McMahon Line

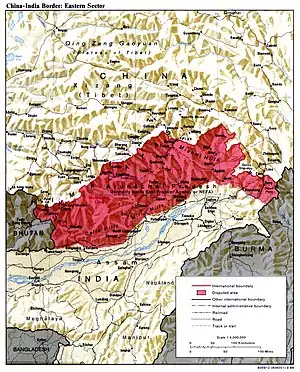

The McMahon Line is the boundary[1] between Tibet and British India as agreed in the maps and notes exchanged by the respective plenipotentiaries on 24–25 March 1914 at Delhi,[2] as part of the 1914 Simla Convention. The line delimited the respective spheres of influence of the two countries in the eastern Himalayan region along northeast India and northern Burma (Myanmar), which were earlier undefined.[3][4][lower-alpha 1] The Republic of China was not a party to the McMahon Line agreement,[6] but the line was part of the overall boundary of Tibet defined in the Simla Convention, initialled by all three parties and later repudiated by the government of China.[7][lower-alpha 2] The Indian part of the Line currently serves as the de facto boundary between China and India, although its legal status is disputed by the People's Republic of China.[12][13] The Burmese part of the Line was renegotiated by the People's Republic of China and Myanmar.

The line is named after Henry McMahon, foreign secretary of British India and the chief British negotiator of the conference at Simla. The bilateral agreement between Tibet and Britain was signed by McMahon on behalf of the British government and Lonchen Shatra on behalf of the Tibetan government.[14] It spans 890 kilometres (550 miles) from the corner of Bhutan to the Isu Razi Pass on the Burma border, largely along the crest of the Himalayas.[15][16]

The outcomes of the Simla Conference remained ambiguous for several decades because China did not sign the overall Convention but the British were hopeful of persuading the Chinese. The Convention and the McMahon's agreement were omitted in the 1928 edition of Aitchison's Treaties.[17] It was revived in 1935 by Olaf Caroe, then deputy foreign secretary of British India, who obtained London's permission to implement it as well as to publish a revised version of Aitchison's 1928 Treaties.[lower-alpha 3]

India regards its interpretation of the McMahon Line as the legal national border, but China rejects the Simla Accord and the McMahon Line, contending that Tibet was not a sovereign state and therefore did not have the power to conclude treaties.[20] Chinese maps show some 65,000 km2 (25,000 sq mi) of the territory south of the line as part of the Tibet Autonomous Region, known as South Tibet in China.[21] Chinese forces briefly occupied this area during the Sino-Indian War of 1962 and later withdrew. China does recognise a Line of Actual Control which closely approximates the McMahon Line in this part of its border with India, according to a 1959 diplomatic note by Prime Minister Zhou Enlai.[22]

The 14th Dalai Lama did not originally recognise India's sovereignty over Arunachal Pradesh. As late as 2003, he said that "Arunachal Pradesh was actually part of Tibet".[23] In January 2007, however, he said that both the Tibetan government and Britain recognized the McMahon Line in 1914. In June 2008, he explicitly recognized for the first time that "Arunachal Pradesh was a part of India under the agreement signed by Tibetan and British representatives".[23]

Background

British India expanded east of Bhutan in the early 19th century with the First Anglo-Burmese War. At the end of the war the Brahmaputra valley of Assam came under its control and over the next few decades British India extended its direct administration over the region in stages. The thickly forested hill tracts surrounding the valley were inhabited by tribal people, who were not easily amenable to British administrative control. The British were content to leave them alone. In 1873, the British drew an "Inner Line" as an administrative line to inhibit their subjects from encroaching into the tribal territory within its control.[25][26] The British boundary, also called the "Outer Line", was defined to mark the limits of British jurisdiction. But it was not significantly different from the Inner Line in this region.[27]

The British wanted peaceful relations with the Himalayan tribes who lived beyond the Outer Line.[28] However, British influence was nevertheless extended to many regions, through treaties, trade relations, and occasional punitive expeditions in response to "outrages" committed against British civilians.[29][30] There is evidence that the British regarded the Assam Himalayan region as a geographical part of India irrespective of political jurisdiction.[31] Guyot-Réchard sees them as having extended "external sovereignty" over the Assam Himalayan tribes.[32]

Forward policies of early 1900s

By 1900, Chinese influence over Tibet had significantly weakened and the British became apprehensive that Tibet would fall into a Russian orbit. In an effort to preclude Russian influence over Tibet and to enforce their treaty rights, the British launched an expedition to Tibet in 1904, which resulted in the Convention of Lhasa between Tibet and Britain.

