Jingtai Emperor

The Jingtai Emperor (21 September 1428 – 14 March 1457),[1] also known by his temple name as the Emperor Daizong of Ming (Chinese: 明代宗) and by his posthumous name as the Emperor Jing of Ming (Chinese: 明景帝), personal name Zhu Qiyu (朱祁鈺), was the seventh emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1449 to 1457. He succeeded his elder brother, Emperor Yingzong, who had been captured by the Mongols. After ascending the throne, he announced that the Chinese New Year of 1450 would be the beginning of the era of "Exalted View", Jingtai. He was overthrown in a palace coup led by Yingzong in February 1457, and died a month later.

| Jingtai Emperor 景泰帝 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

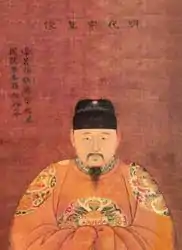

Posthumous illustration of the Jingtai Emperor, Qing dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Ming dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 22 September 1449 – 24 February 1457[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||||||||||

| Enthronement | 22 September 1449 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Emperor Yingzong (Zhengtong Emperor, first reign) | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Emperor Yingzong (Tianshun Emperor, second reign) | ||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Emeritus | Emperor Yingzong (1449–1457) | ||||||||||||||||

| Prince of Cheng | |||||||||||||||||

| First tenure | 8 March 1435 – 22 September 1449 | ||||||||||||||||

| Second tenure | 24 February – 14 March 1457 | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | 21 September 1428 Xuande 3, 13th day of the 8th month (宣德三年八月十三日) | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 14 March 1457 (aged 28) Tianshun 1, 19th day of the 2nd month (天順元年二月十九日) | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Jingtai Mausoleum, Beijing | ||||||||||||||||

| Consorts | |||||||||||||||||

| Issue |

| ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | Zhu | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Ming | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Xuande Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Dowager Xiaoyi | ||||||||||||||||

| Jingtai Emperor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 景泰帝 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

In 1449, Emperor Yingzong, at the suggestion of the eunuch Wang Zhen, personally led the army in marching against the Mongolian army of Esen Taishi. In the Battle of Tumu Fortress, the Ming army was crushed and the emperor was captured. Both the government and the country were shocked, and the court eventually responded by elevating the emperor's brother, Zhu Qiyu, who was charged with managing government affairs for the duration of the campaign, to the throne. The now-former emperor had meanwhile established good relations with Essen and was released in 1450, but did not return to power; he was kept under house arrest in the Southern Palace of the Forbidden City.

The Jingtai Emperor, supported by the prominent minister Yu Qian, restored the country's infrastructure; the Grand Canal and the Yellow River's dam system were repaired, leading to an economic prosperity and a strengthening of the country.

The emperor ruled for eight years before he fell ill, and in early 1457 his death became imminent. He had refused to designate an heir, as his son and crown prince had died in the fourth year of his reign under unclear circumstances, probably poisoned. Taking advantage of this opportunity, Emperor Yingzong seized the government in February 1457 through a palace coup. The Jingtai Emperor died a month later.

He was one of two Ming emperors who was not buried in either the Ming tombs in Beijing or the Xiaoling Mausoleum in Nanjing.

Early life and career as Prince of Cheng

The Jingtai Emperor was born on 11 September 1428;[2] his personal name was Zhu Qiyu, and Jingtai was the name of his reign era. Zhu Qiyu was the second son of the Xuande Emperor, the emperor of the Ming dynasty from 1425 to 1435. In 1435, the Xuande Emperor died, after which his eldest son, Emperor Yingzong, ascended the Ming throne and created Zhu Qiyu as Prince of Cheng (郕王).[2]

As the Prince of Cheng, Zhu Qiyu was said to have resided in Shandong (present-day Wenshang County, Jining) as an adult.[3] He was shy, weak, and indecisive by nature and had no interest in power.[2] He had a friendly relationship with his brother, which may have been why he stayed in the capital, even though he was old enough to move to Wenshang in the latter half of the 1440s.[3]

Ascension to the throne

In the summer of 1449, unrest was spreading along the northern border of the Ming dynasty. At the end of July, news reached Beijing that the Mongols, led by their de facto ruler Esen, had attacked Datong as part of a large-scale invasion.[4] Emperor Yingzong decided to lead the campaign against the Mongols personally, accompanied by his confidant Wang Zhen and many generals and officials.

