Mauser Model 1889

The Mauser Model 1889 is a bolt-action rifle of Belgian origin. It became known as the 1889 Belgian Mauser, 1891 Argentine Mauser, and 1890 Turkish Mauser.[2]

| Mauser Model 1889 | |

|---|---|

Argentine Mauser 1891 | |

| Type | Bolt-action rifle |

| Place of origin | German Empire Belgium |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1889–1960s |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars | First Melillan campaign War of Canudos(limited)[1] Greco-Turkish War (1897) Spanish–American War Belgian colonial conflicts First Balkan War World War I Greco-Turkish War Turkish War of Independence Chaco War World War II Congo Crisis Cyprus crisis of 1963–64 |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Mauser |

| Designed | 1889 |

| Manufacturer | Fabrique Nationale Loewe Berlin Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken |

| No. built | ~275,000 |

| Variants | Belgian Mauser rifle M1889 Turkish Mauser rifle M1890 Argentinean Mauser rifle M1891 Belgian Mauser cavalry carbine M1889 Belgian Mauser Engineer carbine M1889 Argentinean Mauser cavalry carbine M1891 Argentinean Mauser Engineer carbine M1891 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass |

|

| Length |

|

| Barrel length |

|

| Cartridge | 7.65×53mm Mauser 7.92×57mm Mauser |

| Caliber | 7.65mm |

| Action | Bolt-action |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,100 ft/s (640 m/s) |

| Feed system | 5-round detachable box magazine |

| Sights | Iron sights adjustable to 1,900 m (2,100 yd) |

History

After the Mauser brothers finished work on the Model 71/84 in 1880, the design team set out to create a small caliber repeater that used smokeless powder.[3] Because of setbacks brought on by Wilhelm Mauser's death, they failed to have the design completed by 1882, and the German Rifle Test Commission (German: Gewehr-Prüfungskommission) was formed. The commission preferred to create their own design.[4] Paul Mauser, who was not aware of the commission work until 1888, has managed to sell an improved version of his M1871/84 rifles as M1887 to the Ottoman Empire.

Meanwhile, in the mid-1880s Belgium wanted to adopt a magazine rifle to replace the Albini-Braendlin and Comblain single-shots.[5] In 1886 Manufacture d’Armes de L’État started trials of several mostly foreign designs, of which M1885 Remington–Lee came on top but was considered too complicated to be adopted.[5] Thus they had to run the second round of trials, and now Mannlicher M1886 would be the winner, but on course of it in 1887 the characteristics of Poudre B smokeless powder and revolutionary smallbore 8×50mmR Lebel cartridge became public, so all blackpowder rifles became obsolescent.[5] The next year Belgians tried a smokeless 8 mm cartridge (still with a rim), of which not much details are known;[5] a Mannlicher rifle in 8 mm with 1887 Belgian proofmarks survived[6] (it may have been a prototype for the Mannlicher M1888). Since every participant needed to work out the kinks of using smokeless powder, the next round of trials didn't continue until November 1888.[5]

Paul Mauser didn't participate in the first two rounds of Belgian trials, but he was developing a rimless cartridge in early 1888, and as soon as he was aware of the Kommissionsgewehr rifle, he started developing a new one.[7] He patented a bolt design somewhat similar to Lee action in February 1888 and a detachable magazine in April and sent a test rifle now known as "Mauser-Metford" to Great Britain, which was also adopting a smallbore cartridge (.303 Rubin, yet to become .303 British) and rifle at the time, but to no avail the (Lee-Metford was adopted instead).[8][7] The same design was sent to the third round of Belgian trials in 7.65 mm, one source states it to be rimmed[5] and another to be modern 7.65x53 mm.[7] On them a faulty cartridge reportedly ruptured, damaging the bolt face and the extractor.[7]

Then there was the last round of trials in summer of 1889, for which Mauser added charging with stripper clips to the rifle: the idea was not unknown and in fact a similar design was patented by a US inventor in 1878, but it was Mauser who commercialized the idea.[9] Mauser won over the Mannlicher-derived design and a Nagant, and the rifle was adopted on October 23, 1889, with some changes to the form of the safety, tweaks to the sights, and lengthening the barrel.[5]

