Mario Guiducci

Mario Guiducci (18 March 1583 in Florence – 5 November 1646 in Florence) was an Italian scholar and writer. A friend and colleague of Galileo, he collaborated with him on the Discourse on Comets in 1618.

%252C_1650-1700_ca.%252C_lucciola_tra_le_spighe.jpg.webp)

Early life

Mario Guiducci was born in the San Frediano quarter of Florence. His father was Alessandro Guiducci, son of a senator, and his mother was Camilla Capponi. He had at least two brothers, Giulio, who died in 1654 and Simone, as well as a sister, Maddalena, who married Orazio Cavalcanti. He was sent to the Jesuit College in Rome as a boy. He never appears to have earned his doctorate in philosophy at Rome, but he did become a Doctor of both laws at the university of Pisa on 27 May 1610. At some time, probably after this, he became a pupil either of Benedetto Castelli, or, possibly, of Galileo himself.[1]

Disputes about comets, 1618-20

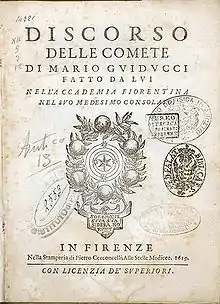

In 1618, the year Guiducci became consul of the Accademia Fiorentina, a particularly bright and long-lasting comet was seen in the skies over Europe, and soon afterwards an anonymous pamphlet was published in Rome entitled "De Tribus Cometis Anni MDCXVIII". The pamphlet argued that comet was a real phenomenon and not an optical illusion or atmospheric effect. The author was the Jesuit Orazio Grassi. There were a number of arguments in this which Galileo wanted to counter, but he decided that it would be wise not to publish his arguments under his own name, so he collaborated with Guiducci to produce a text, Discourse on Comets, which Guiducci read out at the Accademia Fiorentina in May 1619 and published the next month.[2]

The Discourse on comets, although formally a response to Grassi, was fundamentally a rebuttal of the arguments made by Tycho Brahe. It argued that the absence of parallax observable with comets meant that they were not real objects, but atmospheric effects, like rainbows. (In fact the apparent lack of parallax is due immense distance of comets from the earth). Galileo (through Guiducci) also argued against Tycho's case for comets having uniform, circular paths. Instead, he maintained, their paths were straight.[3] As well as attacking Grassi, the Discourse also continued an earlier dispute with Christoph Scheiner about sunspots, belittling the illustrations in Scheiner's book as 'badly coloured and poorly drawn.'[4]

While Guiducci and Galileo were working in the Discourse, a second anonymous Jesuit pamphlet appeared in Milan - Assemblea Celeste Radunata Nuovamente in Parnasso Sopra la Nuova Cometa (sometimes wrongly attributed to Giovanni Rho).[5] This argued for the new model of the universe proposed by Tycho Brahe and against the traditional cosmology of Aristotle. Guiducci and Galileo collaborated on a response to this as well, which set out the arguments for a heliocentric model. The debate continued when, in Perugia later in 1619, Grassi published a reply to the Discourse in La Libra Astronomica ac Philosophica under the pen-name Lotario Sarsi Sigensano.[6] This work dismissed Guiducci as a mere 'copyist' for Galileo, and attacked Galileo's ideas directly. While the Accademia dei Lincei were considering what tone a reply from Galileo ought to take, Guiducci replied directly to Grassi in the Spring of 1620. The reply was formally addressed to another Jesuit, Father Tarquinio Galluzzi, his old rhetoric master. Guiducci countered the various arguments Grassi had put forward against Galileo, describing some of Grassi's experiments as 'full of errors and not without a hint of fraud.' Guiducci concluded with an attempt to reconcile experimental evidence with theological arguments, but firmly asserted the primacy of data gathered through observation. Galileo was very pleased with Guiducci's efforts, proposing him for membership of the Accademia dei Lincei in May 1621 (although he did not actually become a member until 1625).[7]

In public, Galileo insisted that Guiducci, and not he, was the author of the Discourse on Comets. In 1623, in the opening section of Il Saggiatore (The Assayer) he complained:

'One might have thought that Sig. Mario Guiducci would be allowed to lecture in his Academy, carrying out the duties of his office there, and even to publish his Discourse on Comets without "Lothario Sarsi" a person never heard of before, jumping upon me for this. Why has he considered me the author of this Discourse without showing any respect for that fine man who was? I had no part in it beyond the honor and regard shown me by Guiducci in concurring with the opinions I had expressed in discussions with him and other gentlemen. And even if the entire Discourse were the work of my pen - a thing that would never enter the mind of anyone who knows Guiducci - what kind of behavior is this for Sarsi to unmask me and reveal my face so zealously? Should I not have been showing a wish to remain incognito?'[8]

