Milošević–Tuđman Karađorđevo meeting

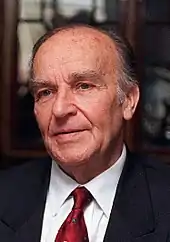

On 25 March 1991, the presidents of the Yugoslav federal states SR Croatia and SR Serbia, Franjo Tuđman and Slobodan Milošević, met at the Karađorđevo hunting ground in northwest Serbia. The publicized topic of their discussion was the ongoing Yugoslav crisis. Three days later all the presidents of the six Yugoslav republics met in Split. Although news of the meeting taking place was widely publicized in the Yugoslav media at the time, the meeting was overshadowed by the crisis in progress, that would lead to the breakup of Yugoslavia.

| ||

|---|---|---|

President of Serbia and Yugoslavia

Elections Family

.svg.png.webp) |

||

| ||

|---|---|---|

President of Croatia

Elections Family

|

||

In the following years, however, the meeting became substantially more controversial, as numerous Yugoslav politicians claimed that Tuđman and Milošević had discussed and agreed to the partitioning of Bosnia and Herzegovina along ethnic lines, such that territories with either a Croat or Serb majority would be annexed to the soon to be independent Croatia or Serbia respectively, with a rump Bosniak buffer state remaining in between.

Others have denied that any such agreement took place and since the Tuđman–Milošević talks took place with neither witnesses nor transcript, the exact content of the talks is not known. Historians have generally assessed it likely for the partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina to have been the topic of discussion at the meeting, but that beyond broad strokes, no clear agreement would have been reached at this meeting.

Background

At the start of 1991, ethnic tensions in Yugoslavia, especially between the two largest ethnic groups, the Serbs and Croats, were worsening. At that time, many meetings between the leaders of all six Yugoslav republics took place. The first one was on 6 January 1991.[1]

On 21 January, a meeting of delegations from SR BiH and SR Croatia, led by Alija Izetbegović and Franjo Tuđman, took place in Sarajevo. In the public report from the meeting, it was stated that both sides agreed that the crisis should be resolved peacefully and that outer and inner borders would be maintained.[2] After the meeting Izetbegović said that there was an "absolute agreement of the leaders of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia about the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina", and that there are some different views about Yugoslav People's Army (JNA).[3]

On 22 January, Izetbegović met with Slobodan Milošević in Belgrade. After the meeting, Alija Izetbegović said: "Today I am a bigger optimist than I was three days ago." He added that "he has an impression" that the Serbian side had some reservations about the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the event Yugoslavia broke up, but that it was not a problem if Yugoslavia survived.[4]

On 23 January, Tuđman met the President of the SR Montenegro Momir Bulatović. In the public report the differences in their views were clear: Tuđman claimed that "borders between republics are borders of sovereign states", while Bulatović claimed that they are "administrative borders" which would become an issue in the case of the establishment of a confederation (Yugoslavia was a federation).[5]

On 24 January, delegations from SR Slovenia and SR Serbia, led by Milan Kučan and Slobodan Milošević, met in Belgrade. Kučan and Milošević agreed that SR Slovenia could leave Yugoslavia and that Serbs have the right to live in the same country.[6] The agreement was formalised on 14 August 1991, after Slovenia seceded.[7]

On 25 January, a Croatian delegation, led by Tuđman, came to Belgrade. On the same day in Sarajevo, Izetbegović met Bulatović.

These meetings did not stop military tensions. On 25 January, the Federal Secretariat for National Defense (SSNO) directly accused Croatia of preparing paramilitary forces to attack the Yugoslav People's Army. The Army moved to its highest state of readiness. The SSNO accusations were perceived by some as a proclamation of war and a prelude to a military coup.[8] The military leadership did not achieve support from a majority in the Yugoslav presidency and there was no military intervention.[9]

On the extended meeting of the Presidency of Yugoslavia on 13 February, about giving Slovenia permission to leave, Tuđman said: "In that Yugoslavia, without Slovenia - there is no Croatia too. I think I was clear enough."[10]

On 23 February, Izetbegović said that there was essentially no more Yugoslavia, and that there will be a "triple level federation" instead: Slovenia and Croatia would be independent, Serbia and Montenegro would be in the core of the new state, and BiH and Macedonia would be in between, with BiH much closer to Serbia than to Croatia. Izetbegović was heavily attacked by public opinion, claiming that he had given BiH to Milošević.[11]

