M. Stanley Livingston

Milton Stanley Livingston (May 25, 1905 – August 25, 1986) was an American accelerator physicist, co-inventor of the cyclotron with Ernest Lawrence, and co-discoverer with Ernest Courant and Hartland Snyder of the strong focusing principle, which allowed development of modern large-scale particle accelerators. He built cyclotrons at the University of California, Cornell University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. During World War II, he served in the operations research group at the Office of Naval Research.

Milton Stanley Livingston | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 25, 1905 |

| Died | August 25, 1986 (aged 81) |

| Alma mater | Pomona College Dartmouth College University of California, Berkeley |

| Known for | development of the cyclotron and strong focusing |

| Spouse(s) | Lois Robinson, Margaret Hughes |

| Awards | Enrico Fermi Award (1986) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics (accelerator physics) |

| Institutions | UC Berkeley, Cornell University, MIT, Brookhaven National Laboratory |

| Thesis | The Production of High Velocity Hydrogen Ions without the Use of High Voltages (1931) |

| Doctoral advisor | Ernest Lawrence |

| Signature | |

Livingston was the chairman of the Accelerator Project at Brookhaven National Laboratory, director of the Cambridge Electron Accelerator, a member of the National Academy of Sciences, a professor of physics at MIT, and a recipient of the Enrico Fermi Award from the United States Department of Energy. He was associate director of the National Accelerator Laboratory from 1967 to 1970.

Early life

Livingston was born in Brodhead, Wisconsin, on May 25, 1905, the son of McWhorter Livingston, a minister of religion, and his wife Sarah Jane.[1] Sarah was a member of the Ten Eyck family, an influential New York family whose Dutch origins date back to the 1640s. He had three sisters. The family moved to California when Livingston was five years old, and he grew up in Burbank, Pomona and San Dimas. His father became a high school teacher and principal. His mother died when he was 12 years old, and his father later remarried. Livingston thereby acquired five half-brothers.[2]

After graduating from high school in 1921, Livingston entered nearby Pomona College, intending to major in chemistry,[1] but he disliked the way that chemistry was being taught there, and arranged with the professor of physics, Roland R. Tileston, to take physics courses as well.[2] He received his Bachelor of Arts (AB) in 1926,[3] with a double major in physics and chemistry. Tileston arranged for him to then enter Dartmouth College with a teaching fellowship.[2] He was awarded his Master of Arts (MA) in 1928,[3] studying x-ray diffraction,[4][5] and stayed on for another year as an instructor.[2]

Cyclotrons

During that year, Livingston applied to graduate schools for teaching fellowships, and was accepted by both Harvard University and the University of California. He accepted the latter and returned to California.[2] He wrote his Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis on "The Production of High Velocity Hydrogen Ions without the Use of High Voltages",[6] a topic suggested by Ernest Lawrence, who had noticed that ions of mass and charge moving in a uniform magnetic field circulate at a constant frequency independent of energy:

In theory, therefore, if a particle traversed an electrode with a voltage V N times, it would acquire energy of NeV. Stanley's task was to verify if this would work. In January 1931, Stanley managed to do just that, using a voltage of 1 kV to accelerate hydrogen ions to 80 keV. At Lawrence's prompting, Stanley quickly wrote up his thesis and submitted it in April 1931 so that he would be eligible for an instructorship the following year.[1] His oral exam proved more difficult. Raymond Birge started asking questions about nuclear physics, and Livingston had to admit that he knew nothing about the work of Ernest Rutherford, James Chadwick, and Charles Drummond Ellis, and had not read their 1930 monograph Radiations from Radioactive Substances. Nonetheless, Lawrence managed to persuade the examiners to award Livingston his doctorate.[2]

In what would become a recurring pattern, as soon as there was the first sign of success, Lawrence started planning a new, bigger machine, which became known as a cyclotron. Lawrence and Livingston drew up a design for an $800 27-inch (69 cm) cyclotron in early 1932, with a magnet that weighed 2 tons. Lawrence then found a massive 80-ton magnet that had originally been built to power a transatlantic radio link during World War I, but was now rusting in a junkyard in Palo Alto. This allowed them to build a 27-inch cyclotron.[7][8]

In the cyclotron, they had a powerful scientific instrument, but this did not translate into scientific discovery. In April 1932, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton at the Cavendish laboratory in England announced that they had bombarded lithium with protons and succeeded in transmuting it into helium. The energy required turned out to be quite low—well within the capability of the 11-inch cyclotron. On learning about it, Lawrence wired the Berkeley and asked for Cockcroft and Walton's results to be verified. It took the team until September to do so, mainly due to lack of adequate detection apparatus.[9]

