, with political power exercised through a democratically elected parliament – this is often stated as "The [monarch] reigns but the government rules so long as it has the support of the House of Representatives."[13] Part 1 of the Constitution Act describes "The Sovereign", the reigning monarch, as New Zealand's head of state.[20]

Section 2(1) of the Act declares "The Sovereign in Right of New Zealand" as head of state,[20] and section 5(1) describes the sovereign's successor as being "determined in accordance with the enactment of the Parliament of England intituled The Act of Settlement".[20] This means that the head of state of the United Kingdom under the Act of Settlement 1701 is also the head of state of New Zealand. Under the Imperial Laws Application Act 1988, however, the Act of Settlement is deemed a New Zealand Act, which may be amended only by the New Zealand Parliament. "The Crown in right of New Zealand" has been legally divided from the British monarchy following New Zealand's adoption of the 1931 Statute of Westminster in 1947.[21]

"The Crown" is regarded as the embodiment of the state,[22] with the monarch at the centre of a construct in which the power of the whole is shared by multiple institutions of government acting under the sovereign's authority. The monarch is a component of Parliament, and the Royal Assent is required to allow for bills to become law.[23] In practice the monarch takes little direct part in the day-to-day functions of government; the decisions to exercise sovereign powers are delegated from the monarch, either by statute or by convention, to ministers of the Crown, or other public bodies, exclusive of the monarch personally. Moreover, as the monarch is not normally resident in the country, the sovereign's representative in and over the Realm of New Zealand is the governor-general.[20] The sovereign appoints the governor-general on the advice of the prime minister, who usually consults with the leader of the Opposition about the nomination. The office is largely ceremonial, although the governor-general holds a number of "reserve powers",[24] such as the ability to dismiss the prime minister in exceptional cases. Section 3(1) of the Constitution Act states "Every power conferred on the Governor-General by or under any Act is a royal power which is exercisable by the Governor-General on behalf of the Sovereign, and may accordingly be exercised either by the Sovereign in person or by the Governor-General".[20]

Government institutions

New Zealand's legislative, executive and judicial branches function in accordance with the Constitution Act 1986[20] and various unwritten conventions, which are derived from the Westminster system.

Although New Zealand doesn't have a single overarching constitutional document, we certainly have a constitution. There is a careful balance between our executive, legislature and judiciary. That classic separation of powers is a fundamental feature of a constitution, to provide checks and balances.

New Zealand has a legislature called the New Zealand Parliament, consisting of the King-in-Parliament and the House of Representatives. According to the principle of parliamentary sovereignty, Parliament may pass any legislation that it wishes.[26] Since 1996, New Zealand has used the mixed-member proportional (MMP) system, which is essentially proportional representation with single member seats (that can affect the proportionality of the House, but only to a limited degree). Seven electorates are currently reserved for members elected on a separate Māori roll. However, Māori may choose to vote in and to run for the non-reserved seats,[27] and several have entered Parliament in this way.

The Cabinet, which is responsible to Parliament, exercises executive authority. The Cabinet forms the practical expression of a formal body known as the Executive Council. The prime minister, as the parliamentary leader of the political party or coalition of parties holding or having the support of a majority of seats in the House of Representatives, chairs the Cabinet. Section 6(1) of the Constitution Act 1986 states, "A person may be appointed and may hold office as a member of the Executive Council or as a Minister of the Crown only if that person is a member of Parliament".[20] The prime minister and all other ministers take office upon receiving a warrant by the governor-general; this is based on the principle that all executive power ultimately stems from the sovereign. A government must be able to gain and maintain the support of a majority of the MPs in order to advise the governor-general and sovereign;[28] this is the principle of responsible government.

