Nasr of Granada

Nasr (1 November 1287 – 16 November 1322), full name Abu al-Juyush Nasr ibn Muhammad (Arabic: أبو الجيوش نصر بن محمد), was the fourth Nasrid ruler[lower-alpha 1] of the Emirate of Granada from 14 March 1309 until his abdication on 8 February 1314. He was the son of Muhammad II al-Faqih and Shams al-Duha. He ascended the throne after his brother Muhammad III was dethroned in a palace revolution. At the time of his accession, Granada faced a three-front war against Castile, Aragon and the Marinid Sultanate, triggered by his predecessor's foreign policy. He made peace with the Marinids in September 1309, ceding to them the African port of Ceuta, which had already been captured, as well as Algeciras and Ronda in Europe. Granada lost Gibraltar to a Castilian siege in September, but successfully defended Algeciras until it was given to the Marinids, who continued its defense until the siege was abandoned in January 1310. James II of Aragon sued for peace after Granadan defenders defeated the Aragonese siege of Almería in December 1309, withdrawing his forces and leaving the Emirate's territories by January. In the ensuing treaty, Nasr agreed to pay tributes and indemnities to Ferdinand IV of Castile and yield some border towns in exchange for seven years of peace.

| Nasr | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sultan of Granada | |||||

| Reign | 14 March 1309 – 8 February 1314 | ||||

| Predecessor | Muhammad III | ||||

| Successor | Ismail I | ||||

| King of Guadix | |||||

| Reign | February 1314 – November 1322 | ||||

| Born | 1 November 1287 Granada, Emirate of Granada | ||||

| Died | 16 November 1322 (aged 35) Guadix, Emirate of Granada | ||||

| |||||

| House | Nasrid dynasty | ||||

| Father | Muhammad II | ||||

| Mother | Shams al-Duha | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Despite achieving peace with relatively minimal losses, Nasr was unpopular at court as he was suspected of being pro-Christian and accused of devoting so much time to astronomy that he neglected his duties as ruler. A rebellion started by his brother-in-law Abu Said Faraj in 1311 was initially repulsed, but a second campaign by Abu Said's son Ismail ended in the capture of the Alhambra palace and Nasr's abdication on 8 February 1314 in favour of Ismail, now Ismail I. He was allowed to rule the eastern province of Guadix, styling himself "King of Guadix", and attempted to regain the throne with help from Castile. Ismail defeated the Castilian forces in the Battle of the Vega of Granada, resulting in a truce that ended their support for Nasr. Nasr died without an heir in 1322.

Birth and early life

Abu al-Juyush Nasr ibn Muhammad[1] was born on 1 November 1287 (24 Ramadan 686 AH), likely in the Alhambra, the Nasrid fortress and royal complex in Granada.[3] His father was Muhammad II, (r. 1273–1302) the second Nasrid Sultan of Granada. His mother was Shams al-Duha, the second wife of Muhammad, a Christian and a former slave.[4] Muhammad had other children from his first wife: the firstborn Muhammad (later Muhammad III, born 1257, r. 1302–1309) and Fatima (c. 1260–1349). Their father, known by the epithet al-Faqih ("the canon-lawyer") due to his erudition and education, encouraged intellectual activities in his children; Muhammad was intensively engaged in poetry, while Fatima studied the barnamaj—the biobibliographies of Islamic scholars—and Nasr studied astronomy.[5] Nasr's much older brother Muhammad was named heir (wali al-ahd) during their father's reign.[3][6]