Between 1932 and 1934, Livingston authored or co-authored over a dozen papers on nuclear physics and the cyclotron, but he felt overshadowed by Lawrence, and did not think that he had gotten sufficient credit for his part in designing the cyclotron, for which Lawrence would receive the Nobel Prize in Physics in November 1939.[1][10] Livingston therefore accepted an offer of an assistant professorship from Cornell University in 1934.[3] He built a 2 MeV cyclotron at Cornell with an $800 grant and the help of graduate students and the departmental shop, the first one to be built outside Berkeley.[1] He worked with Robert Bacher and Hans Bethe, helping produce one of the three milestone papers that appeared in Reviews of Modern Physics that became known as the "Bethe Bible".[4][11] He also teamed up with Bethe to demonstrate for the first time that the neutron has a magnetic moment.[1][12] Livingston recalled that Bethe:

… gave me a feeling for the fundamentals of physics, and of what was going on in nuclear physics. With him for the first time I sensed how deep the field was, how involved it was, and how much we needed in the way of new information. I learned of many new kinds of concepts like magnetic moments and quantum aspects, that I had never heard of while with Lawrence. It was a different environment. I was now following a scholar and was really impressed.[2]

Physicists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) had decided that they too needed a cyclotron, and Robley Evans hired Livingston to build a 42-inch (110 cm) cyclotron there in 1938. Livingston became an instructor at MIT the following year, and an assistant professor the year after. The cyclotron was completed in 1940. During World War II, he worked with the cyclotron for the Office of Medical Research of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), producing radioactive isotopes of phosphorus and iron that were used as tracers in medical experiments. The result of this research was new methods of stabilizing blood, so that it could be shipped to the troops in remote theaters of war.[2] In 1944, Livingston joined Philip Morse's operations research group at the Office of Naval Research, and he worked in Washington, D.C., and London on radar countermeasures to the U-boats.[4]

Later life

Livingston returned to MIT soon after the end of the war, but in 1946 a consortium of universities including MIT banded together to create the Brookhaven National Laboratory in Long Island, New York, as a facility for carrying out Big Science research activities that were beyond the resources of a single academic institution. Morse was appointed as Brookhaven's first director, and he asked Livingston to take charge of building an accelerator for the new national laboratory. It was decided that it should be a new type of accelerator known as synchrotron that had been proposed by Edwin McMillan in 1945. Isidor Isaac Rabi in particular argued that it should be more powerful than any planned by the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory.[1][4]

As it turned out, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was unwilling to fund two giant 10 GeV accelerators, but was willing to fund two smaller ones of 2.5 GeV and 6 GeV. At a meeting at which Brookhaven was represented by Morse, Livingston and Leland John Haworth, the Brookhaven team accepted the smaller one, hoping that they would be able to get it finished first and thereby have an advantage in building the 10 GeV machine.[1][2] The machine, known as the Cosmotron, was approved by the AEC in April 1948, and reached its full power of 3.3 GeV in 1953.[13]

Livingston was unable to stay at Brookhaven to see the Cosmotron project completed because he faced losing his tenure at MIT, and elected to return there in 1948.[2] At MIT he taught classes, and participated in a 1950 experiment by the Los Alamos National Laboratory to investigate the lifetimes of short-lived fission products.[1] He still thought about accelerators, though, and in 1952, along with Ernest Courant, Hartland Snyder and J. Blewett at Brookhaven, developed strong focusing, the principle that the net effect on a particle beam of charged particles passing through alternating field gradients is to make the beam converge.[4][14] The advantages of strong focusing were then quickly realised, and deployed on the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron, which achieved 33 GeV in 1960.[13] A plan to build a synchrotron at MIT and Harvard also came to fruition under Livingston's leadership, resulting in the Cambridge Electron Accelerator (CEA), which became operational in 1962.[1] The hydrogen bubble chamber at the CEA exploded on July 6, 1965, injuring eight people, one of them fatally.[15]

The National Accelerator Laboratory, was renamed the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in 1974, was established in Batavia, Illinois, in 1967.[16] Like Brookhaven, it was run by a consortium of universities.[17] Robert R. Wilson was appointed its first director, with Livingston as his associate director[1] They initiated the design of what became the Tevatron, a 1 TeV particle accelerator.[1]

