Mornos

The Mornos (Greek: Μόρνος) is a river in Phocis and Aetolia-Acarnania in Greece. It is 70 km (43 mi) long.[1] Its source is in the southwestern part of the Oiti mountains, near the village Mavrolithari, Phocis. It flows towards the south, and enters the Mornos Reservoir near the village Lefkaditi. The dam was completed in 1979.[2] It leaves the reservoir towards the west, near Perivoli. The river continues through a deep, sparsely populated valley, and turns south near Trikorfo. The lower course of the Mornos forms the boundary between Phocis and Aetolia-Acarnania. The Mornos empties into the Gulf of Corinth about 3 km southeast of Nafpaktos.

| Mornos | |

|---|---|

Mornos river | |

| Location | |

| Country | Greece |

| Region | Phocis and Aetolia-Acarnania |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Oiti mountains |

| Mouth | |

• location | Gulf of Corinth |

• coordinates | 38°22′28″N 21°51′12″E |

| Length | 70 km (43 mi) |

Geology of the Mornos rift valley

The Mornos river erodes the Mornos rift valley, which crosses the trough between Parnassos and Pindus geotectonic zones.[3] Those zones are simply mountain chains trending generally NW to SE. They were formed during the Hellenic orogeny, when the mountain zones of Greece were thrust upward in folds due to compression caused by the subduction of the African Plate under the Eurasian Plate. The old subduction zone remains as the Hellenic trench. The zones closest to the subduction are the outer Hellenides, where Hellenides is the geologic term for the mountains of Greece. The inner Hellenides are further east.

Some compression continues today. However, in the Miocene (23-5 Ma) another geologic regime began, the extensional, as part of a process called back-arc extension. In this regime, not yet totally understood, the overriding plate behind the arc raised by the subduction, termed the "back arc," began to extend itself, pushing the arc, here the Hellenic arc, back over the subduction, causing what is known as "slab-rollback," in which the actual line of subduction moves in a direction opposite to the subduction even while the latter is still subducting and compressing. This extension in the back-arc region, causing normal faults, even while reverse faults are still collecting in the compression zone, opened the Aegean Sea starting in the Miocene, and the Corinth rift along the Corinth fault, a normal one, starting less than 2 Ma in the Pleistocene (5-3 Ma).[4]

As a result of this "pull-apart" stress across the outer Hellenides, the Gulf of Corinth and its extension on the west, the Gulf of Patras, divided the Peloponnesus from the mainland and moved it south. The seismic zone created by all this deformation is one of the most intense on Earth. In addition to causing the main fault, the stress of extension relieved itself over a number of smaller approximately parallel subfaults within the Corinth Basin and to the north of it. One of these is the Amphissa-Arachova fault system, containing the Delphi fault, and creating the Pleistos rift valley. Further west is the Mornos fault, creating the Mornos rift valley, still separated from the valley to the east by mountains of the outer Hellenides.

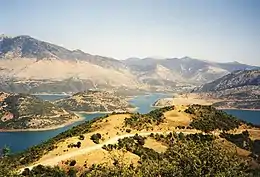

Mornos artificial lake

Mornos Lake was created as a reservoir for the city of Athens, which is populated by about 3.1 million people, representing about 40% of the population of Greece. To create it, a simple earthen embankment was placed across the Mornos River in Central Greece at 38°31′37.1″N 22°07′14.7″E. Though of earth, the soil is very compact. Monitored by GPS, the dam has a low rate of deformation and is considered one of the more stable in Greece. The fact that the dam is located in a region of high seismicity causes some concern and results in a higher level of monitoring.[5]

Mornos aqueduct

The Mornos aqueduct is the sole conduit of water extending the entire distance from the reservoir to the processing stations of north Attica. That distance is 110 kilometres (68 mi), which is not exactly straight, but curves generally to the south and is positioned to take best advantage of the terrain. Because of the mountains, an aqueduct of this magnitude was impossible to ancient engineers, who constructed many effective aqueducts marvelous for their times. some of which stand partially yet. What the moderns have that the ancients did not are the modern methods of tunneling. The aqueduct runs through 15 tunnels for a distance of 71 kilometres (44 mi). Due to modern tunneling machines and laser measurement devices no mountain is beyond the capability of the engineers.

The method of transport is still gravity feed, the cheapest and most reliable in case of disaster. There is no need now for arched aerial structures porting water across valleys. Modern conduits go underground through steel and concrete structures far below the valley. For example, the Mornos aqueduct crosses the Pleistos valley at Delphi, but none of it is observable to the visitor, as it is deep underground. It was thought more practical to place the tunnel below the karst imperfections near the surface, as their irregularities would place variable stresses on the structure, facilitating topical wear and tear and creating ruptures.

Places along the river

See also

Footnotes

References

- Greece in Figures January - March 2018, p. 12

- ΕΥΔΑΠ Archived 2013-04-13 at the Wayback Machine (in Greek)

- Karymbalis 2007, p. 1451, Figure 2

- Moretti 2003, pp. 325–326

- Gikas, Vassilis; et al. (2005). Deformation Studies of the Dam of Mornos Artificial Lake via Analysis of Geodetic Data (Report). Cairo: FIG Working Week 2005 and 8th International Conference on the Global Spatial Data Infrastructure (GSDI-8).

Reference bibliography

- Karymbalis, E.; et al. (2007). "Recent Geomorphic Evolution of the Fan Delta of the Mornos River, Greece: Natural Processes and Human Impacts". Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece. Proceedings of the 11th International Congress, Athens, May 2007. XXXX.

- Moretti, Isabelle; et al. (2003). "The Gulf of Corinth: an active half graben?". Journal of Geodynamics. 36 (1–2).