Morphology (architecture and engineering)

Morphology in architecture is the study of the evolution of form within the built environment. Often used in reference to a particular vernacular language of building, this concept describes changes in the formal syntax of buildings and cities as their relationship to people evolves and changes. Often morphology describes processes, such as in the evolution of a design concept from first conception to production, but can also be understood as the categorical study in the change of buildings and their use from a historical perspective. Similar to genres of music, morphology concertizes 'movements' and arrives at definitions of architectural 'styles' or typologies. Paradoxically morphology can also be understood to be the qualities of a built space which are style-less or irreducible in quality.

Some ideological influences on morphology which are usually cultural or philosophical in origin include: Indigenous architecture, Classical architecture, Baroque architecture, Modernism, Postmodernism, Deconstructionism, Brutalism, and Futurism. Recent contemporary advances in analytic and cross platform tools such as 3d printing, virtual reality, and building information modeling make the current contemporary typology formally difficult to pinpoint into one holistic definition. Advances in the study of Architectural (formal) morphology have the potential to influence or foster new fields of study in the realms of the arts, cognitive science, psychology, behavioral science, neurology, mapping, linguistics, and other as yet unknown cultural spatial practices or studies based upon social and environmental knowledge games.[1] Often architectural morphologies are reflexive or indicative of political influences of their time and perhaps more importantly, place. Other influences on the morphological form of the urban environment include architects, builders, developers, and the social demographic of the particular location[2]

Urban morphology provides an understanding of the form, establishment and reshaping processes, spatial structure and character of human settlements through an analysis of historical development processes and the constituent parts that compose settlements. Urban morphology is used as a method of determining transformation processes of urban fabrics by which buildings (both residential and commercial), architects, streets and monuments act as elements of a multidimensional form in a dynamic relationship where built structures shape and are shaped by the open space around them.[3] Urban places act as evolutionary open systems that are continually shaped and transformed by social and political events and by the market forces.[4]

History

Urban morphology as an organised scientific study began formally in the 19th century[3] due to the expansion of reliable topographic maps and reproducible plans.[5] However, architecture has existed far longer, with the first surviving written work on the subject known as De architectura, written by Roman architect and engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio between 30 and 15 BCE.[6] Here, Vitruvius detailed the three principals of architecture firmitas, utilitas, venustas. Translated to modern English as durability, utility and beauty. Archaeologists have studied the ruins of ancient cities such as Mesopotamia, Egypt and Minoan to show evidence that urban planning dates back to the Bronze Age, through visible patterns of paved streets lined in right angles. Originally, town planning was used as a mechanism for armed defence. The decline of the Roman Empire in 395 AD saw cities in Europe expand incoherently without formal urban planning. The Renaissance era saw urban hubs expand with enlarged extensions to allow for advancements that took place during the industrial age. It was then that urban planning became a formalised study, used to allow citizens with healthier working conditions.

Theory

The theory of morphology extends many different disciplines including architectural theory branching from the philosophy of art, engineering, linguistics, culture and sociology.[7]

However, advances in information technology, the development of a globalised 24-hour economy through the three leading world cities New York, London and Tokyo and their smaller counterparts have profoundly influenced the world's urban systems.[8] Currently, there is more than 300 metropolitan regions that house more than one million people and through steadily global population increases metropolitan regions will continue to increase in size.[9] The global trend towards rapid urbanisation is outlined by the global urban population being 34% of the world's total in 1960, 43% in 1990 and 54% in 2014, with projections expected to reach 66% by 2050.[10] Rapid urbanisation commonly causes challenges within urban places, for example, traffic jams, high cost of living, lack of green space, biodiversity loss, air pollution and other anthropogenic environmental effects.[11] As a result, urban planners, geographers and architects have put forth numerous theoretical models with aim to improve understanding upon the functionality, aesthetic nature and environmental sustainability.[11] However, it is widely accepted that there are four theoretical explanations to the morphological pattern of a city.

Concentric Zone Model

Although many models have been developed in geography and urban planning fields, encompassing assorted complexities one which holds its widely used and early status is the concentric zone model.[12] The concentric Zone Model provided a stylized description of the urban form, derived from Ernest Burgess's 1920's idea: the bid-rent curve. This implicated that the core central zone of a city becomes used as the Central Business District, then surrounded in turn by a zone of transition between areas of profession and that of working-class suburbs.[13] This is then followed by middle-class suburbs, and finally situated on the outside ring of the city is a zone of commuters. Opposers have argued that this is a normative model that presents an idealistic and only hypothetical model of a city, when in fact current land use is a part of a more complicated three-dimensional system.[14]

This model led to the acceptance of modern-day terms such as “inner city” and the “suburban ring”. [15]

- The development of Burgess’ theory stemmed from three main assumptions upon the pattern and morphological structure of urban growth: [16]

- The linear progression of society moves from traditional to modern which brings forth the changing construction of social relations

- An individual's agency-based approach to the urban processes without structural constraints which explains the urban condition

- The concept of the city as a unified “whole”[16]

