Merger of the KPD and SPD

The Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) merged to form the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) on 21 April 1946 in the territory of the Soviet occupation zone. It is considered a forced merger.[1] In the course of the merger, about 5,000 Social Democrats who opposed it were detained and sent to labour camps and jails.[2]

Pieck and Grotewohl shake hands during the unification ceremony | |

| Type | Unification treaty |

|---|---|

| Context | Merger of the KPD and SPD into the Socialist Unity Party of Germany |

| Signed | 21 April 1946 |

| Location | Admiralspalast, Berlin, Soviet occupation zone |

| Mediators | Soviet Union |

| Signatories |

|

| Parties | |

| Languages | German |

Although nominally a merger of equals, the merged party quickly fell under Communist domination. The SED became the ruling party of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1949; by then, it had become a full-fledged communist party – for all intents and purposes, the KPD under a new name. It developed along lines similar to other Communist Parties in what became the Soviet Bloc. The SED would be the only ruling party of the GDR until its dissolution after the Peaceful Revolution in December 1989.

Background

Among circles of the workers' parties KPD and SPD there were different interpretations of the reasons for the rise of the Nazis and their electoral success. A portion of the Social Democrats blamed the Communists for the devastation of the final phase of the Weimar Republic.[3] The Communist Party, in turn, insulted the Social Democrats as "social fascists" ("Sozialfaschisten"). Others believed that the splitting of the labour movement into the SPD and KPD prevented them effectively opposing the power of the Nazis, made possible by the First World War.

In 1945 there were calls in both the SPD and KPD for a united workers' party. The Soviet Military Administration in Germany initially opposed the idea because they took it for granted that the Communist Party would, under their guidance, develop into the strongest political force in the Soviet occupation zone. However, the outcomes of the elections conducted in Hungary and Austria in November 1945, and especially the poor performance of the Communist parties, demonstrated the urgent need for a change of strategy by the Communist party.[4] Both Stalin and Walter Ulbricht recognized the "Austria hazard" („Gefahr Österreich“)[5] and launched in November 1945, a campaign to enforce a unification of the two parties in order to secure the leading role of the Communist party.

Preparation for the merger

Under heavy pressure from the Soviet occupation forces and the Communist Party leadership, and with the support of some leading Social Democrats, working groups and committees were formed at all levels of the parties, whose declared aim was to create a union between the two parties. Many Social Democrats unwilling to unite were arrested in early 1946 in all areas of the Soviet occupation zone.[6]

On 1 March 1946, a chaotic conference of SPD party officials, convened on the initiative of the Communist and SPD leaderships, was held in the Admiralspalast, Berlin. The meeting voted to arrange a vote of SPD party members, both in the Soviet occupation zone and across Berlin, on the proposed merger with the Communist Party.[7] On March 14, 1946 the Central Committee of the SPD published a call for a merger of the SPD and KPD.[8] A ballot was scheduled to take place of SPD members in Berlin on 31 March 1946. In the Soviet sector (subsequently known as East Berlin) Soviet soldiers sealed the ballot boxes less than thirty minutes after the polls had opened, and dispersed the queues of those waiting to vote. In West Berlin more than 70% of the SPD members took part in the vote. In the western sector, invited to vote on an immediate merger ("sofortige Verschmelzung") with the Communists, 82% of those voting rejected the proposal. However, on a second proposal for a "working alliance" ("Aktionsbündnis") with the Communists, 62% of those voting did so in support of the motion.[9]

Party unification day

On 7 April 1946 a group of SPD opponents of the merger in the western sector of Berlin met together in a school in Zehlendorf (Berlin) for a new party conference at which they elected a three-man leadership team comprising Karl Germer Jr., Franz Neumann and Curt Swolinzky. On the same date a decision in support of the merger was taken at a joint Party Conference of regional delegates from the two parties inside the Soviet occupation zone. On 19/20 October in Berlin the 15th party conference of the German Communists and the 40th party conference of the German Social Democrats decided in favour of the establishment of the merged SED.

