Mishar Tatars

The Mishar Tatars (endonyms: мишәрләр, мишәр татарлары, mişärlär, mişär tatarları), previously known as the Meshcheryaki (мещеряки), are the second largest subgroup of the Volga Tatars, after the Kazan Tatars. Traditionally, they have inhabited the middle and western side of Volga, including the nowadays Mordovia, Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, Ryazan, Penza, Ulyanovsk, Orenburg, Nizhny Novgorod and Samara regions of Russia. Many have since relocated to Moscow.[4] Mishars also comprise the majority of Finnish Tatars and Tatars living in other Nordic and Baltic countries.[5]

мишәрләр, мишәр татарлары, татарлар

mişərlər, mişər tatarları, tatarlar | |

|---|---|

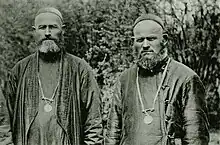

Mishar Tatar couple, late 1800s. | |

| Total population | |

| apprx. 2.3 million (or 1/3 of Volga Tatars) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1.5–2.3 million[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Mishar dialect of Tatar, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam[2][3] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kazan Tatars, Kryashens | |

Mishars speak the western dialect of the Tatar language and like the Tatar majority, practice Sunni Islam. They have at least partially different ethnogenesis from the Kazan Tatars, though many differences have since disappeared. In the 1897 census, their total number was 622,600. The estimates have varied greatly, mainly because they are often identified simply as Tatars.

Etymology

Linguist J. J. Mikkola thought the name might come from a reconstructed Mordvinic word ḿeškär, meaning "beekeeper", and thus can be connected to the Finnic tribe Meshchera. A. M. Orlov has also connected the Mishar Tatars to Meshchera, but he thinks it was a Turkic tribe rather. Orlov, Tatishev and Karamzin in addition connect it to the Don Cossacks, who allegedly were largely formed by "Meshchera Tatars". The name was also the center of the Mishar populated Kasim Khanate, Gorodets Meshchyorsky. (Tatar: Mişär yortı[6]). It might eventually come from the name of a Eastern-Hungarian tribe, the Madjars.[7][8][9][10][11]

Mishars living separately from Kazan Tatars do not call themselves Mishars, they consider themselves simply Tatars. The Tatar Turkologist of the early 19th century Akhmarov believed that the name "mishar" has a geographical character and originates from the historical region of Meshchera. [12]

"Mişär" most likely comes from the Kazan Tatars. Previously, in Russian sources, they were known as the Meshcheryaki (мещеряки).[13][14]

Other former confessional names among Mishar groups are the regional tömän (Tyumen), alatır (Alatyr), and general term möselman (Muslim). Some also called themselves "Nogay" (or Nugay), referring to Nogais that populated the Kasim Khanate, and possibly mixed with them.[15][16][17][18] In some sources, Mishars are known as "Kasimov Tatars", which was a "transitional group between Kazan Tatars and Mishar Tatars".[19]

The Mishars themselves mostly identify as Tatar, which they adopted from the Russians before other Tatar groups usually in the late 1800s. However, in the 1926 census, 200,000 called themselves "Mishars". The Tatar name originates from the time of Golden Horde, when the feudal nobility used it for its population. Later, Russian feudals and the Tsar government started using the name, though many of them still called themselves möselman or mişär instead.[20][21][22][23]

In 2006, based on a single interview done in an ethnically diverse Chuvash village, the Mishars saw Islam central to their identity; they stated that Kryashens, the Christian Tatars, were not Tatars at all. They themselves identified as "Tatar", and the term Mishar only came up after repeated questioning.[24]

History

Mishars are the second main subgroup of Volga Tatars, the other one being the Kazan Tatars. They differ mainly in living locations and dialect, though the Mishars also have at least partially different ethnogenesis from the Kazan Tatars.