Qing China became apprehensive about British inroads into Tibet and responded with its own forward policy. They took complete control over the southeastern Kham region of Tibet (also referred to as the "March Country"), through which passed the Chinese communications to Tibet. An assistant amban (imperial resident) was appointed for Chamdo in western Kham to implement the new strategy. Over a period of three years, 1908–1911, the amban Zhao Erfeng implemented brutal policies of subjugation and sinification in the Kham region, for which he earned the nickname of "Zhao the butcher".[33]

Zhao Erfeng's campaigns entered the Tibetan districts adjoining the Assam Himalayan region such as Zayul, Pomed (Bome County) and Pemako (Medog County). They also encroached into parts of the adjoining tribal territory. This alarmed British officials in the region, who advocated the extension of British jurisdiction into the tribal territory.[34][35][36] The higher administration of British India was initially reluctant to concede these demands,[28] but, by 1912, the Army General Staff had proposed drawing a boundary along the crest of Himalayas.[37] The British appear to have been clear that they were only extending the political administration of their rule but not the geographical extent of India, which was taken to include the Assam Himalayan region.[31]

Drawing the line

In 1913, British officials met in Simla, to discuss the status of Tibet.[38] The conference was attended by representatives of Britain, China, and Tibet.[39] "Outer Tibet", covering approximately the same area as the modern "Tibet Autonomous Region", would be administered by the Dalai Lama's government.[39] Suzerainty is an Asian political concept indicating limited authority over a dependent state. The final 3 July 1914 accord lacked any textual boundary delimitations or descriptions.[40] It made reference to a small scale map with very little detail, one that primarily showed lines separating China from "Inner Tibet" and "Inner Tibet" from "Outer Tibet". This map lacked any initials or signatures from the Chinese plenipotentiary Ivan Chen.

Both drafts of this small scale map extend the identical red line symbol between "Inner Tibet" and China further to the southwest, approximating the entire route of the McMahon Line, thus dead ending near Tawang at the Bhutan tripoint. However, neither draft labels "British India" or anything similar in the area that now constitutes Arunachal Pradesh.

The far more detailed McMahon Line map of 24–25 March 1914 was signed only by the Tibetan and British representatives. This map and the McMahon Line negotiations were both without Chinese participation.[41][42] After Beijing repudiated Simla, the British and Tibetan delegates attached a note denying China any privileges under the agreement and signed it as a bilateral accord.[43] British records show that the Tibetan government accepted the new border on condition that China accept the Simla Convention. As Britain did not to get an acceptance from China, Tibetans considered the McMahon line invalid.[6]

British ambiguity (1915–1947)

Simla was initially rejected by the Government of India as incompatible with the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention. C. U. Aitchison's A Collection of Treaties, was published with a note stating that no binding agreement had been reached at Simla.[44] The Anglo-Russian Convention was jointly renounced by Russia and Britain in 1921,[45] but the McMahon Line was forgotten until 1935, when interest was revived by civil service officer Olaf Caroe. The Survey of India published a map showing the McMahon Line as the official boundary in 1937. In 1938, the British published the Simla Accord in Aitchison's Treaties.[44] A volume published earlier was recalled from libraries and replaced with a volume that includes the Simla Accord together with an editor's note stating that Tibet and Britain, but not China, accepted the agreement as binding.[46] The replacement volume has a false 1929 publication date.[44]

In April 1938, a small British force led by Captain G. S. Lightfoot arrived in Tawang and informed the monastery that the district was now Indian territory.[47] The Tibetan government protested and its authority was restored after Lightfoot's brief stay. The district remained in Tibetan hands until 1951. However, Lhasa raised no objection to British activity in other sectors of the McMahon Line. In 1944, the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFT) established direct administrative control for the entire area it was assigned, although Tibet soon regained authority in Tawang.[38]

India–China boundary dispute

When India and Pakistan became independent in 1947 through the partition of India, all the territories that had been part of British India were transferred to the two new countries. The prevailing boundaries of British India were inherited.[48] Maps of the period showed the McMahon Line as the boundary of India in the northeast.

