Marmon Motor Car Company

| |

| Industry | Automobile |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1902 |

| Defunct | 1933 |

| Fate | Renamed |

| Successor | Marmon-Herrington |

| Headquarters | Indianapolis, Indiana, United States |

Key people | Howard Carpenter Marmon, Ray Harroun, Owen Nacker, James Bohannon |

| Products | Vehicles, parts |

Marmon Motor Car Company was an American automobile manufacturer founded by Howard Carpenter Marmon and owned by Nordyke Marmon & Company of Indianapolis, Indiana, US. It produced luxury automobiles from 1902 to 1933.

It was established in 1902 but not incorporated as the successor of Nordyke Mormon & Company until 1926. In 1933 it was succeeded by Marmon-Herrington and in 1964 the Marmon brand name was sold to the Marmon Motor Company of Denton, Texas. Marmon-Herrington became the Marmon Group of Chicago, in 1964.

Marmon Automobiles

Marmon's parent company was founded in 1851, manufacturing flour grinding mill equipment and branching out into other machinery through the late 19th century. Small limited production of experimental automobiles began in 1902, with an air-cooled V-twin engine. An air-cooled V4 followed the next year, with pioneering V6 and V8 engines tried over the next few years, before more conventional straight engine designs were settled upon. Marmons soon gained a reputation as reliable, speedy upscale cars.

Model 32

The Model 32 of 1909 spawned the Wasp. The Wasp, driven by Marmon engineer Ray Harroun (a former racer who came out of retirement for just one race), was the winner of the first ever Indianapolis 500 motor race, in 1911. This car featured the world's first known automobile rear-view mirror.[1]

Model 48

The 1913 Model 48 was a left-hand steering[2] tourer with a cast aluminum engine[3] and electric headlights and horn, as well as electric courtesy lights for the dash and doors.[3] It used a 573 in3 (9,382 cc) (4½×6-inch, 114×152 mm) T-head straight-six engine of between 48 and 80 hp (36 and 60 kW)[3] with dual-plug ignition[4] and electric starter. It had a 145 in (3683 mm) wheelbase (long for the era) and 36×4½-inch (91×11.4 cm) front/37×5-inch (94×12.7 cm) rear wheels (which interchanged front and rear)[5] and full-elliptic front and ¾-elliptic rear springs. Like most cars of the era, it came complete with a tool kit; in Marmon's case, it offered jack, power tire pump, chassis oiler, tire patch kit, and trouble light. The 48 came in a variety of models: two-, four-, five-, and seven-passenger tourers at US$5,000 ($148,047 in 2022 dollars [6]), seven-passenger limousine at US$6,250 ($185,059 in 2022 dollars [6]), seven-passenger landaulette at US$6,350 ($188,020 in 2022 dollars [6]), and seven-passenger Berlin limousine at US$6,450 ($190,981 in 2022 dollars [6]).

Model 34

The 1916 Model 34 used an aluminum straight-six, and used aluminum in the body and chassis to reduce overall weight to just 3295 lb (1495 kg). A Model 34 was driven coast to coast as a publicity stunt, beating Erwin "Cannonball" Baker's record to much fanfare.

.jpg.webp)

New models were introduced for 1924, replacing the long-lived Model 34, but the company was facing financial trouble, and in 1926 was reorganized as the Marmon Motor Car Co.

Little Marmon, Roosevelt

In 1927 the Little Marmon series was introduced and in 1929, Marmon introduced an under-$1,000 straight-eight car, the Roosevelt, but the stock market crash of 1929 made the company's problems worse.

Marmon Sixteen

Howard Marmon had begun working on the world's first V16 engine in 1927, but was unable to complete the production Sixteen until 1931. By that time, Cadillac had already introduced their V-16, designed by ex-Marmon engineer Owen Nacker. Peerless, too, was developing a V16 with help from an ex-Marmon engineer, James Bohannon.

The Marmon Sixteen was produced for three years. The engine displaced 491 in³ (8.0 L) and produced 200 hp (149 kW). It was an all-aluminum design with steel cylinder liners and a 45° bank angle.[7]

Innovation

Marmon became notable for its various pioneering works in automotive manufacturing; for example, it is credited with having introduced the rear-view mirror, as well as pioneering the V16 engine and the use of aluminum in auto manufacturing. The historic Marmon Wasp race car of the early 20th century was also a pioneering work of automobile engineering, as it was the world's first car to use a single-seater "monoposto" construction layout.

