Black veganism

Black veganism in the United States is a social and political philosophy that connects the use of non-human animals with other social justice concerns such as racism and with the lasting effects of slavery, such as the subsistence diets of enslaved people enduring as familial and cultural food traditions. Sisters Syl Ko and Aph Ko first proposed the intersectional framework for and coined the term Black veganism. The Institute for Critical Animal Studies called Black veganism an "emerging discipline".

Research has found that about 8% of Black Americans are vegan or vegetarian, compared to only about 3% of other Americans.[1]

History

Veganism as a named movement historically was made up primarily of white people, and the stereotypical vegan is white; Khushbu Shah pointed out in 2018 that not until the bottom of the third page on Shutterstock was a person of color included among the images for the search term "vegan person".[2] Omowale Adewale, founder of New York City's Black VegFest, argues that there is a history of Black veganism in the US, but said in 2020 that the recent increase in Black veganism is partially because "You love to see yourself represented. That's one of the main reasons why the Black community has really galvanised around the vegan idea".[3]

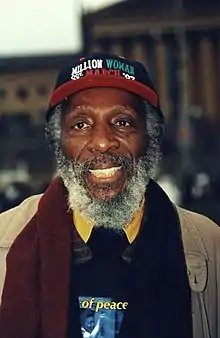

The modern Black veganism movement takes inspiration from Rastafarianism, which developed a plant-based diet known as Ital in Jamaica in the 1930s, and groups like the African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem, which has advocated strict veganism since the 1960s, and the Nation of Islam, which specifically connected choosing a plant-based diet to fighting racist oppression.[2][4][5] It also has roots in the American Civil Rights movement; Dick Gregory, who marched with Martin Luther King, Jr., argued that "Because I'm a civil rights activist, I am also an animal rights activist. Animals and humans suffer and die alike."[3] According to Amirah Mercer, by the 1980s veganism had "settled firmly into celebrity and activist pockets" among Black people in the US.[5] The 1990 hip hop song "Beef" by KRS-One, according to Keith Tucker, founder of Hip Hop is Green vegan advocacy group, influenced many in the hip hop community to think about veganism and "meat in the slave diet".[6] In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Queen Afua played an influential role in promoting Black raw veganism.[7] She advocated using food as a tool for healing Black women’s reproductive and spiritual health.[8]

Aph and Syl Ko are prominent Black philosophers, together they contributed a philosophical framework for Black veganism. Syl Ko in a 2020 presentation to the Brooks Institute describes the development of the concept of Black veganism as an intersectional theory for political and social commentary, saying that she and her sister had in 2012 first discussed the idea that "animals are raced" and in 2015 started calling that idea Black veganism.[9] Syl Ko conceptualizes Black veganism as a critique of society's perception of animals.[9] Syl Ko states in the presentation for the Brooks institute, "we are not interested in the cosmetic diversity issue that's going on in animal ethics."[9] In 2017 Aph and Syl Ko published Aphro-ism; Corey Lee Wrenn in a review said it presented Black veganism as "a political protest against the oppressiveness of animality, Eurocentric hierarchy-building, and harmful foodways."[10]

By the late 2010s research was showing that up to 8% of Black Americans identified as vegan, as compared to about 3% for the US population as a whole.[3][6] In 2017 Carol J. Adams argued, "Now is the time for us to listen to and embrace black veganism."[11]: 149 In 2021,The Washington Post, citing a Gallup report, referred to Black people as the fastest-growing demographic of vegans.[6]

Description

In the United States, Black veganism is a social and political philosophy as well as a diet.[4] It connects the use of non-human animals with other social justice concerns such as racism, and with the lasting effects of slavery, such as the subsistence diets of enslaved people enduring as familial and cultural food traditions.[3][4][5][12] Dietary changes caused by the Great Migration also meant former farmers, who had previously been able to grow or forage their own vegetables, became reliant on processed foods.[2][5] Adams described Black veganism as a "lens of race and animality" through which veganism could be understood as a radical movement for social justice.[11]: 149 Additionally, health issues within the black community have been cited as catalysts for people of color to become vegan. Diet-related conditions include diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and stroke.[13]

Syl Ko starts from a framework initially discussed by Peter Singer but which does not consider race. According to Syl Ko, Black veganism is "an animal ethic generated from within an anti-racist commitment."[9]: 2 She and her sister proposed developing a "revolutionary" concept of animal ethics that removes non-human animals from the discussion.[9]: 3 Ko told the Brooks Institute that the debate about ethical veganism was whether speciesism was just like racism or sexism; she and her sister had framed it around the idea that speciesism and racism were the same thing.[9] Syl Ko and Aph Ko conceptualized a theoretical framework for Black veganism, but in praxis there are also Black communities that define Black veganism as cultural-specific practice.[7][9] Some Black vegans that consider race in important component to their food practice, who also believe in speciesism, connect the violence of systemic racism and the legacy of slavery to the violence that is currently exerted over Black people today and non-human animals.[14][15]