New Zealand's judiciary is a hierarchy consisting of the Supreme Court of New Zealand, the Court of Appeal of New Zealand, the High Court of New Zealand, and the District Courts. These courts are all of general jurisdiction. There are several other courts of specialist jurisdiction, including the Employment Court, the Environment Court and the Māori Land Court, as well as the Family Court and the Youth Court, which operate as specialised divisions of the District Courts. There are also a number of specialised tribunals which operate in a judicial or quasi-judicial capacity, such as the Disputes Tribunal, the Tenancy Tribunal and the Waitangi Tribunal.

Law

New Zealand law has three principal sources: English common law; certain statutes of the United Kingdom Parliament enacted before 1947 (notably the Bill of Rights 1689); and statutes of the New Zealand Parliament. In interpreting common law, there is a rebuttable presumption in support of uniformity with common law as interpreted in the United Kingdom and related jurisdictions. Non-uniformity arises where the New Zealand courts consider local conditions to warrant it or where the law has been codified by New Zealand statute.[29] The maintenance of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London as the final court of appeal and judges' practice of tending to follow British decisions, even though, technically, they are not bound by them, both bolstered this presumption. The Supreme Court of New Zealand, which was established by legislation in October 2003 and which replaced the Privy Council for future appeals, has continued to develop the presumption.

Judgment was delivered on 3 March 2015 in the last appeal from New Zealand to be heard by the Privy Council.[30][31][32]

Treaty of Waitangi

The place of the Treaty of Waitangi in the constitution is the subject of much debate.[6] The Treaty has no inherent legal status, but is treated in various statutes and is increasingly seen as an important source of constitutional law.[11][19]

The Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 put the text of the Treaty in statute for the first time (as a schedule) and created the Waitangi Tribunal to investigate claims relating to the application of the principles of the Treaty.[33] The Act was initially prospective but was amended in 1985 so that claims dating back to the signing of the Treaty in 1840 could be investigated.[34]

References to the "principles of the Treaty of Waitangi" appear in a number of statutes, although the principles themselves have not been defined in statute.[15] They are instead defined by a common law decision of the Court of Appeal from 1987, the famous "Lands case" brought by the New Zealand Māori Council (New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General)[35] over concerns about the transfer of assets from former government departments to state-owned enterprises, part of the restructuring of the New Zealand economy by the Fourth Labour Government. Because the state-owned enterprises were essentially private firms owned by the government, they would prevent assets that had been given by Māori for use by the state from being returned to Māori by the Waitangi Tribunal. The Māori Council sought enforcement of section 9 of the State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986: "Nothing in this act shall permit the Crown to act in a manner that is inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi."[36]

New Zealand Bill of Rights Act

The New Zealand Bill of Rights Act sets out the civil and political rights of New Zealand citizens against the three branches of government and entities and persons exercising public functions. The Act is not entrenched, and can, in theory, be amended by Parliament by a simple majority.[37]

History

Early history

Prior to European settlement of New Zealand, Māori society was based largely around tribal units with no national governing body. As contact with Europeans increased, there arose a need for a single governing entity. In 1788, the colony of New South Wales was founded. According to Governor Arthur Phillip's amended Commission dated 25 April 1787, the colony included "all the islands adjacent in the Pacific Ocean" and running westward on the continent to the 135th meridian east. Until 1840, this technically included New Zealand, but the New South Wales administration had little interest in New Zealand. Amid increasing lawlessness and dubious land transactions between Māori and Europeans, the British Colonial Office appointed James Busby as British Resident to New Zealand.

Busby convened the Confederation of Chiefs of the United Tribes of New Zealand, which adopted the Declaration of Independence of New Zealand at Waitangi in 1835. While the Declaration was acknowledged by King William IV, it did not provide a permanent solution to the issue of governance. In 1839 Letters Patent were created purported to extend the jurisdiction of the colony of New South Wales to New Zealand, in effect to annexe "any territory which is or may be acquired ... within that group of Islands known as New Zealand". This strategy was adopted by the Colonial Office in order to allow time for Captain William Hobson to legally acquire sovereignty from the United Tribes of New Zealand by treaty.

