Mostafa El-Nahas

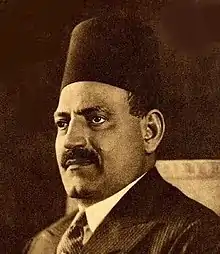

Mostafa el-Nahhas Pasha or Mostafa Nahas (Arabic: مصطفى النحاس باشا; June 15, 1879 – August 23, 1965)[1] was an Egyptian politician who served as the Prime Minister for five terms.

Mostafa el-Nahhas Pasha مصطفى النحاس باشا | |

|---|---|

| |

| 19th Prime Minister of Egypt | |

| In office March 16, 1928 – June 27, 1928 | |

| Monarch | Fuad I |

| Preceded by | Abdel Khalek Sarwat Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Mohamed Mahmoud Pasha |

| In office January 1, 1930 – June 20, 1930 | |

| Monarch | Fuad I |

| Preceded by | Adly Yakan Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ismail Sedky Pasha |

| In office May 9, 1936 – December 29, 1937 | |

| Monarch | Farouk I |

| Preceded by | Aly Maher Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Muhammad Mahmoud Pasha |

| In office February 6, 1942 – October 10, 1944 | |

| Monarch | Farouk I |

| Preceded by | Hussein Serry Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ahmed Maher Pasha |

| In office January 12, 1950 – January 27, 1952 | |

| Monarch | Farouk I |

| Preceded by | Hussein Serry Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Aly Maher Pasha |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 15, 1879 Gharbiyya, Khedivate of Egypt |

| Died | August 23, 1965 (aged 86) Alexandria, Egypt |

| Political party | Wafd Party |

Early life, education and exile

He was born in Samanud (Gharbiyya) where his father was a lumber merchant. He graduated from el-Nassereyya Elementary School in Cairo in 1891. He also graduated from the Khedivial Secondary School[2] in 1896. After earning his license from the Khedivial Law School in 1900, he worked in Mohammad Farid's law office before opening his own practice in Mansoura. In 1904 he became a judge in the Tanta National Court. He was dismissed from the bench in 1919 when he joined the Wafd as a representative of the Egyptian National Party. Exiled with Saad Zaghlul to the Seychelles in 1921-1923, Nahhas was chosen upon his repatriation to represent Samanud in the first Chamber of Deputies elected under the 1923 Constitution.

Political history

He became minister for communications in 1924. Reelected in 1926 as a deputy from Sir Abu Nanna (Gharbiyya) and barred by the British from taking another cabinet post, he was elected one of the Chamber's two vice presidents and, in 1927, its president. Upon Sa'd Zaghlul's death in August 1927, he defeated Sa'd's nephew in the contest to lead the Wafd Party.

He served as Prime Minister of Egypt in 1928, 1930, between 1936 and 1937, from 1942 until 1944, and finally between 1950 and 1952. He was prime minister for only a few months in 1928 after clashing with the king over his desire to strictly limit royal power. Nahhas married a much younger wife from a very prominent family, Zainab Hanem Elwakil, who was more than 30 years younger than he was. His wife was said to have great influence on him, and is alleged to have played a big role in spoiling the friendship between Mostafa el-Nahhas and Makram Ebeid. When the Great Palestinian Revolt of 1936-1939 started el-Nahhas pasha helped to found the Arab Higher Committee to uphold the rights of the Palestinian people. In the Abdeen Palace incident of 1942, the British ambassador Sir Miles Lampson had the Abdeen palace surrounded by British tanks, and forced King Farouk to appoint Nahas prime minister.

