Malta Railway

The Malta Railway was the only railway line ever on the island of Malta, and it consisted of a single railway line from Valletta to Mdina. It was a single-track line in metre gauge, operating from 1883 to 1931. The railway was known locally in Maltese as il-vapur tal-art (the land ship).

| |

Exit of a train from Valletta station | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Valletta |

| Locale | Malta |

| Dates of operation | 1883–1931 |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) metre gauge |

| Length | 7 mi (11 km) |

History

.jpg.webp)

The first proposal to build a railway in Malta was made in 1870 by J. S. Tucker. The main reason was to connect the capital Valletta with the former capital Mdina so the journey time between the two cities would be reduced from 3 hours to less than half an hour. A narrow-gauge railway system designed by John Barraclough Fell was initially proposed. In 1879, this was dropped in favour of a design by the engineering firm of Wells-Owen & Elwes, London. In 1880, the newspaper The Malta Standard reported that "in a short space of time, the inhabitants of these Islands may be able to boast of possessing a railway", and that the line was to be open by the end of 1881.[1]

There were some problems with the acquisition of land to build the railway, so construction took longer than expected. The line was opened on 28 February 1883 at 3pm, when the first train left Valletta and arrived at Mdina after about 25 minutes.[2]

Finances of the railway always proved critical. On 1 April 1890 the first proprietor, the Malta Railway Company Ltd., went bankrupt and the railway stopped running. As a result of this the government took over the railway, invested in its infrastructure and reopened traffic on 25 January 1892. From 1895 on an extension of the line was under work aiming for the barracks at Mtarfa behind the historic city of Mdina. This extension was opened for traffic in 1900.[3]

In 1903 a company was founded which ran tramways on Malta from 1905 on, partly parallel to the railway line, and this competition had a negative effect on the railway's finances. The first buses were introduced in 1905 and became popular in the 1920s. This contributed to the decline of both the railway as well as the tramway. The tram company closed in 1929, while the railway line stopped operating on 31 March 1931.[3]

During the siege of Malta in World War II, the railway tunnel running under the fortifications of Valletta was used as an air-raid-shelter. In 1940, Mussolini proclaimed that an Italian air raid destroyed the Maltese railway system, even though the railway had been closed for nine years.

Over the years, long stretches of the former railway line were surfaced with tarmac and converted into roads. Some of the railway buildings are still in existence.

Line

Malta Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The line connected Valletta and Mdina and a number of settlements in between. The first two stations, Valletta and Floriana, were underground. The Line extended over 11.1 km / 6.9 mi, climbing 150 meters / 500 feet at a maximum of 25 Per mil. The line crossed roads by 18 level crossings of which 14 were staffed. The roads were chained off when a train was approaching. Originally the line was constructed with rails of 42 pounds per foot and replaced when the government took over the railway in 1890 by those of 60 pound per foot to allow heavier locomotives to run on the line.[5]

The alignment of the tunnel had to meet the requirement of both military and civil authorities, which caused considerable debate before a decision was reached, but it was subsequently discovered that the alignment would intersect an ancient subterranean reservoir, the position of which up until then had not been known. In order to keep to the agreed entrances the tunnel itself was deviated around the reservoir, giving it a double S-curve in the middle. This deviation was achieved with an alignment error of only 1 inch.[6]

Vehicles

Locomotives

The original locomotives were six-coupled tank engines by Manning Wardle of Leeds with 10 1/2 inch cylinders with 18 inch stroke. They had provision for turning the exhaust steam into the tank when in tunnels to improve the air quality.[6]

During its lifetime the railway had only 10 locomotives. In addition to those by Maning Wardle, these were built by Black, Hawthorn & Company of Gateshead and Beyer, Peacock & Company of Manchester. Most of them were 2-6-2 and 2-6-4 engines. They were painted in olive on black frames. None of them are preserved.[7]

The engine and carriage sheds were at Hamrun.

Carriages

The carriages were supplied by the Railway Carriage Company, Oldbury,[6] and were wooden on iron frames. First and third class was provided. The seats were parallel to the line on both sides of an aisle. Originally illuminated by candles, this was changed to electricity, powered by batteries, in 1900. When the railway stopped running, 34 carriages were in use. One third-class carriage is preserved, was restored and placed beside the former station building of Birkirkara but, as of 2014, is now rather dilapidated.[7] It is now being renovated and will be repositioned near the original location.

Traffic

A train usually consisted of five carriages, while trains running over the maximal climb before Notabile had only four. After more powerful engines were used, trains up to 12 carriages became possible. During World War I, even longer trains were run using two locomotives. Travelling time inland (that is, uphill) was 35 minutes; downhill, in the direction of Valletta, 30 minutes. Initially quite a busy timetable was in use with 13 pairs of trains running the whole of the line and an additional two or three pairs between Valletta and Attard, Valletta and Birkirkara and Valletta and Ħamrun.