On 6 February 1840, the first copy of the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) was signed at Waitangi. Several subsequent copies were signed at various places around the North and South Islands. On 21 May Hobson issued two proclamations of British sovereignty over New Zealand, one for the North Island by Treaty,[38] and the other for the South Island by discovery (the South Island was declared "Terra nullius" or devoid of people.)[39] A further declaration on 23 May decried the "illegal assumption of authority" by the New Zealand Company settlements in Port Nicholson (Wellington and Britannia, later Petone) establishing their own 12-member governing council.[40] Hobson sought to prevent the establishment of what he saw as a 'republic', that is, an independent state outside of his jurisdiction.

In August 1840, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the New Zealand Government Act of 1840, allowing the establishment of a colonial administration in New Zealand separated from New South Wales.[41] Following this enactment, the Royal Charter of 1840 was declared. The Charter allowed for the establishment of the Legislative Council and Provincial Councils;[42] Hobson was then declared Lieutenant-Governor of New Zealand and divided the colony into two provinces (North Island—New Ulster, South Island—New Munster), named after the Northern and Southern Irish provinces.

On 3 May 1841, New Zealand was established as a Crown colony in its own right, with Hobson declared Governor.[43]

Self-government

The Imperial Parliament (Westminster) passed the first New Zealand Constitution Act 1846 empowering the government in New Zealand in 1846. The Act was to be fully implemented in 1848, but was never put in place because the governor-in-chief at the time, Sir George Grey, declined to apply it for a number of reasons. Instead, the Act was suspended for five years. Grey ruled with the powers of a dictator for the next five years; appointing Provincial councils at his pleasure.

Following the suspension of the 1846 Act, the Imperial Parliament moved again to grant New Zealand self-government with the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852, which repealed the earlier Constitution Act. This Act was based almost entirely on a draft by Sir George Grey, the main difference being the appointment of the Governor by the Secretary of the Colonies, and not by the (New Zealand) House of Representatives. The new Act did not take effect in New Zealand until 1853.

The Act provided:

- That New Zealand is divided into six provinces. Each province had an elected Superintendent, and the power to pass subordinate legislation (Ordinances). The Governor retained the right to veto legislation, and the Crown also had a right of disallowance within two years of the Acts passage;

- A General Assembly comprising the elected House of Representatives, appointed Legislative Council (upper house) and the governor was constituted to pass law for the "peace, order and good government of New Zealand";

- An Executive Council consisting all ministers, presided over by the governor.

The first enactment of the first Parliament of New Zealand elected under this Act was the English Acts Act of 1854,[44] which affirmed the application of 17 English statutes to New Zealand. This was expanded by the English Laws Act of 1858, which extended it to all English statutes in existence as at 14 January 1840;[45] specifically the Bill of Rights 1689, and Habeas Corpus. The powers of the New Zealand Parliament were clarified by the Colonial Laws Validity Act (Imperial) of 1865, which allowed a measured amount of legal independence. Under the Act, the New Zealand Parliament could pass laws inconsistent with British statutes or the common law, so long as the Imperial statute was not specifically applicable to New Zealand. Where this occurred, the New Zealand statute would be void.

In 1857 the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the New Zealand Constitution Amendment Act 1857, which allowed the New Zealand Parliament the ability to amend certain parts of the 1852 Act. This mainly related to proposals for new provinces in New Zealand. Several new provinces were then created by the New Zealand Parliament. The first major repeal of part of the Act came in 1876 with the Abolition of Provinces Act, which repealed section 2 of the Act and abolished the Provinces from 1 January 1877, thus centralising New Zealand's government in its bicameral Parliament.

In 1891 the composition of Legislative Council was changed, Councillors were no longer appointed for life; instead for terms of seven years with provision for reappointment.

