Megalagrion nesiotes

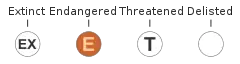

Megalagrion nesiotes is a species of damselfly in the family Coenagrionidae. Its common name is flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly. In the past, the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly lived on the islands of Hawaii and Maui, in the U.S. state of Hawaii. Currently, there is only one population left in east Maui. Limited distribution and small population size make this species especially vulnerable to habitat loss and exotic species invasion. The flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly was last found in 2005.[2] Little is known about this species because of the lack of observation. In 2010, the species was federally listed as an endangered species in the United States.[3]

| Megalagrion nesiotes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Odonata |

| Suborder: | Zygoptera |

| Family: | Coenagrionidae |

| Genus: | Megalagrion |

| Species: | M. nesiotes |

| Binomial name | |

| Megalagrion nesiotes | |

| |

| The island of Maui | |

Description

Adult damselflies have a slender body and fold their wings parallel to the body when at rest. Compared to other damselfly species, the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly is relatively larger and more elongated.[2] Adults are usually 46–50 mm (1.8-1.9 in) in length. Their wingspan reaches 50–53 mm (1.9-2.1 in). Males are blue and black in color. They have enlarged and pincer-like abdominal appendages, cerci. The resemblance of the cerci between this species and the earwigs gives this damselfly its common name. Females are primarily brownish. The wings of both sexes are clear except for the darkened tips.

There are no direct records associated with the immatures of the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly.

Life History

Information about the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly is largely unknown. It is inferred that the life history of this species is like that of some other narrow-winged damselflies in the family Coenagrionidae.[4] As a result, the following life-history traits are from both the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly and other damselfly species in the family Coenagrionidae.

The flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly

The flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly is hemimetabolous. It has three life stages: the egg stage, the immature larval stage (naiad), and the adult stage. Flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly adults are weak flyers. They tend to stay on dense vegetation and fly low near the ground. Females may lay eggs on wet banks or in leaf litter near seeps. No direct observation of the naiads is recorded. However, it is proposed that, unlike many other damselfly species that have fully aquatic naiads, the naiads of the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly are terrestrial or semi-terrestrial.[5] They may live in damp leaf litter or within moist soil or seeps.

General damselfly species in the family Coenagrionidae

Many female damselflies can produce more than one clutch of eggs in their lifetime. They can produce thousands of eggs each time, but the mortality of eggs and naiads is very high. In extreme cases, the survival rate of eggs to adults is only 0-3%.[6]

Damselflies typically reproduce during late spring and summer.[7] They may lay eggs in submerged aquatic plants.[8] It takes about ten days for eggs to hatch. Most naiads of Hawaiian damselfly species are aquatic and predaceous.[9] They have three flattened abdominal gills for breathing, and they feed on small aquatic invertebrates or fish. Naiads may go through 5 to 15 molts as they grow. After several months, they mature and leave the water to become winged adults. For the rest of their life, which usually ranges from a few weeks to several months, they live close to the aquatic habitats and breed there.[10]

Yet, a few other species, including the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly, have terrestrial or semi-terrestrial immatures. These naiads are usually found in moist leafy habitats on the ground.[11][12] They have short and stout and hairy gills and are unable to swim.[13] The knowledge about this kind of naiad is limited and needs more research.

Ecology

Diet

The flying earwig Hawaiian damselflies are assumed to be predaceous.[2] Using the diet of narrow-winged damselflies as a reference, scientists suggest that the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly adults prey on small insects such as flies, mosquitoes, and moths. The immatures have a more aquatic diet including mosquito larvae.[14]

Behavior

The behavior of flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly was not well-observed. According to patterns of other damselfly species, when mating, damselfly males grasp the females with their abdominal appendages, forming in tandem. This behavior helps defend their mates against rival males. When females lay their eggs, the damselfly males guard their habitats.[15] Breeding of the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly takes place in leaf litter or damp banks near streams. There are no direct observations on the naiad biology of this species.

When foraging while flying, the adult damselflies use their spiny legs to form a basket to capture prey. For arthropod prey, they often perch themselves and pounce on their prey.[2]

Flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly adults fly low near their habitats. They are not strong flyers, and they prefer to spend time perching among vegetation.[16] Different from aquatic Hawaiian damselfly species, flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly may fly downward when disturbed. They do not fly up and away like aquatic species.