In early March, the Pakrac clash saw a confrontation between Croat police and rebel Serb forces. On 9 March, the Yugoslav Army rushed to defend Milošević's government during the March 1991 protests in Belgrade.[12]

From 12–16 March 1991, a joint meeting of the Presidency of SFRY, in its capacity as the high command of the armed forces, took place. At the meeting, the military leadership, led by Serbian officials, tried to introduce a state of emergency in the whole of Yugoslavia. Milošević stated that he no longer recognized the authority of the Presidency.[13][14]

In this situation, all six leaders of the Yugoslav republics, Franjo Tuđman, Slobodan Milošević, Alija Izetbegović, Kiro Gligorov (SR Macedonia), Milan Kučan and Momir Bulatović organized a meeting in Split for 28 March 1991. A meeting was held between Tuđman and Milošević on 25 March in Karađorđevo, in preparation for the meeting in Split, as the leaders of the two biggest republics decided to try to agree on suggestions for resolving the crisis.[15]

The meeting and public response

The meeting between Franjo Tuđman and Slobodan Milošević took place on the afternoon of 25 March 1991 in Karađorđevo near Bačka Palanka in the Serbian province of Vojvodina.[17][18] At the time, the meeting did not seem to be different from any other meeting of republican leaders. The report of the meeting was in the public news the same and the days following.[17] Foreign newspapers such as Le Monde, Le Figaro and Libération in France, also published short reports about the meeting, noting that "the two largest republics agreed to solve the difficult Yugoslav crisis in the next two months".[19] According to the reports, the leaders discussed resolving the Yugoslav crisis and preparing for the upcoming meeting in Split with the rest of the leaders of the Yugoslav republics.[20] As usual, in bilateral meetings, most of the discussion was held by Tuđman and Milošević alone, without other witnesses or a record kept. There was no official agreement of any kind.

Sarajevo newspaper Oslobođenje called the meeting "secret". From the beginning, there was speculation about what the two presidents discussed. The most common speculation was replacing the Prime minister of Yugoslavia Ante Marković.[21] The first to speculate that the focus of the talks was Bosnia and Herzegovina, was an Oslobođenje journalist Miroslav Janković of Sarajevo on 14 April:

It is not necessarily to be very smart (...) to conclude that in the middle of that talks and tables was: Bosnia. The land across which passes every calculation and map of any future Yugoslavia.[22]

Subsequent meetings

Tuđman and Milošević met on another occasion on 15 April in Tikveš in Baranja. The next day, all newspapers published the report of the meeting.[23] After the meeting, expert groups from Croatia and Serbia discussed solving the Yugoslav crisis. Testimonies of the meetings by group members do not fully agree; but they all agree that there were no results.[24][25][26][27]

On 12 June, in Split, Tuđman, Milošević and Izetbegović had a trilateral meeting. News of the meeting was public the next day, and no agreement was reached. Unlike the meeting in Karađorevo, this time immediate public speculation was that the trio had divided Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo newspaper Bosanski pogledi (Bosnian views) had a title the next day: "Tuđman, Milošević, Izetbegović, Tripartite Pact for the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina". Izetbegović denied such speculations and said that it was "not possible to talk with him about that".[21]

Aftermath

The most immediate significance of the meeting was not a deal over Bosnia and Herzegovina, but the absence of a deal over Croatia. Milošević made a speech one week after the Belgrade riots where he outlined plans which involved the incorporation of a large area of Croatia into the new Yugoslavia. In spite of the meetings, the Croatian War of Independence started on 31 March 1991 with the Plitvice Lakes incident, where a clash of Croat and Serb forces occurred.[18]

Franjo Tuđman and the Croatian government have denied, on numerous occasions, that there was an agreement at Karađorđevo. Tudman stated, in his October 1991 speech, that the Serbs controlled all of the Yugoslav Army and the Serb rebellion in Croatia, during the Croatian war of independence, was just the beginning.[28] Croatia declared independence on 8 October 1991. By the end of the year, nearly one-third of Croatia was occupied by Serbian forces. Most countries recognized the independent Croatia on 15 January 1992.