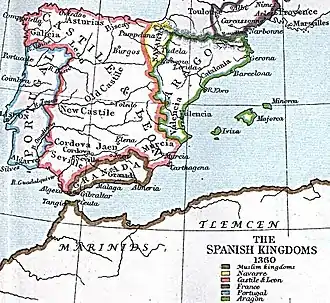

Muhammad III became the sultan after the death of their father in 1302. In the last few years of his reign, the emirate was on the verge of war against a triple alliance of its larger neighbors, the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon on the Iberian peninsula and the Marinid Sultanate in North Africa. The potentially disastrous war, as well as the extravagance of the vizier (chief minister) Ibn al-Hakim, sparked anger among the people of Granada. On 14 March 1309 (Eid ul-Fitr, 1 Shawwal 708 AH), a palace revolution instigated by a group of Granadan nobles including the vizier's rival, Atiq ibn al-Mawl, forced Muhammad III to abdicate in favor of Nasr. Muhammad III retired to an estate in Almuñécar, while Ibn al-Hakim was killed by Ibn al-Mawl during the turmoil and his corpse was defiled by a mob.[7][8] Nasr became the new sultan and appointed Ibn al-Mawl—the main instigator of the coup and a member of an influential family in Granada—as his vizier.[8]

War against the triple alliance

Granada was in a very dangerous situation when Nasr took power, without allies and with three larger enemies preparing for war against it. One of the main points of contention was Granada's occupation of Ceuta, a port on the North African coast of the Strait of Gibraltar which had rebelled against the Marinids in 1304 and was conquered by Granada in 1306 during Muhammad III's reign.[9] The Granadan capture of Ceuta, in addition to its control of Algeciras and Gibraltar, other ports in the Strait, as well as Málaga and Almería further east, had given it strong control of both sides of the Strait, alienating not only the Marinids but also Castile and Aragon.[10][11]

The Marinids commenced an attack against Ceuta on 12 May 1309 and secured a formal alliance with Aragon in early July. Aragon was to send galleys and knights to help the Marinids take Ceuta in exchange for deliveries of wheat and barley to Aragon, commercial benefits for Catalan traders in Morocco and agreement for both parties to not make a separate peace. The agreement also stipulated that, once captured, the territory would be handed back to the Marinids but the port would first be sacked and all movable goods would be given to Aragon.[12] However, on 20 July 1309, the people of Ceuta overthrew their Nasrid rulers and allowed the Marinids to enter the city without Aragonese help. The return of Ceuta softened the Marinid stance against Granada and the two Muslim states then entered into negotiations.[13] Nasr had already sent his envoys to the Marinid court at Fez since April and, by late September 1309, a peace agreement was reached.[12] In addition to accepting Marinid rule over Ceuta, Nasr had to yield Algeciras and Ronda—both in Europe—and their surrounding territories.[13] Thus, the Marinids once again had outposts on Granada's traditional territories on the southern Iberian peninsula, after their last withdrawal in 1294.[9] No longer needing help from Aragon, the Marinids discarded the alliance between them and did not send the booty from Ceuta as promised; soon King James II of Aragon wrote to his Castilian counterpart Ferdinand IV about the Marinid Sultan Abu al-Rabi Sulayman, "It seems to us, King, that from now on we can regard that king as an enemy".[14]

Meanwhile, at the end of July 1309 the Christian forces, including not only the forces of Castile and Aragon but also those of Portugal, who joined the alliance on 3 July 1309, laid siege to Algeciras, a port in the western end of the Emirate, led by Ferdinand IV. Soon, a detachment of this force also besieged nearby Gibraltar. Two siege engines attacked the walls of Gibraltar while Aragonese ships blockaded its port. The city surrendered on 12 September 1309, just before Nasr's peace with the Marinids. The city's mosque was converted into a church, and 1,125 of its inhabitants left for North Africa rather than live under Christian rule. Although this port was less important than Algeciras, its conquest was still significant as it gave Castile a strategic foothold on the Straits of Gibraltar.[15] It would return to Muslim hands in 1333, and again to Castile in 1464, in a long struggle for the ports on the strait.[16] The siege of Algeciras remained underway, and as per the Granada–Marinid peace settlement, the city changed hands to the Marinids, for whom the garrison now fought. The Marinids sent troops and supplies to reinforce the city, while Nasr redirected his attention to the eastern front.[17] In either late October or November,[9][18] a contingent of 500 Castilian knights led by the king's uncle Infante John and the king's cousin Juan Manuel left the siege of Algeciras, demoralizing the rest of the besiegers and making them vulnerable to a counterattack. Ferdinand IV was still determined to continue the siege, vowing that he preferred death in battle to the dishonour of withdrawing from Algeciras.[18]

