Mehmed IV

Mehmed IV (Ottoman Turkish: محمد رابع, romanized: Meḥmed-i rābi; Turkish: IV. Mehmed; 2 January 1642 – 6 January 1693), also known as Mehmed the Hunter (Turkish: Avcı Mehmed), was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1648 to 1687. He came to the throne at the age of six after his father was overthrown in a coup. Mehmed went on to become the second-longest-reigning sultan in Ottoman history after Suleiman the Magnificent.[1] While the initial and final years of his reign were characterized by military defeat and political instability, during his middle years he oversaw the revival of the empire's fortunes associated with the Köprülü era. Mehmed IV was known by contemporaries as a particularly pious ruler, and was referred to as gazi, or "holy warrior" for his role in the many conquests carried out during his long reign.

| Mehmed IV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ottoman Caliph Amir al-Mu'minin Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques | |||||

.jpg.webp) Portrait of Mehmed IV (oil on canvas, 1682) | |||||

| Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Padishah) | |||||

| Reign | 8 August 1648 – 8 November 1687 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ibrahim | ||||

| Successor | Suleiman II | ||||

| Regents | See list

| ||||

| Born | 2 January 1642 Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Died | 6 January 1693 (aged 51) Edirne, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Consort | Emetullah Rabia Gülnuş Sultan Others | ||||

| Issue Among others | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ottoman | ||||

| Father | Ibrahim | ||||

| Mother | Turhan Sultan | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| Tughra |  | ||||

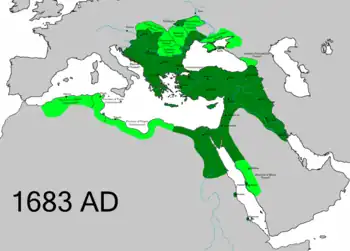

Under Mehmed IV's reign, the empire reached the height of its territorial expansion in Europe. From a young age he developed a keen interest in hunting, for which he is known as avcı (translated as "the Hunter").[1] In 1687, Mehmed was overthrown by soldiers disenchanted by the course of the ongoing War of the Holy League. He subsequently retired to Edirne, where he resided and died of natural causes in 1693.[1]

Early life

Born at Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, in 1642, Mehmed was the son of Sultan Ibrahim (r. 1640–48) by Turhan Sultan, a concubine of Russian origin,[2] and the grandson of Kösem Sultan of Greek origin.[3] Soon after his birth, his father and mother quarrelled, and Ibrahim was so enraged that he tore Mehmed from his mother's arms and flung the infant into a cistern. Mehmed was rescued by the harem servants. However, this left Mehmed with a lifelong scar on his head.[4]

Reign

Accession

Mehmed ascended to the throne in 1648 at the age of six,[nb 1] during a very volatile time for the Ottoman dynasty. On 21 October 1649, Mehmed along with his brothers Suleiman and Ahmed were circumcised.[5]

Kösem Sultan, Mehmed's grandmother and regent, was suspected of supporting the rebels and plotting to poison the sultan and replace him with his younger half-brother, Suleiman. As a result, Mehmed agreed to sign his grandmother's death warrant in September 1651.[6]

The empire faced palace intrigues as well as uprisings in Anatolia, the defeat of the Ottoman navy by the Venetians outside the Dardanelles, and food shortages leading to riots in Constantinople. It was under these circumstances that Mehmed's mother granted Köprülü Mehmed Pasha full executive powers as Grand Vizier. Köprülü took office on 14 September 1656.[7] Mehmed IV presided over the Köprülü era, an exceptionally stable period of Ottoman history. Mehmed is known as Avcı, "the Hunter", as this outdoor exercise took up much of his time.

Wars

Mehmed's reign is notable for a revival of Ottoman fortunes led by the Grand Vizier Köprülü Mehmed and his son Fazıl Ahmed. They regained the Aegean islands from Venice, and Crete, during the Cretan War (1645–1669).[8] They also fought successful campaigns against Transylvania (1660) and Poland (1670–1674). When Mehmed IV accepted the vassalage of Petro Doroshenko, Ottoman rule extended into Podolia and Right-bank Ukraine. This event would lead the Ottomans into the Russo-Turkish War (1676–1681). His next vizier, Köprülü Mehmed's adopted son Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa, led campaigns against Russia, besieging Chyhyryn in 1678 with 70,000 men.[9] He next supported the 1683 Hungarian uprising of Imre Thököly against Austrian rule, marching a vast army through Hungary and besieged Vienna. At the Battle of Vienna on the Kahlenberg Heights, the Ottomans suffered a catastrophic rout by Polish-Lithuanian forces famously led by King John III Sobieski (1674–1696), and his allies, notably the Imperial army.[10]

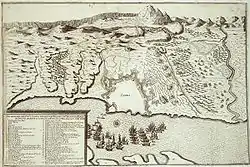

In 1672 and 1673, the sultan, who embarked on two Polish-Lithuanian campaigns with serdar-ı ekrem and Grand Vizier Fazıl Ahmed Pasha, and the acquisition of the Kamaniçi Castle, returned to Edirne after the signing of the Bucaş Treaty.[11]

Fire of 1660

The fire of 4–5 July 1660 was the worst conflagration Constantinople had experienced to that date. It started in Eminönü and spread to most of the historic peninsula, burning much of the city. Even the minarets of Suleiman I's mosque burned. Two-thirds of Istanbul was turned to ash in the conflagration, and as many as forty thousand people were killed. Thousands died in the famine and plague which followed the fire. Following the fire, the dynasty expelled Jews from a wide swath of Istanbul, confiscated their synagogues and homes so that in their place the Yeni Cami (New Mosque) and the Spice Bazaar (Egyptian Market) could be built.