Regional formation

The formation of the group took place in the forest-steppe zone on the west side of the Sura river, along the tributaries of the Oka. Individual nomadic groups began to move to this area inhabited by the Finnic peoples at the beginning of the 11th century. During the Golden Horde, Kipchaks moved to the region and founded e.g. Temnikov, Narovchat, Shatsky and Kadom fortresses. After the Golden Horde weakened, they became subjects of Russia, who farmed the land and paid the yasak tax or performed military service.[25]

The ethnic character of the Mishars was mostly finally formed during 1400–1500 in Qasim Khanate. After migration waves from late 1500s to 1700s, they settled especially on the right bank of Volga and Urals. Increased contacts with Kazan Tatars made these two groups even closer, and thus, "Tatar nation" was born; eventually replacing previously used regional names.[26][15]

Historian Alimzhan Orlov thinks the Mishars of Nizhny Novgorod Oblast are "real Mishars". G. Ahmarov says that Mishars arrived in Novgorod in early 1600s, though some of them might have already been on the territory before; Tatars who called themselves the Meshcheryaks had settled to the deserts in the eastern part of the region already before the Invasion of Kazan (1552). In remaining texts, they recall “with great longing the happy life of their ancestors in the Kazan Khanate".[8][27]

Ancestors

The origin of the Mishar Tatars has remained a point of controversy for years.[28]

R. G. Muhamedova thought that the main components for their ethnogenesis are Bolgars, Kipchaks, Burtas, and Madjar. Her assumption was, that during the collapse of the Golden Horde, the Bolgars who lived on the Sura River ended up in the area where the city of Naruchad was later founded. Here, they partially assimilated into the local population.[29]

Researchers such as Velyaminov-Zernov, Radlov and Mozharovski all thought that Mishars were originally a "Tatarized" part of the Finnic Meshchera.[30][31] M. Zekiyev, G. Ahmarov ja A. Orlov all questioned the idea of the Meshchera-theory as such.

Zekiyev states: "If this theory proves to be true, there must be clear traces of Mordvinic or other Finno-Ugric elements among the Tatars, but there are none". Ahmarov also didn't think it was possible that Meshchera could have adopted Tatar language. Conversely, he suggested that their ancestors could be "Asian nomads, that flooded Europe and settled in Akhtuba under Golden Horde, and after this, with the lead of Qasim Khan, in the territory of Oka river where they became known by the city name, Gorodets Meshchyorsky. (Tatar: Mişär yortı[6]).[32][33]

The theory of A. Orlov is as follows then: The ancestors of Mishar Tatars are formed by Cumans and Meshchera. However, Orlov denies the Finnic background of the tribe. He thinks Meshchera was all along a Turkic tribe (Polovtsian), that by Ivan the Terrible, were named as Mari/Tsheremis. Orlov states, that Mishars originate from "ancient Meshchera", which is first mentioned in Golden Horde. He also proposes, that these Turkic Meshchera largely formed the Don Cossacks, also allegedly known as the "Meschera Cossacks", even before the time of Kasim Khanate. These Cossacks then would have ended up in the Khanate, transferred by Vasily I of Moscow. Based on Orlov's text, he is not alone with the theory. A. Gordeyev connects the formation of Cossacks to Golden Horde and Tatishev made a connection between "Meshchera Tatars" and Don Cossacks. Karamzin, according to him, wrote the following: "Cossacks are just Meschera Tatars". Orlov also states however, that not all ancestors of Nizhny Novorod Mishars are from Meshchera, rather, some can be traced back to Volga Bulgaria, and others to Siberia.[8][9][34][35][32][36]

Theory about the Golden Horde unifies researchers. A. Halikov, F. Gimranov and H. Aydullin thought, that in addition to Kasimov, Mishars originate at least partially from Mukhsa Ulus. UCLA Center for Near East Studies states that Mishars most likely descent from the Kipchaks of Golden Horde, that settled on the West side of the Volga.[37][38][39]

The Hungarian theory exists also. Friar Julian describes Eastern Hungarians he found in Bashkiria in 1235. They spoke to him Hungarian and their language remained mutually intelligible. Some scientists of the 19th and 20th centuries, based on equivalency of the Turkic ethnonym Madjar (variants: Majgar, Mojar, Mishar, Mochar) with the Hungarian self-name Magyar, associated them with Hungarian speaking Magyars and came to a conclusion that Turkic-speaking Mishars were formed by a Turkization of those Hungarians who remained in the region after their main part left to the West in the 8th century..[10][11] The shift magyar>mozhar is natural for Hungarian phonology and this form of the ethnonym was in use until they shifted to Tatar in 15-16th centuries.[40] The existence of the ethnic toponyms mozhar, madjar to the east of Carpathian region proves this.[41] The presence of early medieval Hungarian culture is attested by archeological findings in Volga-Ural region.[42] The influence of Hungarian language resulted in forming definite conjugation in Mordvinic languages which is found only in Ugric languages. Medieval Hungarian loans are found in Volga Bulgarian and Mordvinic languages.[43]