On the eastern front, Aragonese troops besieged Almería with some support from Castile. The city managed to stockpile supplies and improve its defenses due to the late arrival of the Aragonese forces, led by James II, by sea in mid-August 1309.[19] A series of assaults against the city failed, and Nasr sent troops under Uthman ibn Abi al-Ula to relieve it. They took a position in nearby Marchena after defeating an Aragonese contingent there and continuously harassed the besieger's foraging parties.[20][21] By the time winter approached, the city still held out, and the weakening of the siege of Algeciras in November meant that Granada could send more reinforcements to the east. At the end of December, James II and Nasr agreed to a truce and that the Aragonese king would evacuate his troops from Granadan territories. The evacuation was completed in January 1310 after some incidents.[19] At one point during the evacuation, Nasr wrote to James that the city's defenders had to put the remaining Aragonese troops under detention because they were pillaging Granadan territories. Nasr further noted that the Muslims gave them housing and food at their own expense "because some of them were starving" while waiting for the Aragonese ships to pick them up.[22]

Ferdinand IV's siege of Algeciras made little progress, and by January 1310 he lifted the siege and entered into talks with Nasr.[19] Hostilities still continued—for instance, Castilian troops under the king's brother, Infante Peter, captured Tempul (near Jerez) and the Castilian-Aragonese fleet still patrolled Granadan waters in May.[23] A seven-year peace treaty was signed on 26 May 1310; Nasr agreed to pay an indemnity of 150,000 gold doblas and an annual tribute of 11,000 doblas to Castile. In addition to Gibraltar, Granada yielded some frontier towns, including Quesada and Bedmar, gained by Muhammad III in the previous war. Both monarchs agreed to help each other against their enemies; Nasr became a vassal of Castile and was to provide up to three months of military service per year if summoned, with his own troops and at his own expense. Markets would be opened between the two kingdoms, and Ferdinand IV was to appoint a special judge of the frontiers (juez de la frontera) to adjudicate disputes between Christians and Muslims in the border regions. No historical records of a Granada-Aragon treaty are found, but it is known that Nasr agreed to pay James II 65,000 doblas in indemnity, 30,000 of which was to be given by Ferdinand IV.[24]

The Marinid presence on the Iberian Peninsula proved to be short-lived. Abu al-Rabi died in November 1310 and was succeeded by Abu Said Uthman II, who wanted to further expand his Iberian territories. He sent a fleet across the strait, but it was defeated by Castile off Algeciras on 25 July 1311. He decided to disengage and returned his Iberian holdings, including Algeciras and Ronda, to Nasr.[24]

Rebellion and downfall

Despite his success in ending the three-front war with minimal losses, Nasr and his vizier Ibn al-Hajj—who replaced Ibn al-Mawl when the latter fled to North Africa[25]—soon became unpopular at court.[19] The historian L. P. Harvey writes that the reason is not clear, and while the near-contemporary scholar Ibn Khaldun writes that this was due to their "tendencies towards violence and injustice", Harvey rejects this as a "hostile propaganda".[26] The Arabist scholar Antonio Fernández-Puertas linked their unpopularity to Nasr's pursuit of science, which was deemed excessive by his nobles, as well as the suspected pro-Christian tendencies of the sultan and the vizier. Nasr was said to spend too much time building astrolabes and astronomical tables, neglecting his duties as monarch. The suspicion of pro-Christian sympathy stemmed from his education by his Christian mother and his good relationship with Ferdinand IV. Ibn al-Hajj was also unpopular as he was believed to have too much power over the sultan. Compounding their image problem, they both often dressed in the Castilian manner.[27]