Dominion and Realm

The Imperial Conference of 1907 resolved to allow certain colonies to become independent states, termed 'Dominions'. Following the Conference, the House of Representatives passed a motion requesting that King Edward VII "take such steps as he may consider necessary; to change New Zealand's official name from 'The Colony of New Zealand' to 'The Dominion of New Zealand'. Prime Minister Sir Joseph Ward prompted to move to "raise up New Zealand" and assured that it would "have no other effect than that of doing the country good". On 9 September, a Royal Proclamation granting New Zealand Dominion status was issued by King Edward VII. The proclamation took effect on 27 September. As a result, the office of governor became governor-general under the Letters Patent 1917 to reflect New Zealand's status as a dominion more fully. The Letters Patent also removed a number of powers the governor previously held while New Zealand was a colony.[46]

In 1908, two enactments of constitutional importance were passed: the Judicature Act, which describes the Jurisdiction of the New Zealand Judiciary; and the Legislature Act, setting out the powers of Parliament. The latter is now largely repealed, with only certain provisions that codify aspects of parliamentary privilege remaining.

The Imperial Conference of 1926 affirmed the Balfour Declaration of 1926, which stated Britain's Dominions were "equal in status". In respect of the governor-general, the Declaration stated that they held: "the same position in relation to the administration of public affairs in the Dominion" as was held by the monarch in the United Kingdom. The governor-general was thus bound by the advice of their responsible ministers.[47]

To give effect to the 1926 conference declarations, the Statute of Westminster 1931 was passed thus lifting the restrictions created by the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865. The Statute applied to New Zealand but would have to be adopted by the New Zealand Parliament as its own law to have application in New Zealand.[48] After much debate, this occurred in 1947 with the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act. At the request of the New Zealand Parliament, Westminster passed the New Zealand Constitution (Amendment) Act 1947 to grant the New Zealand Parliament full sovereign powers to amend or repeal the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852. The Parliament of the United Kingdom could still pass laws at the request of the New Zealand Parliament. This residual power, which was used only for the 1947 Amendment Act, was abolished with the passing of the Constitution Act 1986, which repealed the 1852 Constitution Act.[49]

As a result of these changes, New Zealand became a "Realm", with a legally separate Crown. It was not until the 1983 Letters Patent, the first amendment of the Letters Patent since 1917, that New Zealand was described as the Realm of New Zealand, which includes the self-governing territories of the Cook Islands and Niue.

Upper house

The National Party won the 1949 election promising to abolish the Legislative Council. The council was then stacked with the so-nicknamed "suicide squad" to allow the passage of the Legislative Council Abolition Act 1950 by the House of Representatives to abolish the upper house.[50] Despite proposals to re-establish an upper house, such as Jim Bolger's Senate proposal in 1990,[51] New Zealand's Parliament remains unicameral. As such, legislation is able to progress through the legislative stages much faster in comparison to other Westminster-style parliament. Legal academic and politician Geoffrey Palmer described the New Zealand Parliament in 1979 as the "fastest law maker in the West".[52]

Reforms of the 1984–1990 Labour Government

Immediately following the 1984 election in which the Labour Party gained a parliamentary majority, a constitutional crisis arose when incumbent Prime Minister Sir Robert Muldoon of the National Party refused to implement the instructions of Prime Minister-elect David Lange to devalue the New Zealand dollar to head off a speculative run on the currency.[53] The crisis was resolved when Muldoon relented three days later, under pressure from his own Cabinet, which threatened to install Deputy Prime Minister Jim McLay in his place.

Following the constitutional crisis, the incoming Fourth Labour Government formed an Officials Committee on Constitutional Reform to review the transfer of power. As a result of the committee, the Government released the Bill of Rights White paper and also introduced the Constitution Act 1986, the first major review of the New Zealand Constitution Act for 134 years.[54] Prior to this Act, only 12 of the 82 provisions of the 1852 Act remained in place. The Act consists of five main parts, covering the sovereign, the executive, the legislature, the judiciary, and miscellaneous provisions. Parliament also passed the Imperial Laws Application Act 1988 to clarify which Imperial and English Acts are to apply to New Zealand.