Present day

Remains of the Malta Railway

Various parts of the railway still exist to this day, most notably the stations at Birkirkara and Mdina, along with various bridges and tunnels. Various roads which were built instead of the railway retain names such as Railway Road in Santa Venera and Railway Street in Mtarfa.

The station at Valletta was damaged during World War II and was demolished in the 1960s to make way for Freedom Square. Its site is now occupied by the Parliament House. The railway tunnel adjacent to the station was used as a garage (Yellow Garage), but it was closed in 2011 as part of the City Gate Project. The modern structures within the tunnel have since been demolished, restoring it to its original state. Works are also being made on the bridge near the tunnel.[9]

The ticket office at Floriana still exists. A former railway tunnel under St Philip's Gardens was reopened in 2011 and has been open for visitors on various occasions since then. Two original luggage trolleys were found within the tunnel, but in a very dilapidated state.[10] The bridge which linked the tunnel with the rest of the line still exists, although it is overgrown.

The Ħamrun station is now used as the headquarters of the 1st Hamrun Scout Group.[11]

The former station in Birkirkara is currently used as a child care centre, but plans are being made to turn it into a museum known as the Birkirkara Historical Malta Railway Museum. The garden near the station, Ġnien l-Istazzjon (Station Garden), contains the only surviving carriage of the railway, which has been recently restored.[12] When the station is converted into a museum, the garden will also be refurbished, and the carriage will be restored and repositioned.[13] At the beginning of April 2017 the carriage has been taken to renovate.[14]

On the place where there was Attard Station is now known as Gnien L-Stazzjoni, which is close to San Anton Gardens. In Attard there is the Malta Railway Museum, a small private museum, which is open to the public on demand, that was opened in 1998. It shows photographs, documents and other memorabilia of the railway, in addition to models of eight segments of the line reconstructed in a ratio 1:148 by Nicholas Azzopardi between 1981 and 1985.[15]

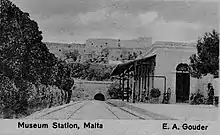

The former Museum Station near Mdina was converted into the Stazzjon Restaurant in 1986. The restaurant also contained many railway-related photos and a model locomotive.[16] It closed down in 2011. But in 2016 it was reopened and is known as L-Istazzjon.[9]

- Remains of the Malta Railway

_02_ies.jpg.webp) Railway tunnel and bridge, Valletta

Railway tunnel and bridge, Valletta Railway bridge near Saint Philip's Bastion, Floriana

Railway bridge near Saint Philip's Bastion, Floriana Station in Birkirkara.

Station in Birkirkara. Museum Station, Mdina

Museum Station, Mdina.jpg.webp) Railway bridge near Museum Station

Railway bridge near Museum Station

Possibility of a new railway

In May 2015, the Transport Minister Joe Mizzi said that the government is considering the introduction of a surface railway system in order to reduce traffic congestion.[17]

References

- "The Malta Railway" (PDF). The Malta Standard. 8 December 1880. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- "Opening of the Malta Railway" (PDF). The Malta Standard. 1 March 1883. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Azzopardi, Nicholas. "Brief History". maltarailway.com. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Atlante ferroviario d'Italia e Slovenia [Railway atlas of Italy and Slovenia] (in Italian). Cologne: Schweers + Wall. 2010. p. 110. ISBN 978-3-89494-129-1.

- "The Route". maltarailway.com. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- "The Malta Railway". The Engineer: 280. 13 Apr 1883.

- "Locomotives & Rolling Stock". maltarailway.com. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Carabott, Sarah (1 September 2016). Malta's only surviving train carriage to get funds for restoration. Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016.

- "Walking the Old Malta Railway". faydon.com. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Calleja, Claudia (22 October 2012). "Railway tunnel part of Malta's heritage". Times of Malta. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- "Our History". 1st Hamrun Scout Group. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Boulter, Peter (15 November 2009). "Old railway carriage rotting away". Times of Malta. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Ameen, Juan (26 September 2014). "It's full steam ahead for railway museum". Times of Malta. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Carabott, Sarah (7 April 2017). "Watch: Malta's last surviving train carriage chugs toward restoration". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017.

- "Malta Railway Museum". maltarailway.com. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- "Museum Restaurant". maltarailway.com. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- "Government might consider surface railway system - minister". Times of Malta. 21 May 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- Bonnici, Joseph; Cassar, Michael (1992). The Malta Railway. Malta.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

- Balzan, Carmel J. (1959). "Notifikazzjonijiet tal-Gvern fis-Seklu XIX" (PDF). L-Imnara. 1 (3): 58.