Mistral-class amphibious assault ship

The Mistral class is a class of five amphibious assault ships built by France. Also known as helicopter carriers, and referred to as "projection and command ships" (French: bâtiments de projection et de commandement or BPC), a Mistral-class ship is capable of transporting and deploying 16 NH90 or Tiger helicopters, four landing craft, up to 70 vehicles including 13 Leclerc tanks, or a 40-strong Leclerc tank battalion,[4] and 450 soldiers. The ships are equipped with a 69-bed hospital, and are capable of serving as part of a NATO Response Force, or with United Nations or European Union peace-keeping forces.

BPC Dixmude in Jounieh Bay, Lebanon 2012. | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Mistral class |

| Builders | |

| Operators | |

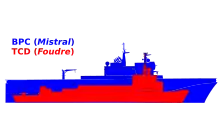

| Preceded by | Foudre class |

| Cost | €451.6 million (2012)[2] |

| In commission | December 2005 – present |

| Planned | 5 |

| Completed | 5 |

| Active | 5 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Amphibious assault ship |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 199 m (652 ft 11 in) |

| Beam | 32 m (105 ft 0 in) |

| Draught | 6.3 m (20 ft 8 in) |

| Installed power | 3 Wärtsilä diesel-alternators 16 V32 (6.2 MW) + 1 Wärtsilä Vaasa auxiliary diesel-alternator 18V200 (3 MW) |

| Propulsion | 2 Rolls-Royce Mermaid azimuth thrusters (2 × 7 MW), 2 five-bladed propellers |

| Speed | 18.8 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) |

| Range |

|

| Boats & landing craft carried |

|

| Capacity | 70 vehicles (including 13 Leclerc tank) or a 40-strong Leclerc tank battalion |

| Troops | 450 troops (or 250 troops plus a military staff of 200 men) |

| Complement | 20 officers, 80 petty officers, 60 quarter-masters |

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

| Armament |

|

| Aircraft carried | 16 heavy or 35 light helicopters |

| Aviation facilities | 6 helicopter landing spots |

Three ships of the class are in service in the French Navy: Mistral, Tonnerre, and Dixmude. A deal for two ships for the Russian Navy was announced by then French President Nicolas Sarkozy on 24 December 2010, and signed on 25 January 2011. On 3 September 2014, French President François Hollande announced the postponement of delivery of the first warship, Vladivostok, in response to the Russia–Ukraine crisis.[5][6] On 5 August 2015, President Hollande and Russian president Vladimir Putin announced that France would refund payments and keep the two ships; the two ships were later sold to Egypt.[7]

History

French doctrine of amphibious operations in 1997

In 1997, the DCNS started a study for a multi-purpose intervention ship (bâtiment d'intervention polyvalent or BIP). At the same time, the French doctrine of amphibious operations was evolving and being defined as the CNOA (French: Concept national des opérations amphibies, "National design for amphibious operations").[8] The BIP was to renew and increase the amphibious capabilities of the French Navy, which at the time consisted of two Foudre-class and two Ouragan-class landing platform docks.

The CNOA was to assert the French Navy's capability to perform amphibious assaults, withdrawals, demonstrations, and raids. This would allow the French Navy to further integrate into the doctrinal frameworks described by NATO's Allied Tactical Publication 8B (ATP8) and the European Amphibious Initiative. While the CNOA made air capabilities a priority, it also recommended an increase in the number of vehicles and personnel that could be transported and deployed;[9] the CNOA fixed the aim to project a force comprising four combat companies (1,400 men, 280 vehicles, and 30 helicopters) for ten days, in a 100-kilometre (62 mi)-deep sector; this force should be able to intervene either anywhere within 5,000 kilometres (3,100 mi) of Metropolitan France , or in support of French oversea territories or allies.[8] As well as joint operations with NATO and EU forces, any proposed ship had to be capable of inter-service operations with the Troupes de Marine brigades of the French Army.[10]

Evolution of the concept

The studies for a multi-purpose intervention ship (French: bâtiment d'intervention polyvalent, BIP) began during a time where the defence industries were preparing to undergo restructuring and integration. The BIP was intended to be a modular, scalable design that could be made available to the various European Union nations and constructed cooperatively, but political issues relating to employment and repartition of contracts caused the integration of the European nations with naval engineering expertise to fail, and saw the BIP project revert to a solely French concern.

In 1997, several common ship designs referred to as nouveau transport de chalands de débarquement (NTCD), loosely based on the aborted PH 75 nuclear helicopter carrier, were revealed. The largest design, BIP-19, was the future basis of the Mistral class. The BIP-19 included a 190-metre (620 ft) long flush deck, with a 26.5-metre (87 ft) beam, a draught of 6.5 metres (21 ft), and a displacement of 19,000 tonnes; dimensions which exceeded the requirements of the NTCD concept. Three smaller ship designs were also revealed, basically scaled-down BIP-19 versions, with a common beam of 23 metres (75 ft): BIP-13 (13,000 tonnes, 151 metres (495 ft)), BIP-10 (10,000 tonnes, 125 metres (410 ft)), and BIP-8 (8,000 tonnes, 102 metres (335 ft)). BIP-8 incorporated features of the Italian San Giorgio-class amphibious transports, but with a helicopter hangar.