The Fourth Labour government also began the process of electoral reform. It convened the Royal Commission on the Electoral System in 1986. The Commission suggested New Zealand change to the mixed-member proportional (MMP) electoral system. Two referendums were held during the 1990s on the issue, with MMP being adopted in 1993 and implemented in 1996. Although MMP has resulted in many changes to New Zealand's political system, such as more complex governing arrangements negotiated between multiple parties, significant aspects of New Zealand's constitution remained the same following its adoption. For example, a proposal to create a supreme bill of rights that would grant courts the ability to invalidate Acts of Parliament via judicial review was rejected.[55] Parliament still functions as the supreme lawmaker.

The last major constitutional reform of the Fourth Labour Government was the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 (NZBORA).[56] The NZBORA puts New Zealand's commitment to the 1977 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) into effect in New Zealand law. However, the Act is neither entrenched nor supreme law (as was mooted in the White Paper of 1985)[57] and can, therefore, be repealed by a simple majority of Parliament.[58][55]

Reform

Because it is not supreme law, New Zealand's constitution is in theory comparatively easy to reform, requiring only a majority of members of Parliament to amend it,[59] as illustrated by the abolition of the Legislative Council in 1950.[50]

Certain aspects of the constitution are entrenched, after a fashion.[28] Section 268 of the Electoral Act declares that the law governing the maximum term of Parliament (itself part of the Constitution Act), along with certain provisions of the Electoral Act relating to the redistribution of electoral boundaries, the voting age, and the secret ballot, may only be altered either by three-quarters of the entire membership of the House of Representatives, or by a majority of valid votes in a popular referendum. Section 268 itself is not protected by this provision, so a government could legally repeal Section 268 and go on to alter the entrenched portions of law, both with a mere simple majority in Parliament. However, the entrenchment provision has enjoyed longstanding bipartisan support, and the electoral consequences of using a legal loophole to alter an entrenched provision would likely be severe.

Even though it is not legislatively entrenched, a material change to other aspects of the constitution is unlikely to occur absent broad-based support, either through broad legislative agreement or by referendum.

Referendums

There is no requirement for a referendum to enact constitutional change in New Zealand, except for the electoral system and term of parliament.[60] However, there have been several referendums in New Zealand's history, most recently to decide the nature of electoral reform in New Zealand. Many groups advocate constitutional reform by referendum, for example New Zealand Republic supports a referendum on a republic. The Privy Council as New Zealand's highest court of appeal was replaced by the Supreme Court of New Zealand by a simple Act of Parliament despite calls from New Zealand First, National and ACT for a referendum to be called on the issue.

The Citizens Initiated Referenda Act 1993 allows for non-binding referendums on any issue should proponents submit a petition to Parliament signed by 10% of registered electors. In 1999 one such referendum was held, on the question of whether the number of members of Parliament should be reduced from 120 to 99. Electors overwhelmingly voted in favour of the proposal. However, there were no moves to amend the Electoral Act 1993 in line with this result until 2006 when a bill was introduced by New Zealand First MP Barbara Stewart to reduce the size of Parliament to 100. The bill passed its first reading by 61 votes to 60 but was voted down at its second reading after it was recommended by Select Committee that the bill be dropped.

Referendums on constitutional issues in New Zealand (outcome in bold):[61]

| Year | Issue | Turnout[62] | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | Term of Parliament | 69.7% | 3 years: 68.1%, 4 years: 31.9% |

| 1990 | Term of Parliament | 85.2% | 3 years: 69.3%, 4 years: 30.7% |

| 1992 | Change of electoral system | 55.2% | Change: 84.7%, Keep 15.3% MMP: 70.3%, SM: 5.5%, STV: 17.5%, AV: 6.6% |

| 1993 | New electoral system | 85.2% | MMP: 54%, FPP: 46% |

| 1999 | Number of Members of Parliament | 81% | 99 MPs: 81.46%, 120 MPs: 18.53% |

| 2011 | Change of electoral system | 74.2% | Keep: 57.8%, Change 42.2% FPP: 46.7%, SM: 24.1%, STV: 16.3%, PV: 12.5% |