At a meeting with a Bosnian Croat delegation on December 27, 1991, Tuđman announced that conditions allowed for an agreement to redraw the boundaries of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as it was not yet independent, and peace plans at the time envision it as a "three nations" country.[29]

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the first fights started on 1 October 1991, when the Yugoslav People's Army, controlled by Serbs, attacked the Croat-populated village of Ravno in Herzegovina. Alija Izetbegović considered that as part of the war in Croatia, and ignored it, saying that "it is not our war".[30] On 3 March 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence. In the following days, many countries, including Croatia, recognized the independence of BiH. The Bosnian War soon began and would last until November 1995. Serbs attacked Muslims in Bijeljina on 1 April 1992, and soon after, the Bosnian War worsened.

The Graz agreement was a proposed truce between Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić and Bosnian Croat leader Mate Boban on April 27, 1992, signed in the town of Graz, Austria. At this point, Serb forces controlled 70 percent of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The treaty was meant to limit conflict between the Serb and the Croat forces.[31] Bosnian Muslims saw this as a sequel to the Croat-Serb deal about Bosnia. In between the newly expanded Croatia and Serbia would be a small Bosniak buffer state, pejoratively called "Alija's Pashaluk" by Croatian and Serbian leadership, and named after Bosnian president Alija Izetbegović.[32] The ICTY judgement in the Blaškić case suggests a reported agreement at the Graz meeting between Bosnian Serb and Bosnian Croat leaders. [33]

By the end of 1992, the Serbs controlled two thirds of the country. Although allies at the beginning, Croats and Muslims (Bosniaks) fought in Bosnia and Herzegovina from October 1992 until February 1994. After signing the Washington Agreement they ended the war again as allies. The internal structure of Bosnia and Herzegovina was discussed and was finally decided with the Dayton Agreement. Some internal divisions remained, most notably the Republika Srpska.

Claims of impact

At the time, the meeting in Karađorđevo did not appear different from previous meetings of the leaders of the Yugoslav republics. However, in future years, this meeting, and sometimes the later meeting of Tuđman and Milošević in Tikveš, became famous because of claims that the participants had discussed and agreed upon a partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Political scientist Kristen P. Williams noted in 2001 how the Bosnian leadership at the time viewed the meeting as part of a collusion between Milošević and Tuđman to destroy Bosnia.[34]

The majority of Bosnian historians and politicians consider the meeting to be the start of a Serbo-Croatian conspiracy against the Bosniaks, and consider the thesis of a partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina between Croatia and Serbia an irrefutable fact.[35] It was also widely cited, in Croatian public life, by politicians opposing Tuđman.[36]

The main participants of the meeting, Franjo Tuđman and Slobodan Milošević, denied that there was ever discussion, or an agreement, about the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina. A joint statement in Geneva in 1993, by President Milošević and President Tuđman, said: "All speculations about a partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina between Croatia and Serbia are entirely unfounded." But Milošević said of the partition: "It is a solution which is offering to the Muslims much more than they can ever dream to take by force."[37]

Tuđman later said that during the Karađorđevo meeting, he told Milošević that Croatia could not allow a Serbian Bosnia and Herzegovina because Dalmatia would be threatened. So he had suggested a confederation of three nations in BiH.[38] In a 1997 interview with Corriere della Sera, Tuđman repeated: "There has never been any agreement between me and Milošević, there was no division of Bosnia".[39]

In the 2000 judgement against Tihomir Blaškić, it was stated that aspirations for a partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina were displayed during the meeting in Karađorđevo "on 30 March 1991".[40] An inaccurate date was given in the judgement, as the meeting was held on 25 March 1991. The chamber relied on the testimony of Stjepan Mesić in its conclusion regarding Karađorđevo.[41]

In the 2002 ICTY indictment against Milošević, the prosecution stated that: "On 25 March 1991, Slobodan Milošević and Franjo Tuđman met in Karađorđevo and discussed the partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina between Serbia and Croatia."[42]

On the other hand, most Croatian historians consider it a political myth because of a lack of direct evidence, and the difficulty of explaining the Yugoslav Wars, with Croats and Serbs as the main antagonists, in the context of a Serbo-Croatian agreement.[43] Ivica Lučić and Miroslav Tuđman claim that testimonies do not match, and that the anomalies can be explained by particular political interests.[43][44]