In November 1310, Nasr fell gravely ill, and a faction at court attempted to restore Muhammad III. The old and nearly blind former sultan was transported by litter from Almuñécar. The plot failed when Nasr recovered before Muhammad was enthroned; Nasr then imprisoned his brother in the Dar al-Kubra (La Casa Mayor, "Big House") of the Alhambra.[28] Nasr later had his brother drowned, although there are conflicting reports of when this happened. Ibn al-Khatib listed four dates: mid-February 1311, February or March 1312, 12 February 1312, and 21 January 1314.[29] Historian Francisco Vidal Castro, who considered all four dates, considers the latest date to be the valid one because it also appears in other credible reports as well as on Muhammad's tombstone.[28]

The leader of the next rebellion was Abu Said Faraj, the governor of Málaga and a member of the Nasrid dynasty.[30] He was a nephew of Muhammad I, Nasr's grandfather and the founder of the emirate, as well as Nasr's brother-in-law as he was married to Nasr's sister, Princess Fatima.[31] When Abu Said paid his annual homage to Nasr, he found that the sultan was unpopular at court. He also disliked what he heard about Nasr; according to Fernández-Puertas, Abu Said was further outraged at the death of the Muhammad III.[27]

Abu Said started his rebellion in Málaga in 1311.[27] Rather than proclaiming himself sultan, he declared for his son, Ismail, who had the added legitimacy of being the grandson of Muhammad II through his mother Fatima.[27][32] The Málagan rebels were supported by North African forces under Uthman ibn Abi al-Ula, the commander of the Volunteers of the Faith garrisoned in Málaga, while other North African forces under the princes Abd al-Haqq ibn Uthman and Hammu ibn Abd al-Haqq supported Nasr.[26] The rebels took Antequera, Marbella and Vélez-Málaga, advanced to the Vega of Granada and defeated Nasr's forces at a place called al-Atsha by Arabic sources, possibly today's Láchar.[27][33] During the battle, Nasr fell from his horse and lost it, and had to run back to Granada on foot. Abu Said proceeded to besiege the capital but lacked the necessary supplies for a protracted campaign.[27] Nasr requested help from Ferdinand IV, and Castile's forces under Infante Peter defeated Abu Said and Ismail on 28 May 1312.[34] Abu Said sought peace and was able to retain his post as governor of Málaga and resumed paying tributes to the sultan.[27] Subsequently, Nasr also paid his annual tribute to Castile in August 1312, shortly before Ferdinand IV died and was succeeded by his one-year-old son Alfonso XI.[34]

Opposition to Nasr continued, and members of the anti-Nasr faction fled the court for Málaga.[33] Soon Ismail restarted the rebellion with help from his mother Fatima and Uthman ibn al-Ula.[4] As Ismail moved towards Granada, his army swelled and the capital's inhabitants opened the city gates for him. Ismail entered the city from the Elvira (Ilbira) Gate and besieged Nasr, who remained in the Alhambra.[35] Nasr tried to request help from Infante Peter (now one of the regents for the infant king), but aid did not come in time.[34] Nasr was forced to abdicate on 8 February 1314 (21 Shawwal 713 AH).[19] In exchange for surrendering the Alhambra, he was permitted to leave for Guadix and rule there as governor.[19][35] Abd al-Haqq ibn Uthman and Hammu ibn Abd al-Haqq accompanied him there.[19][26]

Attempt to regain the throne

After Nasr's defeat and move to Guadix, he still maintained his claim to the throne.[36] He styled himself "King of Guadix" and led a group of his relatives and servants to resist Ismail. Ismail besieged Nasr at Guadix in May 1315 but left after 45 days.[3] Nasr repeatedly requested help from Castile, which was ruled by a regency made up of Infante Peter, Infante John, and the king's grandmother María de Molina.[37] Peter agreed to meet Nasr and help him, but separately he also told James II of Aragon that he intended to conquer Granada for himself, and would give one-sixth of it to Aragon in exchange for help. In January 1316, Nasr reiterated to James II that the upcoming campaign was to restore himself as Sultan of Granada.[36] Nasr offered to give Guadix to Peter in exchange for his help if Nasr succeeded in retaking the throne.[3]