Manufacturing Plant

The original Nordyke & Marmon Plant 1 was at the southwest corner of Kentucky Avenue and West Morris Street. Plant 2 was at the southwest corner of Drover and West York Street. Plant 3 was a five-story structure measuring 80 x 600 feet parallel to Morris Street (now Eli Lilly & Company Building 314). The Marmon assembly plant was built adjacent to the Morris Street property line with Plant 3 behind and parallel to it (also part of the Eli Lilly complex).[8]

Marmon-Herrington

While the Marmon Company discontinued auto production, they continued to manufacture components for other auto manufacturers and manufactured trucks. When the Great Depression drastically reduced the luxury car market, the Marmon Car Company joined forces with Colonel Arthur Herrington, an ex-military engineer involved in the design of all-wheel drive vehicles. The new company was called Marmon-Herrington.

In the early 1960s, Marmon-Herrington was purchased by the Pritzker family and became a member of an association of companies which eventually adopted the name The Marmon Group. In 2007, the Pritzker family sold a major part of the Group to Warren Buffett's firm Berkshire Hathaway.[9]

For the 1993 Indianapolis 500, to commemorate the 40th anniversary of The Marmon Group of companies, Éric Bachelart drove a tribute to the Marmon Wasp, actually a year old Lola with Buick power, which was uncompetitive and failed to qualify. After qualifications ended, the sponsorship was transferred to the car of John Andretti, who was driving for A. J. Foyt Enterprises. Andretti started 23rd and briefly led before eventually finishing tenth.

Notable Marmon drivers

Actor Francis X. Bushman, at the height of his movie fame in the 1910s, owned a custom built purple painted Marmon. Other actors who were owners of Marmons include Wallace Reid, Douglas Fairbanks and Arthur Tracy.

Statesman and national hero of Finland Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim's official car was a Marmon E-75. Much later, the same car was bought by a group of technology students. It is still the representational car of the Aalto University student union after considerable repairs,[8] and the name Marmon, to some extent, is coupled to this specific vehicle.

J. Horace McFarland, president of the American Civic Association, owned a Marmon. In 1924, he wrote to John Gries of the National Bureau of Standards' Division of Building and Housing that his Marmon cost nine cents a mile to operate, "independent of the chauffeur."[10]

Jan Werich and George Voskovec, Czech actors and leading members of Osvobozené divadlo, noted their travels to Nurenberg by Marmon car.

In his memoir, "The Cruise of the Rolling Junk", F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote about a 1,200-mile automobile trip to the South that he and Zelda Fitzgerald took in their used 1918 Marmon Speedster.

In 1916–17, Ruby Archambeau of Portland, Oregon, became the first woman to drive the circumference of the United States. Her vehicle was a Marmon.[11]

"King of Bootleggers" Italian Canadian Rocco Perri of Hamilton, Ontario, was known to favour Marmons in the 1920s.

Actress Bebe Daniels was driving a Marmon Roadster 72 miles per hour south of Santa Ana when she became the first woman to be convicted of speeding in Orange County. [12]

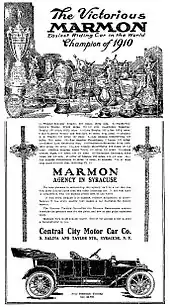

Advertisements

A 1911 Marmon Advertisement - Syracuse Post-Standard, March 18, 1911 |

Marmon "48" from 1914 ad |

References

- "Rearview Mirror". Ward's Auto World. May 1, 2002. Archived from the original on 2005-04-26. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- Clymer, Floyd (1950). Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 115.

- Clymer, p. 115.

- Clymer, p. 115. This would reappear several times in later years, including on the 2.3 liter Ford Ranger pickup.

- Clymer, p. 115. Evidently this was not usual.

- 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- Horvath, Dennis E. "Use of aluminium in autos debuted in 1902". www.autogiftgarage.com. Archived from the original on 2014-06-20.

- "Marmon history". marmon.ayy.fi.

- Bajaj, Vikas (December 26, 2007). "Rapidly, Buffett Secures a Deal for $4.5 Billion". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- McFarland, J. Horace (5 November 1924). Letter to John Gries. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- "Circum-motoring the U.S." Motor Age. 14 September 2018. Retrieved 2021-10-06 – via Google Books.

- "Bebe Daniels: The Orange County "Speed Girl"". Orange County Sheriff's Museum & Education Center. Retrieved 2021-10-06.