At the design stage, the NTCD concept featured an aircraft lift on the port side (like the U.S. Tarawa class), another on the starboard side, one in the centre of the flight deck, and one forward of the island superstructure. These were later reduced in number and relocated: a main lift towards the aft of the ship was originally located to starboard but then moved to centre, and an auxiliary lift behind the island superstructure.[11] Concept drawings and descriptions created by Direction des Constructions Navales (DCN), one of the two shipbuilders involved, showed several aircraft carrier-like features, including a ski-jump ramp for STOBAR aircraft (like the AV-8B Harrier II and F-35B fighters), four or five helicopter landing spots (including one strengthened to accommodate V-22 Osprey or CH-53E Super Stallion helicopters), and a well deck capable of accommodating a Sabre-class landing craft, or two LCAC hovercraft.[12] A French Senate review concluded that STOBAR aircraft were outside the CNOA's scope, requiring design changes.[13]

The NTCD was renamed Porte-hélicoptères d'intervention (PHI, for "intervention helicopter carrier") in December 2001, before being eventually named Bâtiment de projection et de commandement (BPC) to emphasize the amphibious and command aspects of the concept.[14]

Design and construction

At Euronaval 1998, France confirmed plans to build vessels based on the BIP-19 concept. Approval for construction of two ships, Mistral and Tonnerre, was received on 8 December 2000. A construction contract was published on 22 December and, after getting the public purchase authority's approval (Union des groupements d'achats publics, UGAP) on 13 July 2001, was awarded to DCN and Chantiers de l'Atlantique in late July. An engineering design team was established at Saint-Nazaire in September 2001 and, following consultation between DCA and the Délégation Générale pour l'Armement (General Delegation for Ordnance, DGA), began to adapt the BIP-19 design. In parallel, the concept was refined by DGA, DCN, the Chief of the Defence Staff and Chantiers de l'Atlantique. During the design validation process, a 1⁄120th scale model was built and tested in a wind tunnel, revealing that in strong crosswinds, the ship's height and elongated superstructures created turbulence along the flight deck. The design was altered to minimise the effects and provide better conditions for helicopter operations.[15]

The ships were constructed at various locations in two major and several minor components and united on completion. DCN, the head of construction and responsible for 60% of the value of construction and 55% of the work time, assembled the engines in Lorient, combat systems in Toulon, and the rear half of the ship, including the island superstructure, in Brest. STX Europe, a subsidiary of STX Shipbuilding of South Korea, constructed the forward halves of each ship in Saint-Nazaire, and was responsible for transporting them to DCN's Brest shipyard for final assembly.[1] Other companies were involved in the construction: some work was outsourced to Gdańska Stocznia "Remontowa", while Thales supplied radars and communications systems. Each ship was predicted to take 34 months to complete, with design and construction for both costing 685 million Euros (approximately the same cost for a single ship based on HMS Ocean or USS San Antonio, and approximately the same cost as the preceding Foudre-class amphibious ships, which displaced half the tonnage of the Mistral class and took 46.5 months to complete).[16]

Starting from Dixmude, the rest of the French Mistrals and the two Russian Mistrals were built in Saint-Nazaire by STX France, which is jointly owned by STX Europe, Alstom and the French government, with STX Europe having a majority stake. DCNS will provide the combat system.[1] The Russian ships' sterns were built in Saint Petersburg, Russia, by Baltic Shipyard.

DCN laid the keels for the aft part of both ships in 2002; Mistral on 9 July, and Tonnerre on 13 December.[17] Chantiers de l'Atlantique laid the keel of the forward part of Mistral on 28 January 2003, and of Tonnerre later. The first block of the rear of Tonnerre was put in a dry dock on 26 August 2003, and that of Mistral on 23 October 2003. The two aft sections were assembled side by side in the same dry dock. The forward section of Mistral left Saint-Nazaire under tow on 16 July 2004 and arrived in Brest on 19 July 2004. On 30 July, the combination of the two halves through a process similar to jumboisation began in dock no. 9. Tonnerre's forward section arrived in Brest on 2 May 2005 and underwent the same procedure.

Mistral was launched on schedule on 6 October 2004, while Tonnerre was launched on 26 July 2005.[18] Delivery was scheduled for late 2005 and early 2006 respectively, but was postponed for over a year due to issues with the SENIT 9 sensor system and deterioration to the linoleum deck covering of the forward sections. They were commissioned into the French Navy on 15 December 2006 and 1 August 2007, respectively.[18]

The 2008 French White Paper on Defence and National Security forecast that two more BPCs would be in French Navy service by 2020.[19] In 2009, a third ship was ordered earlier than expected as part of the French government's response to the recession which began in 2008.[20] Construction began on 18 April 2009 in Saint-Nazaire; the entire ship was built there due to cost constraints.[21] On 17 December 2009, it was announced that this third ship would be named Dixmude.[22][23] It had been suggested to use the historic name of Jeanne d'Arc following the decommissioning of the helicopter cruiser of that name in 2010, but it was opposed by some French naval circles because France no longer operated a dedicated training ship (the traditional role of warships named Jeanne d'Arc) and now rotated the training role between multiple ships in the fleet.[24] The possibility of a fourth Mistral-class ship was officially abandoned in the 2013 French White Paper on Defence and National Security.

Features and capabilities

Based on displacement tonnage, Mistral and Tonnerre are the largest ships in the French Navy after the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle, for roughly the same height above water.

