Moshe Wallach

Moshe (Moritz) Wallach (28 December 1866[1] – 8 April 1957[2]) was a German Jewish physician and pioneering medical practitioner in Jerusalem. He was the founder of Shaarei Zedek Hospital on Jaffa Road, which he directed for 45 years.[3] He introduced modern medicine to the impoverished and disease-plagued citizenry, accepting patients of all religions and offering free medical care to indigents.[4] He was so closely identified with the hospital that it became known as "Wallach's Hospital".[1][5][6] A strictly Torah-observant Jew, he was also an activist in the Agudath Israel Orthodox Jewish movement.[7] He was buried in the small cemetery adjacent to the hospital.

Dr. Moshe Wallach | |

|---|---|

Moritz Wallach | |

Dr Wallach in 1954 | |

| Born | December 28, 1866 |

| Died | April 8, 1957 (aged 90) |

| Resting place | Shaare Zedek Cemetery, Jerusalem |

| Nationality | German |

| Years active | 1891–1947 |

| Known for | Founder and director of Shaare Zedek Hospital, Jerusalem |

| Successor | Dr. Falk Schlesinger |

| Parent(s) | Joseph Wallach Marianne Levy |

Biography

Moshe Wallach was one of seven children[4] born to Joseph Wallach (1841–1921), a textile merchant originally from Euskirchen, and Marianne Levy of Münstereifel. His parents moved to Cologne following their marriage in 1863. Joseph Wallach was a founder of Adass Jeshurun, the Cologne Orthodox community, which he later served as president.[5]

In his youth, Wallach attended the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Gymnasium, Cologne and a Jewish school run by the Cologne Orthodox community.[1] He studied medicine at the University of Berlin and University of Würzburg, and received his Doctor of Medicine degree in 1889.[1][5] In 1890 he was chosen by the Frankfurt-based Jewish Conference for the Support of the Jews in Palestine to emigrate to Palestine and carry out its plans to open a modern Jewish hospital in Jerusalem.[8] Wallach first opened a clinic and pharmacy in the Armenian Quarter of the Old City.[9][10][11] He also worked in the Bikur Holim Hospital as a women's and children's physician, ophthalmologist, and surgeon specializing in neck surgery.[5] He was the first to perform tracheotomies in Jerusalem,[12][13] and performed many ritual circumcisions.[10][14]

In 1896[1] Wallach returned to Europe to raise funds for the new hospital, collecting donations in Germany and Holland.[14] Upon his return to Jerusalem, he purchased a 10-dunam (2.5 acre) plot of land located 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) outside the Old City Walls on what would become Jaffa Road.[4] He registered the land in his own name with the help of the German consul in Jerusalem, Dr. Paul von Tischendorf, who also helped him procure building materials from Germany.[11][15]

Shaare Zedek Hospital opened on January 27, 1902[16] with 20 beds, an outpatient clinic, and a pharmacy.[17] With most of the hospital's patients living in the Old City, a 20-minute donkey ride away,[5][16] and a dearth of in-house staff, Wallach often made house calls to determine whether a case actually warranted hospitalization. If transporting to the hospital would be dangerous, he performed curettage; otherwise, he accompanied the patient on a stretcher back to the hospital surgery.[14]

In addition to departments for internal medicine, maternity and children,[4] Wallach later opened an infectious diseases department which was the only one in Jerusalem to treat polio.[18] During the milk shortages of World War I, Wallach bought several milk cows and built a cowshed and grazing field for them behind the hospital.[5][16] The herd was gradually increased to 40 cows[19] and became a source of revenue, especially for kosher-certified milk sales for Passover.[12]

Wallach, who for several decades was the only in-house physician at Shaare Zedek,[14] ran the hospital as a strictly Orthodox institution. He insisted on strict Sabbath observance and a high level of kashrut in the hospital,[17] and personally supervised the milking of the cows.[4] He arranged for an electric generator to service the hospital so that it would not have to rely on electricity provided by the power station, where Jews worked on Shabbat.[20] He set aside part of the field adjacent to the hospital to the growing of wheat for shemura matzo and supervised the baking of matzos for Passover. For Sukkot, he erected a 10 metres (33 ft) by 4 metres (13 ft) sukkah in the hospital courtyard to accommodate both eating and sleeping.[21]

The language of the hospital was German or Yiddish; Wallach refused to speak in Hebrew, the language of Torah study, in a secular institution.[14] Before the rise of Nazism, Wallach ordered all hospital correspondence to be conducted in German; afterwards he allowed letters to be written in Rashi script, a Hebrew typeface.[5][22]