Orlov thought that the ancestors of Mishars merged with the Madjars in Meshchera.[33]

The ethnogenesis of Kazan Tatars and Mishars is said to differ at least to some degree. G. Tagirdzhanov proposed, that they both originally came from the population of Volga Bulgaria, and Mishars from its Esegel tribe.[44]

Radlov noted that the Mishar-Tatar dialect is one of the closest to the Cuman language used in Codex Cumanicus.[45]

Culture

Like the Tatar majority, Mishars also are Sunni Muslim.[24]

The Mishars speak the western dialect of the Tatar language. (The Mishar Dialect). It is further divided into several local dialects. The Western dialect is characterized by the absence of the labialized [ɒ] and the uvular [q] and [ʁ] found in the Middle Tatar dialect. In some local dialects there is an affricate [tʃ], in others [ts]. The written Tatar language (ie the Kazan dialect) has been formed as a result of the mixing of central and western dialects. The Mishar dialect, especially in the Sergach area, has been said to be very similar to the ancient Kipchak languages.[46][47][48][49] Some linguists (Radlov, Samoylovich) think that Mishar Tatar belongs to the Kipchak-Cuman group rather than to the Kipchak-Bulgar group.[50]

Material from the second half of the 18th century on the Mishar dialect shows references to the Kasimov dialect, which has since disappeared, and especially to the Kadom area. Russian loanwords also appear.[51]

G. N. Ahmarov noticed a similarity in the Mishar and Kazakh cultures in the national dress of women and in the ancient Kipchak words, which are not found in the Kazan Tatar dialect, but are in the center for the Kazakhs, as well as Siberian Tatars and Altai people.[51]

Russian and Mordvian influences have been observed in Mishar architecture, house construction and home decoration. Mishar tales often contain signs of paganism and a lot of animal motifs. Social satire has also been popular. It usually targetes the rich and spiritual leaders. Folk poetry is wistful, about the home region and miserable human fates. The wedding songs of the Mishar people are very similar to the songs of the Chuvash. According to Orlov, the Mishars resemble the Karaites and the Balkars because of their language, traditional food, and the naming of the days of the week. A. Samoylovich writes; "The individual name system of the days of the week is observed in a wide area, from the Meshcheryaks of the Sergach region of Nizhny Novgorod province to the Turks of Anatolia and the Balkan Peninsula."[52][53][51][33]

Even though the Mishars have many different ethnic traits, they are (like Balkars) said to be one of the "purest representatives" of ancient Kipchaks today. Orlov states: "Nizhny Novogord Tatars are one of the original Tatar groups, who maintain the continuity of Kipchak-Turkic language, culture and tradition."[52][54]

A. Leitzinger thinks Mishars have more Kipchak in their dialect, where as Bolgar influence possibly is found better among the Kazan Tatars.[55]

Mishars and Russians

Accordin to Leitzinger, Mishars are traditionally maybe slightly more "symphatetic" to Russians than Kazan Tatars. These two groups have lived next to each other and therefore the Mishars have been influenced by them. Due to this, the Kazan Tatars have thought, maybe condescendingly, that Mishars are "half Russian". Mishars are not however so called "Russified Tatars", but still maintain their Kipchak-Turkic language and Sunni Islamic faith.[52]

Mishars are known to have partaken in the Cossack army of Stenka Razin during the 1670–1671 uprising, and probably also in other revolutions in Russian Empire. In 1798-1865, they formed the "Bashkir-Meshcheryaki Army" (Башкиро-мещерякское войско), which was an irregural formation, but took part for example in the French Invasion of Russia. (1812).[56]

Orlov says that "Meshchera Tatars" were in the Cossack army of Russian conquest of Siberia. Orlov has also gave a simple statement relating to this; "The ancestors of Mishars are the Don Cossacks".[9][57]

In some sources, Mishars are known as "Kasimov Tatars", since they were formed there. However, the formation, also known as Qasıym Tatars, was eventually a separate Tatar group; according to S. Ishkhakov, an "ethnically transitional group between Kazan Tatars and Mishar Tatars." Kasimov Tatars took part in the Conquest of Kazan and in wars against Sweden with Ivan the Terrible.[19]

In 1400-1500s, the Tatars of Kasim Khanate operated as representatives and translators in Russian court.[58]