Habitat

Flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly adults prefer moist areas as habitats. These include wet ridges, forest understory, and steep, fern-covered damp banks. The naiads are believed to live in terrestrial or semi-terrestrial areas, but have never been observed or found. These naiads may occur in leaf litter and plant leaf axils around water, or moist soil between boulders. Flying earwig Hawaiian damselflies are sensitive to temperature changes. They seldom go out on cold and rainy days, while being more active in warm sunny weather.[16][17]

Range

The flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly used to be found on the tropical islands of Hawaii and Maui. However, since the 1930s, this damselfly has not been observed on Hawaii. The last observation of this species was in 2005 on the island of Maui.[2]

Conservation

Population size

There were at least seven populations of this damselfly on the island of Hawaii, and five populations on the island of Maui. Now there is likely only one population left in east Maui. The last observation of the species was in 2005.[18] No quantitative estimate of the size of this remaining population is available.

Past and Current Geographical Distribution

In the past, the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly was on the islands of Hawaii and Maui. In Hawaii, it was known from seven or more general localities. The species has not been seen on Hawaii for over 80 years, however. Surveys within suitable habitats in the Kau and Olaa areas from 1997 to 2008 did not find any of the species.[19] On Maui, the damselfly was historically reported from five general locations on the windward side of the island.[16] Since the 1930s, however, it has only been observed in one area along a stream on the windward side of east Maui.

Major threats

One of the major threats of this damselfly is habitat loss.[4] It is mainly caused by agricultural and urban development. Currently, global climate changes can also impact the habitat of the species. Stream modifications and diversions could change the surrounding flora, fauna, and prey availability. These changes may degrade the habitat as well.

Nonnative animals, particularly feral pigs, are another major threat.[20] Feral pigs in wet forests on Maui crush the forest floor and lie around in moist areas. These activities remove local vegetation.[21][22] Their excrement also provides nutrients to invasive plant species. On Maui, the feral pigs have destroyed the uluhe-dominated riparian habitat.

Finally, the overcollection of individuals, especially breeding adults, threatens the damselfly population.[23]

Listing under the ESA

The flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly was petitioned to be listed under the ESA on May 11, 2004.

On June 24, 2010, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined the endangered status of the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. This indicates that the species will be given federal protections.[24]

5-year review

A 5-year review takes all information available of the species at the time of review. The two latest 5-year reviews of the flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly were conducted in 2016 and 2021.[2] No significant new information was discovered.

Species Status Assessment

No Species Status Assessments (SSA's) are currently available for this species.

Recovery Plan

No final recovery plan for Megalagrion Nesiotes alone is available now.

There is, however, a draft recovery plan for 50 Hawaiian archipelago species.[2] The draft was proposed on February 24, 2022. This document includes the recovery criteria for 3 species of Hawaiian damselflies, including Megalagrion Nesiotes. Megalagrion Nesiotes has a recovery priority number of 5. The goal is to make the species have redundant populations in its historical ranges. Populations should be self-sustaining, resilient, and genetically diverse.

Megalagrion Nesiotes requires systematic surveys and continuous population monitoring. Major strategies include the restoration and protection of species-specific habitats. It is urgent to increase its population size and distribution. Other plans include captive rearing and genetic storage. It is also necessary to control nonnative species. It is important to work with local government and private entities as well.

The downlisting criteria include at least ten stable populations. Suitable habitats for Megalagrion Nesiotes are protected and all significant threats are under control.

The delisting criteria need 10-year surveys. They ask for a significant increase in the size and distribution of the ten populations. Suitable habitats and minimal threats are also required.

References

- Polhemus, D.A. (2020). "Megalagrion nesiotes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T59741A141752695. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T59741A141752695.en. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- "ECOS: Species Profile". ecos.fws.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- "Regulations.gov". www.regulations.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- Polhemus, Dan A. (1996). Hawaiian damselflies : a field identification guide. Adam Asquith, Hawaii Biological Survey. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 0-930897-91-9. OCLC 35655300.