Despite Galileo's public protestations, there is no doubt whatever that he was the main author of the Discourse on Comets. The manuscript is largely in Galileo's handwriting, and the sections in Guiducci's hand have been revised and corrected by Galileo.[9]

Sojourn in Rome, 1623-25

In 1623 the Florentine Maffeo Barberini became Pope Urban VIII.[10] He was a friend of many of Guiducci's associates, including Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger. In the autumn of that year Guiducci went to Rome to see if he could gain any preferment under the new Pope, and he regularly frequented the circle of Cardinal Francesco Barberini. In Rome he met Giovanni Faber and, together with the German pamphleteer Gaspar Schoppe, he regularly frequented the house of Virginio Cesarini and had regular contact with member of the Accademia dei Lincei. He also played a valuable role for Galileo, ensuring that he was kept up to date with developments in the Curia and on the reception of his most recent work, The Assayer.[11] In the summer of 1624 he informed Galileo of his meeting with Orazio Grassi and of the apparently positive comments Grassi had made about Copernican theory. Later, he warned Galileo about two strongly-worded attacks from the Jesuit order on those who sought to overthrow the Aristotelian worldview. Guiducci was also the intermediary through whom Galileo communicated to his colleagues in the Accademia dei Lincei the manuscript of his response to Francesco Ingoli's 1616 letter challenging Copernican ideas, De situ et quiete Terrae contra Copernici systema Disputatio.[12] In April 1625 Guiducci warned Galileo in a letter that an accusation had been laid before the Holy Office, accusing The Assayer of Copernicanism,[13][14] which had been declared heretical in 1616.[15] A month later, in May 1625, without having secured any position for himself in Rome, Guiducci returned to Florence.

Activities in Florence

Guiducci took an active part in the cultural life of Florence. As well as being a member of the Accademia Fiorentina, in May 1607 he was admitted to the Accademia della Crusca with the pseudonym 'Ricoverato'.[16] In 1623 he read two discourses on the poetry of Michelangelo to the Accademia Fiorentina, which he had helped to edit, on the occasion of their publication by Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger. He was a member of a third society as well, dedicated to genealogical research, and, also in 1623, he wrote an operetta for it, "La Clave" ("The Nail"), now lost. His involvement with the Accademia di via San Gallo' included the staging of theatrical entertainments and reciting poetry. In 1629 he was busy with the management of a primary school which he founded, organised and promoted.[17]

In the Spring of 1630, during the quarantine imposed on Florence by Grand Duke Ferdinand II to prevent the spread of plague, Guiducci was one of four patricians placed in charge of administering the special provisions in the quarter of Santa Maria Novella. At the end of the same year he composed a panegyric to the Grand Duke for his efforts, which was not printed until some time later, when the danger of the plague had receded and there was no longer a fear that it might be spread by handling printed books. It was finally published in 1634 as Un Panegirico a Ferdinando II Granduca di Toscana per la Liberazione di Firenze dalla Peste.[18]

Hydrology of the Bisenzio River

The business of managing his family's estates prompted Guiducci to become involved in a dispute about the control of the Bisenzio River near Florence in 1630. The river flooded frequently, ruining the land of owners on either side. In September of that year, he was one of 150 landowners who signed a memorial to the Grand Duke asking him to draw up a plan to control the course of the river. An engineer named Bartolotti was commissioned to produce a plan, to which Guiducci and other landowners objected. The dispute became, in part, a disagreement about the physics of flowing water, and whether the Bartolotti project would work as claimed.[19]

Bartolotti's plan was to cut a new, straight course for the river, avoiding the series of bends in its lower course which slowed it down, causing it to burst its banks. However this plan would involve taking land away from owners on the west bank of the river and advantage owners on the east bank. Guiducci and other owners on the west bank appealed against the proposal, arguing that the engineering solution offered would not in fact lead to improved drainage. Instead, they argued, the natural course of the river should simply be dredged, and brush cleared from the banks. Part of Guiducci's argument was that Bartolotti did not understand that when a watercourse was divided, its speed was reduced, so allowing water to flow both down the old river course and down the proposed channel would simply mean two slow-moving bodies of water rather than one, threatening an even larger area with flooding than before. He also advanced the view that bends in a river do not slow the water down, so that a straight channel and a river with bends would discharge the same amount of water in a given time, rendering a straight channel useless. To support his case, Guiducci asked Benedetto Castelli to send a copy of his Treatise on the Measurement of Flowing Water to the magistrates who were to resolve the matter. He may also have had a hand in the invitation to Galileo from the Grand Duke to provide expert assistance with the problem.[20][21]