Nahas fell out with his patron, Makram Ebeid who was serving as the Finance minister and expelled him from the Wafd and the cabinet at the instigation of his wife.[3] Ebeid retaliated with The Black Book, a detailed expose published in the spring of 1943 listing 108 cases of major corruption involving Nahas and his wife.[3] Ebeid accused Nahas of having the Egyptian embassy in London buy expensive silver-fox fur coats for his wife with government funds; of confiscating a school in the Garden City area of Cairo to turn into his personal office; of using government money to irrigate land in the desert owned by his cousin; and of abusing his position as prime minister to pressure landowners in the Nile delta to sell farmland to him.[3] Against Madame Nahas, Ebeid accused her of engaging in insider trading on the Alexandria cotton exchange and of pressuring her husband to appoint members of her family to high offices of state that they were not qualified for.[3] Even Lampson wrote in his diary that "the so-called book does seem to contain pretty damaging evidence".[3] His wife died two years after his death in 1967. His and her cemetery are located in the Elwakil yard in Basateen, Cairo.He also helped found the Arab League in 1944.

In 1950, in a volte-face that stunned observers of Egyptian politics, Karim Thabet of King Farouk's "kitchen cabinet" arranged an alliance between the king and Nahas Pasha.[4] The U.S ambassador Jefferson Caffery reported to Washington:

"The proposal was that the King would receive Nahas in private audience prior to summoning a Wafd government and that if the King were not satisfied by his conversation with Nahas, Nahas gave his word or honor that he would retire from the leadership of the Wafd Party as an "elder statesmen" and that the King would then be free to choose any of the younger Wafd leaders in whom he had confidence. The King agreed to this proposal and was completely captivated by Nahas, who tactfully started the interview by swearing that his one desire in life was to kiss the King's hand and to remain always worthy in His Majesty's opinion of being allowed to repeat the performance. At this point Nahas went on his knees before the King who according to Thabet was so charmed that he assisted him to his feet with the words, "Rise, Mr. Prime Minister"".[4]

Caffery reported in his cable to Washington that he was appalled that Nahas, whom Caffery called the most stupid and corrupt politician in Egypt, was now prime minister.[5] Caffery stated that Nahas was unqualified to be prime minister because of his "completely total ignorance of the facts of life as they apply to the situation today", giving the example:

"Most observers are willing to concede that Nahas knows of the existence of Korea, but I have found no one who would be willing to seriously contend that he is aware of the fact that Korea borders on Red China. His ignorance is as colossal as it is appalling...At the time of my interview with Nahas he was totally unconscious of the subject which I was discussing. The only ray of light which penetrated was the fact that I wanted something from him. This prompted the street politician's response of "aidez-nous et nous vous aiderons".[5]

Caffery stated that Nahas's French (the language of the Egyptian elite) was "of dubious quality" and he spoke a colloquial Egyptian Arabic more appropriate to the streets than the high society of Cairo.[5] Caffery called Nahas a venal "street politician" whose only platform was the "tried and true formula of 'Evacuation and Unity of the Nile Valley'" and stated the only positive aspect of him as prime minister was that "we can get anything which we want from him if we are willing to pay for it".[5]

Nahas's government was extremely corrupt and in year 1951 alone Madame Nahas had acquired ownership of one thousand acres of farmland in the Nile Delta, which was ideal for growing cotton and made her into an extremely rich woman.[6] The Korean War caused a shortfall in the American cotton production as young men were called up for national service, causing a cotton boom in Egypt.[7] As the international prices for cotton rose, Egyptian landlords forced their tenant farmers to grow more cotton at the expense of food, leading to major food shortages and inflation in Egypt.[7] Nahas passed a law forbidding Egyptian farmers to grow wheat, which would done something to reduce the food shortages and the consequent inflation, as he and his wife personally benefited from the high international prices for cotton.[6]

Nahas promised in early 1951 a Five Year Plan to provide a $20 million US dollars for a universal pension system plus money for improved education, clean drinking water, and better roads, but nothing came of the plan while the corruption continued unabated.[8] He was one of the signers of the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936, but in 1951 he denounced it. In a bid for popularity amid rumors that King Farouk was planning to dismiss him, on 17 October 1951 Nahas unilaterally abrogated the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty, making himself the hero of the hour.[6] Nahas told Parliament: "It was for Egypt that I signed the 1936 treaty and it is for Egypt that I call on you to abrogate it".[6]

