Medulla oblongata

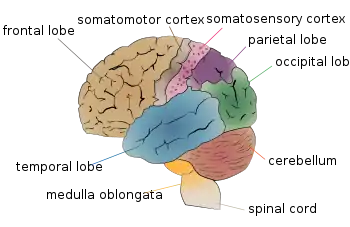

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem.[1] It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (involuntary) functions, ranging from vomiting to sneezing.[2] The medulla contains the cardiac, respiratory, vomiting and vasomotor centers, and therefore deals with the autonomic functions of breathing, heart rate and blood pressure as well as the sleep–wake cycle.[2]

| Medulla oblongata | |

|---|---|

Medulla oblongata purple, part of the brain stem colored | |

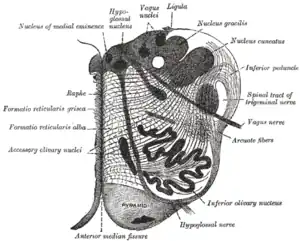

Section of the medulla oblongata at about the middle of the olivary body | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Brain stem |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | medulla oblongata, myelencephalon |

| MeSH | D008526 |

| NeuroNames | 698 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_957 |

| TA98 | A14.1.03.003 |

| TA2 | 5983 |

| FMA | 62004 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

During embryonic development, the medulla oblongata develops from the myelencephalon. The myelencephalon is a secondary vesicle which forms during the maturation of the rhombencephalon, also referred to as the hindbrain.

The bulb is an archaic term for the medulla oblongata.[1] In modern clinical usage, the word bulbar (as in bulbar palsy) is retained for terms that relate to the medulla oblongata, particularly in reference to medical conditions. The word bulbar can refer to the nerves and tracts connected to the medulla, and also by association to those muscles innervated, such as those of the tongue, pharynx and larynx.

Anatomy

The medulla can be thought of as being in two parts:

- an upper open part or superior part where the dorsal surface of the medulla is formed by the fourth ventricle.

- a lower closed part or inferior part where the fourth ventricle has narrowed at the obex in the caudal medulla, and surrounds part of the central canal.

External surfaces

The anterior median fissure contains a fold of pia mater, and extends along the length of the medulla oblongata. It ends at the lower border of the pons in a small triangular area, termed the foramen cecum. On either side of this fissure are raised areas termed the medullary pyramids. The pyramids house the pyramidal tracts–the corticospinal and the corticobulbar tracts of the nervous system. At the caudal part of the medulla these tracts cross over in the decussation of the pyramids obscuring the fissure at this point. Some other fibers that originate from the anterior median fissure above the decussation of the pyramids and run laterally across the surface of the pons are known as the anterior external arcuate fibers.

The region between the anterolateral and posterolateral sulcus in the upper part of the medulla is marked by a pair of swellings known as olivary bodies (also called olives). They are caused by the largest nuclei of the olivary bodies, the inferior olivary nuclei.

The posterior part of the medulla between the posterior median sulcus and the posterolateral sulcus contains tracts that enter it from the posterior funiculus of the spinal cord. These are the gracile fasciculus, lying medially next to the midline, and the cuneate fasciculus, lying laterally. These fasciculi end in rounded elevations known as the gracile and the cuneate tubercles. They are caused by masses of gray matter known as the gracile nucleus and the cuneate nucleus. The soma (cell bodies) in these nuclei are the second-order neurons of the posterior column-medial lemniscus pathway, and their axons, called the internal arcuate fibers or fasciculi, decussate from one side of the medulla to the other to form the medial lemniscus.

Just above the tubercles, the posterior aspect of the medulla is occupied by a triangular fossa, which forms the lower part of the floor of the fourth ventricle. The fossa is bounded on either side by the inferior cerebellar peduncle, which connects the medulla to the cerebellum.

The lower part of the medulla, immediately lateral to the cuneate fasciculus, is marked by another longitudinal elevation known as the tuberculum cinereum. It is caused by an underlying collection of gray matter known as the spinal trigeminal nucleus. The gray matter of this nucleus is covered by a layer of nerve fibers that form the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve. The base of the medulla is defined by the commissural fibers, crossing over from the ipsilateral side in the spinal cord to the contralateral side in the brain stem; below this is the spinal cord.

Blood supply

Blood to the medulla is supplied by a number of arteries.[3]

- Anterior spinal artery: This supplies the whole medial part of the medulla oblongata.

- Posterior inferior cerebellar artery: This is a major branch of the vertebral artery, and supplies the posterolateral part of the medulla, where the main sensory tracts run and synapse. It also supplies part of the cerebellum.

- Direct branches of the vertebral artery: The vertebral artery supplies an area between the anterior spinal and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries, including the solitary nucleus and other sensory nuclei and fibers.

- Posterior spinal artery: This supplies the dorsal column of the closed medulla containing fasciculus gracilis, gracile nucleus, fasciculus cuneatus, and cuneate nucleus.

Development

The medulla oblongata forms in fetal development from the myelencephalon. The final differentiation of the medulla is seen at week 20 gestation.[4]

Neuroblasts from the alar plate of the neural tube at this level will produce the sensory nuclei of the medulla. The basal plate neuroblasts will give rise to the motor nuclei.

- Alar plate neuroblasts give rise to:

- The solitary nucleus, which contains the general visceral afferent fibers for taste, as well as the special visceral afferent column.

- The spinal trigeminal nerve nuclei which contains the general somatic afferent column.

- The cochlear and vestibular nuclei, which contain the special somatic afferent column.

- The inferior olivary nucleus, which relays to the cerebellum.

- The dorsal column nuclei, which contain the gracile and cuneate nuclei.

- Basal plate neuroblasts give rise to:

- The hypoglossal nucleus, which contains general somatic efferent fibers.