Izetbegović and Gligorov

On 24 March 1991, a day before the meeting in Karađorđevo, Izetbegović sent a letter to Tuđman. In it, he wrote:

I am convinced (and also have some information) that he will, in bilateral talks, offer you some partial solutions, which would partly be implemented against Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina. I ask you not to accept those offers (...)[45]

In the summer of 1996, Izetbegović said that he found out about the meeting on 27 March from Macedonian president Gligorov, although the news of it was public the same day, 25 March. He said that Gligorov told him that he has "reliable information" that Tuđman and Milošević spoke about the "partition of BiH". He said that they did not know more details, but concludes:

However, it is today clear that what happened in Karađorđevo makes the whole history of our relations and explains events which followed all this, three to four years afterwards.[46]

Kiro Gligorov said on Radio Free Europe, in 2008, that everything he knew about the meeting, Tuđman had told him in September 1991.[47]

Alleged recordings

In November 1992, Dobroslav Paraga, leader of the right-wing Croatian party HSP, publicly announced that he has recordings of talks between Tuđman and Milošević that prove they want to divide Bosnia. He threatened to present it publicly "if Franjo Tuđman do another blunder to HSP". It has never been presented.[48]

In 1997, Ivan Zvonimir Čičak, president of the Croatian Helsinki Committee, and historian Ivo Banac, claimed that a well known Croatian general, whose name they did not want to tell, heard the complete recording of Karađorđevo meeting in a ministry of a foreign country. Čičak claimed that the recordings were secretly taken by an officer of the Yugoslav army who was murdered in 1993. The existence of recordings has never been proved, and the name of the general or of the foreign country has never been announced.[49]

Stjepan Mesić

The best known critic of Franjo Tuđman in Croatian politics, because of his claimed agreement in Karađorđevo, was his successor as President of Croatia, Stjepan Mesić. At the time of the meeting, Mesić was one of Tuđman's closest collaborators and a member of Yugoslav Federal Presidency. He claims that he was the one who organized the meetings between Tuđman and Milošević.[50] On 26 March 1991, a day after the meeting, Mesić gave a comment to the Associated Press, saying that the Yugoslav republic presidents will reach an agreement on the future of the country no later than 15 May 1991.[51] In a March 1992 speech in Switzerland, Mesić denied that there was an agreement to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina: "There is no deal between Tuđman and Milošević. We talked to Milošević because we had to know what the rascal wants".[52]

In 1994, Mesić left Tuđman's party, the HDZ, to form a new party, the Croatian Independent Democrats (Hrvatski Nezavisni Demokrati, HND). Mesić stated that this decision was motivated by his disagreement with Croatia's policy on BiH, specifically Tuđman's alleged agreement with Milošević in Karađorđevo. Until then, Mesić never mentioned such an agreement in his books about the break up of Yugoslavia published in 1992 and 1994. He left HDZ three years after the Karađorđevo meeting, and after the whole Croat–Bosniak War was finished with the Washington Agreement, when Croats and Bosniaks established the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[53]

At the trial of Tihomir Blaškić, Mesić said during his testimony: "Tuđman came back from Karađorđevo that same day and he told us [...] that it would be difficult for Bosnia to survive, that we could get borders of the Banovina. Tuđman also said that Milošević, sort of in a gesture of largesse - that Croatia could take Cazin, Kladuša and Bihać, because this was the so-called Turkish Croatia and the Serbs did not need it." During the cross-examination, Mesić added: "What arrangements were reached there, I do not know. I am just aware of the consequences."[54]

Mesić testified at the trial of Slobodan Milošević that the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina was the main topic of discussion at the meeting.[55]

When Stjepan Mesić became the president of Croatia after the death of Tuđman, he testified at ICTY about the existence of a plan to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina into three parts, between Serbs and Croats, and a small Bosniak state. Stjepan Mesić claims he was the one who organized the meetings.[50] When Mesić suggested the meeting to Borisav Jović, Mesić confronted him and accused him of "arming the Croatian Serbs", Jović denied it and stated that they: "were not interested in the Croatian Serbs, but only in 65% of Bosnia-Herzegovina."[56] Mesić wrote in 2001 that the Karađorđevo and Tikveš meetings convinced Tuđman that Serbia would partition Bosnia and Herzegovina along a Serb-Croat seam with Serbia conceding to Croatia territory up to the borders of the 1939 Banovina of Croatia.[57]