Schwester Selma

Wallach opened the hospital with two trained nurses, Schwester (Nurse) Stybel and Schwester Van Gelder.[4] Van Gelder returned to her native Holland early on, being dissatisfied with the "primitive conditions" that existed at Shaare Zedek.[14] Stybel fled to Germany with the outbreak of World War I; when she returned, she organized a strike against the conditions at the hospital. Wallach did not respond to her demands, and when she was unable to find other work and asked for her job back, he made her head of the laundry. "A true nurse never abandons her patients", he told her.[4]

In dire need of a head nurse, Wallach traveled to Europe in 1916. He was impressed with the similar organizational structure of the Jewish Hospital in Hamburg, and asked the head nurse there if she could spare one of her staff. The 32-year-old Selma Mayer (1884–1984), who in 1913 had been one of the first Jewish nurses to receive a German State Diploma, was recommended and agreed to travel.[14] She arrived at Shaare Zedek in December 1916[14] and worked and lived at the hospital for the next 68 years, until her death at the age of 100.[16][23]

Schwester Selma was Wallach's right-hand person in the running of the hospital. She accompanied him on house calls and stood in for him as hospital director when he was away.[14][23] She applied the German system to running the wards[14] and cultivated a spirit of warm, personalized patient care that became the modus operandi for the hospital to this day.[12]

Jerusalem personality

Wallach became a well-known and respected personality in Jerusalem. He was invited to every political and diplomatic reception that took place during the Ottoman and British Mandate periods. The British Governor of Jerusalem Ronald Storrs was a personal friend of Wallach's; he expedited the doctor's request for the annual delivery of matzos to the hospital for the Passover holiday. Wallach was also close to leaders of the Old Yishuv, including Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld. He was a personal friend of Rabbi Jacob Israël de Haan, a political spokesman for the Haredi community in Jerusalem who was assassinated in 1924 just outside Shaare Zedek Hospital as he was returning to the hospital synagogue for evening prayers.[15]

Wallach was the personal physician of many Torah leaders of the Old Yishuv, among them Rabbi Chaim Hezekiah Medini (the Sdei Chemed), whom he treated in Hebron,[24] Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, Rav of Jerusalem,[8] Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky, the first Dushinsky Rebbe,[25] and Rabbi Solomon Eliezer Alfandari, who lived in the Ruchama neighborhood (today Mekor Baruch).[26] He also treated King Abdullah I of Jordan.[8]

Another Torah Leader whom Wallach had the merit to treat was the Previous Lubavitcher Rebbe, [Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn]. The Rebbe writes in a letter dated 21 Elul 5689 (= 26 September 1929), "When the saddenning news of the pogroms in Israel (Hebron Massacre) (may it be rebuilt and reestablished speedily in our days amen) reached me, travelling from Alexandria to Trieste, Sunday, week of Torah Portion "Eikev" [= August 18 in 1929] I became sick with a sickness of the kidneys as a result of the great grief and aggravation, and thank G-d, the precious, wise, well known, truly G-d fearing, Dr. Wallach (may he live), was together with me, and applied treatments to alleviate my aches..."[27] The Rebbe had suffered a kidney attack, and Wallach was aboard and treated him and cared for him until he regained his strength. Soon after, he approached Rabbi Schneersohn to request a manner of penance ("kapparah"). When asked for what, he replied, "since the Rebbe, a Jewish leader, needed by many, must be in full health, it would be impossible for him to become unwell (i.e. God would not allow such a thing) if not for the presence of a doctor in which case he would not have access to the necessary medical care. If so, my presence aboard the ship, made it possible for the Rebbe to experience pain." The Rebbe recounted this incident to his son-in-law, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who in turn recounted it in a public talk in 1987, as an example of true humility and contriteness.[28]

Personal

Wallach was a dedicated physician and a demanding and exacting employer.[14][29] He was known to shout at nurses and patients alike who did not follow his instructions to the letter.[4] His first pharmacist quit because he was unable to tolerate Wallach's behavior.[30] However, Wallach also had a sense of humor. Once he was leaving the hospital late at night when he encountered a woman waiting by the locked gate. She did not know who he was, but begged him to let her in for a few minutes to see her husband, who had had an operation the previous day. "Quick, before that crazy man Wallach comes", she said. Dr. Wallach let her in, and received her profuse thanks when she came out again. "What is your name?" she asked. "You are such a kind person". "I am the crazy man Wallach", he replied.[31][14][32]

