Mission Santa Inés

Mission Santa Inés (sometimes spelled Santa Ynez) was a Spanish mission in the present-day city of Solvang, California, and named after St. Agnes of Rome. Founded on September 17, 1804, by Father Estévan Tapís of the Franciscan order, the mission site was chosen as a midway point between Mission Santa Barbara and Mission La Purísima Concepción, and was designed to relieve overcrowding at those two missions and to serve the Indians living north of the Coast Range. Sunset magazine editors wrote of the Hidden Gem of the Missions: “With its simple, straightforward exterior, Santa Inés fits one’s impression of how a ripe old mission should look.”[10]

.jpg.webp) Mission Santa Inés in 2005 | |

Location in California  Mission Santa Inés (the United States) | |

| Location | 1760 Mission Drive, Solvang, California 93464 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°35′40″N 120°8′13″W |

| Name as founded | La Misión de Nuestra Santa Inés, Virgen y Mártir [1] |

| English translation | The Mission of Saint Agnes of Rome, Virgin and Martyr |

| Patron | Saint Agnes of Rome[2] |

| Nickname(s) | "Hidden Gem of the Missions" [3] |

| Founding date | September 17, 1804 [4] |

| Founding priest(s) | Father Presidente Pedro Estévan Tápis [5] |

| Founding Order | Nineteenth [2] |

| Military district | Second [6] |

| Native tribe(s) Spanish name(s) | Chumash Inéseño |

| Native place name(s) | 'Alahulapu [7] |

| Baptisms | 1,348 [8] |

| Marriages | 400 [8] |

| Burials | 1,227 [8] |

| Secularized | 1836 [2] |

| Returned to the Church | 1862 [2] |

| Governing body | Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles |

| Current use | Parish Church / Museum |

| Reference no. | 99000630[9] |

| Designated | 1999[9] |

| Reference no. |

|

| Website | |

| www | |

The mission was home to the first learning institution in Alta California[5] and today serves as a museum as well as a parish church of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. It is also designated a National Historic Landmark, noted as one of the best-preserved of the 21 California missions.[11]

History

Most of the original church was destroyed on December 21, 1812 in an earthquake centered near Santa Barbara that damaged or destroyed several California missions. The quake also severely damaged other mission buildings, but the complex was not abandoned. A new church, constructed with 5-to-6-foot-thick (1.5 to 1.8 m) walls and great pine beams brought from nearby Figueroa Mountain, was dedicated on July 4, 1817. A water-powered grist mill was built in 1819, about half a mile from the church. In 1821, a fulling mill was added, designed by newly arrived American immigrant Joseph John Chapman.[12] He oversaw the building of a grist mill for Mission San Gabriel, and he prepared timbers for the construction of the first church in Los Angeles. The mill he built near San Gabriel is now a museum. Chapman was baptized at San Buenaventura in 1822, and that same year married Guadalupe Ortega of Santa Barbara, with whom he had five children. In 1824, Chapman bought land in Los Angeles and developed a vineyard, but still continued to perform odd jobs at the missions.

On February 21, 1824 a soldier beat a young Chumash native. Two separate Chumash accounts, written in the early 1900s, state that around the time the tribesman was beaten a Spanish page overheard Santa Inés priests talking about having the natives of the mission killed the next summer when they arrived. The page was found out by the priests after having alerted the natives, and his tongue and feet were cut off before he was burned to death. Upon learning of this news, the natives sought the help of the other Santa Barbara Channel Mission natives and a week later the Chumash revolt of 1824 was sparked.[13] When the fighting was over, the natives themselves put out the fire that had started at the mission. Many of the Indians left to join other tribes in the mountains; only a few Chumash remained at the mission.

