Chinese treasure ship

A Chinese treasure ship (simplified Chinese: 宝船; traditional Chinese: 寶船; pinyin: bǎochuán, literally "gem ship"[14]) is a type of large wooden ship in the fleet of admiral Zheng He, who led seven voyages during the early 15th-century Ming dynasty. The size of the Chinese treasure ship has been a subject of debate with the Chinese records mentioning the size of 44 zhang or 44.4 zhang, which has been interpreted by some as over 100 m (330 ft) in length, while others have stated that Zheng He's largest ship was about 70 m (230 ft) or less in length.[15]

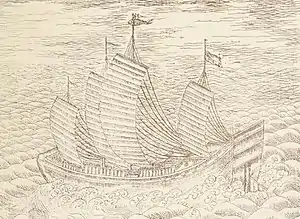

Sketch of four-masted Zheng He's ship | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | 2,000 liao da bo (lit. large ship), hai po, hai chuan (lit. sea going ship) |

| Ordered | 1403 |

| Builder | Longjiang shipyards, Ming dynasty |

| In service | 1405 |

| Out of service | 1433 |

| Notes | Participated in:

|

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Armed merchant ship[1] |

| Displacement | 800 tons |

| Tons burthen | 500 tons |

| Length | 166 ft (50.60 m) |

| Beam | 24.3 ft (7.41 m) |

| Draught | 8.1 ft (2.47 m) |

| Propulsion | 4 masts[2] |

| Sail plan | Junk rig |

| Complement | 200–300 person[3] |

| Armament | 24 cannons[4] |

| Notes | References: Tonnages,[5] dimensions[6] |

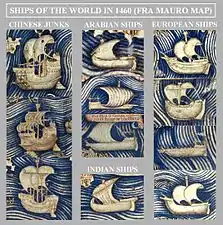

Early 17th century Chinese woodblock print, thought to represent Zheng He's ships. The ships are depicted with 7 masts, but only 4 sails used. | |

| History | |

| Name | 5,000 liao ju bo (lit. giant ship), baochuan (lit. gem ship) |

| Ordered | Before 1412 |

| Builder | Longjiang shipyards, Ming dynasty |

| In service | 1412 |

| Out of service | 1433 |

| Notes | Participated in:

|

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Armed merchant ship[1] |

| Displacement | 3100 tons |

| Tons burthen | 1860 tons |

| Length | 71.1 m (233.3 ft) |

| Beam | 14.05 m (46.1 ft) |

| Draught | 6.1 m (20.0 ft) |

| Propulsion | 6–7 masts[7][8] |

| Sail plan | Junk rig |

| Complement | 500–600 person[9][10] |

| Armament | 24 cannons[4] |

| Notes | References: Voyages,[11] tonnages,[12] dimensions[13] |

Accounts

Chinese

According to the Guoque (1658), the first voyage consisted of 63 treasure ships crewed by 27,870 men.[16]

The History of Ming (1739) credits the first voyage with 62 treasure ships crewed by 27,800 men.[16] A Zheng He era inscription in the Jinghai Temple in Nanjing gave the size of Zheng He ships in 1405 as 2,000 liao (500 tons), but did not give the number of ships.[17]

Alongside the treasures were also another 255 ships according to the Shuyu Zhouzilu (1520), giving the combined fleet of the first voyage a total of 317 ships. However, the addition of 255 ships is a case of double accounting according to Edward L. Dreyer, who notes that the Taizong Shilu does not distinguish the order of 250 ships from the treasure ships. As such the first fleet would have been around 250 ships including the treasure ships.[16]

The second voyage consisted of 249 ships.[18] The Jinghai Temple inscription gave the ship dimensions in 1409 as 1500 liao (375 tons).[16]

According to the Xingcha Shenglan (1436), the third voyage consisted of 48 treasure ships, not including other ships.[16]

The Xingcha Shenglan states that the fourth voyage consisted of 63 treasure ships crewed by 27,670 men.[19]

There are no sources for number of ships or men for the fifth and sixth voyages.[19]

According to the Liujiagang and Changle Inscriptions, the seventh voyage had "more than a hundred large ships".[19]

Yemen

The most contemporary non-Chinese record of the expeditions is an untitled and anonymous annalistic account of the then-ruling Rasūlid dynasty of Yemen, compiled in the years 1439–1440. It reports the arrival of Chinese ships in 1419, 1423, and 1432, which approximately correspond to Zheng He's fifth, sixth, and seventh voyages. The 1419 arrival is described thus:

Arrival of Dragon-ships [marākib al-zank] in the protected harbour city [of Aden] and with them the messengers of the ruler of China with brilliant gifts for his Majesty, the Sultan al-Malik al-Nāsir in the month of l’Hijja in the year 821 [January 1419]. His Majesty, the Sultan al-Malik al-Nāsiṛ’s in the Protected Dār al-Jund send the victorious al-Mahaṭṭa to accept the brilliant gifts of the ruler of China. It was a splendid present consisting of all manner of rarities [tuhaf], splendid Chinese silk cloth woven with gold [al-thiyāb al-kamkhāt al-mudhahhabah], top quality musk, storax [al-ʾūd al-ratḅ] and many kinds of chinaware vessels, the present being valued at twenty thousand Chinese mithqāl [93.6 kg gold]. It was accompanied by the Qādi Wajīh al-Dīn ʿAbd al-Rahman b. Jumay. And this was on 26 Muharram in the year 822 [March 19, 1419]. His majesty, the Sultan al-Malik al-Nāsir ordered that the Envoy of the ruler of China [rusul sāhib al-Sị̄n] returned with gifts of his own, including many rare, with frankincense wrapped coral trees, wild animals such as Oryx, wild ass, thousands of wild lion and tamed cheetahs. And they travelled in the company of Qādi Wajīh al-Dīn ʿAbd al-Rahman b. Jumay out of the sheltered harbour of Aden in the month of Safar of the year 822 [March 1419].[20][21]

The later Yemeni historian, Ibn al-Daybaʿ (1461–1537), writes:

[The Chinese arrived at Aden in 1420 on] great vessels containing precious gifts, the value of which was twenty lacs [sic; lakhs] of gold... [Zheng He] had an audience with al-Malik al-Nāsir without kissing the ground in front of him, and said:

"Your Master the Lord of China [sāhib al-Sị̄n] greets you and counsels you to act justly to your subjects.”