A main feature was the introduction of Mausers newly developed at that time high-performance smokeless powder rimless bottlenecked rifle 7.65×53mm Mauser cartridge.[10] Another new main feature was the ability to load the single-stack detachable box magazine that extended below the bottom of the stock with individual 7.65×53mm Mauser rounds by pushing the cartridges into the receiver top opening or via stripper clips. Each stripper clip can hold 5 rounds to fill the magazine and is inserted into clip guides machined into the rear receiver bridge. After loading, the empty clip is ejected when the bolt is closed. This was a significant improvement for the increase in rate of fire.[11] As a result of opening up the receiver top for more practical stripper clip reloading compared to the transitional design, Mauser chose to move the locking lugs to the front of the bolt (like on the Komissionsgewehr) in order to prevent it from compressing with firing, and the receiver from stretching even the despite the added cost in manufacturing.[5] The forward receiver ring diameter were the two forward locking lugs achieved lockup is 33 millimetres (1.30 in).

Mauser 1889

To compete for Belgian trials, several Belgian arms manufacturers funded the Fabrique Nationale d'Armes de Guerre, now known as FN Herstal.

FN's factory was overrun during World War I, so they outsourced production to a facility in Birmingham, England originally set up by the well known gunmaking firm, W. W. Greener and subsequently handed over to the Belgian Government later in the war, and Hopkins & Allen in the United States.[12] Many Belgian Model 1889 rifles were captured by the Imperial German Army and some were modified to fire the 7.92×57mm Mauser cartridge.[13] Paraguay purchased 7,000 Belgian Model 1889s in 1930.[14]

Rifles captured by Nazi Germany after 1940 were designated Gewehr 261 (b) (Mle 1889 rifle), Karabiner 451 (b) (Mle 1889 carbines), Karabiner 453 (b) (Mle 1916 carbine) and Gewehr 263 (b) (Mle 1889/36).[15] Models 1889/36 were used by German second-line troops or pro-German organisations such as the Vlaamse Wacht.[16] Some Model 1889/36 rifles were still in service in Belgian Congo at the time of the independence of the Republic of the Congo-Léopoldville in 1960 and were used during the Congo Crisis.[17]

Belgian variants

- Model 1889 Carbine with bayonet - with a standard bayonet[18][19]

- Model 1889 Carbine with Yatagan - with a yatagan-like bayonet, used by the Foot Gendarmerie and fortress artillery[19]

- Model 1889 Carbine with bayonet - shorter variant, reconditioned during World War I, using the Gras bayonet[20][19]

- Model 1889 Carbine with bayonet - shorter variant, with a long bayonet and heavier stock, used by the Mounted Gendarmerie[20][21]

- Model 1916 Carbine - slightly modified Mle 1889 with Yatagan, to replace all the earlier models of carbines[22]

- Model 1889/36 Short Rifle or Model 1936, a modernized Model 1889 or Turkish Model 1890 with its bolt modified to cock on opening and the barrel, barrel bands, front handguard and sights of the Mauser Model 1935[16][23][24]

Mauser 1890

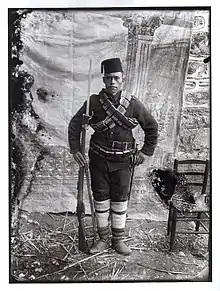

The Belgians talks with Mauser prompted the Ottoman Empire, whose contract for Model 1887 rifles included an "escape clause" allowing them to alter their order to account for any new advancements the Mauser brothers made, to consider the design. In the end they ordered 280,000 pieces of an improved version of the 89 Mauser known as the Turkish Model 1890 rifle.[25] It used a slightly modified 7.65 round.[26] A Model 1890 carbine was also supplied in smaller numbers.[27] These rifles saw service during the First Balkan War[28] and World War I. Large numbers of these rifles were captured by the British Army during World War I and sent to supply the Belgian Army.[20] Mauser 1890 rifles were fielded by both Nationalist[29] and Sultanate armies during the Turkish War of Independence.[30] Some of these rifles were captured by Kurdish[31] and Circassian rebels.[32] In the 1950s, these rifles were still kept in reserve[33] but many of them were rebuilt and rechambered in 7.92×57mm during the 1930s.[34] During the Cyprus crisis of 1963–64, old Mauser 1890 rifles were used by Turkish Cypriots.[35]