Proposals for reform

Written constitution

A poll by TVNZ in 2004 found 82% of those surveyed thought New Zealand should have a "written constitution".[63] In 2016, former Prime Minister Geoffrey Palmer and Andrew Butler created a "Constitution for Aotearoa New Zealand" to spark public discussion on a written constitution.[64]

Constitutional Arrangements Committee

In November 2004, the Prime Minister Helen Clark announced the formation of a select committee of the House of Representatives to conduct an Inquiry into New Zealand's existing constitutional arrangements. Both the National Party and New Zealand First did not participate.[65] Beginning in 2005, the Constitutional Arrangements Committee's Inquiry was conducted under five terms of reference, identifying and describing:

- New Zealand's constitutional development since 1840;

- the key elements in New Zealand's constitutional structure, and the relationships between those elements;

- the sources of New Zealand's constitution;

- the process other countries have followed in undertaking a range of constitutional reforms; and

- the processes which it would be appropriate for New Zealand to follow if significant constitutional reforms were considered in the future.

The committee made three key recommendations to the government:

- That generic principles should underpin all discussions of constitutional change in the absence of any prescribed process,

- That increased effort be made to improve civics and citizenship educations in schools, and

- That the government consider whether an independent institute could foster better public understanding of, and informed debate on, New Zealand's constitutional arrangements.

On 2 February 2006, the Government responded to the report of the committee. The Government responded favourably to the first and second recommendations, but did not support the third recommendation.[66]

Constitutional Review

In December 2010, a Constitutional Review was announced as part of the confidence and supply agreement between the National Party and the Māori Party, starting in 2011.[67] The agreement was part of the debate over the future of the Māori electorates. National had a policy of abolishing the seats while the Māori Party wanted the seats entrenched in law. The Constitutional Review was agreed as a way to satisfy both parties.[68]

An advisory panel supported ministers Bill English and Pita Sharples, who were to make a final report to Cabinet by the end of 2013. The ministers' first report to Cabinet agreed on the make-up of the advisory panel, a plan for public engagement and how the review would interact with other government projects with a constitutional dimension, such as the referendum on MMP.[67] On 4 August 2011 the make-up of the advisory committee was announced, with former Ngāi Tahu leader Sir Tipene O'Regan and former law professor and law commissioner John Burrows as co-chairs.[69]

Māori constitutional working group

In 2010 the Iwi Chairs' Forum, a forum made up of people from iwi organisations across New Zealand set up a constitutional working group to create conversation with Māori how to develop a constitution for New Zealand from a Māori point of view.[70][71][72] The Iwi Chairs' Forum directed the working party to frame the conversation based on He Whakaputanga (the 1835 Declaration of Independence), Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and principles of tikanga. Chaired by Margaret Mutu and convened by Moana Jackson, the working group held 252 meetings with Māori at marae and other settings between 2012 and 2015.[71][73] The findings were launched in 2016 in a document called Matike Mai Aotearoa.[71][74]

See also

- Independence of New Zealand

- Politics of New Zealand

- Constitution of the United Kingdom, unwritten elements of which are incorporated into the New Zealand constitution

- Constitutionalism

References

Citations

- McDowell & Webb 2002, p. 101.

- Joseph, Philip (1989). "Foundations of the Constitution" (PDF). Canterbury Law Review. p. 72.

- Eichbaum & Shaw 2005, p. 33.

- Palmer, Matthew (20 June 2012). "Constitution - What is a constitution?". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- Eichbaum & Shaw 2005, p. 32.

- Palmer 2008, p. 17.

- McDowell & Webb 2002, p. 169.

- Geddis 2016, The political character of New Zealand’s constitution.

- McDowell & Webb 2002, p. 129.