In October 1947, the Tibetan government wrote a note to the Government of India asking for a "return" of the territories that the British had allegedly occupied from Tibet. Among these were listed "Sayul [Zayul] and Walong and in direction of Pemakoe, Lonag, Lopa, Mon, Bhutan, Sikkim, Darjeeling and others on this side of river Ganges". Similar claims were apparently made against China as well. The Indian government did not take the claims seriously and asked instead to be treated on par with the former British Indian government. After a few months, the Tibetans agreed to the proposal.[49][50][51]

In Beijing, the Communist Party came to power in 1949 and declared its intention to "liberate" Tibet. India objected at first, but eventually acquiesced to Chinese claims over Tibet and recognised China as the suzerain power.[38]

In the 1950s, when India-China relations were cordial and the boundary dispute quiet, the Indian government under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru promoted the slogan Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai (Indians and Chinese are brothers). Nehru maintained his 1950 statement that he would not accept negotiations if China brought the boundary dispute up, hoping that "China would accept the fait accompli.[52] In 1954, India renamed the disputed area the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA).

India acknowledged that Tibet was a part of China and gave up its extraterritorial rights in Tibet inherited from the British in a treaty concluded in April 1954.[52] Nehru later claimed that because China did not bring up the border issue at the 1954 conference, the issue was settled. But the only border India had delineated before the conference was the McMahon Line. Several months after the conference, Nehru ordered maps of India published that showed expansive Indian territorial claims as definite boundaries, notably in Aksai Chin.[53] In the NEFA sector, the new maps gave the hill crest as the boundary, although in some places this line is slightly north of the McMahon Line.[22]

The failure of the 1959 Tibetan uprising and the 14th Dalai Lama's arrival in India in March led Indian parliamentarians to censure Nehru for not securing a commitment from China to respect the McMahon Line. Additionally, the Indian press started openly advocating Tibetan independence, with anti-Chinese sentiment steadily rising throughout Indian society due to rising sympathy for the Tibetans. For example, in 1959, Jayaprakash Narayan, one of India's foremost Gandhians, stated that "Tibet may be a theocratic state rather than a secular state and backward economically and socially, but no nation has the right to impose progress, whatever that may mean, upon another nation."[54] Nehru, seeking to quickly assert sovereignty in response, established "as many military posts along the frontier as possible", unannounced and against the advice of his staff.[52] On discovering the posts, and already suspicious from the ruminations of the Indian press, Chinese leaders began to suspect that Nehru had designs on the region. In August 1959, Chinese troops captured a new Indian military outpost at Longju on the Tsari Chu (the main tributary, from the north, of the Subansiri River in Arunachal Pradesh.) Longju was and is just north of the McMahon Line according to the inside back cover map in Maxwell[38] and according to notable Indian mountaineer Harish Kapadia, who explored the area in 2005. His published map and text[55] locate Longju a kilometre or two on the China side of the McMahon Line "near the Chinese garrison town of Migyitun" (which is now quite sizeable, at 28°39'40" N latitude, over four kilometres north of the line). (The rarely reliable coordinates in the Geonames database (National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency) incorrectly place "Longju" in snow and ice 10 kilometres away from the river at over 12,000 feet in elevation.) In a letter to Nehru dated 24 October 1959, Zhou Enlai proposed that India and China each withdraw their forces 20 kilometres from the line of actual control (LAC).[56] Shortly afterwards, Zhou defined this line as "the so-called McMahon Line in the east and the line up to which each side exercises actual control in the west".[22]