On 3 August, Zhu Qiyu was entrusted with the provisional administration of Beijing, and he was assigned aides representing the most important power groups: the imperial family was represented by Prince Consort Commander Jiao Jing (焦敬), the Hongxi Emperor's son-in-law; the palace eunuchs were led by Jin Ying (金英) (head of the Directorate of Ceremonial and, in Wang Zhen's absence, the highest-ranking eunuch); the government was led by the Minister of Personnel, Wang Zhi (王直); and the fourth was grand secretary Gao Gu (高穀). All major decisions were to be deferred until the emperor's return.[3]

Emperor Yingzong went into battle on 4 August. The results of the month-long campaign were zero, but on the way back, the imperial army was surprised by the Mongols on 1 September, who dispersed them in the battle at the Tumu Fortress. Many senior commanders perished, and Emperor Yingzong was captured.

With the approval of Emperor Yingzong's mother, Empress Dowager Sun, Zhu Qiyu became the head of the government on 4 September. The empress dowager limited his influence by marking his authority as temporary, and on 6 September, she promoted the two-year-old Zhu Jianshen, Yingzong's eldest son, to the heir to the throne.[5]

On 15 September, high-ranking civil and military officials led by Yu Qian petitioned the Empress dowager to install Zhu Qiyu on the imperial throne. The purpose of this measure was to stabilize the government and improve the position of the Ming authorities in relations with the Mongols by reducing the importance of the captured Emperor Yingzong. As the only adult close relative of the captured emperor, Zhu Qiyu was a natural candidate.[2] Zhu Qiyu was startled by the proposal and rejected it; however, those around him saw his behavior as purely formal reluctance,[2] as is usual in similar cases. He eventually relented and ascended the throne as the Jingtai Emperor on 17 (22,[6] or 23[7]) September. He proclaimed the brother "emperor emeritus" (太上皇), which was formally a higher but only an honorary title.[8] Only one dignitary protested against the new emperor's accession, and he paid for it with his life.[7]

The Mongols did not attack Beijing immediately after their victory at Tumu, when they likely would have succeeded, but instead hesitated and gave the Ming two months to recover from the defeat. In the meantime, the Defense of Beijing was put in order by the new Minister of War, Yu Qian, who effectively became the head of the government even before the appointment of the new emperor. The Mongols did not approach the city until 27 October, but gave up the siege after four days when they realized they had no chance of success.[6]

The Jingtai Emperor's government rejected all of Esen's offers to ransom the captured emperor and demanded his unconditional return. The captive emperor became more of a nuisance to the Mongols, so they eventually returned him unconditionally. The Jingtai Emperor did not have the confidence to keep his brother free, so he interned him in the Southern Palace and isolated him from any connection with government officials. Fear of his brother overshadowed the rest of his reign and motivated a cautious policy towards the Mongols.[9]

Government

Ministers, eunuchs, secretaries

Traditional historians extol and praise the Jingtai Emperor's rule, especially in comparison to the bad and incompetent eunuchs who had dominated the previous decade. However, power did not simply shift from eunuchs to officials; even under the Jingtai Emperor, eunuchs held a significant amount of power. Rather, after 1449, both eunuchs and officials worked together to revive the country.[10]

To some extent, the Jingtai Emperor's regime followed the tradition of the rule of the "Three Yangs" (who ruled the empire from the mid-1420s to the early 1440s), with continuity with their regime embodied by Wang Zhi, who held the position of Minister of Personnel from 1443 to 1457. In the 1440s, he was a constant opponent of Wang Zhen, and after 1449, he cooperated with Yu Qian. From 1451 to 1453, he was assisted in office by the co-minister He Wenyuan (何文淵), who was replaced in 1453 by Wang Ao, whose rise was supported by Yu Qian. Wang Ao successfully defended Liaodong, later Guangdong and Guangxi; he remained Minister of Personnel until he died in 1467 at the age of 73. Widely respected Ministers of Personnel and their careful selection of capable officials produced a general quality of administration in the third quarter of the fifteenth century.[10]