Preparation for Castile's campaign began in spring of 1316.[36] On 8 May, Granadan forces under Uthman ibn Abi al-Ula intercepted a Castilian column supplying Nasr, who was again besieged at Guadix. A battle then took place near Alicún, in which Castilian forces led by Peter and supported by Nasr routed the Granadan royal forces, killing 1,500 and causing them to withdraw to Granada.[38] Subsequently, the war dragged on for several years, punctuated by several short truces.[39] The climax of the war took place on 25 June 1319, when a Granadan force led by Ismail battled the Castilian army in the Vega of Granada.[40] The Castilian commanders and regents John and Peter both died without combat during the battle, possibly due to cardiac arrest.[41] Ismail's forces then routed the demoralized Castilian forces.[40] The defeat and death of the two regents made Castile leaderless, threw it into internal turmoil, and gave Ismail the upper hand.[37][42] Due to the lack of royal leadership, Hermandad General de Andalucía—a regional confederation of frontier towns—acted to negotiate with Granada.[43] A truce was agreed by the hermandad and Ismail at Baena on 18 June 1320, meant to last for eight years.[19][44] One of the provisions was that the Castilians would not help any other Moorish king, which meant the end of support for Nasr.[44]

Nasr died in Guadix without an heir on 16 November 1322 (6 Dhu al-Qaida 722 AH) at the age of 35,[3] ending the direct male line of the Nasrid dynasty from Muhammad I, the founder of the emirate.[19][35][26] Subsequent Sultans of Granada would descend from Ismail, whose father came from a collateral branch of the dynasty, but whose mother Fatima was Muhammad I's granddaughter.[35] Nasr's lack of heir ensured the dynasty's unity for the time being,[26] and Ismail peacefully reincorporated territories formerly under Nasr's control to the Emirate.[35] Nasr was initially buried at the main mosque of Guadix, but subsequently moved to the Sabika Hill of the Alhambra alongside his grandfather Muhammad I and brother Muhammad III.[3]

Character and legacy

Official biographies described Nasr as being elegant, gentlemanly, chaste and peace-loving. He was knowledgeable in astronomy, tutored by Muhammad ibn al-Raqqam (1250–1315), a Murcian astronomer who settled in Granada at the invitation of Muhammad II. Nasr personally authored various almanacs and astronomical tables.[3] He also became a patron for a notable doctor of his time, Muhammad al-Safra of Crevillente, who followed him as personal physician in Guadix after he was dethroned.[45] Nasr was responsible for building the Tower of Abu al-Juyush in the Alhambra, a rectangular tower rising above the city wall built by Muhammad II, to which it is connected by a hidden staircase that further leads into an underground route leading out of the palace complex. It is now better known as the location of the Peinador de la Reina (The Queen's Dressing Room) after its use by Isabella of Portugal, consort of Emperor Charles V. The tower was likely used and further renovated by Nasr's successors, and Yusuf I—son of Ismail I, who dethroned Nasr—attempted to replace references to Nasr in the tower with his own name.[46]

To traditional and modern historians, Nasr's abdication in favour of Ismail I marked the end of al-dawla al-ghalibiyya al-nasriyya, "the Nasrid dynasty of al-Ghalib", whose rulers are patrilineally descended from Muhammad I—also known by the epithet "al-Ghalib billah"—and the beginning of a new branch: al-dawla al-isma'iliyya al-nasriyya, "the Nasrid dynasty of Ismail".[35][47] The Nasrid dynasty did not have a specific rule of succession, but Ismail I was the first of the few rulers who only descended matrilineally from the royal line. The other instance happened in 1432 with the accession of Yusuf IV.[47]

Notes

References

Citations

- Latham & Fernández-Puertas 1993, p. 1020.

- Rubiera Mata 2008, p. 293.

- Vidal Castro.

- Catlos 2018, p. 343.

- Rubiera Mata 1996, p. 184.

- Rubiera Mata 1969, pp. 108–109, note 5.

- Harvey 1992, pp. 169–170.

- Rubiera Mata 1969, p. 114.

- Harvey 1992, p. 172.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 122.

- Arié 1973, p. 267.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 127.

- Latham & Fernández-Puertas 1993, p. 1022.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 127–128.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 128–129.

