Street art in Melbourne

Melbourne, the capital of Victoria and the second largest city in Australia, has gained international acclaim for its diverse range of street art and associated subcultures. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, much of the city's disaffected youth were influenced by the graffiti of New York City, which subsequently became popular in Melbourne's inner suburbs, and along suburban railway and tram lines.

Melbourne was a major city in which stencil art was embraced at an early stage, earning it the title of "stencil capital of the world";[1] the adoption of stencil art also increased public awareness of the concept of street art.[2] The first stencil festival in the world was held in Melbourne in 2004 and featured the work of many major international artists.[2]

History

Melbourne is the proud capital of street painting with stencils. Its large, colonial-era walls and labyrinth of back alleys drip with graffiti that is more diverse and original than any other city in the world.

Around the turn of the 21st century, forms of street art that began appearing in Melbourne included woodblocking, sticker art, poster art, wheatpasting, graphs, various forms of street installations and reverse graffiti. A strong sense of community ownership and DIY ethic exists amongst street artists in Melbourne, many of whom act as activists through awareness.[4]

Galleries in the City Centre and inner suburbs now exhibit street art. Prominent Melbourne street artists were featured in Space Invaders, a 2010 exhibition of street art held at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.[5][6] Hosier Lane is Melbourne's most famous laneway for street art, however there are many other laneways in the inner city that exhibit street art.

Prominent international street artists such as Banksy (UK), ABOVE (USA), Fafi (France), D*FACE (UK), Logan Hicks,[7] Revok (USA), Blek le Rat (France), Shepard Fairey (USA) and Invader (France) have contributed work to Melbourne's streets along with visitors from all over the world, most prominently Germany, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and New Zealand.[8]

Melbourne's street art scene was explored in the 2005 feature documentary RASH. Official website (archived) RASH on Mutiny Media website

Locations

While there are small areas throughout Greater Melbourne where various forms of street art can be seen, the primary areas in which street art is most densely located include:

Public and government responses

The proliferation of street art in Melbourne has attracted supporters and detractors from various levels of government and in the broader community. In 2008 a tourism campaign at Florida's Disney World recreated a Melbourne laneway cityscape, decorated with street art. Victorian Premier John Brumby forced the tourism department to withdraw the display, calling graffiti a "blight on the city" and not something "we want to be displaying overseas."[10] Marcus Westbury countered that street art was one of Melbourne's "biggest tourist attractions and one of its most significant cultural movements since the Heidelberg School".[11]

Some street artists and academics have criticized the State Government for having seemingly inconsistent and contradictory views on graffiti.[12] In 2006, the State Government "proudly sponsored" The Melbourne Design Guide, a book which celebrates Melbourne graffiti from a design perspective. That same year, some of Melbourne's graffiti-covered laneways were featured in Tourism Victoria's Lose Yourself in Melbourne campaign. One year later, the State Government introduced tough anti-graffiti laws, with a maximum penalty of two years in prison. Possession of spray cans "without a lawful excuse", either on or around public transport, became illegal, and police search powers were also strengthened. According to Melbourne University criminologist Alison Young, the "state is profiting from the work of artists doing it, but another arm of the state wants to prosecute and possibly imprison (such) people."[12] Since laws were tightened, local councils have reported a "spike" in vandalism and an increase in tagging on commissioned murals and legal street art. Adrian Doyle, founder of the Blender Studios and manager of Melbourne Street Art Tours, believes that people who tag have become less considerate of where they put their tags for fear of being caught by police, and are "paranoid so they are taking less time—tags are less detailed".[13] In 2007, the City of Melbourne started the Do art not tags initiative—an education presentation aimed at teaching primary school students the differences between graffiti and street art.[14]