The Jingtai Emperor's ministers usually remained in office for many years. The ministers of Revenue, Jin Lian (金濂); of Rites, Hu Ying (胡濙); of Justice, Yu Shiyue (俞士悅); and of Works, Shi Pu (石璞), were in office throughout his reign. The leadership of the Censorate (in the years 1445–1454, Chen Yi (陳鎰), then Yang Shan (楊善), Wang Wen (王文), Xiao Weizhen (蕭維禎), and Li Shi (李實)) and army commanders (Shi Heng (石亨), eunuchs Cao Jixiang (曹吉祥) and Liu Yongcheng (劉永誠)) were also constant.[10]

Among the Jingtai Emperor's important followers were the eunuchs Jin Ying and Xing An (興安). Jin Ying was very influential in the 1430s, but later lost power to Wang Zhen. Under the Jingtai Emperor, he became head of the Directorate of Ceremonial, but was imprisoned in 1450 for supporting the return of Emperor Yingzong. Xing An then took over as head of the eunuchs and played an important role in the negotiations for the return of Emperor Yingzong and in the exchange of the crown prince in 1452. The two mentioned eunuch generals, Cao Jixiang and Liu Yongcheng, played a major role in the military reform of 1453. On the other hand, the grand secretaries, Chen Xun (陳循) and Gao Gu, did not support the Jingtai Emperor among prominent officials.[11]

Despite personnel stability, the ruling group was not without controversy. In 1451–1452, Yu Qian, the most influential person in Beijing, came into sharp conflict with Shi Heng due to the abuse of power and corruption by Shi Heng and his family. The emperor was unable to calm the dispute until Yu Qian fell ill in 1454–55, resulting in a loss of much of his influence.[11]

Military reform

In 1451, after the immediate danger had passed, Yu Qian began military reform. He selected 100,000 soldiers from the remaining troops in the Beijing area, which he divided into five training divisions (團營, tuanying); in 1452, he added an additional 50,000 soldiers to them and created ten training units.[12] He also reorganized the command system of the capital garrison. Originally, command was divided between generals and eunuchs, and each of the three army camps (for infantry, cavalry, and firearms) was completely independent under its own field commander. However, detachments from different camps were not used to working together. Yu Qian subordinated each camp to one field commander and the entire garrison to the field marshal. At the same time, he took away the supervision of the garrison from the eunuchs, resulting in the creation of a unified command and a greater role for the capital generals in the management of the training camps.[12] The new arrangement of the drill camps was unique among the various Ming command systems, in that the generals directing the training commanded the same soldiers in battle.[13]

Due to the lack of men and the ineffectiveness of most of the hereditary soldiers, after 1449, the previously isolated practice of hiring soldiers for wages from among the peasant and urban population spread. Hired soldiers were called bing (兵), in contrast to hereditary soldiers, jun (軍).[14]

After Emperor Yingzong's return to power in 1457, Yu Qian was executed and his reforms reversed.[15]

Economy

Shandong suffered a famine in 1450, and in 1452–1454 the provinces of northern China and the lower reaches of the Yangtze River suffered heavily from rains and cold weather.[16] In northern China, the drought of 1455 was followed by the rains of the summer of 1456. Aid to the population and tax arrears depleted the state treasury.[17]

In 1453, the ban on using coins in trade was lifted. From the mid-1450s, illegal private coins from Jiangnan began to crowd out the old Yongle coins from Beijing markets. Occasional proposals to combat private coinage by resuming state production were rejected, so unofficial networks of illegal mints flourished.[18]

The government paid attention to the regulation of the Yellow River urgently after the great floods and changes in its course in 1448.[12] After this, the river flowed into the sea both north and south of the Shandong Peninsula. Furthermore, changes in the flow of the Yellow River caused issues with the supply of water to the Grand Canal. Attempts to rectify the situation and repairs from 1449 to 1452 were unsuccessful. In 1453, Xu Youzhen (徐有貞), who had fallen out of favor during the crisis of 1449 when he proposed moving the capital from Beijing to Nanjing, presented a plan to rebuild the levees and canals. Within two years, with a force of up to 58,000 workers, he carried out complex repairs to dams and excavated hundreds of kilometers of canals. His work successfully withstood the great flood of 1456 and served for decades.[19]