Galileo had just finished the manuscript of the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems and deployed some of the theoretical arguments about acceleration from this text into his opinion on the Bisenzio. He argued that the speed of water flow was determined by the relative elevation, rather than by the length, of the distance it travelled, supporting Guiducci's view that a new cut making a shorter course for the river would be useless. The Bisenzio dispute illustrates 'the solidarity, rather than the science, of Galileo's pupils.'[22] The rival theories about acceleration of water and approaches to engineering were never fully put to the test however,since in June 1631 the dispute as in any case resolved by a compromise proposed by Guiducci; the landowners on both sides agreed to try the more traditional approach of dredging and brush-clearing first, and then to reconsider Bartolotti's engineering scheme if that did not alleviate the flooding sufficiently.[23]

Galileo's Trial

In the early 1630s Guiducci's relationship with Galileo was very close. Their houses were not far apart in Florence, and Guiducci spent a good deal of time with him. Together with Famiano Michelini and Bonaventura Cavalieri, Guiducci helped Galileo prepare his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems for publication. In 1632, when Galileo was required to go to Rome to face the Inquisition, he left Guiducci in charge of his personal affairs, and of forwarding correspondence with his daughter, Sister Maria Celeste. While Galileo was away, Guiducci kept all of his friends up to date with news from Rome. He encouraged others to lobby for Galileo's exoneration, and he himself argued for his release to Cardinal Luigi Capponi.[24]

After Galileo's sentencing to house arrest in 1633, Guiducci continued his literary and genealogical contacts with former members of the Accademia dei Lincei, which had disbanded on Cesi's death in 1630. Little is recorded of his activities in the 1640s. He died in Florence on 5 November 1646 and was buried in the church of Ognissanti.[25]

References

- Federica Favino. "GUIDUCCI, Mario". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani/. Treccani. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- Mario Biagioli, Galileo Courtier:The Practice of Science in the Culture of Absolutism, University of Chicago Press 1993 pp.62-3

- Tofigh Heidarzadeh (23 May 2008). A History of Physical Theories of Comets, From Aristotle to Whipple. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-1-4020-8323-5.

- Eileen Reeves & Albert Van Helden, (translators) On Sunspots, The University of Chicago Press, 2010 p.320

- Giovanni Pizzorusso (2016). "Giovanni Rho". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Treccani. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- Margherita Hack (24 December 2016). "Grassi, Horatio". Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer. p. 841. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9917-7_536. ISBN 978-1-4419-9916-0.

- "Mario Guiducci (Person Full Display)". Database of Italian Academies. British Library. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Stillman Drake. "The Assayer" (PDF). web.stanford.edu. Stanford University. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- William R. Shea; Mariano Artigas (25 September 2003). Galileo in Rome: The Rise and Fall of a Troublesome Genius. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-19-516598-2.

- Al Van Helden (1995). "Pope Urban VIII Maffeo Barberini (1568-1644)". The Galileo Project. Rice University. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- Federica Favino. "GUIDUCCI, Mario". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani/. Treccani. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "Francesco Ingoli". Galileo Portal. Museo Galileo. 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- Jules Speller (2008). Galileo's Inquisition Trial Revisited. Peter Lang. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-3-631-56229-1.

- Mario Biagioli, Galileo Courtier:The Practice of Science in the Culture of Absolutism, The University of Chicago Press, 1993 p.309

- Maurice A. Finocchiaro (29 August 2006). "Texts from The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History, edited and translated by Maurice A. Finocchiaro". West Chester University. West Chester University. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- "Mario Guiducci". Accademia Della Crusca. Accademia Della Crusca. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Federica Favino. "GUIDUCCI, Mario". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani/. Treccani. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- Federica Favino. "GUIDUCCI, Mario". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani/. Treccani. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- Cesare S. Maffioli (2008). "Galileo, Guiducci and the Engineer Bartolotti on the Bisenzio River". academia.edu. Galileana (V). Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Cesare S. Maffioli (2008). "Galileo, Guiducci and the Engineer Bartolotti on the Bisenzio River". academia.edu. Galileana (V). Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Domenico Bertoloni Meli, Thinking with Objects: The Transformation of Mechanics in the Seventeenth Century, JHU Press 2006 p.85

- John L. Heilbron (14 October 2010). Galileo. OUP Oxford. pp. 462–. ISBN 978-0-19-162502-2.

- Cesare S. Maffioli (2008). "Galileo, Guiducci and the Engineer Bartolotti on the Bisenzio River". academia.edu. Galileana (V). Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Federica Favino. "GUIDUCCI, Mario". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani/. Treccani. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- Federica Favino. "GUIDUCCI, Mario". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani/. Treccani. Retrieved 8 August 2017.