Great Turkish War

On 12 September 1683, the Austrians and their Polish-Lithuanian allies under King John III Sobieski won the Battle of Vienna with a devastating flank attack led by Sobieski's Polish cavalry. The Turks retreated into Hungary; however, this was only the beginning of the Great Turkish War, as the armies of the Holy League began their successful campaign to push the Ottomans back to the Balkans.

Later life and death

In May 1675, Mehmed IV's sons Mustafa II and Ahmed III were circumcised and his daughter Hatice Sultan was married. The empire celebrated it with Famous Edirne Festival to mark the occasion.[11] Silahdar Findikli Mehmed Aga described Mehmed as a medium-sized, stocky, white-skinned, sun-burnt face, with a sparse beard, leaning forward from the waist up because he rides a lot. [12]

1680 witnessed the only known stoning to death of a woman convicted of adultery in Ottoman Istanbul. The unnamed woman was stoned to death on Istanbul's Hippodrome after allegedly being caught alone with a Jewish man, violating Ottoman law which forbade sexual relations between Christian or Jewish men and Muslim women. Mehmed IV witnessed the double execution: he offered the man conversion to Islam so as to avoid being stoned to death (he was beheaded instead).

After the second battle of Mohács (1687), the Ottoman Empire fell into deep crisis. There was a mutiny among the Ottoman troops. The commander and Grand Vizier, Sarı Süleyman Pasha, became frightened that he would be killed by his own troops and fled from his command, first to Belgrade and then to Istanbul. When the news of the defeat and the mutiny arrived in Istanbul in early September, Abaza Siyavuş Pasha was appointed as the commander and soon afterward as the Grand Vizier. However, before he could take over his command, the whole Ottoman Army had disintegrated and the Ottoman household troops (Janissaries and sipahis) started to return to their base in Istanbul under their own lower-rank officers. Sarı Suleiman Pasha was executed, and Sultan Mehmed IV appointed the commander of Istanbul Straits, Köprülü Fazıl Mustafa Pasha, as the Grand Vizier's regent in Istanbul. Fazıl Mustafa made consultations with the leaders of the army that existed and the other leading Ottoman statesmen.

After these, on 8 November 1687, it was decided to depose Sultan Mehmed IV and to enthrone his brother Suleiman II as the new Sultan. Mehmed was deposed by the combined forces of Janissaries and Sekbans commanded by Osman Pasha. Mehmed was then imprisoned in Topkapı Palace. However, he was permitted to leave the Palace from time to time, as he died in Edirne Palace in 1693. He was buried in Turhan Sultan's tomb, near his mother's mosque in Constantinople. In 1691, a couple of years before his death, a plot was discovered in which the senior clerics of the empire planned to reinstate Mehmed on the throne in response to the ill health and imminent death of his successor, Suleiman II.

Mehmed's favourite harem girl was Gülnuş Sultan, a slave girl and later his wife. She was taken prisoner at Rethymno (Turkish Resmo) on the island of Crete. Their two sons, Mustafa II and Ahmed III, became Ottoman Sultans during 1695–1703 and 1703–1730, respectively.

Family

Consorts

Mehmed IV had an Haseki Sultan and several secondary concubines. However, the lack of information about them (except for his Haseki) and the relatively low number of children has created controversy over the actual existence of some of them.

Mehmed IV's known consorts are:[13]

- Emetullah Rabia Gülnuş Sultan. Of Greek origin, her real name was Evmania Voria. She was the first concubine of Mehmed IV and the most beloved, his Haseki and mother of two sultans. She became particularly famous for her many travels, first accompanying the sultan and then her two sons wherever they went. The Yeni Valide mosque was built in her honor by his son Ahmed III.

- Afife Hatun. Also called Afife Kadın, she was Mehmed's second favorite and a poet. During the period of confinement in the Eski Saray after the deposition of Mehmed IV, she wrote verses dedicated to his pain and to that of Gülnuş, who "screamed until she hurt her lungs", while Mehmed, in his room, wept for not being able to console her. Mehmed dedicated some poems to her, also.[14]

- Gülnar Hatun. Also called Gülnar Kadın. Her existence is controversial, with some historians speculating that she may be Gülnuş herself, whose name was misspelled by some.

- Nevruz Hatun. Also known as Nevruz Kadın, she founded a school in the Süleymaniye neighborhood.

- Güneş Hatun. Her existence is controversial, with some historians speculating that she may be Gülnuş herself, whose name was misspelled by some.