And he [al-Malik al-Nāsir] said to him: "Welcome, and how nice of you to come!”

And he entertained him and settled him in the guesthouse. Al-Nāsir wrote a letter to the Lord of China:

"Yours it is to command and [my] country is your country."

He dispatched to him wild animals and splendid sultanic robes, an abundant quality, and ordered him to be escorted to the city of Aden.[21][22]

Mamluks

Mamluk historian Ibn Taghribirdi (1411–1470) writes:

Shawwāl 22 [21 June 1432 CE]. A report came from Mecca the Honored that a number of junks had come from China to the seaports of India, and two of them had anchored in the port of Aden, but their goods, chinaware, silk, musk, and the like, were not disposed of there because of the disorder of the state of Yemen. The captains of these two junks wrote to the Sharīf Barakāt ibn Hasan ibn ʿAjlān, emir of Mecca, and to Saʾd al-Dīn Ibrāhīm ibn al-Marra, controller of Judda [Jeddah], asking permission to come to Judda. The two wrote to the Sultan about this, and made him eager for the large amount [of money] that would result if they came. The Sultan wrote to them to let them come to Judda, and to show them honor.[23]

Niccolò de' Conti

Niccolò de' Conti (c. 1395–1469), a contemporary of Zheng He, was also an eyewitness of Chinese ships in Southeast Asia, claiming to have seen five-masted junks of about 2000 tons* burthen:[24]

They doe make bigger Shippes than wee do, that is to say, of 2000 tons, with five sayles, and so many mastes'.[25]

— Niccolò Da Conti

- Other translations of the passage give the size as a 2000 butts,[26] which would be around a 1000 tons, a butt being half a ton.[note 1] Christopher Wake noted that the transcription of the unit is actually vegetes, that is Venetian butt, and estimated a burthen of 1300 tons.[27] The ship of Conti may have been a Burmese or Indonesian jong.[28]

Song and Yuan junks

Although active prior to the treasure voyages, both Marco Polo (1254–1325) and Ibn Battuta (1304–1369) attest to large multi-masted ships carrying 500 to 1000 passengers in Chinese waters.[29] The large ships (up to 5,000 liao or 1520–1860 tons burden) would carry 500–600 men, and the second class (1,000–2,000 liao) would carry 200–300 men.[14] Unlike Ming treasure ships, Song and Yuan great junks were propelled by oars, and have with them smaller junks, probably for maneuvering aids.[30] The largest junks (5,000 liao) may have had a hull length twice that of Quanzhou ship (1,000 liao),[31] that is 68 m (223.1 ft).[14] However, the usual Chinese trading junks pre-1500 was around 20–30 m (65.6–98.4 ft) long, with the length of 30 m (98.4 ft) only becoming the norm after 1500 CE. Large size could be a disadvantage for shallow harbors of southern seas, and the presence of numerous reefs exacerbates this.[32]

Marco Polo

I tell you that they are mostly built of the wood which is called fir or pine.

They have one floor, which with us is called a deck, one for each, and on this deck there are commonly in all the greater number quite 60 little rooms or cabins, and in some, more, and in some, fewer, according as the ships are larger and smaller, where, in each, a merchant can stay comfortably.

They have one good sweep or helm, which in the vulgar tongue is called a rudder.

And four masts and four sails, and they often add to them two masts more, which are raised and put away every time they wish, with two sails, according to the state of the weather.

Some ships, namely those which are larger, have besides quite 13 holds, that is, divisions, on the inside, made with strong planks fitted together, so that if by accident that the ship is staved in any place, namely that either it strikes on a rock, or a whale-fish striking against it in search of food staves it in... And then the water entering through the hole runs to the bilge, which never remains occupied with any things. And then the sailors find out where the ship is staved, and then the hold which answers to the break is emptied into others, for the water cannot pass from one hold to another, so strongly are they shut in; and then they repair the ship there, and put back there the goods which had been taken out.

They are indeed nailed in such a way; for they are all lined, that is, that they have two boards above the other.

And the boards of the ship, inside and outside, are thus fitted together, that is, they are, in the common speech of our sailors, caulked both outside and inside, and they are well nailed inside and outside with iron pins. They are not pitched with pitch, because they have none of it in those regions, but they oil them in such a way as I shall tell you, because they have another thing which seems to them to be better than pitch. For I tell you that they take lime, and hemp chopped small, and they pound it all together, mixed with an oil from a tree. And after they have pounded them well, these three things together, I tell you that it becomes sticky and holds like birdlime. And with this thing they smear their ships, and this is worth quite as much as pitch.

Moreover I tell you that these ships want some 300 sailors, some 200, some 150, some more, some fewer, according as the ships are larger and smaller.