- The nucleus ambiguus, which form the special visceral efferent.

- The dorsal nucleus of vagus nerve and the inferior salivatory nucleus, both of which form the general visceral efferent fibers.

Function

The medulla oblongata connects the higher levels of the brain to the spinal cord, and is responsible for several functions of the autonomous nervous system which include:

- The control of ventilation via signals from the carotid and aortic bodies. Respiration is regulated by groups of chemoreceptors. These sensors detect changes in the acidity of the blood; if, for example, the blood becomes too acidic, the medulla oblongata sends electrical signals to intercostal and phrenical muscle tissue to increase their contraction rate and increase oxygenation of the blood. The ventral respiratory group and the dorsal respiratory group are neurons involved in this regulation. The pre-Bötzinger complex is a cluster of interneurons involved in the respiratory function of the medulla.

- Cardiovascular center – sympathetic, parasympathetic nervous system

- Vasomotor center – baroreceptors

- Reflex centers of vomiting, coughing, sneezing and swallowing. These reflexes which include the pharyngeal reflex, the swallowing reflex (also known as the palatal reflex), and the masseter reflex can be termed bulbar reflexes.[5]

Clinical significance

A blood vessel blockage (such as in a stroke) will injure the pyramidal tract, medial lemniscus, and the hypoglossal nucleus. This causes a syndrome called medial medullary syndrome.

Lateral medullary syndrome can be caused by the blockage of either the posterior inferior cerebellar artery or of the vertebral arteries.

Progressive bulbar palsy (PBP) is a disease that attacks the nerves supplying the bulbar muscles. Infantile progressive bulbar palsy is progressive bulbar palsy in children.

Other animals

Both lampreys and hagfish possess a fully developed medulla oblongata.[6][7] Since these are both very similar to early agnathans, it has been suggested that the medulla evolved in these early fish, approximately 505 million years ago.[8] The status of the medulla as part of the primordial reptilian brain is confirmed by its disproportionate size in modern reptiles such as the crocodile, alligator, and monitor lizard.

Additional images

Lobes

Lobes Cross section of the medulla (in red) and surrounding tissues.

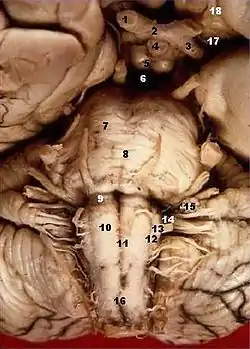

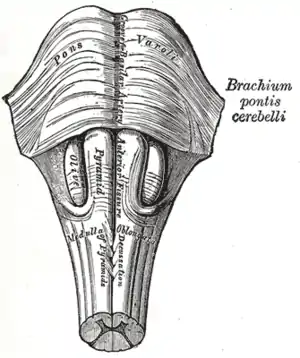

Cross section of the medulla (in red) and surrounding tissues. Anteroinferior view of the medulla oblongata and pons.

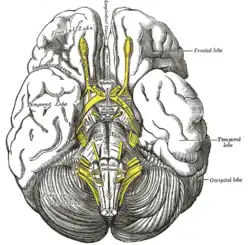

Anteroinferior view of the medulla oblongata and pons. Base of brain.

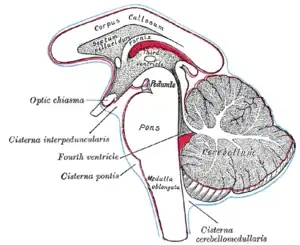

Base of brain. Diagram showing the positions of the three principal subarachnoid cisternæ.

Diagram showing the positions of the three principal subarachnoid cisternæ. Medulla oblongata

Medulla oblongata Micrograph of the posterior portion of the open part of the medulla oblongata, showing the fourth ventricle (top of image) and the nuclei of CN XII (medial) and CN X (lateral). H&E-LFB stain.

Micrograph of the posterior portion of the open part of the medulla oblongata, showing the fourth ventricle (top of image) and the nuclei of CN XII (medial) and CN X (lateral). H&E-LFB stain.

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 767 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 767 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Webb, Wanda G. (2017-01-01), Webb, Wanda G. (ed.), "2 - Organization of the Nervous System I", Neurology for the Speech-Language Pathologist (Sixth Edition), Mosby, pp. 13–43, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-10027-4.00002-6, ISBN 978-0-323-10027-4, retrieved 2020-11-15

- Waldman, Steven D. (2009-01-01), Waldman, Steven D. (ed.), "CHAPTER 120 - The Medulla Oblongata", Pain Review, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, p. 208, doi:10.1016/b978-1-4160-5893-9.00120-9, ISBN 978-1-4160-5893-9, retrieved 2020-11-15

- Purves, Dale (2001). Neuroscience. 2nd edition. Sinauer Associates.

- Carlson, Neil R. Foundations of Behavioral Neuroscience.63-65

- Hughes, T. (2003). "Neurology of swallowing and oral feeding disorders: Assessment and management". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 74 (90003): 48iii–52. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.suppl_3.iii48. PMC 1765635. PMID 12933914.

- Nishizawa H, Kishida R, Kadota T, Goris RC; Kishida, Reiji; Kadota, Tetsuo; Goris, Richard C. (1988). "Somatotopic organization of the primary sensory trigeminal neurons in the hagfish, Eptatretus burgeri". J Comp Neurol. 267 (2): 281–95. doi:10.1002/cne.902670210. PMID 3343402. S2CID 45624479.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rovainen CM (1985). "Respiratory bursts at the midline of the rostral medulla of the lamprey". J Comp Physiol A. 157 (3): 303–9. doi:10.1007/BF00618120. PMID 3837091. S2CID 27654584.

- Haycock, Being and Perceiving

- Haycock DE (2011). Being and Perceiving. Manupod Press. ISBN 978-0-9569621-0-2.