Marguerite Louise d'Orléans

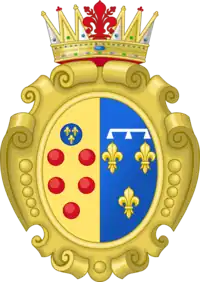

Marguerite Louise d'Orléans (28 July 1645 – 17 September 1721) was a Princess of France who became Grand Duchess of Tuscany, as the wife of Grand Duke Cosimo III de' Medici.

| Marguerite Louise d'Orléans | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait in the Musée de l'Histoire de France | |||||

| Grand Duchess consort of Tuscany | |||||

| Tenure | 23 May 1670 – 17 September 1721 | ||||

| Born | 28 July 1645 Château de Blois, Blois, France | ||||

| Died | 17 September 1721 (aged 76) 15 Place des Vosges, Paris, France | ||||

| Burial | Picpus Cemetery, Paris | ||||

| Spouse | Cosimo III de' Medici | ||||

| Issue Detail | |||||

| |||||

| House | