Mohammed Helmy

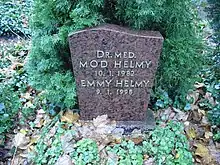

Mohammed Helmy (Arabic: محمد حلمي; 25 July 1901 – 10 January 1982) was an Egyptian physician who was recognized by Israel as one of the Righteous Among the Nations in 2013, with his name being listed at Yad Vashem in the city of Jerusalem.[1][2] Born in Sudan, he had moved to Berlin in the 1920s to study medicine and was later involved in saving many Jews from being exterminated by Nazi Germany during the Holocaust. After World War II, his family continued to live in Berlin, where he died in 1982. Helmy was the first Arab to be honoured (posthumously) as a Righteous Among the Nations; his nephews were summoned by Yad Vashem to receive the honour on his behalf, but were reluctant to do so because of the Arab–Israeli conflict, though they eventually attended the ceremony at the German foreign ministry instead of the local Israeli embassy.

Mohammed Helmy | |

|---|---|

| Born | 25 July 1901 Khartoum, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (now Sudan) |

| Died | 10 January 1982 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | Egyptian |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Employer | Robert Koch Institute |

| Known for | Saving Jews from the Holocaust during World War II alongside Frieda Szturmann |

| Spouse | Annie Ernst (c. 1943) |

| Awards | |

| Righteous Among the Nations |

|---|

|

| By country |

Biography

Early life and education

Mohammed Helmy was born in Khartoum, Sudan, to an Egyptian army major. He went to Berlin in 1922 to study medicine. He would go on to work as head of the urology department at the Robert Koch Hospital (later called Krankenhaus Moabit) after graduating and having been apprenticed by a Jewish professor of medicine, Prof. Georg Klemperer.

Nazi takeover of Germany

Extensively involved in Nazi policies, the hospital issued a wave of dismissals three months after the Nazis came to power in 1933, and would lose almost all its mid-level scientists.[3] Helmy himself was not fired at the time but was discriminated against, and eventually relieved of his duties in 1938 on the grounds that he was a non-Aryan Hamite, according to Nazi racial theory. He was also banned from working in hospitals, and from marrying his German fiancée, Annie Ernst.

In September 1939, a law requiring citizens of "enemy states" to register with authorities was implemented. Shortly after, Arabs in Germany and territories annexed or occupied by the Nazis were arrested, jailed, and deported to the Wülzburg internment camp near Nuremberg. Egyptian detainees in the camp were to be exchanged for Germans detained in Egypt. On October 3, 1939, Helmy was arrested and detained for a month before being sent to Wülzburg, where he fell seriously ill. He was released alongside the rest of the Egyptian prisoners in December. In January 1940, Heinrich Himmler ordered the internment of all adult male Egyptian nationals, which led to an ill Helmy being arrested for a second time. The Egyptian embassy managed to secure Helmy's early release in 1940 due to his deteriorating condition, sparing him another year in the internment camp.[4]

For over a year, Helmy was obliged to report to the police twice every day and provide proof every month that he was too ill to be present to the internment camp. Conscripted to the practice of Dr. Johannes Wedekind in Charlottenburg, Helmy fabricated sick notes for foreign workers to help them return to their countries, and also for German citizens to help them avoid labor civil conscription, and obligatory military service.[5]

In 1943, Helmy was summoned to the Prinz-Albrecht-Palais, the notorious Berlin headquarters of the SS. He was tasked with providing Muslim guests, including the Palestinian leader Amin al-Husseini, with medical care.[6]

When the Nazis began deporting Jews from Berlin, Helmy hid a friend, Anna Boros-Gutman, in a cabin he owned in the neighborhood of Buch for the entirety of the war. He managed to evade Gestapo interrogations, despite the authorities being well aware Helmy treated Jews. He also hid a number of Gutman's relatives from Nazi persecution with the help of Frieda Szturmann, also providing for them and attending to their medical needs.[1][5]

Four of Boros-Gutman's relatives were able to evade deportation thanks to Helmy and Szturmann. They would go on to emigrate to the United States.