They also carry a much greater burden than ours.[33]— Marco Polo

Ibn Battuta

People sail on the China seas only in Chinese ships, so let us mention the order observed upon them.

There are three kinds: the greatest is called 'jonouq', or, in the singular, 'jonq' (certainly chuan); the middling sized is a 'zaw' (probably sao); and the least a 'kakam'.

A single one of the greater ships carries 12 sails, and the smaller ones only three. The sails of these vessels are made of strips of bamboo, woven into the form of matting. The sailors never lower them (while sailing, but simply) change the direction of them according to whether the wind is blowing from one side or the other. When the ships cast anchor, the sails are left standing in the wind...

These vessels are nowhere made except in the city of Zaytong (Quanzhou) in China, or at Sin-Kilan, which is the same as Sin al-Sin (Guangdong).

This is the manner after which they are made; two (parallel) walls of very thick wooden (planking) are raised, and across the space between them are placed very thick planks (the bulkheads) secured longitudinally and transversely by means of large nails, each three ells in length. When these walls have thus been built, the lower deck is fitted in, and the ship is launched before the upper works are finished.

The pieces of wood, and those parts of the hull, near the water (-line) serve for the crew to wash and to accomplish their natural necessities.

On the sides of these pieces of wood also the oars are found; they are as big as masts, and are worked by 10 to 15 men (each), who row standing up.

The vessels have four decks, upon which there are cabins and saloons for merchants. Several of these 'misriya' contain cupboards and other conveniences; they have doors which can be locked, and keys for their occupiers. (The merchants) take with them their wives and concubines. It often happens that a man can be in his cabin without others on board realising it, and they do not see him until the vessel has arrived in some port.

The sailors also have their children in such cabins; and (in some parts of the ship) they sow garden herbs, vegetables, and ginger in wooden tubs.

The Commander of such a vessel is a great Emir; when he lands, the archers and the Ethiops march before him bearing javelins and swords, with drums beating and trumpets blowing. When he arrives at the guesthouse where he is to stay, they set up their lances on each side of the gate, and mount guard throughout his visit.

Among the inhabitants of China there are those who own numerous ships, on which they send their agents to foreign places. For nowhere in the world are there to be found people richer than the Chinese.[34]— Ibn Battuta

Description

Taizong Shilu

The most contemporary accounts of the treasure ships come from the Taizong Shilu, which contains 24 notices from 1403 to 1419 for the construction of ships at several locations.[35]

On 4 September 1403, 200 "seagoing transport ships" were ordered from the Capital Guards in Nanjing.[36]

On 1 March 1404, 50 "seagoing ships" were ordered from the Capital Guards.[36]

In 1407, 249 vessels were ordered "to be prepared for embassies to the several countries of the Western Ocean".[35]

On 14 February 1408, 48 treasure ships were ordered from the Ministry of Works in Nanjing. This is the only contemporary account containing references to both treasure ships and a specific place of construction. Coincidentally, the only physical evidence of treasure ships comes from Nanjing.[37]

On 2 October 1419, 41 treasure ships were ordered without disclosing the specific builders involved.[35]

Longjiang Chuanchang Zhi

Li Zhaoxiang's Longjiang Chuanchang Zhi (1553), also known as the Record of the Dragon River Shipyard, notes that the plans for the treasure ships had vanished from the ship yard in which they were built.[38]

Sanbao Taijian Xia Xiyang Ji Tongsu Yanyi

According to Luo Maodeng's 1597 novel Sanbao Taijian Xia Xiyang Ji Tongsu Yanyi (Eunuch Sanbao Western Records Popular Romance), the treasure fleet consisted of five distinct classes of ships:[39][35][40]

- Treasure ships (宝船, Bǎo Chuán) nine-masted, 44.4 by 18 zhang, about 127 metres (417 feet) long and 52 metres (171 feet) wide.

- Equine ships (馬船, Mǎ Chuán), carrying horses and tribute goods and repair material for the fleet, eight-masted, 37 by 15 zhang, about 103 m (338 ft) long and 42 m (138 ft) wide.

- Supply ships (粮船, Liáng Chuán), containing staple for the crew, seven-masted, 28 by 12 zhang, about 78 m (256 ft) long and 35 m (115 ft) wide.

- Transport ships (坐船, Zuò Chuán), six-masted, 24 by 9.4 zhang, about 67 m (220 ft) long and 25 m (82 ft) wide.

- Warships (战船, Zhàn Chuán), five-masted, 18 by 6.8 zhang, about 50 m (160 ft) long.

Edward L. Dreyer claims that Luo Maodeng's novel is unsuitable as historical evidence.[35] The novel contains a number of fantasy element; for example the ships were "constructed with divine help by the immortal Lu Ban".[41] Scholars have worked, however, to distinguish the fictional elements from those that the author had access to but have subsequently been lost, including both written and oral sources.[42]

Dimensions and size

Contemporary descriptions

The contemporary inscription of Zheng He's ships in the Jinghai temple (靜海寺—Jìng hǎi sì) inscription in Nanjing gives sizes of 2,000 liao (500 tons) and 1,500 liao (275 tons),[17] which are far too low than would be implied by a ship of 444 chi (450 ft) given by the History of Ming. In addition, in the contemporary account of Zheng He's 7th voyage by Gong Zhen, he said it took 200 to 300 men to handle Zheng He's ships. Ming minister Song Li indicated a ratio of 1 man per 2.5 tons of cargo, which would imply Zheng He's ships were 500 to 750 tons.[3]

The inscription on the tomb of Hong Bao, an official in Zheng He's fleet, mentions the construction of a 5,000 liao displacement ship.[43]