Sectoral model

The Sectoral Model, proposed by economist Homer Hoyt in 1939, explores the notion that the development of cities is centralised around transportation lines where wedges of residential land is concentrated by social class. Although, this model acts as a highly generalised theory does not equally represent urban morphologies of the developing world. Leaders in the field state that the twenty first century global economy's tendency towards capital reduces the demand for labour and in turn causing growing unemployment.[15] This leads to the notion that innovations in transport play a significant role in the accessibility of city's surface.[15] For example, the wide implementation of suburban railway networks and motor buses were expected to have proportionately impact the higher increases in periphery land prices. Contrastingly, it is expected that in periods of low innovation within the transport sector land values would have been proportionately higher closer to the city centre.[15] Although, opposers to this theory suggest that the fact that transport innovations are typically closely associated with increases in building and development activity which in itself is known to raise land values and thus, it is difficult to assess the relative strengths and underlying influences.[17] Thus, the commercial, industrial and residential components within the urban this model's land-use pattern are susceptible to the locational analysis and their attempt to maximise profits by substituting higher rent for increased transport costs from the city centre and vice versa.[17] This acts as an alternative model to the ‘original’ urban morphology model by Burgess with proposed a city as a concentric being which adequately kept each land use activity within its proposed circle. However, in reality it is often the addition of varying transport options within differing locations that allow for the formation of individual sectors for each land use task.[17]

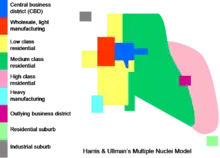

Multiple Nuclei Model

This model developed by Harris and Ullman in their 1945 book “The Nature of Cities”[18] further expands on previous morphological theories to provide a model which encompasses the issues that arise over large territorial expanse and growing population. Where previous theories have provided the idea that a city must only have one Central Business District (CBD), the Multiple Nuclei Model has more than one CBD. Rather, this model postulates that there are a number of different growth nuclei, each of which influences the distribution of people, activities and land uses within the area.[19] Each nucleus is a highly specialised subset of the city's urban form and activities as each area is marketed to the demographic within the area from retail, manufacturing, education, health and residential areas.[19] Thus, allows for highly diversified economic functions over an extensive geographical area. This forms a kind of urban mosaic in which the city's spatial geometry is made up of differing nuclei that are no longer organised around a single centre, where the CBD still acts as a functional and important nucleus to the city. One popular weakness to the multiple nuclei model is the premise that distinctions and boundaries between nuclei zones are distinct borders, however this is largely unheard of practically.[20] This model requires the use of four basic principles:[19]

- Certain activities require specialised facilities located in only one or a few sections of the metropolis. For example, manufacturing areas requiring large blocks of undeveloped land located near rail lines.

- Certain like activities profit from adjacent congregation, as seen in the clustering of retail establishments into malls and shopping centres

- Certain unlike activities are antagonistic or detrimental to each other, as seen in the case of manufacturing plants and upper-class residential developments.

- Certain activities are unable to afford the costs of the most desirable locations, as seen in the case of low-income residential areas and high land with a much sought-after view.[19]

One real-world example of this model is the multiple nuclei form of New York City, New York. The cluster of high-end retail institutions within the city deemed the naming of New York's “diamond district” which is one specialised subset of the city's economy and function.[21]

Agents of Morphology

It is argued that urban structure develops irrespective of its objective development by legalisation from government of developers which attempt to control the shape of urban structure.[22] Each agent within the urban landscape – developers, architects, builders, urban planners, and politicians – attempt to pursue their own goals for both the functional and aesthetic qualities of land use. Initially, the occurrence of an action of change is proceeded by a developer.

Advancements

It has been proven that a significant challenge of the twenty first century will be to establish effective links between urban morphologies, efficiency and resilience of urban place in the future. Urban resilience refers to the ability of an urban place to adapt, grow and evolve when it is placed under stress events. Most climate scientists agree that warmer Earth surface temperatures increase the frequency and severity of natural disasters, with these events becoming 5 times as common in recent years.[23] With this, urban microclimates have endured extreme changes, largely due to the combination of global warming and rapid urbanisation.[24] It is known that nearly a quarter of the world's population resides in areas where heat exposure us rising dramatically, in some cases to the point where habitability is questioned.[23] Thus, in order to maintain environmental sustainability into the future adaption to housing and the wider urban fabric is deemed essential. One method for this is the restricting of housing using advancements in engineering to provide innovation and increase the suitability of architecture.

References

- Thompson, William (2013). The Morphological Construct in, Architectural Technology Research and Practice, ed Emmitt S. oxford: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. pp. 47/62. ISBN 9781118292068.

- Oliveira, Vitor. “The Agents and Processes of Urban Transformation.” Urban Morphology An Introduction to the Study of the Physical Form of Cities 31-45 Endnote.com, 2021. https://click.endnote.com/viewer?doi=10.1007%2F978-3-319-320830_3&token=WzM2NDQ5MzcsIjEwLjEwMDcvOTc4LTMtMzE5LTMyMDgzLTBfMyJd.uAdOb7dzuiF470le8NfjqjLZzIw.