Helmy was eventually able to marry Annie Ernst, and lived the rest of his life in Berlin, where he died in 1982. Szturmann died two decades earlier in 1962.[4]

Tributes

Discovery of Helmy's correspondence

When letters sent by Anna Boros and her relatives shortly after the war on behalf of Helmy and Szturmann to the Berlin Senate were discovered in the Berlin archives, they were submitted to Yad Vashem's Righteous Among the Nations Department. On 18 March 2013, the Commission for the Designation of the Righteous decided to award Helmy and Szturmann the title of Righteous Among the Nations. Helmy was the first Arab to receive the honor.[1][7]

Ceremony by Yad Vashem

Nephews of Helmy were sought by Yad Vashem to present them with the honour awarded to Helmy; they were, however, hesitant to accept the award, citing hostile relations between Israel and Egypt.[8] "We would be delighted if another country honoured him", they told German author Ronen Steinke who visited them.[9] Eventually, four years after he was recognized as the first Arab Righteous Among the Nations, a relative named Prof. Nasser Kotby agreed to receive the certificate from the Israeli ambassador to Berlin, but at a ceremony in the German Foreign Ministry,[10] not in the Israeli Embassy, due to the family's difficulty in receiving the honor directly from an Israeli institution.[11][12]

In Israeli films and other media

The Israeli filmmaker Taliya Finkel was researching Helmy's story since 2014. In 2017, her film Mohamed and Anna – In Plain Sight was released in the Israeli TV channel Kan 11. Finkel had located and made contact with Helmy's nephew Dr. Nasser Kotby, who agreed to participate in a new film and to be the first Arab to ever talk about the holocaust in a film. Finkel offered Dr Kotby to accept the Yad Vashem award in Berlin and Kotby agreed. He is the first Arab to receive the Righteous Among the Nations award in a ceremony that took place in October 27, 2018.

On 25 July 2023, Helmy's 122nd birthday was celebrated through a Google Doodle.[13]

Literature

- Ronen Steinke: Anna and Dr Helmy: How an Arab doctor saved a Jewish girl in Hitler's Berlin, Oxford University Press 2021[14]

References

- "Rescued by an Egyptian in Berlin". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Yad Vashem names Egyptian first Arab Righteous Among the Nations". Haaretz. 30 September 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- "RKI – The Robert Koch Institute under National Socialism". www.rki.de. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- "Mohamed Helmy". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- Steinke, Ronen (25 November 2021). Anna and Dr Helmy : how an Arab doctor saved a Jewish girl in Hitler's Berlin. ISBN 978-0-19-289336-9. OCLC 1259547044.

- Philpot, Robert (3 January 2022). "How an Egyptian doctor saved a Jewish teen in Nazi Berlin". Times of Israel. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- Rudoren, Jodi (1 October 2013). "Israel: Egyptian Rescuer Is Honored". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- "Family of WW2 Arab hero reject Israeli honor". i24 News. 20 October 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- Steinke, Ronen (2021). Anna and Dr. Helmy: How an Arab Doctor Saved a Jewish Girl in Hitler's Berlin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-19-289336-9.

- "Israel honours first recognised Arab Holocaust saviour". BBC News Online. BBC. 27 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- משפחתו של חסיד אומות העולם הערבי הראשון הסכימה לקבל תעודה מיד ושם, Haaretz, October 22, 2017

- "Egyptian doctor honoured for saving Jewish lives during the Holocaust". The Jewish Chronicle. 27 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- "Dr. Mod Helmy's 122nd Birthday". www.google.com. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- Adams, Tim. "Anna & Dr Helmy by Ronen Steinke review – The Schindler of the Surgery Room". www.guardian.com. Retrieved 30 December 2021.