Despite his outer gruffness, Wallach had a kind heart. He adopted a young Syrian girl named Bolissa who had been brought to the hospital by her father and was subsequently abandoned there.[14][15] He personally assisted poverty-stricken immigrants to find housing and jobs,[3] and did not charge indigent patients.[4] Before World War I, he intervened with Jamal Pasha, Ottoman leader in Palestine, on behalf of Jews who had been conscripted into the Turkish army or who were in danger of being expelled from the country.[33] He also helped members of his extended family in Germany immigrate to Palestine after the rise of Nazism in the 1930s.[34]

Wallach was scrupulous in his own mitzvah observance.[11] He engaged a teacher to study Talmud with him and spent much time learning with Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, leader of the Old Yishuv.[35] Whenever he traveled on house calls, he brought along a Book of Psalms to recite on the road.[21]

Wallach never married. A wealthy German donor to the hospital, Yehoshua Hearn, wanted him to return to Germany to marry his daughter, but after consultation with Rabbi Sonnenfeld, Wallach determined that he would not leave the land for any reason. Later, when the girl agreed to travel to Palestine, Wallach arranged a shidduch between her and his brother Ludwig, who worked as a clerk at Shaare Zedek Hospital.[15][36] Wallach resided in rooms in the hospital until his final day.[12][8][15]

Final years and legacy

Wallach retired at the age of 80. He was succeeded as director of Shaare Zedek by Dr. Falk Schlesinger, another German-Jewish physician.[14]

Wallach was feted on several occasions, beginning with a seventy-fifth birthday celebration at a hotel, which was attended by British Mandate health officials.[14] Before his eightieth birthday, a Torah scroll was commissioned in his honor. Upon its completion three years later, Wallach donated it to the hospital synagogue.[37] Two banquets were held in honor of his eighty-fifth birthday – one in the hospital, attended by the Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel, Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel, the Minister of Health, representatives of the Doctors Union, and representatives of the Old and New Yishuvs; and the second in the office of the Jerusalem mayor, Shlomo Zalman Shragai, who bestowed a commendation on Dr. Wallach for his years of public service.[38] In honor of his ninetieth birthday, Wallach was awarded an honorary degree from the medical faculty of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The city of Jerusalem also named him a Yakir Yerushalayim (Worthy of Jerusalem); however, Wallach died the day before the presentation ceremony took place.[5]

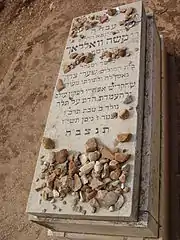

Wallach died on April 8, 1957, at the age of 90. He was buried in the small cemetery adjacent to the hospital, on land he had given to the burial society of the Perushim and Ashkenazim of Jerusalem to use as a temporary burial ground during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.[39] After the war, most of the 200 graves in this cemetery were relocated to permanent cemeteries, but a handful of graves remained, including that of Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky, the first Dushinsky Rebbe, who died in Shaare Zedek Hospital in 1948.[25] Per his request, Wallach was buried beside the Dushinsky Rebbe, whom he considered his mentor.[2][6][14]

According to Schwester Selma, over half of Jerusalem attended Wallach's funeral.[14] He was eulogized by Who's Who in Israel as the Israeli medical profession's "spiritual leader for two generations".[40] The Jerusalem municipality named the small street west of Shaare Zedek Hospital "Moshe Wallach Street" in his honor.

Prime Minister of Israel Yitzhak Rabin paid tribute to Wallach in a 1995 address in the United States Capitol rotunda inaugurating the Jerusalem 3000 celebrations. In a speech titled "My Jerusalem", Rabin began:

"Jerusalem has a thousand faces – and each one of us has his own Jerusalem. My Jerusalem is Dr. Moshe Wallach of Germany, the doctor of the sick of Israel and Jerusalem, who built Sha'arei Zedek hospital and had his home in its courtyard so as to be close to his patients day and night. I was born in his hospital. I am a Jerusalemite".[41]

References

- Tidhar, David (1947). "Dr. Moshe Wallach" ד"ר משה ואלאך. Encyclopedia of the Founders and Builders of Israel (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Estate of David Tidhar and Touro College Libraries. p. 429.

- Rossoff (2005), p. 383.

- Navot, O (June 2003). "Dr. Moritz Wallach – A century of medicine and tradition in Shaare Zedek (Abstract)". Harefuah. 142 (6): 471–4, 483. PMID 12858837.