Some local councils have accepted street art and have even made efforts to preserve it. In early 2008, the Melbourne City Council installed a perspex screen to prevent a 2003 Banksy stencil art piece named Little Diver from being destroyed. In December 2008, silver paint was poured behind the protective screen and tagged with the words: "Banksy woz ere".[15] In April 2010, another stencil by Banksy, also painted in 2003, was destroyed—this time by council workers. The work depicted a parachuting rat and it was believed to be the last surviving Banksy stencil in Melbourne's laneways. Lord Mayor Robert Doyle said: "This was not the Mona Lisa. It is regrettable that we have lost it, but it was an honest mistake by our cleaners in removing tagging graffiti."[16]

The loss of these and other famous street artworks in Melbourne reignited a decade long debate over heritage protection for Melbourne's street art.[17] Planning Minister Justin Madden announced government plans in 2010 involving Heritage Victoria and the National Trust of Australia to assess street art in key locations throughout Melbourne and for culturally significant works to receive recognition for the purpose of preservation.[18] Examples of street art pieces that have been added to the Victorian Heritage Register include: the 1983 mural outside the Aborigines Advancement League building,[19][20] and a 1984 Keith Haring mural in Collingwood.[21][22]

The Melbourne City Council acknowledged the difficulties that hinder the preservation of street art, with their graffiti management plan for 2014–18 stating: "Protection of street art is not practical. The only exception may be especially commissioned works".[23]

Events

- Empty shows: illegal exhibitions held in derelict buildings since circa 2000[24]

- Stencil Festival: The first stencil art festival in the world was held in Melbourne in 2004. It was held annually until 2010.[25]

- Street video projection event: video projection events were held in Gertrude Street, Fitzroy in mid-2008.

Melbourne Stencil Festival

The Melbourne Stencil Festival was Australia's premier celebration of international street and stencil art. Since its inauguration in 2004 the festival has become an annual event, touring regional Victoria and other locations within Australia. The festival was held for 10 days each year, involving exhibitions, live demonstrations, artist talks, panel discussions, workshops, master classes and street art related films to the general public. It featured works by emerging and established artists from both Australia and around the world.[26]

Since its inception, the Stencil Festival featured some 800 works by over 150 artists, many of whom were experiencing their first major art exhibition, finding it difficult to be exhibited in major commercial galleries reluctant to display emerging art forms. The first Melbourne Stencil Festival was held in a former sewing factory in North Melbourne in 2004.[27]

- 2004 – The inaugural festival was held over three days in a warehouse in North Melbourne.

- 2005 – Featured a ten-day exhibition at the refurbished Meat Market art complex. The festival was supported by the City of Melbourne and saw more than 700 visitors on the opening night.

- 2006 – The festival moved to Fitzroy, a major location of street art in Melbourne, and was held at the Rose Street Artists Market. For the first time the four-day event was also held in Sydney. It received reviews in major mainstream media in both Melbourne and Sydney.

- 2007 – Featured a total of 75 artists from 12 countries with more than 300 works. The Melbourne event alone was attended by more than 4,000 visitors with 500 people on the opening night alone. It also attracted a wide range of media coverage including daily newspapers, community radio and street press.

- 2008 – Toured regionally with the support of Arts Victoria to Ballarat, Sale and Shepparton, and on its own effort interstate to Sydney, Brisbane and Perth.

- 2009 – The Melbourne Stencil Festival 2009 ran between 25 September and 4 October 2009.[28]

- 2010 – The Melbourne Stencil Festival transformed in the "Sweet Streets" Festival, an all encompassing festival of street and urban art. It ran between 8 – 24 October 2010.[29]

All Your Walls

An event in which the entire iconic Hosier lane was repainted by over 150 artists. Produced by Invurt, Just Another Agency and Land of Sunshine in conjunction with the National Gallery of Victoria. It ran between 27 – 29 November 2013.[30]

Notable Melbourne street artists

Other media

- RASH (2005) – Feature-length documentary film which explores the cultural value of Melbourne street art and graffiti.[24]

- Not Quite Art (2007) – ABC TV series, episode 101 explored Melbourne's street art and DIY culture.