- McDowell & Webb 2002, p. 114.

- Eichbaum & Shaw 2005, p. 37.

- Kumarasingham, Harshan (2008). Westminster Regained: The Applicability of the Westminster System for Executive Power in India, Ceylon and New Zealand after Independence (PDF) (Thesis). Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington. p. 12.

- Sir Kenneth Keith (2017). "On the Constitution of New Zealand: An Introduction to the Foundations of the Current Form of Government". Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- "The Treaty in brief - The Treaty in brief". NZHistory. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Palmer 2008, p. 139.

- Eichbaum, Chris. "The Cabinet office manual". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- Eichbaum & Shaw 2005, p. 36.

- Palmer, Matthew (20 June 2012). "Constitution - Constitutional conventions". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- Palmer 2008, p. 19.

- "Constitution Act 1986 (1986 No 114)". www.nzlii.org. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Quentin-Baxter & McLean 2017, p. 65.

- "What Does 'The Crown' Even Mean?". Royal Central. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- "The Royal assent". New Zealand Parliament. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- "The Reserve Powers". Governor-General of New Zealand. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- "New Zealand's first Constitution Act passed 165 years ago". www.parliament.nz. New Zealand Parliament. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Parliament Brief : What is Parliament?". New Zealand Parliament. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- "What is the Māori Electoral Option?". elections.nz. Electoral Commission New Zealand. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Palmer, Matthew (20 June 2012). "Constitution - Executive and legislature". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- "Couch v Attorney-General [2010] NZSC 27". 13 June 2008. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- "Privy Council delivers judgment in final appeal from New Zealand - Brick Court Chambers". www.brickcourt.co.uk.

- Privy Council Appeal, Pora (Appellant) v The Queen (Respondent) (New Zealand), judgment [2015] UKPC 9.

- UKSupremeCourt (3 March 2015). "Pora (Appellant) v The Queen (Respondent) (New Zealand)". Archived from the original on 21 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- Palmer 2008, p. 60.

- Palmer 2008, p. 91.

- Palmer 2008, p. 94.

- Palmer 2008, p. 109.

- Rishworth, Paul; Huscroft, Grant; Optican, Scott; Mahoney, Richard (2003). The New Zealand Bill of Rights. Oxford University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-19-558361-8.

- "Proclamation of Sovereignty over the North Island 1840". 21 May 1840. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Proclamation of Sovereignty over the South and Stewart Islands 1840". 21 May 1840. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Proclamation on the Illegal Assumption of Authority in the Port Nicholson District 1840". 23 May 1840. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "New Zealand Government Act of 1840 (3 and 4 Vict., ch. 62) (Imp)". 7 August 1840. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Royal Charter of 1840". 10 November 1840. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "William Hobson". Te Ara: Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 1990. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Auckland, Wednesday, Oct. 11, 1854". The New-Zealander. Vol. 10, no. 886. 11 October 1854. p. 2.

- Evans, Lewis (11 March 2010). "Law and the economy - Setting the framework". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- Kumarasingham 2010, p. 15.

- Kumarasingham 2010, p. 16.

- Kumarasingham 2010, p. 19.

- Kumarasingham 2010, p. 55.

- "Legislative Council abolished". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Senate Bill: Report of Electoral Law Committee". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 7 June 1994. Retrieved 15 October 2021 – via VDIG.net.

- Palmer 1979, chpt. 7.

- McDowell & Webb 2002, p. 156.

- McDowell & Webb 2002, p. 157.

- Wanna 2005, pp. 180–181.

- McDowell & Webb 2002, p. 162.

- McDowell & Webb 2002, p. 161.

- McDowell & Webb 2002, p. 168.

- Eichbaum & Shaw 2005, p. 44.

- "Section 271 Electoral Act 1993". Legislation.govt.nz.

- "Electoral Commission – Referendums". Archived from the original on 27 April 2005.

- "Electoral Commission – Referenda".

