Monjeríos

Monjeríos were gendered quarters within a colonial Spanish mission for overseeing, regulating, and disciplining unmarried Indigenous girls and single women.[1][2] Girls were taken away from their parents to the monjeríos at around the age of seven until marriage.[1][3] The quarters functioned as a form of social control at the missions for conversion to Catholicism, regulation of the sexuality of girls and women, and for the rearing of Indigenous children as a labor source.[1][4]

The monjeríos instituted family separation on Indigenous peoples, with reports of sexual abuse.[5] Resistance and rebellions toward the monjeríos occurred.[5] There were monjeríos at all of the Spanish missions in California, often multiple at a single site.[1] There were similar quarters for Indigenous boys and single men known as jayuntes.[1] The monjeríos were not disbanded until the secularization of the missions by the First Mexican Republic in 1834.[5]

Construction

Locations

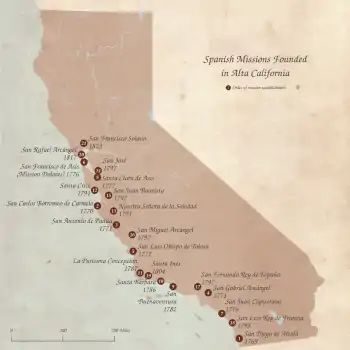

Monjeríos were constructed at all of the twenty-one Spanish missions in Alta California established along the California coastline along the El Camino Real.[1] There were also monjeríos constructed elsewhere, including at Mission Santo Tomás in present-day Baja California.[6]

Priority

The monjerío was often one of the first rooms constructed in the establishment of the missions.[1] They were deemed high priority and frequently built in the first five years of the mission's establishment.[1] The missionaries put their importance above many other facilities, since it often took 20 to 30 years to complete all of the buildings of the mission.[1]

Design

Monjeríos commonly had walls that were three to four feet thick and bars on the high windows,[1] if they had windows at all.[5] Having windows near the ceilings reduced communication between people within the interior and people on the outside.[1] The rooms were often built in areas that could be easily watched by the mission fathers, with doors that opened to the mission's central courtyard, adjacent or across from the quarters of the missionaries.[1]

Restricting movement and communication and maximizing surveillance were integral to the design of monjeríos within the Mission complex.[5] Only a few monjeríos were constructed with a different design or placement, such as the one located at Mission La Purisma Concepcion in modern-day Lompoc, California.[1]

Conditions

The way in which monjeríos were constructed along with their upkeep by the missionaries led to poor conditions within the rooms themselves. Missionaries themselves often described the monjeríos as benign institutions.[5] However, other colonial officials contradicted this framing of the conditions of the monjeríos. The seventh governor of Las Californias Diego de Borica described them as "small, poorly ventilated, and infested,"[7] further noting that the confinement also contributed to an unbearable stench from the miserable conditions and a high rate of death from spreading disease.[5]

An unnamed visitor to Mission Santa Clara wrote that the monjeríos were "so abominably infested with every kind of filth and nastiness, as to be rendered not less offensive than degrading of the human species."[7] Russian explorer Otto von Kotzebue wrote of his eyewitness account of the conditions at Mission Santa Clara:[5]

We were struck by the appearance of a large, quadrangular building, which, having no windows on the outside, and only one carefully secured door, resembled a prison for state criminals. It proved to be the residence appropriated by the monks, the severe guardians of chastity, to the young unmarried Indian women... These dungeons are opened two or three times a day, but only to allow prisoners to pass to and from church. I have occasionally seen the poor girls rushing out eagerly to breathe the fresh air, and driven immediately into the church like a flock of sheep, by an old ragged Spaniard armed with a stick. After mass, in the same manner they are hurried back to their prisons.[5]

Purpose

Conversion and sexual regulation

.jpg.webp)

By separating girls from their parents and communities, the monjeríos created physical spaces within the mission for easier indoctrination into Catholicism and for the missionaries, who were often Franciscan padres or men, to regulate girls' and women's sexuality.[1] This was to forcefully end Indigenous children's cultural connection to "indigenous forms of knowledge, authority, and power" and was a form of cultural genocide.[3]

There was a paternalistic approach taken toward Indigenous peoples by priests, who infantilized them in their violent attempts to convert, regulate their sexuality, and Hispanicize them.[5] Some Indigenous women, once deemed Hispanicized and Christianized, were then recruited to further the teachings and behavioral practices onto neophytes, and Spanish or Mexican women if available.[8] Women were often restricted from key access to the monjerío without permission from the padres.[8]