The Royal Yugoslav Army received Turkish Mausers as war reparation. Some were used unmodified as Puska M90 T and others shortened as Puska M 03 T.[36] Some of these rifles were captured by the Nazi Germany and designated Gewehr 297 (j).[37]

Mauser 1891

While this was taking place, the Argentine Small Arms Commission contacted Mauser in 1886 to replace their Remington Rolling Block rifles. 180,000 rifles and 30,000 carbines, all chambered in 7.65×53mm Mauser, were ordered. As with other early Mausers, the arms, designated Mauser Modelo 1891, were made by the Ludwig Loewe company and the Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken.[38] M1891 carbines were still in service with the Argentine Police in the 1960s.[39]

Bolivia bought 15,000 Argentine-made Modelo 1891s in the period between 1897 and 1901,[40] they were designated Modelo 1895 (not to be confused with the Mauser Model 1895).[41] They saw combat during the Chaco War.[42] Argentine-made M1891s were also purchased by Colombia[43] and Ecuador.[44]

Peru bought an identical rifle from Ludwig Loewe & Co factory, the Peruvian Model 1891.[45] Several thousands were bought.[46]

Spain bought some 1,200 Mauser 1891 rifles and carbines in 7.65×53mm Mauser for trials. Eventually, the Kingdom adopted the Mauser Model 1893, firing the 7×57mm Mauser cartridge.[47] In 1893, Spain bought several thousands of Modelo 1891 rifles and carbines from Argentina to quell the Melilla revolt in the Moroccan Rif. Later shipped to Cuba, the guns were captured in 1898 by the American forces at the end of the Spanish–American War.[48]

Features

One of the principal defining features of the Belgian Mauser was its thin sheet steel jacket surrounding the barrel—a rather unusual element not common to any other Mauser mark of note.[49] The jacket was instituted as a feature intended to maintain the effectiveness of the barrel and the solid wooden body over time, otherwise lengthening its service life and long-term accuracy when exposed to excessive firing and battlefield abuse. In spite of this approach, the jacketed barrel proved susceptible to moisture build-up and, therefore, introduced the problem of rust forming on the barrel itself–unbeknown to the user. In addition, the jacket was not perforated in any such way as to relieve the barrel of any heat build-up and consequently proved prone to denting. As such, barrel quality was affected over time regardless of the protective measure. Furthermore, another design flaw of the jacket was its extra steel content. Not only was it expensive but it was also needed in huge quantities to provide for tens of thousands of soldiers. By many accounts, the barrel jacket was not appreciated by its operators who depended on a perfect rifle in conflict. Another defining characteristic, unlike most Mausers until then, was a cock-on-closing bolt action resembling that of the British Lee-Metford, which predates the Mauser 1889 by five years. This development allowed for faster firing and was well received.

The Model 1889 featured a single-piece solid wooden body running the entire weapon, ending just aft of the muzzle. It contained two bands and iron sights were fitted at the middle of the receiver top and at the muzzle like virtually all other rifles of the time. Overall length of the rifle was just over 50 inches (1,300 millimeters) with the barrel contributing to approximately 30 inches (760 millimeters) of this length.[50] Of course, a fixed bayonet was issued and added another 10 inches (250 millimeters) to the design as doctrine of the period still relied heavily on the bayonet charge for the defensive victory.

All variations used the same 7.65mm round-nosed cartridge. Many parts were interchangeable, with the exception of the bayonets of the 89 and 90/91; the barrel shroud made the bayonet ring too wide.

Users

References

- "ArmasBrasil - Carabina Mauser Belga".