In November 1961, Nehru formally adopted the "Forward Policy" of setting up military outposts in disputed areas, including 43 outposts north of Zhou's LAC.[22] On 8 September 1962, a Chinese unit attacked an Indian post at Dhola in the Namka Chu valley immediately south of the Thag La Ridge, seven kilometres north of the McMahon Line according to the map on page 360 of Maxwell.[38] On 20 October China launched a major attack across the McMahon Line as well as another attack further north. The Sino-Indian War which followed was a national humiliation for India, with China quickly advancing 90 km (56 mi) from the McMahon Line to Rupa and then Chaku (65 km southeast of Tawang) in NEFA's extreme western portion, and in the NEFA's extreme eastern tip advancing 30 km (19 mi) to Walong.[57] The Soviet Union,[58] United States, and United Kingdom pledged military aid to India. China then withdrew to the McMahon Line and repatriated the Indian prisoners of war (1963). The legacy of the border remains significant especially in India where the government sought to explain its defeat by blaming it on being caught by surprise.[59]

NEFA was renamed Arunachal Pradesh in 1972—Chinese maps refer to the area as South Tibet. In 1981, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping offered India a "package settlement" of the border issue. Eight rounds of talks followed, but there was no agreement.

In 1984, India Intelligence Bureau personnel in the Tawang region set up an observation post in the Sumdorong Chu Valley just south of the highest hill crest, but three kilometres north of the McMahon Line (the straight line portion extending east from Bhutan for 30 miles). The IB left the area before winter. In 1986, China deployed troops in the valley before an Indian team arrived.[60][22] This information created a national uproar when it was revealed to the Indian public. In October 1986, Deng threatened to "teach India a lesson". The Indian Army airlifted a task force to the valley. The confrontation was defused in May 1987 though, as clearly visible on Google Earth, both armies have remained and recent construction of roads and facilities are visible.[61]

The Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visited China in 1988 and agreed to a joint working group on boundary issues which has made little apparent positive progress. A 1993 Sino-Indian agreement set up a group to define the LAC; this group has likewise made no progress. A 1996 Sino-Indian agreement set up "confidence-building measures" to avoid border clashes. Although there have been frequent incidents where one state has charged the other with incursions, causing tense encounters along the McMahon Line following India's nuclear test in 1998 and continuing to the present, both sides generally attribute these to disagreements of less than a kilometre as to the exact location of the LAC.[61]

Border crossings

Maps

McMahon Line 1914, Map 1

McMahon Line 1914, Map 1 McMahon Line 1914, Map 2

McMahon Line 1914, Map 2 Simla Convention map signed in 1914 (facsimile)

Simla Convention map signed in 1914 (facsimile) Simla Convention map reproduced by Hugh Richardson

Simla Convention map reproduced by Hugh Richardson

Notes

- It is significant that the term "spheres" (of influence) was used. It underscores the fact that the majority of the Assam Himalayan territory was under the control of neither country at that time.[5]

- Whether the Chinese repudiation amounts to a rejection of the McMahon Line is debated by scholars.[8][9][10][11]

- The revised volume of Aitchison's Treaties still carried the original 1929 date, giving rise to allegations of malpractice by later commentators.[18][19]

- In a report to the Government of India in 1903 the Chief Commissioner of Assam, while pointing out the imprecision of the boundary, notes that the boundary and the "outer line" ran along the foot of the hills.[24]

References

Citations

- Lamb, The McMahon Line, Vol. 1 1966, p. 4: "The main British gain from the Simla Conference was the delimitation of the McMahon Line, the boundary along the crest of the Assam Himalayas from Bhutan to Burma, by means of an exchange of Anglo-Tibetan notes."

- Mehra, The McMahon Line and After (1974), p. 230: "To give their agreement shape and form, McMahon and Lonchen exchanged formal letters and copies of maps showing the boundary. This was done at Delhi on 24–25 March."

- Mehra, The McMahon Line and After (1974): Quoting Lord Crew, British Secretary of State for India: "that by a definition of the boundary between Tibet and India he (Crewe) understands the Government of India to mean an agreement as to the spheres, at present undefined, of the two countries in the tribal territory east of Bhutan"

- Mehra, The McMahon Line and After (1974), p. 225: "there was no intention of 'administering' the country 'within the proposed frontier line much less of undertaking 'military operations' in the area in question. And yet,... it was desirable 'to maintain some semblance of authority that could be backed by force, 'if necessary'."

- Lin, Boundary, sovereignty and imagination (2004), p. 26: "As the following discussion reveals, the professed sovereignties claimed by both Republican China and British India over the Assam-Tibetan tribal territory were largely imaginary, existing merely on official maps and political propagandas."