Social control and punishment

Girls and women were only allowed out of the quarters during the day at controlled times, often corresponding with church services and other mission practices. Even while being let out, the girls and women were monitored or chaperoned, and were locked into the quarters each night by the padres.[1][7] This forced housing in crowded quarters contributed to the quicker spread of deadly diseases.[1][5]

If girls or women disobeyed the orders of the padres or were found to be transgressing orders, they were punished with harsh measures. Punishment was used as a threat to condition girls and women to obey the orders of the padres and maintain the function of the monjeríos.[1][7] Friar Estevan Tápias, who was the president of the mission system in California between 1803 and 1812, reported on punishment as follows:[1]

The stocks in the apartment of the girls and single women are older than the Fathers who report on the mission. As a rule, the transgressions of the women are punished with one, two, or three days in the stocks, according to the gravity of the offense; but if they are obstinate in their evil intercourse, or run away, they are chastised by the hand of another woman in the apartment of the women. Sometimes, though exceedingly seldom, the shackles are put on.[1]

Spousal selection and child-rearing

Part of the function of the monjeríos was also to select a spouse for the child that would be to the benefit of the missionaries' ideology. Spousal selection was limited to Indigenous converts. From the padres view, this was to prevent or limit racial mixing, prevent the girls and women from undesired sexual encounters, as well as to maintain and continue to produce an exploitable workforce of Indigenous children and labor for the mission.[1][4]

Indigenous experiences

Family separation

Family separation was an inherent part of the monjeríos. Many girls and women endured family separation and disconnection as a result of the monjerío system. This often meant being taken from one's parents at a very young age, often around the age of seven.[3] This created an intergenerational gap in the transference of Indigenous knowledge and practices.[3] If never selected for marriage by the padres, the women could be kept at the mission facility for much of their adulthood.[6]

Victoria Reid was born in the Tongva village of Comicranga between the years of 1808 and 1810[4] as the daughter of the chief of the village.[9] At the age of six, she was taken from her parents to Mission San Gabriel for conversion and to live in a monjerío.[2] She was watched by Franciscan padres until the age of thirteen, when the padres selected a 41-year-old Indigenous man to be her husband. She had her first child at the age of fifteen.[4] She was eventually deemed Hispanicized and Christianized and was given two small plots of land known as parajes.[4]

Molestation

Indigenous peoples recalled experiences of molestation occurring between priests and girls and women at the monjeríos.[5] Translated in the late 1800s, American anthropologists and historians recorded the story of Fernando Librado, a Chumash man, who heard of how molestation occurred at Mission San Buenaventura at the site of the monjerío:[5]

The priest had an appointed hour to go there. When he got to the nunnery [monjerío], all were in bed in the big dormitory. The priest would pass by the bed of the superior [maestra] and tap on her shoulder, and she would commence singing. All of the girls would join in... When the singing was going on, the priest would have time to select the girl he wanted, carry out his desires... In this way the priest had sex with all of them, from the superior all the way down the line... The priest's will was law. Indians would lie right down if the priest said so.[5]

Resistance

Although monjeríos were dictated, monitored, and enforced to be strictly gendered spaces, Indigenous people's learned to navigate these expectations even under threat of harsh punishment.[5] In a recollection by Fernando Librado, he notes how some acts of resistance between Indigenous women and men were carried out to resist sexual confinement:[5]

The young women would take their silk shawls and tie them together with a stone on one end and throw them over the wall. This was done so that the Indian boys outside the high adobe wall could climb up. The boys would have bones from the slaughter house which were nicely cleaned and they would tie them on the shawls so that they could climb these shawls using the bones for their toes. The girls slept merely on [woven tule] mats, and there were no partitions or mats hung inside the room for privacy. The boys would stay in there with those girls till the early hours of the morning. Then, they would leave. They had a fine time sleeping with the girls.[5]

Escape

At the time of Cupeño trail of tears (the removal of the Cupeños from Agua Caliente to Pala) circa 1903, two very old women known as Bearfoot and Ysabel refused to return to San Antonio de Pala asistencia. According to a history of the removal, Bearfoot had fled into the mountains when she was young and planned to do so again if she was taken back to the mission.[10]

Ysabel, who evidently shared some of the same experiences as Bearfoot, confirmed, 'It is the memory of that [place] which drove Bearfoot into the chaparral...what we suffered there, how many years ago I cannot say, fifty, sixty, maybe more...See these scars! We had to keep fresh our memories of Pala Mission. Does the white man think it strange that we do not want to come? [We] and others, when young girls, had been held prisoners at Pala.'[10]

Rebellion

The miserable conditions at monjeríos and throughout the missions often led to rebellions.[11] In a rebellion at Mission Santa Cruz in 1812, a group of Indigenous people managed to gain control of mission operations after killing the head priest Andrés Quintana, which involved crushing and removing his testicles.[5] Ohlone Lorenzo Asisara reported that his father, who participated in the rebellion, and the others, unlocked the monjeríos as soon as the priest was dead, and then: "The single men left and without a sound gathered in the orchard at the same place where the Father was assassinated... After a short time the young unmarried women arrived in order to spend the night there. The young people of both sexes got together and had their pleasure."[5]

Memorialization

The scale and intensity of the punishment that occurred within monjeríos is not often covered in modern-day tourism or exhibitions of the missions, including at the modern-day renovated Spanish missions in California.[1] Some have argued that the tendency for historical narratives to obscure Indigenous women has further erased the memory of monjeríos.[12]

In some cases, the room may not be acknowledged at all in official exhibitions.[1] This lack of attention to the monjeríos differs from how they were valued in the mission period: "the importance of the monjeríos as indicated by this work [a survey of mission records] contrasts sharply with their lack of representation within current mission interpretation."[1]

Some historical narratives that are presented at official mission exhibitions tend to position the missions as symbols of progress and civilizational advancement, while Indigenous peoples are framed as primitive and usually disappear in the background of the story.[12] This has generally resulted in the erasure of Indigenous experiences at the missions, including at the monjeríos, sometimes with the implication that they were largely willing participants.[12]

References

- Vaughn, Chelsea K. (2011). "Locating Absence: The Forgotten Presence of Monjeríos in Alta California Missions". Southern California Quarterly. 93 (2): 141–174. doi:10.2307/41172570. ISSN 0038-3929. JSTOR 41172570.

- Bouvier, Virginia Marie (2001). Women and the conquest of California, 1542-1840 : codes of silence. Tucson. pp. 82–83. ISBN 0-8165-2025-9. OCLC 44713139.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Haas, Lisbeth (1996). Conquests and historical identities in California, 1769-1936 ([Pbk. ed., 1996] ed.). Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-520-91844-3. OCLC 45732484.

[taken] away from their parents from the age of seven or so until their marriage.

- Raquel Casas, Maria (2005). "Victoria Reid and the Politics of Identity". Latina legacies : identity, biography, and community. Vicki Ruíz, Virginia Sánchez Korrol. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 19–38. ISBN 978-0-19-803502-2. OCLC 61330208.

- Schmidt, Robert A.; Voss, Barbara L. (2005). Archaeologies of Sexuality. Routledge. pp. 43–47. ISBN 978-1-134-59385-9.

- "Private Women, Public Lives: Gender and the Missions of the Californias | Reviews in History". reviews.history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- Rizzo-Martinez, Martin (2022). "First Were Taken The Children, and Then the Parents Followed". We Are Not Animals : Indigenous Politics of Survival, Rebellion, and Reconstitution in Nineteenth-Century California (eBook). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-1-4962-3033-1. OCLC 1291169330.

- Bouvier, Virginia Marie (2001). Women and the conquest of California, 1542-1840 : codes of silence. Tucson. p. 84. ISBN 0-8165-2025-9. OCLC 44713139.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - A passage in time : the archaeology and history of the Santa Susana Pass State Historical Park, California. Richard Ciolek-Torrello. Tucson: Statistical Research. 2006. p. 65. ISBN 1-879442-89-2. OCLC 70910964.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Karr, Steven M. (September 2009). "The Warner's ranch Indian removal: cultural adaptation, accommodation, and continuity". California History. 86 (4): 24–84. doi:10.2307/40495232. JSTOR 40495232. Retrieved 2023-04-06 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- "Lorenzo Asisara (b. 1819)". Annenberg Learner. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- Kryder-Reid, Elizabeth (2016). "Performing Indigeneity". California mission landscapes : race, memory, and the politics of heritage (eBook). Minneapolis. ISBN 978-1-4529-5206-2. OCLC 957656495.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)