Josip Manolić

Josip Manolić was the Prime Minister of Croatia at the time. In an interview he gave in October 1993, Manolić said "so far I don't know of any agreement between Milošević and Tuđman".[58] In 1994 he came into conflict with the HDZ leadership and together with Mesić formed a new party.[53]

On 3 July 2006, during the Prlić et al. trial, Manolić stated that Tuđman informed him after the meeting: "that they had reached an agreement in principle of their attitude towards Bosnia-Herzegovina and how they were to divide it, or how it was to be divided."[59] On 5 July 2006, during the cross-examination by the defence, Manolić said: "I didn't say that they had reached an agreement on division of Bosnia and Herzegovina, rather that they were discussing it. I don't know to what extent this nuance can be conveyed through translation, but to reach an agreement is a finite verb, whereas to discuss or to negotiate is something that implies that no agreement has yet been reached. It's a continuing process."[58]

Hrvoje Šarinić

Hrvoje Šarinić, former head of Tuđman's office, wrote a book Svi moji tajni pregovori sa Slobodanom Miloševićem (All my secret negotiations with Slobodan Milošević) in 1998 in which he published photographs taken in Karađorđevo, but did not write anything about the content of the meeting.[60] In his ICTY testimony and media interviews he denied that there was any formal or concrete agreement at Karađorđevo about the partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[38] Šarinić was present at the beginning of the meeting in Krađorđevo. In a 2000 interview he claimed:

I was sitting with Tuđman and Milošević 10–15 minutes (...) Tuđman attacked Milošević and told him that he knows that he, Milošević, stands behind the Log Revolution (...) but Milošević acted as a nun and said that he has nothing to do with that. (...) And then he [Tuđman] told him about the idea of Greater Serbia. Clearly, Milošević was denying everything. (...) Then Milošević - very significantly - said: 'I think that we can surely come to an understanding to solve that problems!' And then they left. (...) on our return to Zagreb, Tuđman showed me a piece of paper he received from Milošević, about the great danger of the spread of Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina. (...) Today I am almost certain that, in preparation for the meeting in Karađorđevo, Milošević forged the paper with the sole intention to pull Tuđman to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina.[61]

Two years later, after Mesić's testimony in the Hague, Šarinić commented that Tuđman did not talk much after Karađorđevo and that everything that is said about the meeting is speculation.[61]

While he was being examined by Milošević at the ICTY, Šarinić stated: "The fact that you met was no secret but what you discussed was a secret. [...] As regards Bosnia and the division of Bosnia, there was a lot of speculation about it, but no one else except the two presidents, one of whom is here, and the other in the other world, could know what they actually said."[62] Šarinić went on to say that whilst Bosnia was discussed between the presidents, only one side put any plan into practice, and that was the Serbs in ethnically cleansing and preparing Republika Srpska for annexation.[62] He claimed that whilst Tuđman was optimistic after Karađorđevo, that he thought Milošević had his "fingers crossed in his pocket". Šarinić also claimed that he did "not believe that a formal agreement was reached".[63]

Ante Marković

The former prime minister of SFRY, Ante Marković, also testified at ICTY and confirmed an agreement was made to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina between Serbia and Croatia.[64][65][66]

Ante Marković, the last Prime Minister of Yugoslavia, broke his 12-year-long silence and, at the trial of Slobodan Milošević, stated: "I was informed about the subject of their discussion in Karađorđevo, at which Milošević and Tuđman agreed to divide Bosnia-Herzegovina between Serbia and Croatia, and to remove me because I was in their way. [...] They both confirmed that they had agreed on dividing Bosnia-Herzegovina. When questioned by Chief Prosecutor Geoffrey Nice, Marković said: "Milošević admitted this immediately, while Tuđman took more time".[65][66]