In 1833 the missions in California began to be secularized, however, it was not until 1835 that the Santa Inés Mission became secularized by the Mexican government. Secularization involved replacing the padres as managers of the missions with government appointed overseers. In this case, the existing Spanish Franciscans were replaced by Mexican Franciscans who were restricted to provide only for the spiritual needs of the Chumash. The Chumash were mistreated under this new policy and began to leave the mission, returning to their villages or working at settlers’ ranches. As a result, much of their land was given to settlers in land grants.[14]

In 1843, California's Mexican governor Micheltorena granted 34,499 acres (139.61 km2) of Santa Ynez Valley land, called Rancho Cañada de los Pinos, to the College of Our Lady of Refuge, the first seminary in California. Established at the mission by Francisco García Diego y Moreno, the first bishop of California, the college was abandoned in 1881. By then the mission buildings were disintegrating.

Highwayman Jack Powers briefly took over Mission Santa Inés and the adjacent Rancho San Marcos in 1853, intending to rustle the cattle belonging to rancher Nicolas A. Den. Powers was defeated in a bloodless armed confrontation. He was not ousted from the Santa Barbara area until 1855.

The Danish town of Solvang was built up around the mission proper in the early 1900s. It was through the efforts of Father Alexander Buckler in 1904 that reconstruction of the mission was undertaken, though major restoration was not possible until 1947 when the Hearst Foundation donated money to pay for the project. The restoration continues by the Capuchin Franciscan Fathers.

Indigenous people

The Alta California mission system was founded by Catholic priests of the Franciscan order to evangelize the Native Americans. The missionaries introduced European fruits, vegetables, cattle, horses, ranching, and technology. The natives at Santa Inés were used as laborers and the mission's agriculture caused great ecological changes in the environment. Archaeobotanical analysis displayed that the agricultural efforts at Santa Inés are specifically responsible for integrating pea, squash, potato, cabbage, olive, grape, pear, apricot, hemp, peach, carrot, etc. into the environment. It was not long after the placement of the missions that European plants and weeds proliferated throughout California's coast.[15]

Many Natives of missions in the Southwestern region of what is presently U.S. territory and North Mexico fell victim to Euro-Asiatic diseases to which they had no immunity; such as those of the Pimería Alta and Baja California missions. However, demographic studies have shown that the Santa Barbara Channel Missions (Santa Inés, Santa Barbara, San Buenaventura, and La Purísima Concepción) and many other Alta California Missions do not exactly follow this trend. Though the missions were not free of epidemics, the censuses taken in the 1800s display that women and children had a much higher mortality rate than men. Diseases are not partial to gender or age, which meant that something outside of disease had a drastic effect on the Indian population in the missions.

Researchers discovered that the population decline was focused by the unique conditions of the Alta California missions: very tight, overcrowded living arrangements which fostered the spread of diseases. These conditions were met as a part of the program the missions made to culturally and religiously change the Natives. For instance, to control the sexual intercourse of the women, the Franciscans would lock up all the single women together at night in small, damp rooms.[16][17][18]

Restoration of the Mission

The Santa Ines Mission is one of the oldest surviving structures in the state of California and requires constant efforts to repair and restore. Over the years, many men and women have labored in order to preserve, maintain, and restore the historical landmark. Efforts in the past have included restoration of buildings that are made out of adobe (dried mud) to ensure structural stability. The structures made out of adobe are particularly susceptible to the elements, soil shifts, and earthquakes. Without proper conservation, the Santa Ines Mission walls will crack and the artwork will fade.[14]

Parishioners are largely responsible for the efforts put forth in restoring Mission Santa Ines, although, non-parishioners have contributed as well. The parish does not receive state or federal funding, instead they get their funds through museum entrance fees, fundraisers, and donations from individuals and foundations. Individual contributions and grants from private foundations such as the California Mission Foundation has also significantly helped restoration efforts in the past.[14]

Gallery

Mission Santa Inés in about 1912. The mission's original three-bell campanario, erected in 1817, collapsed in a storm in 1911 and was subsequently replaced by this concrete four-bell version, which also had openings on the side. This tower was replaced in 1948 to restore the original three-niched appearance. It has been compared by architectural historian Rexford Newcomb to the one that originally abutted the façade of Mission San Gabriel Arcángel.