Aviation

The flight deck of each ship is approximately 6,400 square metres (69,000 sq ft). The deck has six helicopter landing spots, one of which is capable of supporting a 33-tonne helicopter. The 1,800-square-metre (19,000 sq ft) hangar deck can hold 16 helicopters, and includes a maintenance area with an overhead crane. To aid launch and recovery, a DRBN-38A Decca Bridgemaster E250 landing radar and an optical landing system are used.

The flight and hangar decks are connected by two aircraft lifts, each capable of lifting 13 tonnes. The 225-square-metre (2,420 sq ft) main lift is located near the stern of the ship, on the centreline, and is large enough for helicopters to be moved with their rotors in flight configuration. The 120 square metres (1,300 sq ft) auxiliary lift is located aft of the island superstructure.

Every helicopter operated by the French military is capable of flying from these ships. On 8 February 2005, a Westland Lynx of the Navy and a Cougar landed on Mistral. The first landing of a NH90 took place on 9 March 2006. Half of the air group of the BPCs is to be constituted of NH-90s, the other half being composed of Tigre attack helicopters. On 19 April 2007, Puma, Écureuil and Panther helicopters landed on Tonnerre. On 10 May 2007, a MH-53E Sea Dragon of the US Navy landed on her reinforced helicopter spot off the U.S. Naval Station Norfolk.

According to Mistral's first commanding officer, Capitaine de vaisseau Gilles Humeau, the size of the flight and hangar decks would allow the operation of up to thirty helicopters.[25] Mistral aviation capabilities approach those of the Wasp-class amphibious assault ships, for roughly 40% the cost and crew requirements of the American ship.[26]

Amphibious transport

Mistral-class ships can accommodate up to 450 soldiers, although this can be doubled for short-term deployments. The 2,650-square-metre (28,500 sq ft) vehicle hangar can carry a 40-strong Leclerc tank battalion, or a 13-strong Leclerc tank company and 46 other vehicles. By comparison, Foudre-class ships can carry up to 100 vehicles, including 22 AMX-30 tanks, in the significantly smaller 1,000-square-metre (11,000 sq ft) deck.

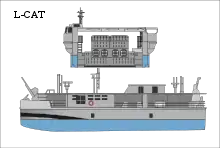

The 885-square-metre (9,530 sq ft) well deck can accommodate four landing craft. The ships are capable of operating two LCAC hovercraft, and although the French Navy appears to have no intention of purchasing any LCACs,[27] this capability improves the class' ability to interoperate with the United States Marine Corps and the British Royal Navy. Instead the DGA ordered eight French-designed 59-tonne EDA-R (Engin de débarquement amphibie rapide) catamarans for operation from the Mistral class.[28] The EDA-S Amphibious Standard Landing Craft (Engins de Débarquement Amphibie – Standards) were subsequently ordered to replace CTM landing craft. These landing craft began delivery in 2021. Eight are envisaged for operation from the Mistral class and they have a payload capacity of 65 to 80 tonnes and a maximum speed of 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph) at full load.[29][30][31]

Two landing craft in the well deck of Mistral

Two landing craft in the well deck of Mistral Aft of Tonnerre, with the well deck door and elevator

Aft of Tonnerre, with the well deck door and elevator

Command and communications

Mistral-class ships can be used as command and control ships, with a 850-square-metre (9,100 sq ft) command centre which can host up to 150 personnel. Information from the ship's sensors is centralised in the SENIT system (Système d'Exploitation Navale des Informations Tactiques, "System for Naval Usage of Tactical Information"),[32] a derivative of the US Navy's Naval Tactical Data System (NTDS). Problems in the development of the SENIT 9 revision contributed to the one-year delay in the delivery of the two ships. SENIT 9 is based around Thales' tri-dimensional MRR3D-NG Multi Role Radar, which operates on the C band and incorporates IFF capabilities. SENIT 9 can also be connected to NATO data exchange formats through Link 11, Link 16 and Link 22.

For communications, the Mistral-class ships use the SYRACUSE satellite system, based on French satellites SYRACUSE 3-A and SYRACUSE 3-B which provide 45% of the Super High Frequency secured communications of NATO. From 18 to 24 June 2007, a secure video conference was held twice a day between Tonnerre, then sailing from Brazil to South Africa, and VIP visitors at the Paris Air Show.[33]

Armament

As built, the two Mistral-class ships were armed with two Simbad launchers for Mistral missiles and four 12.7 mm M2-HB Browning machine guns.[18] Two Breda-Mauser 30 mm/70 guns are also included in the design, though not installed as of 2009. Following the experiences of French naval commanders during Opération Baliste, the French deployment to aid European citizens in Lebanon during the 2006 war, proposals to improve the self-defence capabilities of the two Mistral-class ships were supported by one of France's chiefs of staff.[18][34] One suggestion is to upgrade the dual-launching, manual Simbad launchers to quadruple-launching, automatic Tetral launchers.[35]

Incidents such as the near-loss of the Israeli corvette INS Hanit to a Hezbollah-fired anti-ship missile during the 2006 Lebanon War have shown the vulnerability of modern warships to asymmetric threats, with the Mistral-class ships considered under-equipped for self-defence in such a situation.[25] Consequently, Mistral and Tonnerre cannot be deployed into hostile waters without sufficient escorting ships. This problem is compounded by the small number of escort ships in the French Navy; there is a five-year gap between the decommissioning of the Suffren-class frigates and the commissioning of their replacements, the Horizon-class and FREMM frigates.