- Shakya, The Dragon in the Land of Snows (1999), p. 279

- Mehra, India–China Border (1982), p. 834: 'The McMahon Line (ML), shown by a Red line on the 1914 map, was an integral part of a longer, more comprehensive line drawn on the convention map to illustrate Article IX thereof... The map is initialled by the three plenipotentiaries 'in token of acceptance" on "this 27th day of April 1914".'

- Lamb, The McMahon Line, Vol. 2 (1966), p. 552.

- Mehra, India–China Border (1982), p. 834.

- Choudhury, The North-East Frontier of India (1978), pp. 154–157.

- Smith, Tibetan Nation (1996), p. 200.

- Claude Arpi (2008). Tibet: The Lost Frontier. Lancer Publishers LLC. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-1-935501-49-7.

- Emmanuel Brunet-Jailly (28 July 2015). Border Disputes: A Global Encyclopedia [3 volumes]: A Global Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 542–. ISBN 978-1-61069-024-9.

- Rao, Veeranki Maheswara (2003). Tribal Women of Arunachal Pradesh: Socio-economic Status. Mittal Publications. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-81-7099-909-6. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- Richardson, Tibet and its History, p. 116.

- "Burma–China Boundary", International Boundary Study, United States Department of State, 1964 – via archive.org: "In negotiating a boundary between British India and Tibet, the line was drawn to include Burma as far east as the Isu Razi pass, south of the Taron River near the Irrawaddy-Salween watershed."

- Mehra, A Forgotten Chapter (1972), pp. 304–305: "for nearly two decades after 1914, the dubious risk of attracting Russian, and later Chinese, attention continued to be the principal reason for the non-publication of the Simla Convention and its adjuncts, the Trade Regulations and the India Tibet boundary agreement."

- Addis, J. M. (April 1963), The India–China Border Question (PDF), Harvard University, p. 27

- Van Eekelen, Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute (2015): "In his Introduction to the Addis Paper Neville Maxwell makes much of this 'dramatic discovery' which in his opinion revealed British diplomatic forgery to induce China/Tibet to cede a broad tract of territory. P. Mehra, p. 419, saw the reason in the sensitivity of the Trade Regulations of 1914 and the policy of 'letting sleeping dogs lie'. Noorani, p. 199, thought the change unnecessary and clumsy as Bell's Tibet Past and Present of 1924 p. 155, had already given the story and map."

- Lamb, The McMahon Line, Vol. 1 (1966)

Grunfeld, The Making of Modern Tibet (1996) - "About South Tibet" (in Chinese). 21cn.com (China Telecom). 18 November 2008. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- Noorani, A. G. (16–29 August 2003), "Perseverance in peace process", Frontline, archived from the original on 28 July 2011

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Tawang is part of India: Dalai Lama". 4 June 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Mehra, The McMahon Line and After 1974, p. 10.

- Banerji, Borders (2007), p. 198: ".. with the growth of commercial interests (mainly tea plantation and Umber), in the second half of the nineteenth century, the British Government became apprehensive of uncontrolled expansion of commercial activities by British merchants, because that could bring them into conflict with the tribal people. To prevent that possibility, the government decided, in 1873, to draw a line—the 'Inner Line'—that could not be crossed without a proper permit."

- Lin, Boundary, sovereignty and imagination (2004), p. 26: "The tribal peoples, notably the Abors, Daflas, Mishmis, Monpas, Akas and Miris, apart from some occasional episodes of subordination to Assam or Tibet, were for all practical purposes independent."

- Lamb, The McMahon Line, Vol. 2 (1966), pp. 313–315: "It [the Outer Line] followed the line of 'the foot of the hills' a few miles to the north of what became the course of the Inner Line."

- Mehra, The McMahon Line and After (1974), p. 11: Quoting Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India, from 1905: "We do not want Mr (J C) White or anybody else to present us with a North-east frontier problem or policy. There being no problem beyond that of remaining on peaceful and friendly terms with our neighbours and quietly developing our relations ... there is no occasion for a policy."