- Harvey 1992, p. 173.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 129–130.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 130.

- Latham & Fernández-Puertas 1993, p. 1023.

- Harvey 1992, p. 175.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 132.

- Harvey 1992, p. 179.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 132–133.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 133.

- Rubiera Mata 1969, p. 115.

- Harvey 1992, p. 180.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 4.

- Vidal Castro 2004, p. 361.

- Vidal Castro 2004, pp. 362–363.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, pp. 2–3.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, pp. 2–4.

- Rubiera Mata 1975, pp. 131–132.

- Rubiera Mata 1975, p. 132.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 134.

- Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 5.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 138.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 137.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 139.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 139–143.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 144.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 144–145.

- Harvey 1992, p. 182.

- O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 147–148.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 147.

- Arié 1973, p. 430.

- Fernández-Puertas & Jones 1997, p. 247.

- Boloix Gallardo 2016, p. 281.

Bibliography

- Arié, Rachel (1973). L'Espagne musulmane au temps des Nasrides (1232–1492) (in French). Paris: E. de Boccard. OCLC 3207329.

- Boloix Gallardo, Bárbara (2016). "Mujer y poder en el Reino Nazarí de Granada: Fatima bint al-Ahmar, la perla central del collar de la dinastía (siglo XIV)". Anuario de Estudios Medievales (in Spanish). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. 46 (1): 269–300. doi:10.3989/aem.2016.46.1.08.

- Catlos, Brian A. (2018). Kingdoms of Faith: A New History of Islamic Spain. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-17-8738-003-5.

- Fernández-Puertas, Antonio (April 1997). "The Three Great Sultans of al-Dawla al-Ismā'īliyya al-Naṣriyya Who Built the Fourteenth-Century Alhambra: Ismā'īl I, Yūsuf I, Muḥammad V (713–793/1314–1391)". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Third Series. London: Cambridge University Press on behalf of Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 7 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1017/S1356186300008294. JSTOR 25183293. S2CID 154717811.

- Fernández-Puertas, Antonio; Jones, Owen (1997). The Alhambra: From the ninth century to Yūsuf I (1354). London: Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0863564666. OCLC 929440128.

- Harvey, L. P. (1992). Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31962-9.

- Latham, J.D. & Fernández-Puertas, Antonio (1993). "Naṣrids". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VII: Mif–Naz (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1020–1029. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (2011). The Gibraltar Crusade: Castile and the Battle for the Strait. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0463-6.

- Rubiera Mata, María Jesús (1969). "El Du l-Wizaratayn Ibn al-Hakim de Ronda" (PDF). Al-Andalus (in Spanish). Madrid and Granada: Spanish National Research Council. 34: 105–121.

- Rubiera Mata, María Jesús (1975). "El Arráez Abu Sa'id Faray B. Isma'il B. Nasr, gobernador de Málaga y epónimo de la segunda dinastía Nasari de Granada" (PDF). Boletín de la Asociación Española de Orientalistas (in Spanish). Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: 127–133. ISSN 0571-3692.

- Rubiera Mata, María Jesús (2008). "El Califato Nazarí". Al-Qanṭara (in Spanish). Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. 29 (2): 293–305. doi:10.3989/alqantara.2008.v29.i2.59. ISSN 0211-3589.

- Rubiera Mata, María Jesús (1996). "La princesa Fátima Bint Al-Ahmar, la "María de Molina" de la dinastía Nazarí de Granada". Medievalismo (in Spanish). Murcia and Madrid: Universidad de Murcia and Sociedad Española de Estudios Medievales. 6: 183–189. ISSN 1131-8155. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2019.

- Vidal Castro, Francisco. "Nasr". Diccionario Biográfico electrónico (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia.

- Vidal Castro, Francisco (2004). "El asesinato político en al-Andalus: la muerte violenta del emir en la dinastía nazarí". In María Isabel Fierro (ed.). De muerte violenta: política, religión y violencia en Al-Andalus (in Spanish). Editorial – CSIC Press. pp. 349–398. ISBN 978-84-00-08268-0.

.svg.png.webp)