According to Marković, both Tuđman and Milošević thought that Bosnia and Herzegovina was an artificial creation and the Bosniaks an invented nation. In Tuđman's view they were "converted Catholics", and in Milošević's "converted Orthodox". Since the Serbs and the Croats combined constituted a majority, the two also believed that the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina would not cause a war, and conceived an enclave for the Bosniaks. Support from Europe was expected as it did not want to see the creation of a Muslim state. Tuđman also told Marković that history would repeat itself in that Bosnia and Herzegovina would again fall "with a whisper".[65]

Marković declared that he warned both leaders that a division would result in the transformation of Bosnia into a Palestine. He told this to the Bosniak leader Alija Izetbegović, who gave him secretly made tapes of conversations between Milošević and Radovan Karadžić, discussing the JNA support of the Bosnian Serbs. He went on to say that Milošević was: "obviously striving to create a Greater Serbia. He said one thing and did another. He said that he was fighting for Yugoslavia, while it was clear that he was fighting for a Greater Serbia, even though he never said so personally to me."[65]

Other testimonies

Later, in 1993, Slaven Letica recalled this meeting, stating: "There were several maps on the table. The idea was close to the recent ideas on Bosnia-Herzegovina, either to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina into ten or fifteen [sub]units, or three semi-independent states."[67] Relaying the information from Letica, British journalist and writer Marcus Tanner notes that the meeting was not immediately significant because of any deal about Bosnia but because of no deal about Croatia, and this failure to negotiate a deal soon led to the Army leaders and Borisav Jović calling for a state of emergency to be proclaimed.[67]

Dušan Bilandžić, an advisor to Franjo Tuđman, said in December 1991 that Serbia offered an agreement on the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina at the beginning of 1991, which the Croatian side rejected. In an interview with Croatian weekly Nacional on 25 October 1996, Bilandžić said that after the negotiations with Slobodan Milošević, "it was agreed that two commissions should meet and discuss the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina". Croatian historian Ivica Lučić described Bilandžić's testimonies as contradictory.[68]

Professor Smilja Avramov, an advisor to Milošević, stated: "I did not attend the Karađorđevo meeting [...] but the group that [...] I was a part of, I assume was formed based on the agreement from Karađorđevo. [...] I talked about how we discussed borders in principle, whether they can be drawn based on the revolutionary division of Yugoslavia or based on international treaties"[69]

Borisav Jović, a close ally and advisor to Milošević, was not present at the meeting but testified in the Milošević trial that he: "was never informed by Milošević that at a possible meeting of that kind they discussed -- he discussed -- possibly discussed with Tuđman the partition of Bosnia" He also claimed he believed that Mesić was not telling the truth about the meeting because Mesić had a political clash with Tuđman."[70]

Historian assessments

In 2006, Ivo Banac wrote that it is possible that an "agreement with Milošević at Karađorđevo [...] was the final step" in the direction of the "reasonable territorial division" mentioned by Tuđman in his 1981 book.[71][72]

In 1997, Marko Attila Hoare wrote that, in the context of the conflict in Croatia, the meeting can be viewed as an attempt by Tuđman to prevent a Serbo-Croatian war where Croatia would face the full might of the Yugoslav army. Discussion of the partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina is therefore seen by some people as an attempt to avoid this conflict.[73]

British historian Mark Almond wrote in 2003 that "this meeting has attained mythical status in the conspiracy theory literature which equates Tuđman and Milošević as partners in crime in the demonology of the Balkan conflict. [...] Whatever was discussed it is clear that nothing of substance was agreed."[74]

In 2006, Croatian writer Branka Magaš wrote that Tuđman continued to pursue a settlement with Milošević, of which the cost was borne by Bosnia and Herzegovina, and a considerable part of Croatia itself.[75]

In 2010, historian Sabrina P. Ramet noted that while there is sufficient information to indicate that the partition of Bosnia was a topic of some interest in Croatia and Serbia at the time, subsequent to the meeting, Milošević did not behave as if he had an agreement with Tuđman.[76]

Croatian-American historian James J. Sadkovich noted in his biography of Tuđman that the claims of partition of Bosnia came from persons that were not present at the meeting and there is no record of this meeting that proves an existence of such an agreement.[77]

Notes

- Bilandžić 1999, p. 763.

- "Iz krize bez primjene sile" (in Croatian). Vjesnik. 1991-01-21.