- Banerji, Borders (2007), pp. 198–199: "These British expeditions often came into conflict with the tribal people living in the hill tracts and retaliated with punitive measures.... These punitive expeditions beyond the Outer Line gradually extended British political control to areas that were later to be incorporated into the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA)."

- Lamb, The McMahon Line, Vol. 2 (1966), p. 312: "While the tribal hills were not inside the limits of British territory, yet it was felt that they fell within the sphere of British influence, and that the Indian Government was fully entitled to take what action it saw fit there to protect its interests. There seemed no need, however, before 1910 to have this situation confirmed by any international agreement."

- Van Eekelen, Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute (1967), p. 167: Quoting the Secretary of State for India in 1913, "It should be observed that Tibet is nowhere coterminous with the settled districts of British India, but with a belt of country which, though geographically part of India, politically is partly a no-man's land inhabited by aboriginal savages, partly the territories of states [Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim] ...." (emphasis added)

- Guyot-Réchard, Shadow States (2016), pp. 56–57: "Delhi and London's vision followed an imperial logic: the eastern Himalayas should be a buffer between India and its neighbourhood. Confronted by Chinese expansionism, their aim was limited to achieving external sovereignty over the region – that is, to ensure that no foreign power would intrude into the eastern Himalayas, and that local people would have 'no relations or intercourse with any Foreign Power other than the British Government'."

- Mehra, The McMahon Line and After (1974), Chapter 6. (pp. 67–79).

- Mehra, The McMahon Line and After (1974), Chapter 7.

- Mehra, Britain and Tibet (2016), p. 272: "Mounting Chinese activity in the Assam Himalaya (1907-11) invited reactions in terms of explorations by the British culminating in the Abor expedition (1911), the Mishmi and Miri missions, the Aka and Walong promenades (1911-12) and the Bailey-Moreshead explorations (1913-14) around Tawang."

- Van Eekelen, Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute (1967), p. 167: "When China attempted to reassert control over Tibet around 1910 her troops penetrated into the Walong area and placed boundary markers there. Appreciative of the danger of further encroachment, the governor of Assam in 1910 advised the Viceroy to press forward beyond the limits which "under a self-denying ordinance" contained the frontier."

- Mehra, The McMahon Line and After (1974), pp. 223–225: "All in all, the frontier line proposed by the Army top brass from west to east, was to follow the watersheds of the Subansiri, with its tributaries the Kamala and the Khru, the Dihang as far as its major gorge and all its tributaries south of that point, the Dibang and its confluents and the Lohit and its tributaries. The proposed line, it was pointed out, 'corresponded very closely' with the one suggested by the Government of India in its letter of 1911."

- Maxwell, Neville, India's China War Archived 22 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, New York: Pantheon, 1970.

- "Legal Materials on Tibet – Treaties and Conventions Relating to Tibet – Convention Between Great Britain, China, and Tibet, Simla (1914) [400]". Tibet Justice Center.

- Prescott, J. R. V., Map of Mainland Asia by Treaty, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1975, ISBN 0-522-84083-3, pp. 276–77

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), pp. 144–145

- Maxwell, Neville, India's China War New Delhi: Natraj, pp. 48–49.

- Goldstein 1989, pp. 48–75

- Lin, Boundary, sovereignty and imagination (2004)

- "UK relations with Tibet"

- Schedule of the Simla Convention, 1914 Archived 12 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Goldstein (1991), p. 307.

- Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1969), p. 213.

- Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1969), pp. 213–214.

- Maxwell, India's China War (1970), p. 69.

- Lamb, The McMahon Line, Vol. 2 (1966), p. 580

- Chung, Chien-Peng (2004). Domestic politics, international bargaining and China's territorial disputes. Politics in Asia. Psychology Press. pp. 100–104. ISBN 978-0-415-33366-5.

- Noorani, A. G. (30 September 2003), "Facts of History", Frontline, archived from the original on 13 October 2007

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Garver, John W. (2006). "China's Decision for War with India in 1962" (PDF). In Ross, Robert S. (ed.). New Directions in the Study of China's Foreign Policy. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5363-0. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017.

- "Secrets of Subansiri". The Himalayan Club.

- "Chou's Latest Proposals"

- Maxwell, Neville, India's China War Archived 22 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 408–9, New York, Pantheon, 1970.

- "Soviet Union - India".