- "Mauser model 98 (Germany) / 1889 Belgian Mauser, 1891 Argentine Mauser, 1890 Turkish Mauser". 27 July 2012.

- Smith 1954, p. 70.

- Smith 1954, p. 77.

- "Small Arms of WWI Primer 086: Belgian Mauser 1889 – Surplused". October 23, 2018.

- "0 sans titre".

- Speed, Jon. "Mauser Revelation" (PDF). Man Magnum (April 2020): 36–40. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- https://collections.royalarmouries.org/object/rac-object-276074.html

- "Five Supposed Mauser Firsts ... That Weren't -". April 13, 2017.

- "Wilhelm and Peter Paul Mauser: History of the Mauser Brothers".

- Smith 1954, p. 88.

- Vanderlinden, Anthony (2015). "The Belgian Model 1889 Mauser". American Rifleman. National Rifle Association of America. 163 (February): 73–76 & 103.

- Ball 2011, pp. 23–24.

- Ball 2011, p. 273.

- Ball 2011, pp. 422–424.

- Guillou, Luc; Denamur, Patrick (January 2012). "Les fusils Mauser Belges modèle 1935 et 1936". Gazette des armes (in French). No. 38. pp. 36–41.

- "WWII weapons with Force Publique in the Belgian Congo". wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com. 29 June 2015.

- Ball 2011, p. 29.

- Smith 1969, p. 218.

- Ball 2011, p. 34.

- Smith 1969, p. 219.

- Ball 2011, p. 35.

- Ball 2011, p. 36.

- "Nouvelle page 0".

- Ball 2011, p. 377.

- Smith 1954, p. 100.

- Ball 2011, p. 379.

- Ball 2011, p. 378.

- Athanassiou 2017, p. 46.

- Athanassiou 2017, p. 45.

- Athanassiou 2017, p. 47.

- Athanassiou 2017, p. 44.

- Smith 1954, p. 101.

- Ball 2011, p. 388.

- Bloomfield, Lincoln P.; Leiss, Amelia Catherine; Legere, Laurence J.; Barringer, Richard E.; Fisher, R. Lucas; Hoagland, John H.; Fraser, Janet; Ramers, Robert K (30 June 1967). The Control of local conflict : a design study on arms control and limited war in the developing areas. Vol. 2. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Center for International Studies. p. 149. hdl:1721.1/85055.

- Ball 2011, pp. 320–321.

- Ball 2011, p. 427.

- Ball 2011, pp. 9–12.

- Smith 1969, pp. 194–195.

- "boliviapage1". carbinesforcollectors.com. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- Ball 2011, p. 57.

- Huon, Jean (September 2013). "The Chaco War". Small Arms Review. Vol. 17, no. 3.

- Ball 2011, p. 100.

- Ball 2011, p. 127.

- Ball 2011, pp. 287–288.

- Guillou, Luc (December 2006). Le fusil Mauser peruvien modèle 1909. pp. 22–25.

{{cite book}}:|magazine=ignored (help) - Ball 2011, pp. 335–338.

- Ball 2011, p. 436.

- Ball 2011, p. 22.

- Ball 2011, p. 24.

- "Fuzís Mauser no Brasil e as Espingardas da Fábrica de Itajubá (Rev. 2". 5 April 2011.

Bibliography

- Athanassiou, Phoebus (30 Nov 2017). Armies of the Greek-Italian War 1940–41. Men-at-Arms 514. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472819178.

- Ball, Robert W. D. (2011). Mauser Military Rifles of the World. Iola: Gun Digest Books. ISBN 9781440228926.

- Smith, Joseph E. (1969). Small Arms of the World (11 ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Stackpole Company. ISBN 9780811715669.

- Smith, W.H.B. (1954). Mauser Rifles and Pistols (4 ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Stackpole Company.

- Vanderlinden, Anthony (2016). FN Mauser Rifles - Arming Belgium and the World. Wet Dog Publications. ISBN 978-0-9981397-0-8.

- Webster, Colin (2003). Argentine Mauser Rifles 1871-1959. ISBN 0-7643-1868-3.