Mission Santa Inés in about 1912. The mission's original three-bell campanario, erected in 1817, collapsed in a storm in 1911 and was subsequently replaced by this concrete four-bell version, which also had openings on the side. This tower was replaced in 1948 to restore the original three-niched appearance. It has been compared by architectural historian Rexford Newcomb to the one that originally abutted the façade of Mission San Gabriel Arcángel. Santa Ines marker

Santa Ines marker Santa Ines 1982

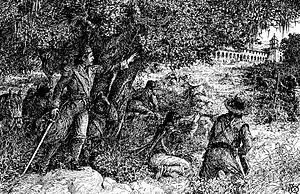

Santa Ines 1982 Mexican soldiers advancing toward La Purísima Concepción Mission during the Chumash revolt of 1824. Painting by Alexander Harmer.

Mexican soldiers advancing toward La Purísima Concepción Mission during the Chumash revolt of 1824. Painting by Alexander Harmer.

See also

References

- Leffingwell, p. 71

- Krell, p. 286

- Ruscin, p. 163

- Yenne, p. 164

- Ruscin, p. 196

- Forbes, p. 202

- Ruscin, p. 195

- Krell, p. 315: as of December 31, 1832; information adapted from Engelhardt's Missions and Missionaries of California.

- NHL Admission

- Sunset Travel Guide to Southern California. Menlo Park, Calif.: Lane Publishing Co. 1974. p. 152. SBN 376-06754-3.

- "NHL nomination for Mission Santa Ines". National Park Service. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- Santa Inés Mission Mills | A Brief History Archived 2014-02-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Hudson, Travis (Summer 1980). "The Chumash Revolt of 1824: Another Native Account From the Notes of John P. Harrington". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 2 (1): 123–126. JSTOR 27825004.

- "History of the Chumash People". www.santaynezchumash.org. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- Allen, Rebecca (2010). "Alta California Missions and the Pre-1849 Transformation of Coastal Lands". Historical Archaeology. 44 (3): 69–80. doi:10.1007/BF03376804. S2CID 161106660.

- Jackson, Robert H. (1992). "Patterns of Demographic Change in the Alta California Missions: The Case of Santa Ines". California History. 71 (3): 362–369. doi:10.2307/25158649. JSTOR 25158649.

- Jackson, Robert H. (1990). "The Population of the Santa Barbara Channel Missions (Alta California), 1813-1832". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 12: 268–274.

- Jackson, Robert H. (1981). "The Last Jesuit Censuses of the Pimería Alta Missions, 1761 and 1766". Kiva. 46 (4): 243–272. doi:10.1080/00231940.1981.11757959. PMID 11632438.

Sources

- Forbes, Alexander (1839). California: A History of Upper and Lower California. Smith, Elder and Co., Cornhill, London.

- Krell, Dorothy, ed. (1979). The California Missions: A Pictorial History. Sunset Publishing Corporation, Menlo Park, CA. ISBN 978-0-376-05172-1.

- Jones, Terry L.; Klar, Kathryn A., eds. (2007). California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity. Altimira Press, Landham, MD. ISBN 978-0-7591-0872-1.

- Leffingwell, Randy (2005). California Missions and Presidios: The History & Beauty of the Spanish Missions. Voyageur Press, Inc., Stillwater, MN. ISBN 978-0-89658-492-1.

- Paddison, Joshua, ed. (1999). A World Transformed: Firsthand Accounts of California Before the Gold Rush. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA. ISBN 978-1-890771-13-3.

- Ruscin, Terry (1999). Mission Memoirs. Sunbelt Publications, San Diego, CA. ISBN 978-0-932653-30-7.

- Yenne, Bill (2004). The Missions of California. Thunder Bay Press, San Diego, CA. ISBN 978-1-59223-319-9.

External links

- Official Mission Santa Inés website

- Early photographs, sketches, land surveys of Mission Santa Inés, via Calisphere, California Digital Library

- Elevation & Site Layout sketches of the Mission proper