- Mandal, Koushik; Chatterjee, Soumendu; Das Chatterjee, Nilanjana (2018-05-22). "MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF A HISTORICAL URBAN LANDSCAPE: THE CASE OF CONTAI, AN EARLY URBAN CENTRE OF EASTERN INDIA".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Salat, Serge (2014). "BREAKING SYMMETRIES AND EMERGING SCALING URBAN STRUCTURES A Morphological Tale of 3 Cities: Paris, New York and Barcelona" (PDF). International Journal of Architectural Research.

- Gauthiez, Bernard (2004). "The history of urban morphology" (PDF). Urban Morphology. 2: 71–89. doi:10.51347/jum.v8i2.3910. S2CID 252361510.

- "Marcus Vitruvius Pollio Biography - Infos for Sellers and Buyers". www.vitruvius-pollio.com. Retrieved 2022-05-13.

- Gauthier, Pierre (2006). "Mapping Urban Morphology: A Classification Scheme for Interpreting Contributions to the Study of Urban Form" (PDF). Geography Publications.

- Tian, Guangjin; Wu, Jianguo; Yang, Zhifeng (2010-04-01). "Spatial pattern of urban functions in the Beijing metropolitan region". Habitat International. 34 (2): 249–255. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.09.010. ISSN 0197-3975.

- Wu, Jianguo (Jingle) (2008-01-01). "Making the Case for Landscape Ecology An Effective Approach to Urban Sustainability". Landscape Journal. 27 (1): 41–50. doi:10.3368/lj.27.1.41. ISSN 0277-2426. S2CID 14581050.

- Bodo, Tombari (2019). "Rapid Urbanisation: Theories, Causes, Consequences and Coping Strategies". Annals of Geographical Studies. 2.

- Tian, Guangjin; Wu, Jianguo; Yang, Zhifeng (2010-04-01). "Spatial pattern of urban functions in the Beijing metropolitan region". Habitat International. 34 (2): 249–255. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.09.010. ISSN 0197-3975.

- Tian, Guangjin; Wu, Jianguo; Yang, Zhifeng (2010-04-01). "Spatial pattern of urban functions in the Beijing metropolitan region". Habitat International. 34 (2): 249–255. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.09.010. ISSN 0197-3975.

- Rogers, Alisdair; Castree, Noel; Kitchin, Rob (2013-09-19), "concentric zone models", A Dictionary of Human Geography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199599868.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-959986-8, retrieved 2022-05-25

- Ford, Larry (1974). "METROPOLITAN EVOLUTION, URBAN IMAGES, AND THE CONCENTRIC ZONE MODEL" (PDF). Urban Eras and the Cityscape.

- CURRIE, LAUCHLIN (1974-01-01). "The "Leading Sector" Model of Growth in Developing Countries". Journal of Economic Studies. 1 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1108/eb008033. ISSN 0144-3585.

- <chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203543047-3/introduction-part-one-nicholas-fyfe-judith-kenny> "eResources, The University of Sydney Library". login.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au. doi:10.4324/9780203543047-3. S2CID 219084012. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- Whitehand, J. W. R. (1972). "Building Cycles and the Spatial Pattern of Urban Growth". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers (56): 39–55. doi:10.2307/621541. ISSN 0020-2754. JSTOR 621541.

- Harris, Chauncy D.; Ullman, Edward L. (November 1945). "The Nature of Cities". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 242 (1): 7–17. doi:10.1177/000271624524200103. ISSN 0002-7162. S2CID 145689475.

- Schwirian, Kent (2007-02-15), "Ecological Models of Urban Form: Concentric Zone Model, the Sector Model, and the Multiple Nuclei Model", in Ritzer, George (ed.), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. wbeose004, doi:10.1002/9781405165518.wbeose004, ISBN 978-1-4051-2433-1, retrieved 2022-05-31

- "What are the criticisms of the multiple nuclei model? – Gzipwtf.com". Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- Holt, Alison R.; Mears, Meghann; Maltby, Lorraine; Warren, Philip (December 2015). "Understanding spatial patterns in the production of multiple urban ecosystem services". Ecosystem services. 16: 33–46. doi:10.1016/J.ECOSER.2015.08.007. ISSN 2212-0416. Wikidata Q61988003.

- Stojanović, Velimir (2015). "CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES OF THE CYCLE OF CHANGES IN URBAN MORPHOLOGY: URBAN THEORY AND PRACTICE" (PDF). The Creativity Game.

- McDaniel, Eric (2021-09-07). "Weather Disasters Have Become 5 Times As Common, Thanks In Part To Climate Change". NPR. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- Guo, Andong; Yang, Jun; Sun, Wei; Xiao, Xiangming; Xia Cecilia, Jianhong; Jin, Cui; Li, Xueming (2020-12-01). "Impact of urban morphology and landscape characteristics on spatiotemporal heterogeneity of land surface temperature". Sustainable Cities and Society. 63: 102443. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2020.102443. ISSN 2210-6707. S2CID 224951296.