- "Flying earwig Hawaiian damselfly | Xerces Society". xerces.org. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- Anholt, Bradley R. (1994). "Cannibalism and Early Instar Survival in a Larval Damselfly". Oecologia. 99 (1/2): 60–65. Bibcode:1994Oecol..99...60A. doi:10.1007/BF00317083. ISSN 0029-8549. JSTOR 4220730. PMID 28313948. S2CID 21188083.

- Dańko, Maciej J.; Dańko, Aleksandra; Golab, Maria J.; Stoks, Robby; Sniegula, Szymon (2017-09-01). "Latitudinal and age-specific patterns of larval mortality in the damselfly Lestes sponsa: Senescence before maturity?". Experimental Gerontology. 95: 107–115. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2017.05.008. ISSN 0531-5565. PMID 28502774. S2CID 4501289.

- N.L., Evenhuis (2010-05-25). Dating of the "Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Sodety"(1906-1993). Hawaiian Entomological Society. OCLC 651062024.

- Williams, F. X. (1936). "Biological Studies in Hawaiian Water-Loving Insects, Part 1: Coleoptera or Beetles, Part 2: Odonata or Dragonflies". Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society. hdl:10125/15919. ISSN 0073-134X.

- "Damselfly (Zygoptera)". EcoSpark. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- Zimmerman, Elwood C. (1970). "Adaptive Radiation in Hawaii with Special Reference to Insects". Biotropica. 2 (1): 32–38. doi:10.2307/2989786. ISSN 0006-3606. JSTOR 2989786.

- Simon, C. M.; Gagne, W. C.; Howarth, F. G.; Radovsky, F. J. (1984-09-01). "Hawai'i: A Natural Entomological Laboratory". Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America. 30 (3): 9–17. doi:10.1093/besa/30.3.9. ISSN 0013-8754.

- Polhemus, Dan A. (1997). "Phylogenetic Analysis of the Hawaiian Damselfly Genus Megalagrion (Odonata: Coenagrionidae): Implications for Biogeography, Ecology, and Conservation Biology". Pacific Science. hdl:10125/3216. ISSN 0030-8870.

- "Beneficial insects in the garden: #12 Damselflies". aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- Moore, Richard B. (1983-03-01). "Distribution of differentiated tholeiitic basalts on the lower east rift zone of Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii: A possible guide to geothermal exploration". Geology. 11 (3): 136–140. Bibcode:1983Geo....11..136M. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1983)11<136:DODTBO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- Kennedy, Clarence Hamilton (1934-06-01). "Kilauagrion Dinesiotes, a New Species of Dragonfly (Odonata) from Hawaii". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 27 (2): 343–345. doi:10.1093/aesa/27.2.343. ISSN 1938-2901.

- A., Polhemus, Dan (1996). Hawaiian damselflies : a field identification guide. Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 0-930897-91-9. OCLC 918247650.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - MAGNACCA, KARL N.; FOOTE, DAVID; O’GRADY, PATRICK M. (2008-03-17). "A review of the endemic Hawaiian Drosophilidae and their host plants". Zootaxa. 1728 (1): 1. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1728.1.1. ISSN 1175-5334.

- Polhemus, John T.; Polhemus, Dan A. (2008). "Global diversity of true bugs (Heteroptera; Insecta) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia. 595 (1): 379–391. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9033-1. ISSN 0018-8158. S2CID 45657091.

- Erickson, Terrell A. (2006). Hawai'i wetland field guide : an ecological and identification guide to wetlands and wetland plants of the Hawaiian Islands. C. F. Puttock. Honolulu: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. ISBN 978-1-57306-268-8. OCLC 144521389.

- P., Scott, J. Michael. Stone, Charles (1985). Hawai'i's terrestrial ecosystems : preservation and management ; proceedings of a symposium held June 5-6, 1984 at Hawai'i Volenoes National Park. University of Hawaii. OCLC 224065709.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cuddihy, L. W.; Stone, C. P. (1990). Alteration of native Hawaiian vegetation: effects of humans, their activities and introductions.

- Polhemus, John T.; Polhemus, Dan A. (2008), "Global diversity of true bugs (Heteroptera; Insecta) in freshwater", Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment, Developments in Hydrobiology, vol. 198, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 379–391, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8259-7_40, ISBN 978-1-4020-8258-0, retrieved 2022-04-28

- "Megalagrion nesiotes | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-28.