In late 2011, the French Navy selected the NARWHAL20 remote weapon station (RWS) to equip Mistral ships for close-in self-defense. Nexter Systems will deliver two NARWHAL20B guns for each ship, chambered in 20×139mm ammunition, with one gun covering the port bow and the other covering the starboard stern. Dixmude was the first of the vessels outfitted with the cannons in March 2016.[36]

In late 2013, the French Navy equipped all three Mistrals with two M134 Miniguns each; intended for close-in self-defence against asymmetric threats faced during anti-piracy operations, such as speedboats and suicide boats.[37]

In December 2014, the French Navy awarded a contract to Airbus to study the integration of the Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) on Mistrals. This is to increase the ships' naval fire support capabilities, as 76 mm and 100 mm guns have been determined to have insufficient range and lethality. The MLRS is in French Army service, using a GPS-guided rocket with a range of 70 km (43 mi) and a unitary 90 kg (200 lb) high-explosive warhead.[38]

One of the two SIMBAD launchers of Mistral

One of the two SIMBAD launchers of Mistral An uncovered SIMBAD launcher

An uncovered SIMBAD launcher Machine gun on Mistral

Machine gun on Mistral

Hospital

Each ship carries a NATO Role 3 medical facility,[39][40] i.e., equivalent to the field hospital of an Army division or army corps, or to the hospital of a 25,000-inhabitant city, complete with dentistry, diagnostics, specialist surgical and medical capabilities, food hygiene and psychological capabilities.[41] A Syracuse-based telemedicine system allows complex specialised surgery to be performed.[42]

The 900 m2 (9,700 sq ft) hospital[43] provides 20 rooms and 69 hospitalisation beds, of which 7 are fit for intensive care.[44] The two surgery blocks come complete with a radiology room[45] providing digital radiography and ultrasonography, and that can be fitted with a mobile CT scanner.[40] 50 medicalised beds are kept in reserve and can be installed in a helicopter hangar to extend the capacity of the hospital in case of emergency.[46]

Propulsion

The Mistral class are the first ships of the French Navy to use azimuth thrusters. The thrusters are powered by electricity from five 16-cylinder Wärtsilä 16V32 diesel alternators, and can be oriented in any angle. This propulsion technology gives the ships significant manoeuvering capabilities, as well as freeing up space normally reserved for propeller shafts.

The long-term reliability of azimuth thrusters in military use is yet to be rigorously studied, but the technology has been employed aboard ships in several navies, including the Dutch Rotterdam class, the Spanish Galicia class, and the Canadian Kingston class.

Accommodation

The space gained by the use of the azimuth thrusters allowed for the construction of accommodation areas where no pipes or machinery are visible. Located in the forward section of the ship, crew cabins aboard Mistral-class ships are comparable in comfort levels to passenger cabins aboard contemporary cruise ships.[39] Each of the fifteen officers have an individual cabin. Senior non-commissioned officers share two-man cabins, while junior crew and embarked troops use four- or six-person cabins. Conditions in these accommodation areas are said to be better than in most barracks of the French Foreign Legion, and when United States Navy vice-admiral Mark Fitzgerald inspected one of the Mistral-class ships in May 2007, it was claimed that he would have used the same accommodation area to host a crew three times the size of Mistral's complement.[39]

Operational history

The BPCs are certified as members of the naval component of the NATO Response Force, which allows them to take part in a Combined Joint Task Force. France provided forces to NRF-8 in January 2007, including a Commander Amphibious Task Force and eight ships. The next contribution took place in January 2008 in NRF-10, after exercises Noble Midas which tested link 16 and the SECSAT system which operationally controls submarines. The forces can be set up on 5 to 30 days' notice.

Mistral made her maiden voyage from 21 March to 31 May 2006, cruising in the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean.

Following the start of the 2006 Lebanon War, Mistral was one of four French ships deployed to the waters off Lebanon as part of Opération Baliste. These ships were to protect, and if necessary evacuate, French citizens in Lebanon and Israel. Mistral embarked 650 soldiers and 85 vehicles, including 5 AMX-10 RC and about 20 VABs and VBLs. Four helicopters were also loaded aboard, with another two joining the ship near Crete. During her deployment, Mistral evacuated 1,375 refugees.[47]

Tonnerre's maiden voyage occurred between 10 April and 24 July 2007. During this voyage, Tonnerre was involved in Opération Licorne, the French co-deploying complement to the United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire following the Ivorian Civil War. Gazelle and Cougar helicopters of the French Air Force operated from the ship during 9 July.

At the start of 2008, Tonnerre was involved in the Corymbe 92 mission (see Standing French Navy Deployments), a humanitarian mission in the Gulf of Guinea. During this deployment, Tonnerre acted on tip-offs from the European Maritime Analysis Operation Centre – Narcotics, and intercepted 5.7 t (5.6 long tons; 6.3 short tons) of smuggled cocaine: 2.5 t (2.5 long tons; 2.8 short tons) from a fishing vessel 520 kilometres (280 nmi) from Monrovia on 29 January, and 3.2 t (3.1 long tons; 3.5 short tons) from a cargo ship 300 kilometres (160 nmi) off Conakry.