Population

Since World War II, estimates of the number of Mishars have varied; 300,000 - 2,000,000. The census has been complicated by them sometimes being counted as their own group (Mishar/Mescheryaki) and sometimes as Tatars in general. Merging with the people of Kazan has also contributed to the matter. In 1926 cencus, there were 200 000 Mishars, but the number was thought to be higher in reality, because not everyone identified as Mishar. In 1897, the number of "Mishars" had been 622 600.[59][60]

Traditionally, the Mishars have inhabited the western side of the Volga River. Majority of the Nizhny Novgorod Mishars currently live in Moscow.[61]

DNA Studies

A genetic analysis found that the medieval Hungarian Conqueror elite is closely related to Turkic groups in the Volga region, notably Bashkirs and Volga Tatars, which, according to the study, can be modeled as ~50% Mansi-like, ~35% Sarmatian-like, and ~15% Hun/Xiongnu-like. The admixture event is suggested to have taken place in the Southern Ural region at 643–431 BCE, which is "in agreement with contemporary historical accounts which denominated the Conquerors as Turks".[62]

Notable Mishar Tatars

_18.jpg.webp)

- Sadyk Abelkhanov (1915–1943) – gunner, sergeant[64]

- Oleg Anderzhanov (b. 1969) – photographer, editor[65]

- Khaydar Bigichev (1949–1998) – singer[66]

- Husain Faizkhanov (1823–1866) – historian, philologist[67]

- Lotfulla Fattakhov (1918–1981) – painter[68]

- Rifat Fattakhov (b. 1966) – journalist, cultural worker[69]

- Rifat Muhametzhanov (b. 1938) – public servant[65]

- Rauza Mustafina (b. 1941) – cultural worker[70]

- Alimzhan Orlov (b. 1929) – historian[65]

- Ramil Sadekov (b. 1972) – imam[71]

- Shamil Sasykov (b. 1948) – wood carver[65]

- Rashid Vagapov (1908–1962) – singer[65]

Finnish Mishars

The Tatar diaspora in Finland has most of its roots in the Mishar Tatar villages of Nizhny Novgorod Oblast.[72] A nickname for such Mishars is "Nizhgar" / Nizhgarlar". (Нижгар / Нижгарлар).[73]

A project focused on Nizhny Novgorod Mishars, which historian Alimzhan Orlov calls "the pure Mishars"[8], is tatargenealogy.ru, created by Ruslan Akmetdinov.[74]

See also

Literature

- Leitzinger, Antero: Mishäärit – Suomen vanha islamilainen yhteisö. (Sisältää Hasan Hamidullan ”Yañaparin historian”. Suomentanut ja kommentoinut Fazile Nasretdin). Helsinki: Kirja-Leitzinger, 1996. ISBN 952-9752-08-3.

- Орлов, Алимжан Мустафинович: Нижегородские татары: этнические корни и исторические судьбы. Н. Новгород : Изд-во Нижегор. ун-та, 2001. ISBN 5-8746-407-8 Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: length, OCLC 54625854 (Archived online version)

References

- Encyclopedia of Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups around the World, 2nd Edition: Ethnic and National Groups around the World, 2016, page 273

- "Selçuk Üni̇versi̇tesi̇". Archived from the original on 2018-01-31. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- Vovina, Olessia (September 2006). "Islam and the Creation of Sacred Space: The Mishar Tatars in Chuvashia" (PDF). Religion, State & Society. Routledge. 34 (3). doi:10.1080/09637490600819374. ISSN 1465-3974. S2CID 53454004. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Leitzinger 1996, p. 6 (S. Ishkhakov)

- Larsson, Göran (2009). Islam in the Nordic and Baltic Countries. Routledge. pp. 94, 103. ISBN 978-0-415-48519-7.

- Рахимзянов Б. Р. Касимовское ханство (1445—1552 гг.): Очерки истории. — Казань: Татарское книжное издательство (Идел-пресс), 2009. — 208 с

- Fasmer, Maks: Etimologitšeski slovar russkogo jazyka, tom 2, p. 616, 630. Moskva: Progress, 1986.

- "Алимжан Орлов: Нижегородские татары - Потомки древней Мещеры".

- Орлов, Алимжан. "Нижегородские татары: этнические корни и исторические судьбы: Мещера – прародина нижегородских татар". Archived from the original on 2012-06-08.