History of Ming

According to the History of Ming (Ming shi—明史), completed in 1739, the treasure ships were 44 zhang, 4 chi, i.e. 444 chi in length, and had a beam of 18 zhang. The dimensions of ships are no coincidence. The number "4" has numerological significance as a symbol of the 4 cardinal directions, 4 seasons, and 4 virtues. The number 4 was an auspicious association for treasure ships.[44] These dimensions first appeared in a novel published in 1597, more than a century and a half after Zheng He's voyages. The 3 contemporary accounts of Zheng He's voyages do not have the ship dimensions.[45]

The zhang was fixed at 141 inches in the 19th century, making the chi 14.1 inches. However the common Ming value for chi was 12.2 inches and the value fluctuated depending on region. The Ministry of Works used a chi of 12.1 inches while the Jiangsu builders used a chi of 13.3 inches. Some of the ships in the treasure fleet, but not the treasure ships, were built in Fujian, where the chi was 10.4 to 11 inches. Assuming a range of 10.5 to 12 inches for each chi, the dimensions of the treasure ships as recorded by the History of Ming would have been between 385 by 157.5 feet and 440 by 180 feet (117.5 by 48 metres, and 134 by 55 metres).[46] Louise Levathes estimates that it had a maximum size of 110–124 m (390–408 feet) long and 49–51 m (160–166 feet) wide instead, taking 1 chi as 10.53–11.037 inches.[44]

According to British scientist, historian and sinologist Joseph Needham, the dimensions of the largest of these ships were 135 metres (440 ft) by 55 metres (180 ft).[47] American historian Edward L. Dreyer is in broad agreement with Needham's views.[48]

Modern estimates

Modern scholars have argued on engineering grounds that it is highly unlikely that Zheng He's ship was 450 feet (137 m) in length. Guan Jincheng (1947) proposed a much more modest size of 20 zhang long by 2.4 zhang wide (204 ft by 25.5 ft or 62.2 m by 7.8 m).[49] Xin Yuan'ou, a shipbuilding engineer and professor of the history of science at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, argues on engineering grounds that it is highly unlikely that Zheng He's treasure ships were 450 ft long, and suggests that they were probably closer to 200–250 ft (61–76 m) in length.[50][5] Hsu Yun-Ts'iao does not agree with Xin Yuan'ou: Estimating the size of a 2,000 liao ship with the Treatise of the Longjiang shipyard (龙江船厂志—lóng jiāng chuánchǎng zhì) at Nanjing, the size is as follows: LOA 166 ft (50.60 m), bottom's hull length 102.6 ft (31.27 m), overhanging "tail" length 23.4 ft (7.13 m), front depth 6.9 ft (2.10 m), front width 19.5 ft (5.94 m), mid-hull depth 8.1 ft (2.47 m), mid-hull width 24.3 ft (7.41 m), tail depth 12 ft (3.66 m), tail width 21.6 ft (6.58 m), and the length to width ratio is 7:1.[6] Dionisius A. Agius (2008) estimated a size of 200–250 ft (60.96 m–76.2 m) and maximum weight of 700 tons.[51] Tang Zhiba, Xin Yuan'ou, and Zheng Ming have calculated the dimensions of the 2,000 liao ship, obtaining a length of 61.2 m (200.79 ft), width of 13.8 m (45.28 ft), and draught of 3.9 m (12.80 ft).[52] Zheng Ming believes that the "Heavenly Princess Classics" depict 2,000 liao ships.[13]

André Wegener Sleeswyk extrapolated the size of liao (料 — material) by deducing the data from mid-16th century Chinese river junks. He suggested that the 2,000 liao ships were bao chuan (treasure ship), while the 1,500 liao ships were ma chuan (horse ship). In his calculations, the treasure ships would have had a length of 52.5 m, a width of 9.89 m, and a height of 4.71 m. The horse ships would have a length of 46.63 m, a width of 8.8 m, and a height of 4.19 m.[53] Richard Barker estimated that the treasure ships would have a length of 230 ft (70.10 m), a width of 65 ft (19.81 m), and a draught of 20 ft (6.10 m). He estimated it using an assumed displacement of 3100 tons.[54]

One explanation for the colossal size of the 44 zhang treasure ships, if in fact built, was that they were only for a display of imperial power by the emperor and imperial bureaucrats on the Yangtze River when on court business, including when reviewing Zheng He's actual expedition fleet. The Yangtze River, with its calmer waters, may have been navigable for such large but unseaworthy ships. Zheng He would not have had the privilege in rank to command the largest of these ships. Some of the largest ships of Zheng He's fleet were the 6 masted 2000-liao ships. This would give burthen of 500 tons and a displacement tonnage of about 800 tons.[5][55] Because they were built and based in Nanjing, and repeatedly sailed along the Yangtze river (including in winter, when the water is low), their draught cannot exceed 7–7.5 m. It is also known that Zheng He's fleet visited Palembang in Sumatra, where they needed to cross the Musi river. It is unknown whether Zheng He's ships sailed as far as Palembang, or whether they waited on the shore in the Bangka Strait while the smaller ships sailed at Musi; but at least the draught of the ship that reaches Palembang should not be more than 6 m.[56]

Xin Yuan'ou argued that Zheng He's ships could not have been as large as recorded in the History of Ming.[50] based on the following reasons:

- Ships of the dimensions given in the Ming shi would have been 15,000–20,000 tons according to his calculations, exceeding a natural limit to the size of a wooden ocean-going ship of about 7,000 tons displacement.[57]