In May 2008, Cyclone Nargis struck Burma; the worst natural disaster to hit the region. Mistral, which was operating in the East Asia area at the time, loaded humanitarian aid supplies, and sailed to Burma. The ship was refused entry to the nation's ports;[48][49] the 1,000 tons of humanitarian supplies had to be unloaded in Thailand and handed over to the World Food Program.

French Foreign Minister Alain Juppé announced on 23 May 2011 that Tonnerre would be deployed with attack helicopters to the Libyan coast to enforce UN resolution 1973.[50]

In September/October 2021, Tonnerre and Mistral deployed together for a major military exercise incorporating two helicopter groups (with 25 helicopters), an amphibious engagement group and two escort vessels (the frigates Forbin and Provence). The exercise was designed to permit units of the navy and army to train "in a high intensity setting" for joint operations.[51]

Export

Since 1997, and particularly since the Euronaval 2007, the Mistral type has been promoted for export. The "BPC family" comprises the BPC 140 (13,500 tonnes), the BPC 160 (16,700 tonnes) and the BPC 250 (24,542 tonnes, 214.5 metres (704 ft) long). The BPC 250 was the design from which the final Mistral-class design was derived: the reduction in length and other modifications were a price-saving exercise.[52] The BPC 250 concept was one of two designs selected for the Canberra-class amphibious warfare ships, to be constructed for the Royal Australian Navy.[52] The design finally chosen was the Spanish Buque de Proyección Estratégica-class amphibious ship.[52]

In 2012, the Royal Canadian Navy showed "strong interest" in buying two Mistral ships. The two Canadian ships were to be built by SNC Lavalin, with an option to buy a third. The project represented a total investment of $2.6 billion.[53][54] Canada had also pursued the two former Russian vessels, and Canada's defence minister held a face to face exchange at the NATO Ministerial in June 2015.[55] Canada's attempt to purchase Mistral ship was dropped due to budgetary constraints. As of late 2011, the Polish Navy has been working closely with the Polish Ministry of Defense to purchase one Mistral ship. The Indian Navy has also expressed interest in the design of the Mistral type as a Multi-Role Support Vessel. Brazil and Turkey could in time consider purchasing BPCs, but in the end Turkey also chose a derivative of Navantia's Juan Carlos I, TCG Anadolu.[56] Algeria is also considering the purchase of two BPCs.[57][58] South Africa, the United Arab Emirates, Malaysia and Singapore also reportedly expressed interest in the Mistral class.[59]

Russian purchase

In August 2009, General Nikolai Makarov, Chief of the Russian General Staff, suggested Russia planned to purchase one ship and intended to later construct three further ships in Russia. In February 2010, he said that construction would start sometime after 2015 and would be a joint effort with France.[60] French President Nicolas Sarkozy favoured the building of the first two ships in France and only the second two in Russia. According to Moscow-based Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies, the first ship would be entirely built and assembled in France from 2013, the second would also be built in France, delivered in 2015, but with a higher proportion of Russian components. Two more would be built in Russia by a DCNS/Russian United Shipbuilding Corporation (USC) joint-venture.[61] On 1 November 2010, Russia's USC and France's DCNS and STX France signed an agreement to form a consortium, including technology transfer, the USC president stated that it was linked to the Mistral deal.

On 24 December 2010, after eight months of talks, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev approved the purchase by Rosoboronexport of two Mistral-class ships (and an option for two more) from France for €1.37 billion (€720 million for the 1st ship; €650 million for the second).[62] The first ship was expected to be delivered in late 2014 or early 2015; Russia made an advance payment in early 2011 pursuant to 25 January 2011 memorandum of understanding between the two parties. On 25 January 2011, the final agreement between Russia and France was signed.

In the United States, six Republican senators, including John McCain, complained to the French ambassador in Washington about the proposed sale;[63] Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, the top Republican on the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, introduced a resolution that "France and other member states of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union should decline to sell major weapons systems or offensive military equipment to the Russian Federation."[64] On 8 February 2010, Defense Secretary Robert Gates told French officials that the US was "concerned"; however, accompanying US officials said there is little the US could do to block the deal,[65] and that it "did not pose a major problem."[66] The same day, the deal was granted by France's DGA. It was the first major arms deal between Russia and a NATO country since the Soviet Union's acquisition of Rolls-Royce Nene and Rolls-Royce Derwent turbojet engines in 1947.[67] NATO members Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia protested the deal; Lithuania's Defence Minister Rasa Jukneviciene stated that "[i]t's a mistake. This is a precedent, when a NATO and EU member sells offensive weaponry to a country whose democracy is not at a level that would make us feel calm."[68]

Some design changes were needed, such as for compatibility with Russian Ka-52 and Ka-27 helicopters. In 2013, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin stated that the ships would not be able to operate in Russia's climate,[69] and required a grade of diesel fuel not produced in Russia.[70] Russian General Staff General Nikolai Makarov announced that the first ship would be deployed to the Russian Pacific Fleet, and could transport troops to the Kuril Islands if sought.[71] According to Nikolai Makarov, the chief reason for the Mistral purchase over domestic producers was that Russia required an unacceptable delay of ten years to develop the technologies needed. In March 2011, the deal stalled on Russian demands for sensitive NATO technologies to be included with the ships.[72] In April 2011, the Russian President Dmitry Medvedev fired the senior Navy official overseeing the talks with France. On 17 June 2011, the two nations signed an agreement for two ships for $1.7 billion.[73]

