Nadezhda Durova

Nadezhda Andreyevna Durova (Russian: Надежда Андреевна Дурова; September 17, 1783 – March 21, 1866), also known as Alexander Durov, Alexander Sokolov and Alexander Andreevich Alexandrov, was a Russian cavalry soldier and writer who participated in the Napoleonic Wars.

Nadezhda Durova | |

|---|---|

| Надежда Дурова | |

Portrait by Woldemar Hau, 1837 | |

| Born | September 17, 1783 |

| Died | March 21, 1866 (aged 82) Yelabuga, Russia |

Born a woman, she ran away from home and dressed as a man while enlisting in an uhlan (light cavalry) regiment.[1] She participated in the war, and published her memoirs after her service. She was one of the first known female officers in the Russian military. She received the Cross of St. George for bravery.[1] Her memoir, The Cavalry Maiden, is a significant document of its era because few junior officers of the Napoleonic Wars published their experiences, and because it is one of the earliest autobiographies in the Russian language.[2]

Early biography

Nadezhda Durova was born on September 17, 1783,[3] into the family of a Russian major.[4][3] Some sources say she was born in Vyatka Governorate of the Russian Empire,[5] while other sources say she was born in an army camp in Kiev,[6][7] or in the city of Kherson.[3] Her mother came from a family of wealthy landowners from Poltava, and married Nadezhda's father against the will of her own father; a son was desired, but instead, Nadezhda was born, much to the dismay of her mother.[8][9] Her father placed her in the care of his soldiers after an incident that nearly killed her in infancy when her abusive mother threw her out the window of a moving carriage. As a small child, Durova learned all the standard marching commands and her favorite toy was an unloaded gun.[10]

After her father retired from service, she continued playing with broken sabers and frightened her family by secretly taming a stallion that they considered unbreakable.[11] In 1801, she married a Sarapul judge, Vasily Stefanovich Chernov, who was seven years her senior, and gave birth to a son on January 4, 1803.[12] On September 17, 1806,[13][3] she dressed as a man in a Cossack uniform and ran away from home,[13] enlisting in the Polish Horse Regiment (later classified as uhlans) under the alias Alexander Sokolov.[12][4]

Fiercely patriotic, Durova regarded army life as freedom. She enjoyed animals and the outdoors, but felt she had little talent for traditional women's work. In her memoirs she describes an unhappy relationship with her mother, warmth toward her father, and nothing at all about her own married life.

Military service and later life

She fought in the major Russian engagements of the 1806–1807 Prussian campaign. During two of those battles, she saved the lives of two fellow Russian soldiers. The first was an enlisted man who fell off his horse on the battlefield and suffered a concussion. She gave him first aid under heavy fire and brought him to safety as the army retreated around them. The second was an officer, unhorsed but uninjured. Three French dragoons were closing on him. She couched her lance and scattered the enemy. Then, against regulations, she let the officer borrow her own horse to hasten his retreat, which left her more vulnerable to attack.

During the campaign, she wrote a letter to her family explaining her disappearance. They used their connections in a desperate attempt to locate her. The rumor of an amazon in the army reached Tsar Alexander I, who took a personal interest. Durova's chain of command reported that her courage was peerless. Summoned to the palace at St. Petersburg, she impressed the tsar so much that he awarded Durova the Cross of St. George and promoted her to lieutenant in a hussar unit (Mariupol Hussar Regiment). The story that there was the heroine in the army with the name Alexander Sokolov had become well-known by that time. So the tsar awarded her a new pseudonym, Alexandrov, based on his own name.[14]

Durova's youthful appearance hurt her chances for promotion. In an era when Russian officers were expected to grow a mustache, she looked like a boy of sixteen. She transferred away from the hussars to the Lithuanian Uhlan Regiment in order to avoid the colonel's daughter who had fallen in love with her. Durova saw action again during Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812. She fought in the Battle of Smolensk. During the Battle of Borodino, a cannonball wounded her in the leg, yet she continued serving full duty for several days afterward until her command ordered her away to recuperate. She retired from the army in 1816 with the rank of stabs-rotmistr, the equivalent of captain-lieutenant.[14]

A chance meeting introduced her to Aleksandr Pushkin some 20 years later. When he learned that she had kept a journal during her army service he encouraged her to publish it as a memoir. She added background about her early childhood but changed her age by seven years and eliminated all reference to her marriage. Durova published this as The Cavalry Maiden in 1836. Durova also wrote five other novels.[15] Durova continued to wear male clothing for the rest of her life, continued to use her male alias, and spoke using masculine grammar.[16] She died in Yelabuga and was buried with full military honors.[14] Her son, Ivan Durov, had died 10 years prior, in 1856.[12]

Durova's gender identity

There has been a debate over whether Durova could be labelled as a transgender man. Much of the scholarship concerning Durova treats her as a cross-dressing woman;[17] however, Durova in her personal life rejected femininity (even expressing an aversion to the female sex),[18] and behaved as a man.[16] In The Cavalry Maiden, Durova describes herself with terms of androgyny, describing herself both as a bogatyr[19] and as an Amazon warrior. Durova was also a writer of prose, and one of her stories, Nurmeka, revolves around a male who cross-dresses as a female, leading to speculation that this was an expression of Durova's transgender identity.[18] Terms relating to non-standard gender identity such as transvestite (1910), transsexual (1949), and transgender (1971) were coined long after Durova's death,[20] so she could not have used the modern label of transgender; despite this, modern scholarship has increasingly adopted the view that Durova may have been an example of a transgender individual.[21][22]

Legacy

Besides being a rare example of a female soldier's military memoir, The Cavalry Maiden is one of the few sustained accounts of the Napoleonic wars to describe events from the perspective of a junior officer and one of the earliest autobiographical works in Russian literature.