- With the benefit of modern technology it would be difficult to manufacture a wooden ship of 10,000 tons, let alone one that was 1.5–2 times that size. It was only when ships began to be built of iron in the 1860s that they could exceed 10,000 tons.[57]

- Watertight compartments characteristic of traditional Chinese ships tended to make the vessels transversely strong but longitudinally weak.[57][58]

- A ship of these dimensions would need masts that were 100 metres tall. Several timbers would have to be joined vertically. As a single tree trunk would not be large enough in diameter to support such mast, multiple timbers would need to be combined at the base as well. No evidence that China had the type of joining materials necessary to accomplish these tasks.[58][57]

- A ship with 9 masts would be unable to resist the combined strength and force of such huge sails, she would not be able to cope with strong wind and would break.[59]

- It took four centuries (from the Renaissance era to the early premodern era) for Western ships to increase in size from 1500 to 5000 tons displacement. For Chinese ships to have reached three or four times this size in just two years (from Emperor Yongle's accession in 1403 to the launch of the first expedition in 1405) was unlikely.[57]

- 200–300 sailor as mentioned by Gong Zhen could not have managed a 20,000 tons ship. According to Xin, a ship of such size would have a complement of 8,000 men.[60]

From the comments of modern scholars on Medieval Chinese accounts and reports, it is apparent that a ship had a natural limit to her size, going beyond, would have made her structurally unsafe as well as causing a considerable loss of maneuverability, something the Spanish Armada ships famously experienced.[61] Beyond a certain size (about 300 feet or 91.44 m in length) a wooden ship is structurally unsafe.[62] It was not until the mid to late 19th century that the length of the largest western wooden ship began to exceed 100 meters, even this was done using modern industrial tools and iron parts.[63][64][65]

Measurement conversion

It is also possible that the measure of zhang (丈) used in the conversions was mistaken. Seventeenth-century Ming records state that the European East Indiamen and galleons were 30, 40, 50, and 60 zhang (90, 120, 150, and 180 m) in length.[66] The length of a Dutch ship recorded in the History of Ming was 30 zhang. If the zhang is taken to be 3.2 m, the Dutch ship would be 96 m long. Also, the Dutch Hongyi cannon was recorded to be more than 2 zhang (6.4 m) long. A comparative study by Hu Xiaowei (2018) concluded that 1 zhang would be equal to 1.5–1.6 m, this means the Dutch ship would be 45–48 m long and the cannon would be 3–3.2 m long.[67] Taking 1.6 m for 1 zhang, Zheng He's 44 zhang treasure ship would be 70.4 m (230.97 ft) long and 28.8 m (94.49 ft) wide, or 22 zhang long and 9 zhang wide if the zhang is taken to be 3.2 m.[68] It is known that the measuring unit during the Ming era was not unified: A measurement of East and West Pagoda in Quanzhou resulted in a zhang unit of 2.5–2.56 m.[69] According to Chen Cunren, one zhang in the Ming Dynasty is only half a zhang in modern times.[70]

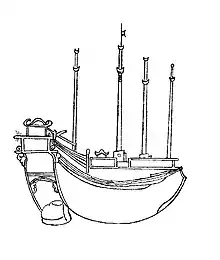

5,000 liao ship

In June 2010, a new inscription was found in Hong Bao's tomb, confirming the existence of the Ming dynasty's 5,000 liao ship.[71][43] Taking the liao to be 500 lb (226.80 kg) burthen, that would be 1,250 tons burthen.[55] Sleeswyk argued that the term liao refers to the displacement and not cargo weight, one liao would be equivalent to 500 kg (1,102.31 lb) of displacement.[72] According to Zheng Ming, the 5,000 liao ship would have a dimension of 71.1 m (233.27 ft), width of 14.05 m (46.10 ft), with 6.1 m (20.01 ft) draught, and the displacement would reach more than 2,700 tons. The 5,000 liao ship may have been used as the flagship but the number of ships was relatively small.[13] Wake argued that the 5,000 liao ships were not used until after the 3rd voyage, when the voyages were extended beyond India.[11] Xi Longfei identified that the word "treasure ship", which would refer to the 44 zhang ship, appeared for the first time in the 6th year of Yongle. This large ship was too late to be used for the third voyage, so it appeared for the first time during the 4th voyage, and was recorded by Ma Huan.[73] Judging from the three images from the Ming era, the largest ships had 3–4 main masts and 2–3 auxiliary masts.[52]

Structure

The keel consisted of wooden beams bound together with iron hoops. In stormy weather, holes in the prow would partially fill with water when the ship pitched forward, thus lessening the violent turbulence caused by waves. Treasure ships also used floating anchors cast off the sides of the ship in order to increase stability. The stern had two 2.5 m (8 foot) iron anchors weighing over a thousand pounds each, used for mooring offshore. Like many Chinese anchors, these had four flukes set at a sharp angle against the main shaft. Watertight compartments were also used to add strength to the treasure ships. The ships also had a balanced rudder which could be raised and lowered, creating additional stability like an extra keel. The balanced rudder placed as much of the rudder forward of the stern post as behind it, making such large ships easier to steer. Unlike a typical fuchuan warship, the treasure ships had nine staggered masts and twelve square sails, increasing its speed. Treasure ships also had 24 cast-bronze cannons with a maximum range of 240 to 275 m (800–900 feet). However, treasure ships were considered luxury ships rather than warships. As such, they lacked the fuchuan's raised platforms or extended planks used for battle.[4]