Traditional history perceives the 1450s primarily in the light of the rivalry between the two imperial brothers; however, Marxists primarily recall class conflicts.[20] There was persistent discontent among the population, which fueled rebellions and kept the army busy for most of the 1450s. By 1452, the uprisings in Fujian and Zhejiang had died down.[16] In the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi, the non-Han Chinese population (Miao and Yao tribes) grew arbitrarily until they were forcefully suppressed by Wang Ao in 1452–1453.[21] In 1450–52, the Miao and Yao revolted in Guizhou and Huguang. In the years 1453–56, unrest continued in Fujian, Huguang, Sichuan, and Zhejiang.[16] Throughout the 1450s, armed clashes lasted in Guangdong, where the authorities mobilized loyal tribes against the rebels.[21] Non-Han Chinese peoples generally rebelled against the Ming government, while Han Chinese miners and landless people in the peripheral areas of the provinces generally kept calm.[16]

Overall, the Jingtai Emperot's reign was a time of successful reforms and restoration of stability achieved by capable ministers.[22] In the field of culture, the Jingtai era was particularly notable for the development of wire enamel (cloisonné) decoration,[23] which has since been referred to as Jingtai-lan (景泰藍; literally "blue [color of the era] Jingtai") in Chinese.

Succession problems, deposition and death

A persistent political problem during Jingtai's rule was the fate of Emperor Yingzong and the question of succession. Although Emperor Yingzong was isolated, he still had supporters in the government, such as the Minister of Rites Hu Ying.[17] Normally, the emperor's opponents would have had to leave office, but the emperor hesitated to resolve the aforementioned problems and kept them in the government.[9]

The crown prince was the eldest son of Emperor Yingzong from 1449. However, the emperor decided after some time to keep the throne for his offspring. He gradually gained sufficient support for his plan, partly through bribery and partly through intimidation,[9] and on 20 May 1452, despite the continued opposition of the grand secretaries and some other officials,[17] he appointed the current successor as the Prince of Yi and his son Zhu Jianji as the crown prince.[9] On the same day, Empress Wang was deposed and replaced by the heir's mother, Lady Hang. This apparent defense of personal interests weakened the emperor's prestige.[24]

Zhu Jianji died in 1453 and his mother in 1456. The emperor had no other son and a new crown prince was not named.[9][24] Some, such as the Director of the Ministry of Rites Zhang Lun (章綸; d. 1483) and the censor Zhong Tong (鍾同; d. 1455) suggested the reinstatement of Emperor Yingzong's eldest son, for which they were imprisoned. Zhong Tong and some others were flogged to death.[9] After that, ambitious men at court and in government began to organize conspiracies in Emperor Yingzong's favor.[24]

The conspiracy was led by Shi Heng, Cao Jixiang, Xu Youzhen, and Zhang Fu (張軏; 1393–1458). An opportunity was found when the emperor fell ill at the end of 1456, so he did not grant audiences for several days and cancelled the ceremonies of the New Year in 1457. The request for the appointment of a successor remained unanswered, and the court prepared in an atmosphere of anxiety for the emperor's death.[9] On the morning of 11 February 1457, the conspirators dragged Emperor Yingzong out of his residence and placed him on the throne, to the surprise of officials who had come for the morning audience. Yingzong immediately made changes in the government, promoting the conspirators and dismissing the officials of the previous government. Some of the supporters of the Jingtai regime were killed, such as Yu Qian, Wang Wen, and three high-ranking eunuchs.[9]

The Jingtai Emperor was demoted to the Prince of Cheng. He did not recover from his illness and died on 14 March 1457.[23] It is speculated that he may have been murdered.[lower-alpha 4] He was given the posthumous name Li (戾, "Rebel") and was buried outside the grounds of the imperial mausoleums, at Yuchuanshan. Some officials also suggested abolishing his era name, just as the Jianwen era had been abolished, but Emperor Yingzong did not agree. It was not until 1475, during the reign of the Chenghua Emperor, that the Jingtai Emperor was given a posthumous name—Emperor Gongren Kangding Jing (恭仁康定景皇帝)—shorter than that of other emperors. He received the temple name Daizong (代宗) in the middle of the 17th century from a ruler of the Southern Ming dynasty in Nanjing.[23]

Family

Consorts and Issue:

- Empress Xiaoyuanjing, of the Wang clan (孝淵景皇后 汪氏; 1427–1507)

- Princess Gu'an (固安郡主; 1449–1491), first daughter

- Married Wang Xian (王憲) in 1469, and had issue (one son)

- Second daughter

- Princess Gu'an (固安郡主; 1449–1491), first daughter

- Empress Suxiao, of the Hang clan (肅孝皇后 杭氏; d. 1456)