- Mirfatyh Zakiev. (1995) ETHNIC ROOTS of the TATAR PEOPLE. In: TATARS: PROBLEMS of the HISTORY and LANGUAGE. Kazan.

- Кушкумбаев А.К. «По Преданиям древних они знают, что те венгры произошли от них…» К вопросу о восточных мадьярах. 3. NEMZETKÖZI KORAI MAGYARTÖRTÉNETI ÉS RÉGÉSZETIKONFERENCIA, Budapest 2018.ISBN 978-963-9987-35-7

- Кадимовна, Салахова Эльмира (2016). "Проблема происхождения татар-мишарей и тептярей в трудах Г. Н. Ахмарова". Историческая этнология. 1 (2): 349–362. ISSN 2587-9286.

- Narody mira: Narody jevropeiskoi tšasti SSSR, II, p. 638. Moskva: Nauka, 1964.

- Leitzinger 1996, pp. 33-34

- "Мишәрләр".

- Gosudarstvennyje i titulnyje jazyki Rossii, p. 355. Moskva: Academia, 2002. ISBN 5-87444-148-4.

- "Мишари и Касимовские татары".

- Leitzinger 1996, p. 31

- Leitzinger 1996, p. 8-9 (Salavat Ishkhakov)

- Narody jevropeiskoi tšasti SSSR II, s. 636. Moskva: Nauka, 1964.

- Halikov, A. H. 1991: Tataarit, keitä te olette? Suomeksi tekijän täydentämänä toimittaneet Ymär Daher ja Lauri Kotiniemi. Abdulla Tukain Kulttuuriseura r.y.

- "Мишари".

- Rorlich, Azade-Ayshe (1986). "Excerpts from "The Volga Tatars, a Profile in National Resilience"".

- Vovina, Olessia (2006). "Islam and the Creation of Sacred Space: The Mishar Tatars in Chuvashia" (PDF).

- Narody jevropeiskoi tšasti SSSR II, pp. 638, 640. Moskva: Nauka, 1964.

- Narody Rossii: entsiklopedija, p. 322. Moskva: Bolšaja Rossijskaja entsiklopedija, 1994. ISBN 5-85270-082-7.

- Орлов, Алимжан. "Нижегородские татары: этнические корни и исторические судьбы: Глава I. Поиск истоков: находки и проблемы". Archived from the original on 2012-06-08.

- Salakhova, Elmira K. (2016). ПРОБЛЕМА ПРОИСХОЖДЕНИЯ ТАТАР-МИШАРЕЙ И ТЕПТЯРЕЙ В ТРУДАХ Г.Н. АХМАРОВА [The origin of Mishar Tatars and Teptyars in the work of G. N. Akhmarov] (PDF). Historical Ethnology (in Russian). Kazan: State-funded institution Shigabutdin Marjani Institute of History of the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences. 1 (2): 349. ISSN 2619-1636. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Р. Г. Мухамедова Татары-мишари. Историко-этнографическое исследование. — М.: «Наука», 1972

- Leitzinger (Salavat Ishakov) 1996, p. 7

- Орлов, Алимжан. "Нижегородские татары: этнические корни и исторические судьбы: Глава I. Поиск истоков: находки и проблемы". Archived from the original on 2012-06-08.

- M. Z. Zekiyev Mişerler, Başkurtlar ve dilleri / Mishers, Bashkirs and their languages Archived 2014-04-08 at the Wayback Machine. In Türkiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi 73–86 (in Turkish)

- Орлов, Алимжан. "Нижегородские татары: этнические корни и исторические судьбы: Маджары и мещера – кипчакские племена". Archived from the original on 2012-06-08.

- Орлов, Алимжан. "Нижегородские татары: этнические корни и исторические судьбы: Заключение". Archived from the original on 2012-06-08.

- Рахимзянов Б. Р. Касимовское ханство (1445—1552 гг.): Очерки истории. — Казань: Татарское книжное издательство (Идел-пресс), 2009. — 208 с

- Орлов, А. М. "Нижегородские татары: этнические корни и исторические судьбы".

- Leitzinger 1996, p. 33

- Goroda Rossii: entsiklopedija, p. 547. Moskva: Bolšaja Rossijskaja Entsiklopedija, 1994. ISBN 5-85270-026-6.