In September 2014, the Mistral sale was put on hold by French President Francois Hollande due to an arms embargo of Russia over the illegal Russian annexation of Crimea.[74] French foreign minister Laurent Fabius evaluated the deal in response to the Crimean referendum and the enactment of "phase two" economic sanctions; cancelling the Mistral contract was considered to be "phase three"; Fabius noted that cancelling would damage France's economy.[75] In May 2014, Paris had guaranteed the two ships' completion.[76] In November 2014, the Hollande government placed a hold on the first delivery to Russia and set two conditions: a ceasefire in Ukraine and a political agreement between Moscow and Kyiv.[77] In December 2014, Russia gave the French government a choice to deliver the two ships or refund the $1.53 billion purchase price.[78] On 26 May 2015, Russian news agencies quoted Oleg Bochkaryov, deputy head of the Military Industrial Commission, as saying "Russia won't take them, it's an accomplished fact. Now there's only one discussion—concerning the money sum that should be returned to Russia."[79] On 5 August 2015 it was announced that France shall return Russia's partial payments and keep the two ships intended for Russia.[80][81]

Egyptian purchase

On 7 August 2015, a French diplomatic source confirmed that President Hollande discussed the matter with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi during his visit to Egypt during the inauguration of the New Suez Canal in Ismailia.[82][83] Subsequently, Egypt and France concluded the deal to acquire the two former Russian Mistrals for roughly 950 million euros, including the costs of training Egyptian crews.[84][85] Speaking on RMC Radio, Jean-Yves Le Drian, French Defence Minister, said that Egypt had already paid the whole price for the helicopter carriers. Egypt also purchased the Russian helicopters that were planned for the ships.

Mistral 140

DCNS unveiled a model of a smaller version of the standard Mistral BPC 210 ship called the Mistral 140 in September 2014 at the Africa Aerospace and Defence 2014 exhibition in Pretoria, South Africa. Compared to the full-sized ship's 21,500 tons displacement and 199 m (653 ft) length with six helicopter landing spots, the 140 would have a displacement of 14,000 tons, 170 m (560 ft) long with five helicopter landing spots. It would be 30 m (98 ft) wide with a range of 6,000 nmi (6,900 mi; 11,000 km) at 15 knots.

Like the original plans for the Mistral BPC 210 that have not yet come to fruition, the Mistral 140 would have naval guns at the left stern and at the right side of the bow, with heavy machine gun posts on both sides. There would be a well dock in the stern for landing craft, and two alcoves on each side to launch rigid-hulled inflatable boats, along with a crane positioned amidships behind the superstructure. The hangar deck would have space for ten helicopters, with a 400 m2 joint operations centre for a command staff. There would be accommodation for about 500 troops as well as over 30 vehicles and a 30-bed hospital. Propulsion would be provided by two azimuth pods and a bow thruster, probably an all-electric propulsion system like the BPC 210.

DCNS is advertising the Mistral 140 as "a political tool for civilian and military action" for countries that cannot afford the standard Mistral vessels. Roles listed include humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, crisis management, force protection, joint headquarters command, medical and logistics support and transport of military forces. The company is pitching the ship to countries less likely to engage in combat operations which need something more like a multi-role support or logistics ship, particularly the South African Navy.[86]

Ships

| Pennant no. | Name | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Homeport |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French Navy | |||||

| L9013 | Mistral | 10 July 2003 | 6 October 2004 | February 2006 | Toulon |

| L9014 | Tonnerre | 26 August 2003 | 26 July 2005 | December 2006 | Toulon |

| L9015 | Dixmude | 18 April 2009 | 17 September 2010[87] | 27 December 2012[88] | Toulon |

| Egyptian Navy | |||||

| L1010 [89] | Gamal Abdel Nasser (ex-Vladivostok) | 18 June 2013[90] | 20 November 2014[91][92] | 2 June 2016[93] | Safaga[94] |

| L1020 | Anwar El Sadat (ex-Sevastopol) | 1 February 2012 | 15 October 2013[95][96] | 16 September 2016[97] | Alexandria |

See also

- Project 23900 amphibious assault ship – Russia's future landing helicopter dock, a replacement for the two undelivered Mistral-class vessels

- Dokdo-class amphibious assault ship

- Canberra-class landing helicopter dock

Notes and references

- "Mistral Construction Program". Globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "Projet de loi de finances pour 2013 : Défense : équipement des forces" (in French). Senate of France. 22 November 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2014. Dixmude cost France €451.6m at FY2012 prices

- "Nexter presenting NARWHAL®, its remotely operated 20mm gun turret, at the Euronaval 2016 trade show between 17 and 21 October". nexter-group.fr. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- "BPC Mistral". netmarine.net. Archived from the original on 2 January 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- de la Baume, Maïa; Gladstone, Rick (3 September 2014). "France Postpones Delivery of Warship to Russia". The New York Times Company.

- "Ukraine crisis: France halts warship delivery to Russia". BBC. 3 September 2014.

- "France Says Egypt To Buy Mistral Warships". Defense News. Agence France-Presse. 23 September 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Credat, Arnault (April 2005). Veyrat, Jean-Marie (ed.). "The national concept of amphibious operations" (PDF). Objectif Doctrine. Metz: Ministry of Defence (36). ISSN 1267-7787. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2008.