- Zhu Jianji, Crown Prince Huaixian (懷獻皇太子 朱見濟; 28 March 1445 – 21 March 1453), first son

- Imperial Noble Consort, of the Tang clan (皇貴妃 唐氏; 1438–1457)

- Li Xi'er (李惜儿)

- Consort, of the Sun clan (妃 孫氏)

Ancestry

| Hongwu Emperor (1328–1398) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Yongle Emperor (1360–1424) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaocigao (1332–1382) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hongxi Emperor (1378–1425) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Xu Da (1332–1385) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Renxiaowen (1362–1407) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Xie | |||||||||||||||||||

| Xuande Emperor (1399–1435) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zhang Congyi | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zhang Qi | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Zhu | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Chengxiaozhao (1379–1442) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tong Shan | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Tong | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jingtai Emperor (1428–1457) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Yanming | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Dowager Xiaoyi (1397–1462) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Shen | |||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- On 11 February 1457 (seventeenth day of first month in the eighth year of Jingtai era), Emperor Yingzong of Ming restored his imperial crown and rule (274th volume of Yingzong Shilu in Ming Shilu). On 24 February 1457 (first day of second month in the first year of Tianshun era), Empress Xiaogongzhang deposed Jingtai Emperor (275th volume of Yingzong Shilu in Ming Shilu).

- Demoted to the princely rank by his elder brother, the restored Emperor Yingzong of Ming, he received the posthumous name Li (戾 – "the Rebellious", "the Violent") when he died in 1457; however, his nephew Chenghua Emperor restored his imperial title in 1476 and changed his posthumous name to Emperor Gongren Kangding Jing.

- Was denied a temple name by his elder brother, the restored Emperor Yingzong of Ming, but in 1644 Zhu Yousong, the Hongguang Emperor of the Southern Ming, conferred on him the temple name Daizong, which is accepted in most history books, unlike the temple name of the Jianwen Emperor, also conferred by the Prince of Fu, but not recorded in most history books. "Dai" (代) means "proxy", in reference to the Jingtai Emperor being a regent emperor only, as his brother had been taken prisoner by the Mongols.

- The first to claim murder was Lu Yi (陸釴; 1439–1489), a Hanlin academic who also taught at the palace school for selected eunuchs. According to his private notes, the Jingtai Emperor was strangled by the eunuch Jiang An (蔣安).[23]

References

- "Jingtai | emperor of Ming dynasty". Britannica. 2008.

- Goodrich, L. Carington; Fang, Chaoying (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644. Columbia University Press. p. 294.

- Heer, Ph. de (1986). The Care-taker Emperor : Aspects of the Imperial Institution in Fifteenth-century China as Reflected in the Political History of the Reign of Chu Chʾi-yü. Leiden: Brill. p. 17.

- Heer, p. 16.

- Heer, p. 21.

- Goodrich, p. 295.

- Twitchett, Denis C; Grimm, Tilemann (1988). "The Cheng-t'ung, Ching-t'ai, and T'ien-shun reigns, 1436—1464". In Twitchett, Frederick W.; Mote, Denis C (eds.). The Cambridge History of China Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 327. ISBN 0521243327.

- Goodrich, p. 291.

- Goodrich, p. 296.

- Twitchett, Grimm, p.332.

- Twitchett, Grimm, p.333.

- Twitchett, Grimm, p.334.

- Hucker, Charles O (1988). "Ming government". In Twitchett, Frederick W.; Mote, Denis C (eds.). The Cambridge History of China 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1368 — 1644, Part II. Cambridge University Press. p. 103. ISBN 0521243335.

- Hucker, p. 68.

- Goodrich, p. 295–296.

- Twitchett, Grimm, p.336.

- Twitchett, Grimm, p.337.

- Von Glahn, Richard (1996). Fountain of Fortune: money and monetary policy in China, 1000–1700. University of California Press. p. 84.

- Twitchett, Grimm, p.335.

- Twitchett, Grimm, p.335–336.

- Faure, David (2006). "The Yao Wars in the Mid-Ming and their Impact on Yao Ethnicity". In Crossley, Pamela Kyle; Siu, Helen F.; Sutton, Donald S (eds.). Empire at the Margins : Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern China. University of California Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-520-23015-9.

- Twitchett, Grimm, p.331.

- Goodrich, p. 297.

- Twitchett, Grimm, p.338.