Livingston retired in 1970, and moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico. He continued to occasionally work as a consultant at the nearby Los Alamos National Laboratory, and sometimes acted as an administrative judge for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.[1] He married Lois Robinson while he was a graduate student at Berkeley in 1930. They had two children, a daughter, Diane, and a son, Stephen. They were divorced in 1949, and he married Margaret (Peggy) Hughes in 1952. After Peggy died he remarried Lois in 1959. He died in Santa Fe on August 25, 1986, from complications arising from prostate cancer.[1] He was survived by his wife Lois and children Diane and Stephen.[17]

Awards and distinctions

- Honorary degrees from Dartmouth College (1963), Hamburg, Germany (1967), and Pomona College (1971).[1]

- Elected to the National Academy of Sciences (1970)[18]

- Enrico Fermi Award from United States Department of Energy (1986) (posthumous)[19]

Notes

- Courant, E. D. (1997). "Milton Stanley Livingston". Biographical Memoirs. National Academies Press. 72. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- "Oral History Transcript — Dr. M. Stanley Livingston". American Institute of Physics. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- "M. Stanley Livingston". Array of Contemporary Physicists. Archived from the original on 2 August 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- Courant, E. D.; Livingston, M. S.; Snyder, H. S. (1952). "The Strong-Focusing Synchrotron—A New High Energy Accelerator". Physical Review. 88 (5): 1190–1196. Bibcode:1952PhRv...88.1190C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.88.1190. hdl:2027/mdp.39015086454124.

- Blewett, John P.; Courant, Ernest D. (June 1987). "Obituary: M. Stanley Livingston". Physics Today. 40 (7): 88–92. Bibcode:1987PhT....40f..88B. doi:10.1063/1.2820097.

- "The Production of High Velocity Hydrogen Ions without the Use of High Voltages". Inspire, the High Energy Physics information system. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- Herken 2002, pp. 5–7.

- "The Rad Lab – Ernest Lawrence and the Cyclotron". American Institute of Physics. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- Heilbron & Seidel 1989, pp. 137–141.

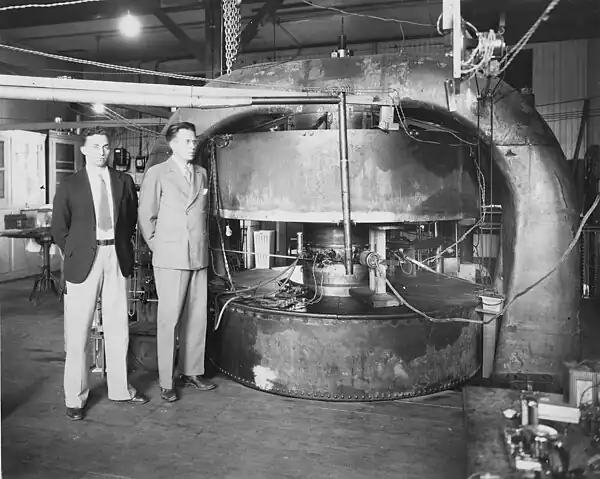

- "Ernest Lawrence and M. Stanley Livingston". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- Livingston, M. Stanley; Bethe, H. A. (July 1937). "Nuclear Physics C. Nuclear Dynamics, Experimental". Reviews of Modern Physics. American Physical Society. 9 (3): 245–390. Bibcode:1937RvMP....9..245L. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.9.245.

- Hoffman, J. G.; Livingston, M. Stanley; Bethe, H. A. (February 1937). "Some Direct Evidence on the Magnetic Moment of the Neutron". Physical Review. 51 (3): 214–215. Bibcode:1937PhRv...51..214H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.51.214.

- "A History of Leadership in Particle Accelerator Design". Brookhaven National Laboratory. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- Blewett, J. P. (1952). "Radial Focusing in the Linear Accelerator". Physical Review. 88 (5): 1197–1199. Bibcode:1952PhRv...88.1197B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.88.1197.

- "The CEA Blast: A Chronology". Harvard Crimson. 29 September 1965. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- "NAL Dedication". Fermilab. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- "M. Stanley Livingston; Atom-Smasher Builder". The New York Times. 20 September 1986. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- "Science academy adds 50 members; Election in Capital Honors Research Achievements". New York Times. 3 May 1970. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- "Courant and Livingston Win 1986 Fermi Awards" (PDF). Brookhaven Bulletin. 40 (47). 5 December 1986. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

References

- Herken, Gregg (2002). Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller. Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8050-6589-3.

- Heilbron, J. L.; Seidel, Robert W. (1989). Lawrence and his Laboratory: A History of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06426-3.