- "BPC Classe Mistral: Fer de Lance de la Projection de Forces" (PDF). Bulletin d'études de la Marine (in French). Ministère de la Défense (33): 7. March 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2006.

- Terre information magazine ISSN 0995-6999, no. 184 (May 2007)

- "Navy painter André Lambert". Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- TCD classe NTCD Archived 15 August 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- "Avis du Sénat français no 90 du 22 novembre 2001". Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Histoire du BPC Mistral (2000 - 2006)". Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Michaut, Cécile (1 June 2007). "Air streams on the water". Office national d'études et de recherches aérospatiales. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- Marines : Mistral Shows Up LPD 17 Archived 30 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, in Strategy Page (29 May 2007)

- "Découpe de la première tôle du Tonnerre" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Saunders, Stephen, ed. (2008). Jane's Fighting Ships 2008-2009. Jane's Fighting Ships (111th ed.). Coulsdon: Jane's Information Group. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-7106-2845-9. OCLC 225431774.

- Mallet, Jean-Claude (2008). The French White Paper on Defence and National Security (PDF). New York: Odile Jacob Publishing Corporation. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-9768908-2-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2009.

- Pierre, Tran (18 December 2008). "French Detail New Orders, Procurement Changes". DefenseNews.

- DCNS, Tran (17 April 2009). "France Orders Third Projection and Command Vessel". DefenseNews. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010.

- "Le 3ème BPC de la Marine nationale s'appellera Dixmude". Mer et Marine. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Après le Mistral et le Tonnerre, le «Dixmude», Ministry of Defence

- Merchet, Jean-Dominique (17 April 2009). "Le troisième BPC de la Marine sera-t-il la nouvelle "Jeanne d'Arc" ?". Libération. Archived from the original on 9 October 2009.

- Véronique Sartini, "Entretien avec le capitaine de vaisseau Gilles Humeau", in Défense & Sécurité Internationale (ISSN 1772-788X), no 19 (October 2006)

- "The Mistral Amphib is a Goldmine of Good Ideas". Defense News. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Essais d'enradiage de LCAC réussis pour le BPC Tonnerre". Mer et Marine. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Bruno Daffix (15 June 2009). "La DGA notifie l'acquisition d'engins de débarquement amphibie rapides". Ministry of Defence (France). Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- "French Navy receives two EDA-S Amphibious Standard Landing Crafts".

- "First Two EDA-S Next Gen Amphibious Landing Craft Delivered to French DGA". 25 November 2021.

- "French Navy EDA-S landing craft successfully conclude end-user evaluations".

- "Présentation du SENIT". Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Brève du ministère de la Défense français du 3 juillet 2007

- Magne, Xavier (September–October 2007). "L'opération Baliste". Défense & Sécurité Internationale (in French) (2). ISSN 1772-788X.

- "Améliorer l'autoprotection des BPC du type Mistral". Mer et Marine (in French). 29 June 2007. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012.

- "Nexter NARWAHL 20mm RWS Fitted on French Navy Mistral Class LHD Dixmude". Navyrecognition.com. 17 March 2016. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016.

- "Marine Nationale : 12 canons multitubes M134 Dillon ont été livrés. Les tourelles téléopérées arrivent". Le Marin (in French). Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017 – via Scoop.it.

- "French Navy Looking to Deploy Army MLRS from LHDs for Coastal Fire Support Missions". Navyrecognition.com. 21 January 2016. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016.

- Mackenzie, Christina. "Aboard the Mistral". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Sicard, B.; Perrichot, C.; Tymen, R. "Mistral: a new concept of medical platform" (PDF). NATO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Chapter 16: Medical Support". NATO Logistics Handbook. Archived from the original on 20 May 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- "Démonstration des moyens satellites du BPC Tonnerre au salon du Bourget". Mer et Marine (in French). 12 June 2007. Archived from the original on 13 February 2008.

- "Le Service de Recrutement de la Marine en Seminaire a bord du Mistal" (in French). French Ministry of Defence. 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- "Le Bâtiment de Projection et de Commandement Mistral" (in French). French Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- "Mistral (L9013) Bâtiment de projection et de commandement (BPC)" (PDF) (in French). French Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- "BPC : Bâtiments de Projection et de Commandement". Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Groizeleau, Vincent. "French Navy validates the BPC concept in Lebanon". Sea And Navy. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- "Tropical Cyclone Nargis : French humanitarian aid (May 29, 2008)". Minister of Foreign Affairs (France). 29 May 2008. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Myanmar: the Mistral unloads its freight in Thailand". Minister of Defence (France). 27 May 2008. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020.

- Norton-Taylor, Richard (23 May 2011). "Apache helicopters to be sent into Libya by Britain". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Vavasseur, Xavier (13 October 2021). "Two French LHDs And 25 Helicopters Take Part In Large Amphibious Exercise". navalnews.com. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- Borgu, Aldo (23 July 2004). "Capability of First Resort?: Australia's future amphibious requirement". Strategic Insights. Australian Strategic Policy Institute. 8. ISSN 1449-3993. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- Cabirol, Michel (31 May 2012). "DCNS propose la frégate Fremm et le Mistral au Canada". La Tribune (in French). Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Le Canada s'intéresse aux Mistral de DCNS". Reuters (in French). 7 December 2010. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015.