- Agnes Kefeli: "Tatar", UCLA Center for Near East Studies. [Published: Wednesday, January 11, 2012]

- Rastoropov, Aleksandr (2015). Issues of early ethnic history of the Hungarians-Magyars (in Russian). Povolzhskaya Arkheologiya. №1 (11). Kazan. p. 82.

- Шушарин, В. П. Ранний этап этнической истории венгров. Проблемы этнического самосознания. Москва, 1997

- Olga V. Zelencova ’Magyar’ jellegű övdíszek Volga menti finn nyelvű népek temetőiből a Volga jobb partvidékéről. 3. NEMZETKÖZI KORAI MAGYARTÖRTÉNETI ÉS RÉGÉSZETIKONFERENCIA, Budapest 2018.ISBN 978-963-9987-35-7

- Серебренников Б.А. Исторические загадки // Советское финноугроведение. –1984. – № 3. – Москва: Наука. – p. 69–72

- Salakhova, E.K. (2016). "The origin of Mishar Tatars and Teptyars in the work of G.N. Akhmarov". 17.3.2023.

- "Публикация ННР О языке куманов: По поводу издания куманского словаря". books.e-heritage.ru. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- Jazyki Rossijskoi Federatsii i sosednih gosudarstv. Tom 3, p. 68. Moskva: Nauka, 2005. ISBN 5-02-011237-2.

- Jazyki mira: Tjurkskije jazyki, p. 371. Moskva: Indrik, 1997. ISBN 5-85759-061-2.

- Bedretdin, Kadriye (toim.): Tugan Tel - Kirjoituksia Suomen tataareista. Helsinki: Suomen Itämainen Seura, 2011. ISBN 978-951-9380-78-0. (p. 265).

- Leitzinger 1996, p. 35-37

- Махмутова Л. Т. Опыт исследования тюркских диалектов: мишарский диалект татарского языка. — М.: Наука, 1978,

- Орлов, Алимжан. "Нижегородские татары: этнические корни и исторические судьбы: Глава I. Поиск истоков: находки и проблемы". Archived from the original on 2012-06-08.

- Leitzinger 1996, pp. 35-37

- Р. Г. Мухамедова "Татары-мишари. Историко-этнографическое исследование. — М.: Наука, 1972.

- Орлов, Алимжан. "Нижегородские татары: этнические корни и исторические судьбы: Маджары и мещера – кипчакские племена". Archived from the original on 2012-06-08.

- Leitzinger 1996, p. 37

- Leitzinger 1996, pp. 10 (Ishakov), 34 (Leitzinger)

- "Нижегородские татары в XXI веке".

- Leitzinger 1996, pp. 8 (Ishakov), 35 (Leitzinger)

- Leitzinger 1996, p. 34

- "Мишәрләр".

- Leitzinger 1996, p. 44

- Kristó, G. Hungarian History in the Ninth Century. (Szegedi Középkorász Műhely, 1996). Cited in Neparáczki, E., Maróti, Z., Kalmár, T. et al. "Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports 9, 16569 (2019). doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53105-5

- "Фаттахов Рифат Ахметович".

- Абельха́нов Садык // Герои Советского Союза: Краткий биографический словарь / Пред. ред. коллегии И. Н. Шкадов. — М.: Воениздат, 1987. — Т. 1 /Абаев — Любичев/. — С. 18. — 911 с. — 100 000 экз. — ISBN отс., Рег. № в РКП 87-95382

- "Cвященные ветла и камень Тараташ (село Актуково)".

- "Бигичев Хайдар Аббасович(1949-1998)".

- "ХУСАИН ФАИЗХАНОВ" (PDF).

- Safarov, Marat. "LOTFULLA FATTAHOV: MARKING THE CENTENARY OF THE ARTIST" (PDF).

- "Рифат Фаттахов: «Состояние татарской эстрады – вопрос политической выживаемости нации»". 2016.

- "Священный дом Садек-абзи Абдулжалилова(село Овечий Овраг)".

- "Село Урга(Ыргу авылы) фото и видео".

- Bedretdin, Kadriye (toim.): Tugan Tel - Kirjoituksia Suomen tataareista. Helsinki: Suomen Itämainen Seura, 2011. ISBN 978-951-9380-78-0. (preface)

- "Нижегородские татары кто они?".

- Akmetdinov, Ruslan. ""Projects to preserve the history and culture of the Nizhny Novgorod Tatars" (in Russian)".