As the British refused to leave their base around the Suez Canal, the Egyptian government cut off the water and refused to allow food into the Suez Canal base, announced a boycott of British goods, forbade Egyptian workers to enter the base and sponsored guerrilla attacks, turning the area around the Suez Canal into a low level war zone.[9] On 24 January 1952, Egyptian guerrillas staged a fierce attack on the British forces around the Suez Canal, during which the Egyptian Auxiliary Police were observed helping the guerrillas.[10] In response, General George Erskine on 25 January sent out British tanks and infantry to surround the auxiliary police station in Ismailia and gave the policemen an hour to surrender their arms under the grounds the police were arming the guerrillas.[10] The police commander called the Interior Minister, Fouad Serageddin, Nahas's right-hand man, who was smoking cigars in his bath at the time, to ask if he should surrender or fight.[10] Serageddin ordered the police to fight "to the last man and the last bullet".[11] The resulting battle saw the police station leveled and 43 Egyptian policemen killed, together with 3 British soldiers.[11] The Ismailia incident outraged Egypt and the next day, 26 January 1952 was "Black Saturday", as the anti-British riot was known, that saw much of Downtown Cairo, which Khedive Ismail the Magnificent had rebuilt in the style of Paris, burned down.[11] Farouk blamed the Wafd for the Black Saturday riot and dismissed Nahas as prime minister the next day.[12]

After the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, the Wafd Party was dissolved. Both he and his wife were imprisoned from 1953 to 1954. He then retired to private life. His death on 23 August 1965 led to a mass demonstration at his funeral that was allowed by Gamal Abdel Nasser's government.

Honours

Egyptian national honours

| Ribbon bar | Honour |

|---|---|

| Grand Cordon of the Order of the Nile | |

| Grand Cordon of the Order of Muhammad Ali | |

| Grand Cordon of the Order of Ismail |

Foreign honors

| Ribbon bar | Country | Honour |

|---|---|---|

| Ethiopian Empire | Grand Cordon of the Order of Solomon | |

| Kingdom of Greece | Grand Commander of the Order of the Redeemer | |

| Kingdom of Italy | Grand Officier Order of the Crown of Italy | |

| Kingdom of Tunisia | Grand Cordon of the Order of Glory (Tunisia) | |

| United Kingdom | Honorary Knight Commander Order of St Michael and St George |

References

- "Muṣṭafā al-Naḥḥās Pasha | prime minister of Egypt".

- Donald M. Reid (October 1983). "Turn-of-the-Century Egyptian School Days". Comparative Education Review. 27 (3): 375. doi:10.1086/446382. S2CID 143999204.

- Stadiem 1991, p. 225.

- Stadiem 1991, p. 293.

- Stadiem 1991, p. 294.

- Stadiem 1991, p. 311.

- Stadiem 1991, p. 295.

- Stadiem 1991, p. 310-311.

- Stadiem 1991, p. 312.

- Stadiem 1991, p. 315.

- Stadiem 1991, p. 316.

- Stadiem 1991, p. 318.

Books

- Arthur Goldschmidt, Biographical Dictionary of Modern Egypt Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2000.

- Saniyya Qurra'a. Nimr al-siyasa al-misriyya Cairo, 1952.

- Christopher D. O'Sullivan. FDR and the End of Empire: The Origins of American Power in the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, ISBN 1137025247

- Laila Morsy "Farouk in British Policy" pages 193-211 from Middle Eastern Studies Volume 20, No. 4, October 1984.

- Bernard Reich, ed., Political Leaders of the Contemporary Middle East and North Africa: A Biographical Dictionary New York, 1990.

- William Stadiem Too Rich: The High Life and Tragic Death of King Farouk, New York: Carroll & Graf Pub, 1991 ISBN 0-88184-629-5.