Gallery

Keep Your Coins, I Want Change by Meek, 2004

Keep Your Coins, I Want Change by Meek, 2004 Antipoet, 2004

Antipoet, 2004 Little Diver by Banksy, 2004. Melbourne City Council moved to protect it before its destruction by vandals in 2008.

Little Diver by Banksy, 2004. Melbourne City Council moved to protect it before its destruction by vandals in 2008. Ha-Ha's iconic stencils of Ned Kelly (seen here in 2005) and other Australian bushrangers are common in Melbourne's laneways

Ha-Ha's iconic stencils of Ned Kelly (seen here in 2005) and other Australian bushrangers are common in Melbourne's laneways 70k crew members Renks and Karl 123 tag every window of an abandoned office building, 2005

70k crew members Renks and Karl 123 tag every window of an abandoned office building, 2005 Stencil by Meggs, 2006

Stencil by Meggs, 2006 Dirty Harry stencil (2006), a version of which appears on the cover of Uncomissoned Art: An A-Z of Australian Graffiti.[31]

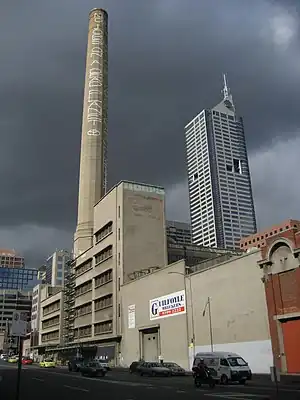

Dirty Harry stencil (2006), a version of which appears on the cover of Uncomissoned Art: An A-Z of Australian Graffiti.[31] "No jobs on a dead planet" written on the former Spencer Street coal power station, 2007

"No jobs on a dead planet" written on the former Spencer Street coal power station, 2007 Buskers perform in front of street murals near Degraves Street, 2007

Buskers perform in front of street murals near Degraves Street, 2007 Unknown artist, Fitzroy, 2007

Unknown artist, Fitzroy, 2007 Unknown artist, 2008

Unknown artist, 2008 Stickers, stencils and other forms of street art fall victim to over-tagging in Centre Place, 2008.

Stickers, stencils and other forms of street art fall victim to over-tagging in Centre Place, 2008. Union Lane project by City of Melbourne, 2008

Union Lane project by City of Melbourne, 2008 Unknown artists, 2008

Unknown artists, 2008 Multi-layered stencil of a sleeping homeless man, 2008. Social issues are a recurring theme on Melbourne's walls.

Multi-layered stencil of a sleeping homeless man, 2008. Social issues are a recurring theme on Melbourne's walls. Detail of a 2009 poster located in ACDC Lane, commenting on street violence outside Esplanade Hotel.

Detail of a 2009 poster located in ACDC Lane, commenting on street violence outside Esplanade Hotel. Street art in an abandoned warehouse in Collingwood, 2009

Street art in an abandoned warehouse in Collingwood, 2009 Unknown artist, Brunswick, 2009

Unknown artist, Brunswick, 2009 Wheatpaste by Drab, Brunswick, 2009

Wheatpaste by Drab, Brunswick, 2009 Large painted board fixed to concrete wall, Richmond, 2010

Large painted board fixed to concrete wall, Richmond, 2010 Picture frames in Presgrave Place, 2010

Picture frames in Presgrave Place, 2010 Spray paint, Northcote, 2010

Spray paint, Northcote, 2010 Light-box installations in Hosier Lane, 2010; part of the City of Melbourne's annual Laneway Commissions program.

Light-box installations in Hosier Lane, 2010; part of the City of Melbourne's annual Laneway Commissions program. Money Volcano, Phoenix the Street Artist, Hosier Lane CBD, 2010

Money Volcano, Phoenix the Street Artist, Hosier Lane CBD, 2010

See also

- Street art

- Graffiti

- Culture of Melbourne

- Lanes and arcades of Melbourne

- List of Australian street artists

- List of sporting street art in Australia

Other Australian cities:

Media

Concepts

References

- Jake Smallman & Carl Nyman (2005). "Stencil Graffiti Capital: Melbourne". Jake Smallman and Carl Nyman. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Vandalismo (8 August 2008). "Melbourne Stencil Festival". laneway. Laneway Magazine. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Banksy (24 March 2006). "The writing on the wall", The Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Innovative Theories in Art

- "Space Invaders". National Gallery of Australia. 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Space Invaders" (Video upload). Art Nation. ABC. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Home". Drago. Drago Media Kompany SRL. 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Barrett, Peter (6 February 2018). "The evolution of street art in Melbourne". peterbarrett.com.au.