- "BiH i Hrvatska predlažu prolongiranje roka" (in Bosnian). Oslobođenje. 1991-01-22.

- "Susret Milošević -- Izetbegović" (in Bosnian). Oslobođenje. 1991-01-23.

- "Razlike nisu prepreka dijalogu" (in Bosnian). Oslobođenje. 1991-01-24.

- Jović, Borisav (1995). Poslednji dani SFRJ (in Serbian). Beograd: Politika.

- Ćosić, Dobrica (2002). Pišćevi zapisi (1981-1991). Beograd: Filip Višnjić. pp. 379–381.

- Lučić 2008, p. 114.

- Tuđman 2006, p. 131.

- Nikolić, K.; Petrović, V. (2011). Od mira do rata. pp. 138–139.

- "Intervju Stipe Mesića Asošijeted presu: Marković odlazi" (in Bosnian). Oslobođenje. 1991-03-28.

- Tanner 2001, pp. 241–242.

- Lučić 2003, p. 11.

- Bilandžić 1999, pp. 765–766.

- Lučić 2003, p. 12.

- Šarinić 1999.

- Lučić 2003, p. 8.

- Tanner 2001, pp. 242–243.

- Tuđman 2006, p. 148.

- Tuđman 2006, pp. 145–146.

- Lučić 2003, p. 14.

- "Jugojalta" (in Bosnian). Sarajevo: Oslobođenje. 1991-04-14. p. 1.

- Lučić 2003, p. 13.

- Minić, Miloš (1998). Pregovori između Miloševića i Tuđmana o podjeli Bosne u Karađorđevu 1991. Beograd: Društvo za istinu o antifašističkoj narodooslobodilačkoj borbi u Jugoslaviji (1941-1945). p. 13.

- Bilandžić, Dušan (2001). Propast Jugoslavije i stvaranje moderne Hrvatske. Zagreb. p. 527.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Čemu služe Bilandžićeve konstrukcije". NIN. 2006-08-17.

- Avramov, Smilja (1997). Postherojski rat Zapada protiv Jugoslavije. Beograd: Veternik-Ldi. p. 140.

- "Franjo Tuđman - Poziv na obranu domovine, 5. listopada 1991". YouTube. October 5, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918-2004. Indiana University Press. p. 434. ISBN 0-271-01629-9.

- Bojić, M. (2001). Historija Bosne i Bošnjaka. p. 361.

- Burns, John (1992-05-12). "Pessimism Is Overshadowing Hope In Effort to End Yugoslav Fighting". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- Blaine, Harden (1992-05-08). "Warring Factions Agree on Plan to Divide up Former Yugoslavia". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- "Prosecutor v. Tihomir Blaškić - Judgement" (PDF). United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2000-03-03. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- Williams, Kristen (2001). Despite nationalist conflicts: theory and practice of maintaining world peace. Greenwood Publishing. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-275-96934-9.

- Lučić 2003, pp. 34–35.

- Tuđman 2006, p. 159.

- Burns, John F. (July 18, 1993). "Serbian Plan Would Deny the Muslims Any State". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- Sadkovich 2007, p. 239.

- Lučić 2003, pp. 9–10.

- ICTY, Blaškić Judgement 2000, p. 37.

- Tuđman 2006, pp. 149, 155–156.

- "The prosecutor of the tribunal against Slobodan Milošević: Amended Indictment". United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2002-11-22. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- Lučić, Ivica (2013). Uzroci rata. Zagreb: Hrvatski institut za povijest. ISBN 978-953-7892-06-7.

- Tuđman 2006

- Tuđman 2006, p. 149.

- Izetbegović, Alija (2001). Sjećanja, autobiografski zapisi.

- Karabeg, Omer (2008-02-27). "Kiro Gligorov: Podela živog mesa". Radio Slobodna Evropa. Radio Free Europe. Retrieved 2014-05-22.

- Lučić 2003, pp. 22–23.

- Lučić 2003, pp. 23–25.

- Karabeg, Omer (27 February 2008). "Stjepan Mesić: Ja sam dogovorio sastanak u Karađorđevu". Radio Slobodna Evropa.

- Lučić 2003, p. 9.

- Malenica, Anita (28 September 2000). "Mesić: Izbjegli Srbi ne mogu se vratiti, a mi možemo pripojiti BiH!". Slobodna Dalmacija.