- Pugliese, David (20 September 2015). "Canada was actively pursuing possible purchase of Mistral-class ships – initiative on hold because of election". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 11 February 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- Henrotin, Joseph (July 2006). "Les outsiders de la puissance aéronavale : une prospective à 10 ans". Défense & Sécurité Internationale (in French) (17). ISSN 1772-788X.

- Guisnel, Jean (7 May 2008). "Premiers détails sur la vente de quatre FREMM à l'Algérie". Le Point. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012.

- "Escale du "Tonnerre" Bâtiment de projection et de commandement en Algérie, le 9 et 10 juin 2008" (Press release) (in French). Government of France. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- McHugh, Jess (26 August 2015). "France Russia Mistral Ships Update: Malaysia To Buy Aircraft Carrier?". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- "La construction en Russie de navires de type Mistral possible d'ici 5-10 ans (Etat-major)". RIA Novosti. 17 February 2010. Archived from the original on 21 February 2010.

- Arkhipov, Ilya (11 June 2010). "Russia $12 Billion Arms Spree May Benefit DCNS, Iveco". Bloomberg.

- "Russia to purchase four French warships". Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 21 September 2010. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013.

- Cody, Edward (2 February 2010). "Critics say proposed sale of French Mistral ship to Russia will harm region". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016.

- Ros-Lehtinen, Ileana (16 December 2009). "Expressing the sense of the House of Representatives that France and other member states of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union should decline to sell major weapons systems or offensive military equipment to the Russian Federation". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016.

- Shanker, Tom (8 February 2010). "Gates Voices Concern About Warship Sale to Russia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 May 2017.

- Tran, Pierre (8 February 2010). "France, U.S. Discuss Russian Mistral Carrier Query". defensenews.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012.

- Kramer, Andrew (12 March 2010). "As Its Arms Makers Falter, Russia Buys Abroad". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 May 2018.

- France, Agence. "Baltic states fault France's warship deal with Russia | Navy News at DefenseTalk". Defencetalk.com. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- Pike, John. "French Warship for Russia 'Won't Work in Cold' - Minister". Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Pike, John. "No Fuel in Russia For French-Built Warship - Deputy PM". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Французы придут морем [French will come by sea]. Vedomosti (in Russian). 27 December 2010. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010.

- Pike, John. "Mistral talks stumble over sensitive technology". Archived from the original on 7 September 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Pike, John. "Russia signs $1.7 bln deal for 2 French warships". Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Europe and Russia". The Economist. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017.

- "France May Scrap Russian Warship Deal over Ukraine Crisis". RIA Novosti. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original on 2 August 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Russia; France guarantees Mistral deal". Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Stothard, Michael; Thomson, Adam; Hille, Kathrin (26 November 2014). "France Suspends Mistral Warship Delivery to Russia". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2014.

- LaGrone, Sam (8 December 2014). "Russia to France: Give Us the Mistrals or a Refund". USNI News. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014.

- "Russia no longer wants French-made Mistral helicopter carriers". Financial Times. 26 May 2015.

- "Entretien téléphonique avec M. Vladimir Poutine - accords sur les BPC". elysee.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 9 August 2015.

- "Telephone conversation with President of France Francois Hollande". kremlin.ru. Archived from the original on 8 August 2015.

- Sallon, Hélène (7 August 2015). "Mistral : l'Arabie saoudite et l'Egypte " sont prêtes à tout pour acheter les deux navires "". Le Monde (in French). Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "Egypt, Saudi Arabia 'desperate' to purchase Mistral warships". france24. 7 August 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Dalton, Matthew (23 September 2015). "France to Sell Two Mistral Warships to Egypt". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Cullinane, Susannah; Martel, Noisette (23 September 2015). "France to sell Egypt two warships previously contracted to Russia". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Fish, Tim. "AAD2014: DCNS markets the Mistral 140 in Africa". Shepherd Media. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Saint-Nazaire : Le BPC Dixmude transféré au bassin C". Mer et Marine. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Jean-Michel Roche (2012). "Histoire du BPC Dixmude (2008 - ...)". Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- "L'impressionnante montée en puissance de la flotte égyptienne". 18 April 2016. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "Франция закладывает второй корабль типа "Мистраль" для России". РИА Новости. 18 June 2013. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Второй вертолетоносец типа "Мистраль" спущен на воду во Франции". 20 November 2014. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- "Второй вертолетоносец типа "Мистраль" для России будет спущен на воду в октябре 2014 года". Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Egypt warship: First French-made Mistral ship handed over - BBC News". BBC News. 2 June 2016. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- "Egypt's Sisi inspects southern naval fleet units at Port Safaga". 5 January 2017. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- "France Floats Out First Russian Mistral Warship". RIA Novosti. 15 October 2013. Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "DCNS launch Vladivostok, Russian Navy's first Mistral class LHD(Navy recognition)". 16 October 2013. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- "Egypt to receive second Mistral helicopter carrier on Friday". Archived from the original on 16 September 2016.

Further reading

- Moulin, Jean (2020). Tous les porte-aéronefs en France: de 1912 à nos jours [All the Aircraft Carriers of France: From 1912 to Today]. Collection Navires et Histoire des Marines du Mond; 35 (in French). Le Vigen, France: Lela Presse. ISBN 978-2-37468-035-4.</ref>

External links

- Mistral class (Navy recognition)

- French Marine Nationale - Le BPC, un navire nouvelle génération

- globalsecurity.org

- DCN.fr

- Meretmarine.com

- DCNS