Non-gunpowder weapons on Zheng He's vessels seems to be bows. For gunpowder weapons, they carried bombards (albeit shorter than Portuguese bombards) and various kind of hand cannons, such as can be found on early 15th century Bakau shipwreck.[74][75] Comparing with Penglai wrecks, the fleet may have carried cannons with bowl-shaped muzzle (which dates back to late Yuan dynasty), and iron cannons with several rings on their muzzle (in the wrecks they are 76 and 73 cm long, weighing 110 and 74 kg), which according to Tang Zhiba, a typical of early Ming iron cannon. They may also carry incendiary bombs (quicklime bottles).[76] Girolamo Sernigi (1499) gives an account of the armament of what possibly the Chinese vessels:

It is now about 80 years since there arrived in this city of Chalicut certain vessels of white Christians, who wore their hair long like Germans, and had no beards except around the mouth, such as are worn at Constantinople by cavaliers and courtiers. They landed, wearing a cuirass, helmet, and visor, and carrying a certain weapon [sword] attached to a spear. Their vessels are armed with bombards, shorter than those in use with us. Once every two years they return with 20 or 25 vessels. They are unable to tell what people they are, nor what merchandise they bring to this city, save that it includes very fine linen-cloth and brass-ware. They load spices. Their vessels have four masts like those of Spain. If they were Germans it seems to me that we should have had some notice about them; possibly they may be Russians if they have a port there. On the arrival of the captain we may learn who these people are, for the Italian-speaking pilot, who was given him by the Moorish king, and whom he took away contrary to his inclinations, is with him, and may be able to tell.

— Girolamo Sernigi (1499) about the then-unknown Chinese visitors [77]

Physical evidence

From 2003 to 2004, the Treasure Shipyard was excavated in northwestern Nanjing (the former capital of the Ming Dynasty), near the Yangtze River. Despite the site being referred to as the "Longjiang Treasure Shipyard" (龍江寶船廠—lóng jiāng bǎo chuánchǎng) in the official names, the site is distinct from the actual Longjiang Shipyard, which was located on a different site and produced different types of ships. The Treasure Shipyard, where Zheng He's fleet were believed to have been built in the Ming Dynasty, once consisted of thirteen basins (based on a 1944 map), most of which have now been covered by the construction of buildings in the 20th century. The basins are believed to have been connected to the Yangtze via a series of gates. Three long basins survive, each with wooden structures inside them that were interpreted to be frames for the ships to be built on. The largest basin extends for a length of 421 metres (1,381 ft). While they were long enough to accommodate the largest claimed Zheng He treasure ship, they were not wide enough to fit even a ship half the claimed size. The basin was only 41 metres (135 ft) wide at most, with only a 10 metres (33 ft) width area of it showing evidence of structures. They were also not deep enough, being only 4 metres (13 ft) deep. Other remains of ships in the site indicate that the ships were only slightly larger than the frames that supported them. Moreover, the basin structures were grouped into clusters with large gaps between them, if each cluster was interpreted as a ship framework, then the largest ship would not exceed 75 metres (246 ft) at most, probably less.[78]

In 1957, a large 11-meter-long rudder shaft was discovered during excavations at the Treasure shipyards. The rudder blade, which did not survive, was attached to a 6-meter section of the axis. According to Chinese archaeologists, the area of the rudder was approximately 42.5 m², and the length of the ship to which it belonged was estimated at 149–166 meters.[79][80][note 2] However, such use of this piece of archeological evidence rests upon supposing proportions between the rudder and the length of the ship, which have also been the object of intense contestation: That length was estimated using steel, engine-driven ship as the reference. By comparing the rudder shaft to the Quanzhou ship, Church estimated that the ship was 150 ft (45.72 m) long.[82]

Speed

The treasure ships were different in size, but not in speed. Under favorable conditions, such as sailing with the winter monsoon from Fujian to Southeast Asia, Zheng He's fleet developed an average speed of about 2.5 knots (4.63 km/h); on many other segments of his route, a significantly lower average speed was recorded, of the order of 1.4–1.8 knots (2.59–3.33 km/h).[83]

As historians note, these speeds were relatively low by the standards of later European sailing fleets, even in comparison with ship of the line, which were built with an emphasis on armament rather than speed. For example, in 1809, Admiral Nelson's squadron, consisting of 10 ships of the line, crossed the Atlantic Ocean at an average speed of 4.9 knots (9.07 km/h).[84]

Replica

A 71.1-metre (233.3 ft) copy of a treasure ship was announced in 2006 to be completed in time for the 2008 Olympic Games.[85] However, the copy was still under construction in Nanjing in 2010.[86] A new date of completion was set for 2013;[87] when this dateline failed to be met in 2014, the project was built for 4 years.[88]

See also

- List of world's largest wooden ships

- Jong (ship), Javanese ship, those used by Majapahit were larger than baochuan

- Grace Dieu (ship), English flagship of Henry V, about the same size as baochuan

- Ancient Chinese wooden architecture

- Pagoda of Fogong Temple

Notes

- See definition of butt https://gizmodo.com/butt-is-an-actual-unit-of-measurement-1622427091. Until the 17th century, ton referred to both the unit of weight and the unit of volume — see https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/ton. A tun is 252 gallons, which weighs 2092 lbs, which is around a ton.

- Dreyer estimated the length of between 538 and 600 feet (163.98 and 182.88 m) for the ship.[81]

References

Citations

- Lo 2012, p. 114.

- Wake, June 2004: 63, quoting Guan Jincheng, 15 January 1947: 49

- Church 2005, p. 16.

- Levathes 1994, p. 81-82.