- "PM playing down constitutional review". TVNZ. 14 November 2004. Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Palmer & Butler 2016, p. 2.

- "National refuses to take part in constitution review". The New Zealand Herald. 14 November 2004. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- "Final Report of the Constitutional Inquiry" (PDF). 11 August 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2008.

- "Monarchy debate off-topic in constitutional review". TVNZ. 8 December 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- Boston, Butler & Morris 2011, p. 20.

- "'Good mix' in constitutional panel". The New Zealand Herald. 4 August 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- "Constitutional Working Group". Iwi Chairs Forum - Sharing the vision of Kotahitanga. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- "Report of Matike Mai Aotearoa – The Independent Working Group on Constitutional Transformation". Network Waitangi Otautahi. 26 July 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- "Tauiwi Engage with the Matike Mai Aotearoa Report | Treaty Resource Centre – He Puna Mātauranga o Te Tiriti". Treaty Resource Centre. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Potter, Helen; Jackson, Moana (9 April 2018). "Constitutional Transformation and the Matike Mai Project: A Kōrero with Moana Jackson". Economic and Social Research Aotearoa. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- "Moana Jackson - a new constitution for Aotearoa". RNZ. 23 October 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

Bibliography

- Boston, Jonathan; Butler, Petra; Morris, Caroline, eds. (2011). Reconstituting the Constitution. Springer. ISBN 9783642215711.

- Eichbaum, Chris; Shaw, Richard (2005). Public Policy in New Zealand - Institutions, processes and outcomes. Pearson Education New Zealand. ISBN 1877258938.

- Geddis, Andrew (January 2016). "Parliamentary government in New Zealand: Lines of continuity and moments of change". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 14 (1): 99–118. doi:10.1093/icon/mow001.

- Joseph, Philip (1993). Constitutional and Administrative Law in New Zealand (4th ed.). Thomson Reuters. ISBN 9780864728432.

- Kumarasingham, Harshan (2010). Onward with Executive Power - Lessons from New Zealand 1947-57. Institute of Policy Studies, Victoria University of Wellington. ISBN 978-1-877347-37-5.

- McDowell, Morag; Webb, Duncan (2002). The New Zealand Legal System (3rd ed.). LexisNexis Butterworths. ISBN 0408716266.

- Palmer, Geoffrey (1979). Unbridled Power: An Interpretation of New Zealand's Constitution & Government. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-558170-6.

- Palmer, Geoffrey; Butler, Andrew (2016). A Constitution for Aotearoa New Zealand. Victoria University Press. ISBN 9781776560868.

- Palmer, Geoffrey; Palmer, Matthew (2004). Bridled Power: New Zealand's Constitution and Government (4th ed.). South Melbourne, Vic. [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-58463-9.

- Palmer, Matthew (2008). The Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand's Law and Constitution. Victoria University of Wellington Press. ISBN 978-0-86473-579-9.

- Palmer, Matthew; Knight, Dean (2022). The Constitution of New Zealand - A Contextual Analysis. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781849469036.

- Quentin-Baxter, Alison; McLean, Janet (2017). This Realm of New Zealand: The Sovereign, the Governor-General, the Crown. Auckland University Press. ISBN 978-1-869-40875-6.

- Wanna, John (2005). New Zealand's Westminster trajectory: Archetypal transplant to maverick outlier. Sydney, NSW: UNSW Press. pp. 180–181. hdl:10072/262. ISBN 0868408484.

External links

- Constitution Aotearoa Archived 11 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- New Zealand Constitutional Law Resources

- Assent

- Cabinet Manual 2017

- Constitutional Advisory Panel interim website

- Response of the Government to the Report of the Constitutional Arrangements Committee

- Better Democracy – Group advocating binding citizens-initiated referendums.

- New Zealand Political and constitutional timeline – NZHistory.net.nz

- John McSoriley, The New Zealand Constitution, New Zealand Parliamentary Library, 2005