- Lučić 2003, p. 30.

- Tuđman 2006, pp. 153–155.

- "Testimony of Stjepan Mesić from a transcript of the Milošević trial". United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2002-10-02. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- Roknić, Marko (20 November 2005). "A third entity would harm Bosnia-Herzegovina". Bosnian Institute.

- Magaš & Žanić 2001, p. 11.

- ICTY Transcript & 6 July 2006.

- "Testimony of Josip Manolić from a transcript of the Prlić trial". United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2006-07-03. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- Lučić 2003, p. 10.

- Lučić 2003, pp. 33–34.

- "Testimony of Hrvoje Šarinić from a transcript of the Milošević trial". United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2004-01-22. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- "Testimony of Hrvoje Šarinić from a transcript of the Milošević trial". United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2004-01-21. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- "Marković objašnjava kako je počeo" (in Croatian). Sense Tribunal. October 23, 2003. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- "Ante Markovic's testimony". Bosnian Institute. October 24, 2003. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- "Milosevic trial hears of 'Bosnia plot'". BBC. October 23, 2003. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- Tanner 2001, p. 242.

- Lučić 2003, pp. 31–32.

- "Testimony of Smilja Avramov from a transcript of the Milošević trial". United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2004-09-08. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- "Testimony of Borislav Jović from a transcript of the Milošević trial". United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2003-11-18. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- Tuđman, Franjo (1981). Nationalism in contemporary Europe. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-914710-70-2.

- Banac, Ivo (2006). "Chapter 3: The politics of national homogeneity". In Blitz, Brad (ed.). War and change in the Balkans. Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–43. ISBN 978-0-521-67773-8.

- Hoare & March 1997.

- Almond 2003, p. 194.

- Magas, Branka (2006). "Chapter 10: The war in Croatia". In Blitz, Brad (ed.). War and change in the Balkans. Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–123. ISBN 978-0-521-67773-8.

- Ramet 2010, p. 264.

- Sadkovich 2010, p. 393.

References

- Almond, Mark (December 2003). "Expert Testimony". Review of Contemporary History. Oriel College, University of Oxford. 36 (1): 177–209.

- Bilandžić, Dušan (1999). Hrvatska moderna povijest (in Croatian). Golden marketing. ISBN 953-6168-50-2.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (March 1997). "The Croatian Project to Partition Bosnia-Hercegovina, 1990-1994". East European Quarterly. 31 (1): 121–138.

- Lučić, Ivo (June 2008). "Bosna i Hercegovina od prvih izbora do međunarodnog priznanja" [Bosnia and Herzegovina from the first elections to international recognition]. Review of Contemporary History. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 40 (1): 107–140.

- Lučić, Ivo (June 2003). "Karađorđevo: politički mit ili dogovor?" [Karađorđevo: a Political Myth or an Agreement?]. Review of Contemporary History. Zagreb, Croatia: Udruga Sv. Jurja. 35 (1): 7–36.

- Magaš, Branka; Žanić, Ivo (2001). The War in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina 1991–1995. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-8201-3.

- Sadkovich, James J. (January 2007). "Franjo Tuđman and the Muslim-Croat War of 1993". Review of Croatian History. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 2 (1): 204–245. ISSN 1845-4380.

- Šarinić, Hrvoje (1999). Svi moji tajni pregovori sa Slobodanom Miloševićem 1993-1995 [All my Secret Negotiations with Slobodan Milošević]. Zagreb: Globus international. ISBN 9536749009.

- Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia : a nation forged in war (2nd ed.). New Haven; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09125-7.

- Tuđman, Miroslav (2006). Vrijeme krivokletnika. Zagreb: Detecta. ISBN 953-99899-8-1.

- "Prosecutor v. Tihomir Blaškić - Judgement" (PDF). United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2000-03-03. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- "Testimony of Josip Manolić at the Prlić trial". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 6 July 2006.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2010). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Sadkovich, James J. (2010). Tuđman – Prva politička biografija (in Croatian). Zagreb: Večernji list. ISBN 978-953-7313-72-2.

Further reading

- Delalic, Medina (12 September 2022). "Sharing the Spoils: When Milosevic and Tudjman Met to Carve Up Bosnia". Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.