On 21/22 April 1946 another meeting took place in the Soviet-occupied sector of Berlin at the Admiralspalast. This was the Unification congress, and it was attended by delegates from the SPD and KPD for the entire Soviet Occupation Zone, which by now was in the process of developing into the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). On 22 April 1946 the unification of the (East German) SPD and KPD was completed, to form the SED. There were over 1,000 party members in attendance of whom 47% came from the KPD and 53% from the SPD. 230 of the delegates actually came from the western occupation zones. However, 103 SPD delegates from the western zones had no democratic mandate to support merger, because of the meeting in the western sector of Berlin at Zehlendorf earlier in the month, at which delegates had backed rejection of any unification between the two political parties.[11]

The congress decided unanimously in favour of uniting the parties. The new party would include equal representation by two representatives, one from each of the component parties at every level. The party Chairmen were Wilhelm Pieck (KPD) and Otto Grotewohl (SPD), their deputies Walter Ulbricht (KPD) and Max Fechner (SPD). The handshake of the two party chairmen was embodied in the central element of the new party's logo. Following this special congress individual members of the KPD and SPD would be able to transfer their membership to the new SED with a simple signature.

Although parity of power and position between members of the two former parties continued to be applied extensively for a couple of years, by 1949 SPD people were virtually excluded. Between 1948 and 1951 "equal representation" was abandoned, as former SPD members were forced out of their jobs, denounced as "Agents of Schumacher",[12] subjected to defamation, regular purges and at times imprisonment, so that they were frightened into silence.[10] Influential party positions in the new ruling party were being given almost exclusively to former members of the KPD.[10]

Berlin, the special case

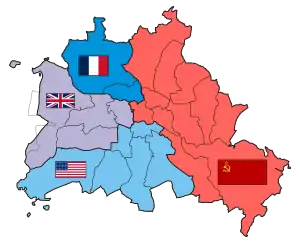

The rules agreed between the occupying powers concerning Berlin itself conferred on the city a special status which differentiated the Soviet sector of Berlin from the Soviet occupation zone of Germany which on three of its four sides adjoined it. The SPD used this fact to run a party referendum on the merger, using a secret ballot, across the whole of Berlin. The referendum was suppressed in the Soviet sector on 31 March 1946, but it went ahead in those parts of the city controlled by the other three occupying powers, and resulted in rejection of the merger proposal from 82% of the votes cast by participating SPD members.[13] The merger of the KPD and SPD to form the SED only affected the Soviet sector of the city. It was not till the end of May 1946 that the four Allies reached agreement: the western allies permitted the SED in the western sectors, and in return the Soviet Military Administration in Germany agreed to allow the SPD back into the eastern sector of Berlin.[14] That did not mean, however, that the SPD was able to operate unhindered as a political party in East Berlin.[15] Following the City council elections for Greater Berlin which took place on 20 October 1946,[16] in which the SED and SPD both competed, the total turnout was high at 92.3%. Across the city, the SPD won 48.7% of the vote while the SED won 19.8%. Of the other principal participants the CDU (party) won 22.2% and the LDP 9.3%.

As matters turned out, this was the only free election to take place across the entirety of Berlin until after 1990. Following the 1946 city council election the Soviet Military Administration and the SED in effect divided the city. In 1947 the Soviet city commander vetoed from the election of Ernst Reuter as the city's governing mayor. This was followed up by the blowing up of the City Council Building by "the masses" and the withdrawal of the Soviet city commander from the Allied Kommandatura in 1948, which turned out to be a prelude to the Soviet Union's Blockade of West Berlin.[17][18]

The SPD did indeed continue to exist in the eastern sector, but the basis for its existence changed fundamentally, since it was banned from public activity and its participation in elections was blocked by the National Front of the Democratic Republic of Germany, a political alliance created to enable minor political parties to be controlled by the SED. Some individual SPD members nevertheless continued to be politically active. Most notably, Kurt Neubauer, the regional SPD chairman in Berlin-Friedrichshain was elected to the West German Bundestag where he sat from 1 February 1952 till 16 April 1963, for much of the time as the only member of the chamber with a home address inside the Soviet occupation zone. It was only in August 1961, a few days after the Berlin Wall was erected, that the party closed his office in East Berlin,[19] but without giving up its claim to it.