- Shapiro, Sraya (28 January 1996). "The Pedantic 'Herr Doktor'". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 10 June 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2012. (subscription)

- Arntz, Hans-Dieter (14 February 2008). "Ein jüdischer Arzt als Pionier in Erez Israel: Dr. Moshe Wallach aus Köln gründet das Shaare Zedek Hospital in Jerusalem" [A Jewish Doctor as a Pioneer in Eretz Israel: Dr. Moshe Wallach from Cologne founded the Shaare Zedek Hospital in Jerusalem] (in German). hans-dieter-arntz.de. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Rossoff (2001), p. 489.

- Ben Shlomo, Yosef. "A Dedicated and Devout Doctor of Jerusalem". shemayisrael.co.il. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Mizrahi, Rabbi Moshe. "Profile: Dr. Moshe Wallach, z"l, Found of Shaare Zedek Hospital". Hamodia Magazine, April 23, 2015, pp. 10-11.

- "Mayor Giuliani Proclaims 'Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem Day': Salutes 1998 Golden Jubilee Mission". Mayor's Press Office. 23 June 1997. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Porush (1963), p. 24.

- Shimony, Yisca (27 June 2001). "Voyage into Yesteryear – How Shaarei Zedek was established". Dei'ah VeDibur. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- לתולדות בתי החולים היהודיים בירושלים [Annals of the Jewish Hospitals in Jerusalem] (in Hebrew). medethics.org. 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Porush (1952), p. 9.

- Schwester Selma (1973). "My Life and Experiences at 'Shaare Zedek'". Shaare Zedek Medical Center. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2012. (translated from the German)

- על שולחן העבודה של הדוקטור [On the Doctor's Desk]. Et-Mol (in Hebrew). Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (194). July 2007.

- Eylon, Lili (2012). "Jerusalem: Architecture in the late Ottoman Period". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Porush (1952), p. 19.

- Porush (1952), p. 50.

- Porush (1952), p. 23.

- Porush (1952), p. 45.

- Porush (1952), p. 26.

- Porush (1952), p. 52.

- Bartal, Nira (1 March 2009). "Selma Mair, 1884–1984". Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- זכרונות (ב): הרב ד"ר משה אויערבך זצ"ל [Memoirs (2): Rabbi Dr. Moshe Auerbach, zt"l] (PDF). HaMaayan (in Hebrew). Jerusalem. 21 (4): 11. 1981.

- Rossoff (2005), p. 386.

- Sofer, D. "Rav Shlomo Eliezer Alfandari". Yated Ne'eman. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- https://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=31602&st=&pgnum=267, in hebrew and translated here for the first time

- https://www.sie.org/templates/sie/article_cdo/aid/2508083/jewish/Shabbos-Parshas-Vayakhel-Pekudei-Parshas-HaChodesh-Mevarchim-HaChodesh-Nissan-5747-1987.htm, end of web page

- Porush (1963), p. 52.

- Porush (1952), p. 20.

- "Dedicated and Devout Doctor of Jerusalem". shemayisrael.co.il. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Rossoff (2001), pp. 485–486.

- Porush (1963), p. 50.

- "Ruth Wallach". Spurensuche. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Porush (1952), p. 11.

- Porush (1952), p. 10.

- Porush (1952), p. 31.

- Porush (1952), p. 32.

- Samsonowitz, M. (16 October 2002). "Burial in Jerusalem: The Har Menuchos Cemetery – Part I". Dei'ah VeDibur. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Who's Who in Israel 1958. P. Mamut. 1961. p. 2.

- "My Jerusalem" (PDF). Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

Sources

- Porush, Eliyahu (1952). "Shaare Zedek: Concerning the History of Sha'arei Tzedek Hospital in Jerusalem and its Physician and First Chief Administrator, Dr. Moshe Wallach". Solomon Press. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Porush, Eliyahu (1963). "Early Memories: Recollections concerning the Old Yishuv in the Old City and its environs during the last century". Solomon Press, Jerusalem. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Rossoff, Dovid (2005). קדושים אשר בארץ: קברי צדיקים בירושלים ובני ברק [The Holy Ones in the Earth: Graves of Tzaddikim in Jerusalem and Bnei Brak] (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Machon Otzar HaTorah.

- Rossoff, Dovid (2001). Where Heaven Touches Earth: Jewish Life in Jerusalem from Medieval Times to the Present. Feldheim Publishers. ISBN 0873068793.