- "Exploring Melbourne's Street Art Scene". 20 January 2014.

- Jewel Topsfield (1 October 2008). "Brumby slams Tourism Victoria over graffiti promotion". The Age. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Marcus Westbury (5 July 2009). "Street Art: Melbourne's unwanted attraction". Marcus Westbury. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Suzy Freeman-Greene (12 January 2008). "Urban scrawl: shades of grey". The Age. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Suzanne Robson (2 April 2009). "Taggers raid Melbourne street art". Melbourne Leader. News Community Media. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Do art not tags". City of Melbourne. 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Houghton, Janae (14 December 2008). "The painter painted: Melbourne loses its treasured Banksy". The Age.

- Hamish Fitzsimmons (30 April 2010). "Melbourne debates street art" (Transcript). Lateline. ABC. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Rachael Brown (23 June 2008). "Melbourne graffiti considered for heritage protection". ABC News (based on a report from The World Today). ABC. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Melbourne's street art gets heritage review". Arts Victoria. State of Victoria. 27 May 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Aboriginal mural". Victorian Heritage Database. State of Victoria. 13 November 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Reko Rennie (10 January 2011). "Preston mural a slice of Indigenous history" (Video upload). ABC Arts. ABC. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Keith Haring mural, east wall Main Building, Collingwood Technical School complex". Victorian Heritage Database. State of Victoria. 13 November 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Simon Leo Brown; Richelle Hunt (28 April 2010). "Melbourne's Keith Haring mural in urgent need of restoration". 774 ABC Melbourne. ABC. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Carey, Adam (4 October 2013). "Melbourne street art not meant to last, says city's graffiti management plan". The Age. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- Mutiny Media (2007). "Home". Rash The Film. Mutiny Media. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Holsworth, Mark (1 July 2014). "Stencil Festival to Sweet Streets". Black Mark Melbourne Art and Culture critic.

- Levin, Darren (12 May 2007). "Melbourne Stencil Festival". The Age.

- Ball, Caroline (8 October 2010). "Sweet Streets Festival". weekendnotes.com.

- Stencil Festival Home Archived 7 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Melbourne Stencil Festival". onlymelbourne.com.au. 8 October 2010.

- "Iconic Hosier Lane Gets A Makeover" The Herald Sun

- Uncommissioned Art: An A-Z of Australian Graffiti, australianartbooks.com.au. Retrieved 16-10-2010.

Further reading

- Nyman, Carl; Smallman, Jake (2005). Stencil Graffiti Capital: Melbourne. Mark Batty Publisher. ISBN 0-9762245-3-4.

- Dew, Christine (2007). Uncommissioned Art: The A-Z of Australian Graffiti. Melbourne University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-522-85375-9.

- Stamer, Karl (2010). Kings Way: The Beginnings of Australian Graffiti: Melbourne 1983-1993. Melbourne University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-522-85751-1.

- Ghostpatrol; Miso; Smits, Timba; Young, Alison (2010). Street/Studio: The Place of Street Art in Melbourne. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-50020-0.

- Sync; Everfresh Studio (2010). Everfresh: Blackbook: The Studio & Streets 2004–2010. Miegunyah Press. ISBN 978-0-522-85745-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dean Sunshine (2012). Land Of Sunshine: A Snapshot Of Melbourne Street Art 2010-2012. DS Publishers. ISBN 9780987382702.

- Dean Sunshine (2014). Street Art Now – Melbourne and Beyond 2012-2014. DS Tech. ISBN 9780987382719.