Over the wall, prior to reunification in 1990, the SED played only a marginal role, even after in 1962 changing its name, for local purposes, to "Socialist Unity Party of West Berlin" (SEW / Sozialistische Einheitspartei Westberlins). Even in the aftermath of the 1968 "events" any party influence in the west proved ephemeral.

The example of Thuringia

In contrast to Berlin, for which voting results show SPD majorities rejecting the merger of the left-wing parties, the historian Steffen Kachel has identified quite a different set of results in Thurinigia, a region dominated by farms and forests, where for most of the time left-wing parties had hitherto enjoyed a lower level of overall support among the population as a whole than, typically, applied in western Europe's big industrial cities. In Berlin and nationally the SPD had already experienced lengthy periods in government during the Weimar years. Especially in Berlin city politics, the KPD had conducted an active and largely constructive role in opposition before 1933. Rivalry between SPD and KPD in Berlin was deeply rooted. In Thuringia the relationship between the two parties had been far more collaborative. There had even in 1923, and briefly, been a period of coalition between them in the regional government during the economic crisis of that time. After 1933 the collaborative relationship between the SPD and the KPD in rural Thuringia had been sustained during the twelve Nazi years (when both parties had been banned by the government) and surfaced again in 1945 until broken by the Stalinist approach presented by the creation of the SED.[20]

Party memberships at the time of the merger

In the Soviet occupation zone (excluding Greater Berlin) party membership numbers were as follows:[11]

The fact that the post-merger membership total of the merged of the SED was more than 20,000 below the combined pre-merger total memberships of the two predecessor parties reflects the fact that several thousand SPD members did not instantly rush to sign their party transfer forms.[11]

Among comrades from the SPD side, rejection of the merger was at its strongest in Greater Berlin, and it was here that the largest proportion of party members did not become members of the new merged party:[11]

During the two years following the party merger, overall membership of the SED increased significantly, from 1,297,600 to approximately 2,000,000 across East Germany by the summer of 1948, possibly swollen by prisoners of war returning from the Soviet Union or former SPD members who had initially rejected the merger having had a change of heart.

Consequences and follow-through

SPD members who had opposed the merger were prevented from refounding an independent Social Democratic party in the Soviet occupation zone by the Soviet administration. Six months after the KPD/SPD merger, in the regional elections of October 1946 the new unified workers' party did not attract as many votes as they had anticipated: despite massive support from the occupation authorities, the SED failed to gain an overall majority in any of the regional legislatures. In Mecklenburg and Thuringia their vote fell only slightly short of the required 50%, but in Saxony-Anhalt and Brandenburg, the "Bourgeois" CDU and LDP gained sufficient electoral support to form governing coalitions.[21] Even more disappointing for the new SED (party) was the electoral outcome in Greater Berlin, where the SED won only 19.8% of the vote, notwithstanding the best efforts of the authorities.

Elections in East Germany applied the "single list" approach. Voters were presented with a single list from the National Front of Democratic Germany, which in turn was controlled by the SED. Only one candidate appeared on the ballot. Voters simply took the ballot paper and dropped it into the ballot box. Those who wanted to vote against the candidate had to go to a separate voting booth, without any secrecy.[22] Seats were apportioned based on a set quota, not according to actual vote totals.[23] By ensuring that its candidates dominated the list, the SED effectively predetermined the composition of the National legislature (Volkskammer). The upside of East Germany's new voting system, in 1950, was apparent from the reported 99.6% level of support for the SED based on a turnout of 98.5%.[24]

After 1946 SPD members who had spoken up in opposition to the party merger were required to surrender their offices. Many faced political persecution and some fled. Some persisted in their political beliefs with the Eastern Bureau of the SPD which continued the political work of the party leaders and members who had fled the country. The Eastern Bureau was allowed to participate in the 1950 Volkskammer election and won 6 seats; however, the office was banned from participating from 1954 and onwards because of accusations of "espionage" and "diversion" by DDR and SED authorities and was eventually closed in 1981.

