Marino Sanuto the Younger

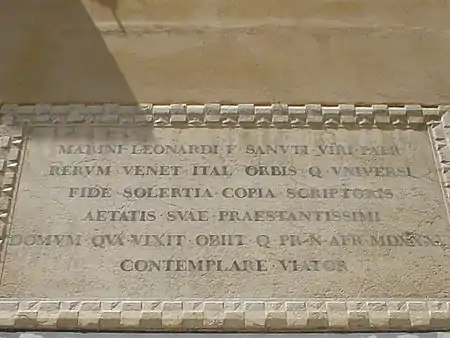

Marin Sanudo, italianised as Marino Sanuto or Sanuto the Younger (May 22, 1466 – 1536), was a Venetian historian and diarist. His most significant work is his Diarii, which he had intended to write up into a history of Venice.[1]

Biography

Early life

He was born into a patrician family of Venice, the son of the senator Leonardo Sanuto. Left an orphan at the age of eight, he lost his fortune owing to the bad management of his elder brother, who eventually left the family for Syria.[2] Thus, Sanuto was for many years hampered by want of means. He spent the rest of his childhood under the protection of his uncle, Francesco Sanuto, who may have also supported him financially.[2]

Sanuto began writing early. Aged fifteen, he wrote the Memorabilia Deorum Dearumque, on the antique gods and goddesses.[2] In 1483 he accompanied his cousin Mario, who was one of the three sindici inquisitori deputed to hear appeals from the decisions of the rettori, on a tour through Istria and the mainland provinces, and he wrote a minute account of his experiences in his diary. Wherever he went he sought out learned men, examined libraries, and copied inscriptions. The result of this journey was the publication of his Itinerario per la terraferma veneziana and a collection of Latin inscriptions.

Adulthood

Sanuto was elected a member of the Maggior Consiglio when only twenty years old (the legal age was twenty-five) and he became a senator in 1498; he noted down everything that was said and done in those assemblies and obtained permission to examine the secret archives of the state.

He collected a fine library, which was especially rich in manuscripts and chronicles both Venetian and foreign, including the famous Altino Chronicle, a collection of legends about early Venetian history which served as a foundation of Venetian historiography, and became the friend of all the learned men of the day, Aldo Manuzio dedicating to him his editions of the works of Angelo Poliziano and of the poems of Ovid. It was a great grief to Sanuto when Andrea Navagero was appointed the official historian to continue the history of the republic from the point where Marco Antonio Sabellico left off, and a still greater mortification when, Navagero having died in 1529 without executing his task, Pietro Bembo was appointed to succeed him. Finally in 1531 the value of his work was recognized by the senate, which granted him a pension of 150 gold ducats per annum. He died in 1536.

Sanuto played a role in placing the Venetian Jews in the first ever Jewish ghetto, as he stated in a speech in 1515, a year before the ghetto's establishment:

"I do not want to omit to relate an evil practice resulting with the continuing contact with these Jews, who reside in great numbers in the cities. Formerly, they were not seen outside their houses from palm Sunday until after Easter. Now till yesterday they were going about and it is a very bad thing, and no one says anything to them, since we need them due to the wars and therefore do what they want."

Works

His chief works are the following:

- Itinerario per la terraferma veneziana, published by M. Rawdon Brown in 1847

- I commentari delta guerra di Ferrara, an account of the war between the Venetians and Ercole I d' Este, published in Venice in 1829

- La Spedizione di Carlo VIII.(MS. in the Louvre)

- Le Vite dei Dogi, published in vol. xxii. of Muratori's Rerum Italicarum Scriptores (1733)

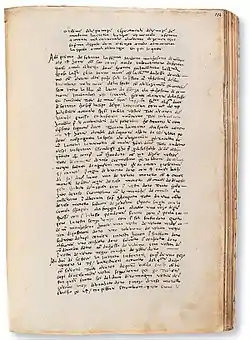

- Diarii, his most important work, which covers the period from 1 January 1496 to June 1533, and fills 58 volumes.[1] The publication of these records was begun by Rinaldo Fulin in 1879, in collaboration with Federigo Stefani, Guglielmo Berchet, and Niccolò Barozzi; the last volume was published in Venice in 1903. Owing to the relations of the Venetian republic with the whole of Europe and the East it is practically a universal chronicle. It is considered an invaluable source of information on that period.[2]

Personal life

He was briefly married to Cecilia Priuli, but the marriage had no issue. He died with no legitimate male heirs, leaving only two illegitimate daughters.[2]

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sanuto, Marino, the younger". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 197.

External links

Venetian Wikisource has original text related to this article: Marin Sanudo

Venetian Wikisource has original text related to this article: Marin Sanudo

- Finlay, Robert (1980). Politics in Renaissance Venice. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0813508886. OCLC 5333626.

- Sanudo, Marino (2008). Venice, cità excelentissima : selections from the Renaissance diaries of Marin Sanudo. Labalme, Patricia H., Sanguineti White, Laura. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. xxv–xxx. ISBN 978-0801887659. OCLC 144570948.