- Xin Yuan'ou (2002). Guanyu Zheng He baochuan chidu de jishu fenxi [A Technical Analysis of the Size of Zheng He's Ships]. Shanghai. p. 8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Suryadinata 2005, p. 135.

- Depiction on the 天妃经 (Tian Fei Jing) or "Heavenly Princess Classics" from ca. 1420, which depicted ships with six masts.

- Depiction on the 17th century woodblock print

- Mills 1970, p. 2.

- Finlay 1992, p. 227.

- Wake 2004, p. 74.

- Wake 2004, p. 64, 75.

- Ming 2011, p. 15.

- Wake 2004, p. 75.

- Ling, Xue (July 12, 2022). Li, Ma; Limin, Wu; Xiuling, Pei (eds.). "郑和大号宝船到底有多大? (How big was Zheng He's large treasure ship?)" (PDF). 扬子晚报 (Yangtze Evening News).

- Dreyer 2007, p. 123.

- Church 2005, p. 10.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 124.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 126.

- Sen 2016, p. 619.

- Hikoichi Yajima (1974). A Facet of the Commercial Interactions in the Indian Ocean during the 15th Century: On the Visit of a Division from Zheng He's Expedition to Yemen.

- Sen 2016, p. 620.

- Yūsuf Ibn Taġrībardī (1954–1963). History of Egypt 1382–1469. Translated by William Popper. Berkeley: University of California Press, translated from the Arabic annals of Abu l-Maḥāsin Ibn Taghrī Birdī.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Needham 1971, p. 452.

- Needham 1971, p. 468.

- Major, R. H., ed. (1857), "The travels of Niccolo Conti", India in the Fifteenth Century, Hakluyt Society, p. 27

- Wake 1997, p. 58.

- Lewis 1973, p. 248.

- Needham 1971, pp. 460–470.

- Wake 1997, pp. 57, 67.

- Wake 1997, pp. 66–67.

- Bowring 2019, p. 128-129.

- Needham 1971, p. 466.

- Needham 1971, pp. 469–470.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 104.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 105.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 104-105.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 220.

- Church 2005, p. 6.

- 京 (Jing), 安 (An) (2012). 海疆开发史话 (History of Coastal Development). 社会科学文献出版社 (Social Science Literature Press). p. 98. ISBN 978-7-5097-3196-3. OCLC 886189859.

- Church 2005, p. 7.

- Barbara Witt, "Introduction: Sanbao Taijian Xiyang Ji Tongsu Yanyi:: An Annotated Bibliography," Crossroads 12 (2015): 151-155.

- Sophia (October 19, 2018). "Old tomb sheds light on Ming dynasty's voyages". Life of Guangzhou.

- Levathes 1994, p. 80.

- Church 2005, p. 5.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 102.

- Needham 1971, p. 480.

- Dreyer 2007.

- "Zheng He xia Xiyang de chuan” ["The Ships with which Zheng He Went to the Western Ocean"] 鄭和下西洋的船, Dongfang zazhi 東方雜誌 43 (15 January 1947) 1, pp. 47-51, reprinted in Zheng He yanjiu ziliao huibian 鄭和研究資料匯編 (1985), pp. 268-272.

- Church 2005, pp. 1–2.

- Agius 2008, p. 250.

- Ming 2011, p. 14.

- Sleeswyk 2004, p. 305, 307.

- Barker, Richard (1989). "The size of the 'treasure ships' and other Chinese vessels". Mariner's Mirror. 75 (3): 273–275.

- Needham 1971, p. 481.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 111.

- Church 2005, p. 3.

- Agius 2008, p. 223.

- Agius 2008, p. 222.

- Church 2005, p. 23.

- Howarth, David (1981). The Voyage of the Armada: The Spanish Story. New York, NY: The Viking Press. Page 209–10; he asserts that the Spanish ships were “over-masted for Atlantic weather and had rigging which was too light”.

- Church 2005, p. 36.

- Howard 1979, pp. 229–232.

- Church 2005, p. 3, 37.

- Murray 2014, p. 173.

- Naiming 2016, p. 56-57.

- Xiaowei 2018, p. 111-112.

- Xiaowei 2018, p. 113.

- Xiaowei 2018, p. 110.

- Cunren 2008, p. 60.

- Zhengning 2015, p. 231.

- Sleeswyk 1996, p. 11-12.

- Longfei 2015, p. 377.

- Papelitzky 2019, p. 217-219.

- Miksic 2019, p. 1642.

- Papelitzky 2019, p. 212-213.

- Sernigi, Girolamo (1499). Translation in Ravenstein, E. G., ed. (1898). A Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama, 1497–1499. London: Hakluyt Society. p. 131. See also Finlay (1992), 225.

- Sally K., Church (2010). "Two Ming Dynasty Shipyards in Nanjing and their Infrastructure" (PDF). In Kimura, Jun (ed.). Shipwreck ASIA: Thematic Studies in East Asian Maritime Archaeology. Adelaide: Maritime Archaeology Program, Flinders University. pp. 32–49. ISBN 9780646548265.

- Wake 2004, pp. 65–66.

- Church 2005, p. 29.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 103-104.

- Church 2005, p. 30.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 152-153.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 162.

- "China To Revive Zheng He's Legend". China Daily. September 4, 2006. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.

- "East China to Rebuild Ship from Ancient Navigator Zheng He". Want China Times. October 24, 2010. Archived from the original on 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- 南京复建"郑和宝船" 2013年再下西洋 [Nanking is building a "Treasure ship" again; to sail again to the Western Ocean in 2013] (in Chinese), October 21, 2010

- Cang Wei; Song Wenwei (June 16, 2014). "Construction of ship replica put on hold". China Daily.