Durova became a figure of some cultural interest in Eastern Europe but remained largely unknown to the English-speaking world until Mary Fleming Zirin's translation of The Cavalry Maiden in 1988. Durova is now a subject of university syllabi and scholarly publications in comparative literature and Russian history.

Artistic works about Nadezhda Durova

- Nadezhda Durova, an opera by Anatoly Bogatyrev.

- A Long Time Ago, a play by Alexander Gladkov.

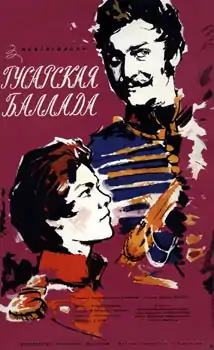

- Hussar Ballad, an operetta by Tikhon Khrennikov

- Hussar Ballad, a film directed by Eldar Ryazanov.

- The Girl Who Fought Napoleon: A Novel of the Russian Empire, a novel by Linda Lafferty

Bibliography

- Durova, Nadezhda, The Cavalry Maiden: Journals of a Russian Officer in the Napoleonic Wars. Mary Fleming Zirin. Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-253-20549-2 (see book reviews on Amazon.com).

See also

Notes

- Pushkareva, Natalia (3 March 1997). Women in Russian History: From the Tenth to the Twentieth Century. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-0-7656-3270-8.

- Robinson, Lillian S.; Women, Stanford University Center for Research on (1 January 1990). Revealing Lives: Autobiography, Biography, and Gender. SUNY Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7914-0435-5.

- Wilson, Katharina M. (1991). An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers. Taylor & Francis. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-8240-8547-6.

- Cook, D.; Wall, J. (21 June 2011). Children and Armed Conflict: Cross-disciplinary Investigations. Springer. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-230-30769-8.

- Cook, Bernard A., ed., Women and War: A Historical Encyclopedia from Antiquity to the Present, Volume 2 (2006), p. 156. ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA. ISBN 1-85109-770-8

- Mauricio Borrero. Russia: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. 2004. P. 135. ISBN 9780816074754

- Hagemann, Karen; Dudink, Stefan; Rose, Sonya O. (2020). The Oxford Handbook of Gender, War, and the Western World Since 1600. Oxford University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-19-994871-0.

- "Кавалерист-трансгендер | О книге про жизнь и творчество Надежды Дуровой" [Transgender Cavalerist : A Book About the Life and Career of Nadezhda Durova]. «Горький медиа» (in Russian). 16 January 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- "Durova Nadezhda Andreyevna". Russian Biographica Dictionary (in Russian). Vol. 6. 1906. pp. 723–726. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- Mersereau, John Jr.; Lapeza, David (1988). Nadezhda Durova: The Cavalry Maid. Ardis. ISBN 0-87501-032-6.

- Mersereau & Lapeza, p. 21

- Aykasheva, Olga (2014). "Судьба Ивана Чернова сына Н. А. Дуровой" [THe fate of Ivan Chernov, son of N.A. Durova]. Locus: People, Society, Cultures, Meaning (in Russian). Московский педагогический государственный университет (3). ISSN 2500-2988. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Robinson, Lillian S.; Women, Stanford University Center for Research on (1 January 1990). Revealing Lives: Autobiography, Biography, and Gender. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0435-5.

- "Дурова Надежда Андреевна". www.rulex.ru.

- "Nadezhda Durova" article in Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary

- Renner-Fahey, Ona (2009). "Diary of a Devoted Child: Nadezhda Durova's self-presentation in The Cavalry Maiden". The Slavic and East European Journal. 53 (2): 189–202. ISSN 0037-6752. JSTOR 40651112. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- Vaysman, Margarita. "Nadezhda Durova: Nineteenth-Century Russian Queer Celebrity and Patriotic Icon". Torch: Oxford Center for the Humanities. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Marsh-Flores, Ann (2003). "Coming out of His Closet: Female Friendships, Amazonki and the Masquerade in the Prose of Nadezhda Durova". The Slavic and East European Journal. 47 (4): 609–630. doi:10.2307/3220248. ISSN 0037-6752. JSTOR 3220248. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- "Queerness from Prussia in 1812 to Kyrgyzstan in 2019 Meduza summarizes the latest features on LGBTQ issues in and near Russia". Meduza. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Whittle, Stephen (2 June 2010). "A brief history of transgender issues". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Karwowska, Bożena (2014). "Nadieżda Durowa i początki rosyjskiej autobiografii". Autobiografia Literatura Kultura Media (in Polish). 2: 153–162. doi:10.18276/au.2014.1.2-09 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISSN 2353-8694. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Boyarinova, Polina (25 June 2016). "Nadezhda Durova: phenomenon of gender trouble in Russia in the first half of the XIX c." Woman in Russian Society (in Russian): 57–68. doi:10.21064/WinRS.2016.2.6. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

References

- Mersereau, John Jr. & Lapeza, David (1988). Nadezhda Durova: The Cavalry Maid. Ardis.

- Barta, Peter I., "Gender Trial and Gothic Trill: Nadezhda Durova's Subversive Self-Exploration" by Amdreas Schonle in Gender and Sexuality in Russian Civilization, 2001. ISBN 0-415-27130-4

External links

- A History Net summary of Durova's life.

- A Russian culture navigator account of Durova.

- A brief excerpt from Durova's experiences during the retreat to Moscow in 1812.

- The Durov Animal Theater in Moscow, a surviving legacy of the Durov clan.

- Durova's memoir (in Russian)

- Nadezhda Durova in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary - (in Russian)

- (in Russian) Biography of Durova