- Gülbeyaz Hatun. Mother of a daughter, according to the chronicles she was killed out of jealousy by Gülnuş, who threw her off a cliff, or had her killed by strangulation. Her existence is controversial.

- Hatice Hatun. She was killed by "Güneş Hatun" (Gülnuş herself according to some historians). Her existence is controversial.

- Cihanşah Hatun

- Dürriye Hatun

- Kaniye Hatun

- Rukiye Hatun

- Siyavuş Hatun

- Rabia Hatun. Also called Rabia Kadin. Uncertain existence, she was a poet. Could be a pseudonym of Afife Hatun.

Sons

Mehmed IV had at least four sons:[13]

- Mustafa II (6 February 1664 or 5 June 1664 – 30 December 1703) – with Gülnuş Sultan. 22nd Sultan of the Ottoman Empire

- Ahmed III (31 December 1673 – 1 July 1736) – with Gülnuş Sultan. He was born in Romania, first sultan to be born out of Turkey since the time of Suleiman I. 23rd Sultan of the Ottoman Empire

- Şehzade Bayezid (15 December 1678 – 18 January 1679, buried in Sultan Mustafa I Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia)[14]

- Şehzade Süleyman (13 February 1681 – before 1691)

Daughters

Mehmed IV had at least seven daughters:[13]

- Hatice Sultan (c. 1660 – 5 July 1743),[14][15] – with Gülnuş Sultan,[16] She married twice and she had five sons and a daughter.[17][14]

- Fülane Sultan (1668? – ?). She married Kasım Mustafa Paşah, governor of Edirne, in 1687.

- Ayşe Sultan (c. 1673 – c. 1676) – with Gülnuş Sultan. Nicknamed Küçük Sultan, that means "little princess". At the age of around two years, she was betrothed to Kara Mustafa Paşah, but the baby girl died shortly after and the marriage never took place.

- Ümmügülsüm Sultan (c. 1677 – 9 May 1720) – with Gülnuş Sultan. Also called Ümmi Sultan or Gülsüm Sultan. She was the favorite niece of her uncle Ahmed II, who after the deposition of her father treated her as his daughter, so much so that he kept her at court with him, unlike her sisters. She married once and had three daughters. She was buried in the Yeni Cami Mosque.

- Fatma Emetullah Sultan (c. 1679 – 13 December 1700) – with Gülnuş Sultan.[16] She married twice and she had two daughters.[18][19]

- Fülane Sultan (? – ?) – presumed with Gülbeyaz Hatun

- Gevherhan Sultan (? – ?). Called also Gevher Sultan.

References

Notes

- He is often reported as having been seven years old upon his accession, a result of the Turkish method of calculating age.

Citations

- Börekçi, Günhan (2009). "Mehmed IV". In Ágoston, Gábor; Bruce Masters (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. pp. 370–371.

- Afyoncu; Uğur Demir, Erhan (2015). Turhan Sultan. Istanbul: Yeditepe Yayınevi. p. 27. ISBN 978-605-9787-24-6.

- Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1923. New York: Basic Books. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

- John Freely (1999). Inside the Seraglio. Chapter 9: Three Mad Sultans

- Sakaoğlu 2015, p. 271.

- Zarinebaf, Fariba (2010). Crime and Punishment in Istanbul: 1700–1800. University of California Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0520262218.

- Streusand, Donald E., Islamic Gunpowder Empires: Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 2011), p. 57.

- Faroqhi, Suraiya (2006). The Ottoman Empire and the World Around It. Bloomsbury. p. 22. ISBN 978-0857730237.

- Davies, Brian (2011). Empire and Military Revolution in Eastern Europe: Russia's Turkish Wars in the Eighteenth Century. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4411-6880-1.

- Finkel, Caroline (2006). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1923. Basic Books. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

- Sakaoğlu 2015, p. 266.

- Sakaoğlu 2015, p. 270.

- Mehmed IV, in The Structure of the Ottoman Dynasty; D.A. Alderson

- Silahdar Findiklili Mehmed Agha (2012). ZEYL-İ FEZLEKE (1065–22 Ca. 1106 / 1654–7 Şubat 1695). pp. 530, 752–753, 1095, 1290.

- Sakaoğlu 2008, p. 380.

- Majer, Hans Georg (1992). The Journal of Ottoman Studies XII: The Harem of Mustafa II (1695–1703). p. 441.

- Uluçay 2011, p. 109.

- Uluçay 2011, p. 110.

- Silahdar Findiklili Mehmed Agha (2001). Nusretnâme: Tahlil ve Metin (1106–1133/1695–1721). pp. 135, 458–459, 841.

Sources

- Sakaoğlu, Necdet (2015). Bu Mülkün Sultanları. Alfa Yayıncılık. ISBN 978-6-051-71080-8.

- Sakaoğlu, Necdet (2008). Bu mülkün kadın sultanları: Vâlide sultanlar, hâtunlar, hasekiler, kadınefendiler, sultanefendiler. Oğlak Yayıncılık.

- Uluçay, Mustafa Çağatay (2011). Padişahların kadınları ve kızları. Ankara, Ötüken.

External links

![]() Media related to Mehmed IV at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mehmed IV at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)