According to AshEL Eldridge, an Oakland activist, the movement is about the Black community reclaiming its food sovereignty and "decolonizing" the diet of Black Americans.[6] According to Shah, the area where most vegans of color feel the greatest rift with mainstream veganism is in mainstream veganism's failure to recognize the intersectionality with other social justice issues such as food access.[2] Dr. A. Breeze Harper also attributes this spilt in vegan philosophy and praxis to the misalignment of goals by saying, "the overwhelmingly white U.S. vegan movement guides the assumption that serious dialogue around race, racism, whiteness, and racialized colonialism are unrelated to its goals."[16]

PETA columnist Zachary Tolivar noted he had often heard Black veganism called "a revolutionary act" because it often involves rejecting both family tradition and systemic oppression.[2][12] Mercer described it as "revoking my own Black card" and said that for US Black people, choosing veganism was an act of protest against disenfranchisement by governmental health care and food policy.[5]

The Institute for Critical Animal Studies called Black veganism an "emerging discipline".[17]

Influences

In 2010, two influential books, A. Breeze Harper's Sistah Vegan and McQuirter's By Any Greens Necessary were published.[4] In the anthology, Sistah Vegan, the editor Dr. A. Breeze Harper, a prominent critical race feminist scholar, argued that veganism is a tool for combating environmental injustice, health inequities, and internalized colonization.[18] In 2014 Bryant Terry wrote Afro-Vegan; Mercer described seeing the two words juxtaposed on a book cover as having "disrupted everything the mainstream had ever shown me about veganism."[5] In 2015 Aph Ko, tired of hearing that only white people were vegans, created Black Vegans Rock, initially a list of prominent Black vegans but eventually a website.[4] Two years later she and her sister Syl Ko published Aphro-ism: Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters.[10][11]

Prominent African-Americans have publicly discussed their veganism. In 2011, Oprah Winfrey's staff went vegan for a week and produced a show about the experience.[4] David Carter made headlines as the "300-pound vegan" after adopting a vegan diet in 2014.[19] In 2017, Bleacher Report published a story about multiple Black NBA players having adopted a vegan diet.[20] Beyonce has discussed her experimentation with plant-based eating.[5] Senator Cory Booker's veganism was discussed during his 2020 presidential campaign. A Los Angeles Times article featured the headline "Cory Booker could be our first vegan president."[21] When asked about it at the third Democratic presidential debate, he discussed the factory farming system.[22] New York City Mayor Eric Adams is the first vegan leader of that metropolis.[23]

Veganism was particularly embraced by the hip hop community in the late 2010s and early 2020s.[24] In 2016 "health and wellness", including a plant-based diet, was added as the 10th "element of hip hop".[24] According to hip hop artist SupaNova Slom, young Black people turned to veganism in response to their older relatives' diet-caused health issues.[6]

Appropriation

Black vegans often face exotification of their food and culture by white vegan communities and spaces, that alienates Black people from participating in the larger vegan community.[25] A prime example of the appropriation and exotification of Black vegan cooking is in the popular vegan cooking blog, Thug Kitchen. This blog written in a style "borrowed heavily from African-American culture" and which had spawned book deals, was revealed as being authored by a white couple, Michelle Davis and Matt Holloway.[2][26] Multiple critics described it as akin to blackface and pointed out the history of the use of the word "thug" as racially charged and typically used to describe Black men as criminals.[2][27][28][29] Vice pointed out that the website and cookbooks were an example of how "you don't have to look very hard to find white and non-black people profiting off of what could traditionally be deemed black culture."[29] Alice Randall said it was "perpetuating the fraud" that veganism was not present among urban Black people and it helped to drown out or distract from authentic Black vegan voices.[30]

Terry in 2014 described the blog and cookbooks as "whites masking in African-American street vernacular for their own amusement and profit", pointing out that the fact the couple had not identified themselves for two years was evidence of knowledge of the problematic nature of their behavior.[31] After years of backlash about the name, in June 2020, in the midst of the George Floyd protests, the organization announced it would no longer be called Thug Kitchen.[27][28][32] The Austin American-Statesman said, "The TK joke isn't funny."[33]

Advocacy

Hip Hop is Green is a US-based organization that uses hip hop events to promote veganism to Black youth as both a healthy choice and a political statement.[4] The group held their first event in 2009 and in 2015 held one at the White House.[6] Vegan Voices of Color argues that "mainstream veganism" is still "white veganism".[2] The Food Empowerment Project is a vegan food justice advocacy group.[2]

Black vegans of South Africa is an advocacy group for BIPOC vegans and provides a safe space to discuss issues affecting members. The group also does profiles on the black members to create greater visibility of black people in the vegan community of South Africa.