Sources

- Agius, Dionisius A. (2008), Classic Ships of Islam: From Mesopotamia to the Indian Ocean, Leiden: Brill

- Bowring, Philip (2019), Empire of the Winds: The Global Role of Asia's Great Archipelago, London, New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, ISBN 9781788314466

- Church, Sally K. (2005), "Zheng He: An Investigation into the Plausibility of 450-ft Treasure Ships" (PDF), Monumenta Serica Institute, 53: 1–43, doi:10.1179/mon.2005.53.1.001, S2CID 161434221

- Cunren, Chen (2008), 被误读的远行: 郑和下西洋与马哥孛罗来华考 (The Misunderstood Journey: Zheng He's Voyages to the West and Marco Polo's Visit to China), 广西师范大学出版社 (Guangxi Normal University Press), ISBN 9787563370764

- Dreyer, Edward L. (2007), Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405-1433, New York: Pearson Longman, ISBN 978-0-321-08443-9, OCLC 64592164

- Finlay, Robert (1992). "Portuguese and Chinese Maritime Imperialism: Camoes's Lusiads and Luo Maodeng's Voyage of the San Bao Eunuch". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 34 (2): 225–241. doi:10.1017/S0010417500017667. JSTOR 178944. S2CID 144362957.

- Jincheng, Guan (January 15, 1947), "鄭和下西洋的船 Zheng He xia Xiyang de chuan (The Ships with which Zheng He Went to the Western Ocean)", 東方雜誌 (Dong Fang Za Zhi), 43: 47–51

- Howard, Frank (1979), Sailing ships of war, 1400-1860, Conway Maritime Press

- Levathes, Louise (1994), When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne 1405-1433, Simon & Schuster

- Lewis, Archibald (December 1973), "Maritime Skills in the Indian Ocean 1368-1500", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 16 (2/3): 238–264, doi:10.2307/3596216, JSTOR 3596216

- Lo, Jung-pang (2012) [1957], Elleman, Bruce A. (ed.), China as Sea Power 1127-1368: A Preliminary Survey of the Maritime Expansion and Naval Exploits of the Chinese People During the Southern Song and Yuan Periods, Singapore: NUS Press

- Longfei, Xi (2015), 中国古代造船史 (History of Ancient Chinese Shipbuilding), Wuhan: Wuhan University Press

- Miksic, John M. (November 25, 2019), "The Bakau or Maranei shipwreck: a Chinese smuggling vessel and its context", Current Science, 117 (10): 1640–1646, doi:10.18520/cs/v117/i10/1640-1646

- Mills, J. V. G. (1970). Ying-yai Sheng-lan: 'The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores' [1433]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01032-2.

- Ming, Zheng (2011), "再议明代宝船尺度——洪保墓寿藏铭记五千料巨舶的思考 (Re-discussion on the Scale of Treasure Ships in the Ming Dynasty: Reflections on the Five Thousand Ships Remembered in the Life Collection of Hong Bao's Tomb)", 郑和研究 (Zheng He Research), 2: 13–15

- Murray, William Michael (2014), The Age of Titans: The Rise and Fall of the Great Hellenistic Navies, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199382255

- Naiming, Pang (2016), "船坚炮利:一个明代已有的欧洲印象 (Ship and Guns: An Existing European Impression of the Ming Dynasty)", 史学月刊 (History Monthly), 2: 51–65

- Needham, Joseph (1971), Science and Civilization in China Volume 4 Part 3, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

- Papelitzky, Elke (December 2019), "Weapons Used Aboard Ming Chinese Ships and Some Thoughts on the Armament of Zheng He's Fleet", China and Asia, 1 (2): 192–224, doi:10.1163/2589465X-00102004, S2CID 213253271

- Sen, Tansen (2016), The impact of Zheng He's expeditions on Indian Ocean interactions

- Sleeswyk, André Wegener (1996), "The Liao and the Displacement of Ships in the Ming Navy", Mariner's Mirror, 82 (1): 3–13, doi:10.1080/00253359.1996.10656579

- Sleeswyk, André Wegener (2004), "Notes on the overall dimensions of Cheng Ho's largest ships", Mariner's Mirror, 90: 305–308, doi:10.1080/00253359.2004.10656907, S2CID 220325919

- Suryadinata, Leo (2005), Admiral Zheng He and Southeast Asia, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies

- Wake, Christopher (December 1997), "The Great Ocean-Going Ships of Southern China in the Age of Chinese Maritime Voyaging to India, Twelfth to Fifteenth Centuries", International Journal of Maritime History, 9 (2): 51–81, doi:10.1177/084387149700900205, S2CID 130906334

- Wake, Christopher (June 2004), "The Myth of Zheng He's Great Treasure Ships", International Journal of Maritime History, 16: 59–76, doi:10.1177/084387140401600105, S2CID 162302303

- Xiaowei, Hu (2018), "郑和宝船尺度新考——从泉州东西塔的尺度谈起 (A New Research on the Scale of Zheng He's Treasure Ship——From the Scale of Quanzhou East-West Pagoda)", 海交史研究 (Journal of Maritime History Studies) (2): 107–116

- Zhengning, Hu (2015), "郑和下西洋研究二题—基于洪保《寿藏铭》的考察 (Two topics on Zheng He's voyages to the West—Based on the investigation of Hong Bao's "Shou Zang Inscription")", 江苏社会科 (Jiangsu Social Sciences), 5: 231–235

Further reading

- Traditions and Encounters - A Global Perspective on the Past by Bentley and Ziegler.