It was not until October 1989 that a Social Democratic Party was again established in the German Democratic Republic. The SPD then participated in the country's first (and as matters turned out last) free election in March 1990, winning 21.9% of the overall vote. Later in the year, in October 1990, East Germany's SPD merged with the West German SPD, in a development which mirrored the reunification of Germany itself.

The SPD in western Germany and the forced merger

The view that in 1933 long-standing political divisions on the German left had opened a path for the Nazi takeover was not restricted to the Soviet occupation zone. During 1945 there was also discussion about the relationship between the SPD and the Communist Party in the western occupation zones. In some localities (for instance Hamburg, nearby Elmshorn,[25] Munich, Brunswick and Wiesbaden) joint working groups between the two parties were set up to look at options for closer collaboration or merger.[26]

See also

References

- „Bei einer generellen Beurteilung ist »Zwangsvereinigung« der richtige Begriff. Er macht klar, dass es für die Sozialdemokraten in der SBZ damals keine Alternative gab. Sie befanden sich in einer Zwangssituation, denn unter sowjetischer Besatzung hatten sie keine freie Entscheidung darüber, ob sie dort die SPD fortführen wollten oder nicht.” Hermann Weber, Demokraten im Unrechtsstaat. Das politische System der SBZ/DDR zwischen Zwangsvereinigung und „Nationaler Front“, in: Das politische System der SBZ/DDR zwischen Zwangsvereinigung und Nationaler Front, 2006, S. 26. Auch Heinrich August Winkler schreibt, „daß der Begriff «Zwangsvereinigung» der Wahrheit nahekommt“ (zitiert n. ders., Der lange Weg nach Westen, Bd. 2. Deutsche Geschichte vom „Dritten Reich“ bis zur Wiedervereinigung, C.H. Beck, München, 4. Aufl. 2002, S. 125).

- Halb faule Lösung: Die große Koalition verbessert nach heftiger Kritik die Opferpensionen für Verfolgte des DDR-Regimes. Focus 24/2007, S. 51.

- Hermann Weber: Kommunistische Bewegung und realsozalistischer Staat. Beiträge zum deutschen und internationalen Kommunismus, hrsg. von Werner Müller. Bund-Verlag, Köln 1988, S. 168.

- Andreas Malycha/Peter Jochen Winters: Die SED. Geschichte einer deutschen Partei. C.H. Beck, München 2009. ISBN 978-3-406-59231-7, S. 28.

- Wortlaut Walter Ulbrichts siehe Mike Schmeitzner, Sowjetisierung oder Neutralität? Optionen sowjetischer Besatzungspolitik in Deutschland und Österreich 1945–1955, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2006, ISBN 978-3-525-36906-7, S. 281 f., hier S. 283.

- „Die nunmehr frei zugänglichen zeitgenössischen Dokumente über die von örtlichen sowjetischen Kommandanturen gemaßregelten und inhaftierten Sozialdemokraten geben Aufschluss darüber, wie vielerorts erst psychischer Druck der Besatzungsoffiziere die Vereinigung möglich machte.“ Andreas Malycha, Der ewige Streit um die Zwangsvereinigung, Berliner Republik 2/2006 (online).

- „In der Versammlung sozialdemokratischer Funktionäre vom 1. März 1946, die auf Betreiben der KPD- und SPD-Spitze einberufen worden war, um die Einheitsfrage offensiv zu debattieren, in deren Verlauf dann jedoch die Entscheidungskompetenz des Zentralausschusses offen in Frage gestellt und ein mehrheitliches Votum für eine Urabstimmung abgegeben wurde, kam es für Grotewohl fast zum Debakel.“ Zit. nach Friederike Sattler, Bündnispolitik als politisch-organisatorisches Problem des zentralen Parteiapparates der KPD 1945/46, in: Manfred Wilke (Hrsg.): Anatomie der Parteizentrale, Akademie Verlag, 1998, ISBN 3-05-003220-0, S. 119–212, hier S. 198.