References

- "Why black Americans are more likely to be vegan". BBC News. September 10, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- Shah, Khushbu (January 26, 2018). "The Secret Vegan War You Didn't Know Existed". Thrillist. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- "Why black Americans are more likely to be vegan". BBC News. September 11, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Severson, Kim (November 28, 2017). "Black Vegans Step Out, for Their Health and Other Causes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Mercer, Amirah (January 14, 2021). "How I Found Empowerment in the History of Black Veganism". Eater. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Reiley, Laura (January 24, 2020). "The fastest-growing vegan demographic is African Americans. Wu-Tang Clan and other hip-hop acts paved the way". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Sistah vegan : black female vegans speak on food, identity, health, and society. A. Breeze Harper. New York. 2010. ISBN 978-1-59056-257-4. OCLC 818847053.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - Afua, Queen (2000). Sacred woman:a guide to healing the feminine body, mind, and spirit (1 ed.). New York: One World. ISBN 0-345-42348-8. OCLC 42291391.

- Ko, Syl (February 2020). "Brooks Congress: On Black veganism" (PDF). The Brooks Institute.

- Wrenn, Corey Lee (January 4, 2019). "Black Veganism and the Animality Politic". Society & Animals. 27 (1): 127–131. doi:10.1163/15685306-12341578. ISSN 1063-1119. S2CID 149474330.

- Ko, Aph; Ko, Syl (2017). Aphro-ism: Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters. Brooklyn, NY: Lantern. ISBN 978-1-59056-555-1. LCCN 2017013836. OCLC 1021232784.

- Toliver, Zachary (August 16, 2017). "11 Things to Expect When You're Being Vegan While Black". PETA. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Jackson, Edina Abena (February 4, 2021). "On Being Black and Vegan: The Harsh Realities of Black Veganism". Medium. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- Culture, Center for the Study of Southern. "How to Eat to Live". southernstudies.olemiss.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- Sistah vegan : black female vegans speak on food, identity, health, and society. A. Breeze Harper. New York. 2010. ISBN 978-1-59056-257-4. OCLC 818847053.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - Cultivating Food Justice : Race, Class, and Sustainability. Alison Hope Alkon, Julian Agyeman. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-262-30021-6. OCLC 767579490.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "February 2021 Top Five Books on Race and Animal Liberation | Institute for Critical Animal Studies (ICAS)". Institute for Critical Animal Studies. February 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- Sistah vegan : black female vegans speak on food, identity, health, and society. A. Breeze Harper. New York. 2010. ISBN 978-1-59056-257-4. OCLC 818847053.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - "Former NFL player believes a vegan diet could help prolong athletes' lives". FOX Sports. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Haberstroh, Tom. "The Secret (but Healthy!) Diet Powering Kyrie and the NBA". Bleacher Report. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Saad, Nardine (February 1, 2019). "Cory Booker could be our first vegan president. How very 2020". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- Samuel, Sigal (September 12, 2019). "Cory Booker was asked about veganism at the debate. He missed an opportunity". Vox. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- Starostinetskaya, Anna. "Eric Adams Makes History as New York City's First Vegan Mayor". VegNews.com. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- Rao, Vidya (February 26, 2021). "Black and vegan: Why so many Black Americans are embracing the plant-based life". Today. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Cultivating Food Justice : Race, Class, and Sustainability. Alison Hope Alkon, Julian Agyeman. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-262-30021-6. OCLC 767579490.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Dickson, Akeya (September 30, 2014). "Thug Kitchen: A Recipe in Blackface". The Root. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Shure, Marnie (June 15, 2020). "Thug Kitchen announces plans to no longer be Thug Kitchen". The Takeout. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Alam, Anam (July 13, 2020). "Thug Kitchen Has Changed its Name After Years of Backlash". The Vegan Review. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Sowunmi, Jordan (October 3, 2014). "'Thug Kitchen' Is the Latest Iteration of Digital Blackface". Vice News. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Green, Penelope (October 21, 2015). "Thug Kitchen: Veganism You Can Swear By". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Terry, Bryant (October 10, 2014). "The problem with 'thug' cuisine". CNN. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Callahan, Chrissy (June 16, 2020). "Popular food bloggers to change 'racist' website name after defending it for years". Today. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Broyles, Addie (June 15, 2020). "'Thug Kitchen' authors finally change name, but it took too long". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved June 14, 2021.