- Anand, Dibyesh (2012). "Remembering 1962 Sino-Indian Border War: Politics of Memory". Journal of Defence Studies. 6, 4.

- Sultan Shahin, "Vajpayee claps with one hand on border dispute", Asia Times Online, 1 August 2003

- Natarajan, V. (November–December 2000). "The Sumdorong Chu Incident". Archived 18 January 2013 at archive.today. Bharat Rakshak Monitor 3 (3)

Sources

- Banerji, Arun Kumar (2007), "Borders", in Jayanta Kumar Ray (ed.), Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World, Pearson Education India, pp. 173–256, ISBN 978-81-317-0834-7

- Choudhury, Deba Prosad (1978), The North-East Frontier of India, 1865-1914, Asiatic Society – via archive.org

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1991), A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-91176-5

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1997), The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-21951-9

- Grunfeld, A. Tom (1996), The Making of Modern Tibet (Revised ed.), M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-0-7656-3455-9

- Guyot-Réchard, Bérénice (2016), Shadow States: India, China and the Himalayas, 1910–1962, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-17679-9

- Lamb, Alastair (1964), The China-India border, Oxford University Press

- Lamb, Alastair (1966), The McMahon Line: A Study in the Relations Between, India, China and Tibet, 1904 to 1914, Vol. 1: Morley, Minto and Non-Interference in Tibet, Routledge & K. Paul – via archive.org

- Lamb, Alastair (1966), The McMahon Line: a Study in the Relations Between, India, China and Tibet, 1904 to 1914, Vol. 2: Hardinge, McMahon and the Simla Conference, Routledge & K. Paul – via archive.org

- Lin, Hsiao-Ting (2004), "Boundary, sovereignty, and imagination: Reconsidering the frontier disputes between British India and Republican China, 1914–47", The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 32 (3): 25–47, doi:10.1080/0308653042000279650, S2CID 159560382

- Mehra, Parshotam (February 1972), "A Forgotten Chapter in the History of the Northeast Frontier: 1914-36", The Journal of Asian Studies, 31 (2): 299–308, doi:10.2307/2052598, JSTOR 2052598, S2CID 163657025

- Maxwell, Neville (1970), India's China War, Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0-394-47051-1 – via archive.org

- Mehra, Parshotam (1974), The McMahon Line and After: A Study of the Triangular Contest on India's North-eastern Frontier Between Britain, China and Tibet, 1904-47, Macmillan, ISBN 9780333157374 – via archive.org

- Mehra, Parshotam (15 May 1982), "India-China Border: A Review and Critique", Economic and Political Weekly, 17 (20): 834–838, JSTOR 4370923

- Mehra, Parshotam (2016). "Britain and Tibet: From the Eighteenth Century to the Transfer of Power". Indian Historical Review. 34 (1): 270–282. doi:10.1177/037698360703400111. S2CID 141011277.

- Richardson, Hugh E. (1984), Tibet and its History (Second ed.), Boulder/London: Shambala, ISBN 9780877737896

- Smith, Warren (1996), Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism And Sino-Tibetan Relations, Avalon Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8133-3155-3

- Smith, Warren (2019), Tibetan Nation: A history of Tibetan nationalism and Sino-Tibetan relations, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-00-061228-8

- Shakya, Tsering (1999), The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947, Pimlico, ISBN 978-0-7126-6533-9

- Shakya, Tsering (2012), The Dragon in the Land of Snows: The History of Modern Tibet since 1947, Random House, ISBN 978-1-4481-1429-0

- Van Eekelen, Willem Frederik (1967), Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China, Springer, ISBN 978-94-017-6555-8

- Van Eekelen, Willem (2015), Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China: A New Look at Asian Relationships, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-30431-4

- Woodman, Dorothy (1969), Himalayan Frontiers: A Political Review of British, Chinese, Indian, and Russian Rivalries, Praeger – via archive.org

Further reading

| Library resources about McMahon Line |

- Why China is playing hardball in Arunachal by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, 13 May 2007

- China, India, and the fruits of Nehru's folly by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, 6 June 2007

- The British forgery at the heart of India and China’s Tibetan border dispute by Peter Lee

- The Myth of the McMahon Line by Peter Lee