- Berliner SPD, Archiv

- Dietrich Staritz, Die Gründung der DDR. 2. Aufl. 1987, ISBN 3-423-04524-8, S. 123.

- Publisher-editor Rudolf Augstein; Holger Kulick (18 April 2001). "PDS: Halbherzige Entschuldigung für Zwangsvereinigung: Widersprüchlich hat sich die PDS-Vorsitzende Gabi Zimmer für die Zwangsvereinigung von SPD und KPD vor 55 Jahren entschuldigt – ohne "Entschuldigung" zu sagen und ohne das Wort Zwangsvereinigung zu erwähnen. Der Sinn ist genauso verworren: Wahltaktik wird dementiert, steht aber im Hintergrund". Der Spiegel (online). Retrieved 10 December 2014.

{{cite web}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - Martin Broszat, Gerhard Braas, Hermann Weber: SBZ-Handbuch, München 1993, ISBN 3-486-55262-7.

- Kurt Schmacher was the leader of the SPD (party) in West Germany, which was by now the name being given to that part of Germany not subject to Soviet military administration.

- "Durch Manipulation, Einschüchterung und offene Repression ... Allein in den Westsektoren Berlins ist eine Urabstimmung der SPD-Mitglieder möglich, bei der 82 Prozent der Abstimmenden sich gegen eine sofortige Vereinigung aussprechen". Willy-Brandt-Haus, Verwaltungsgesellschaft Bürohaus, Berlin. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Beschluss vom 31. Mai 1946 der Alliierten Stadtkommandantur: In allen vier Sektoren der ehemaligen Reichshauptstadt werden die Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands und die neugegründete Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands zugelassen.

- Anjana Buckow, Zwischen Propaganda und Realpolitik: Die USA und der sowjetisch besetzte Teil Deutschlands 1945–1955, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-515-08261-1, page 196

- Der Landeswahlleiter in Berlin: Wahlergebnisse zur Stadtverordnetenversammlung 1946

- Gerhard Kunze: Grenzerfahrungen: Kontakte und Verhandlungen zwischen dem Land Berlin und der DDR 1949–1989, Akademie Verlag, 1999, page 16.

- Eckart Thurich: Die Deutschen und die Sieger, in: Informationen zur politischen Bildung, Vol 232, published by the Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Bonn 1991.

- Neubauer himself, with his family, was in West Berlin when the wall was suddenly put in place, and it would be many years before they were permitted to set foot in East Berlin again.

- Ein rot-roter Sonderweg? Sozialdemokraten und Kommunisten in Thüringen 1919 bis 1949 (= Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Thüringen. Kleine Reihe, Vol 29), Böhlau, Köln/Weimar/Wien 2011, ISBN 978-3-412-20544-7. See also Steffen Kachel: Entscheidung für die SED 1946 – ein Verrat an sozialdemokratischen Idealen?, in Jahrbuch für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Vol I/2004.

- Martin Broszat, Hermann Weber, SBZ-Handbuch: Staatliche Verwaltungen, Parteien, gesellschaftliche Organisationen und ihre Führungskräfte in der Sowjetischen Besatzungszone Deutschlands 1945–1949, Oldenbourg, München 1993, ISBN 3-486-55262-7, page 418.

- Sebetsyen, Victor (2009). Revolution 1989: The Fall of the Soviet Empire. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42532-5.

- Eugene Register-Guard 29 October 1989. p. 5A.

- Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p779 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- In Elmshorn the British Military Administration vetoed a merger of the parties locally.

- Hilde Wagner (interviewee). "Fragen an Hilde Wagner: Frage 4". Contemporary eye-witness report of party merger talks in Karlsruhe. Deutsche Kommunistische Partei, Karlsruhe. Retrieved 25 February 2015.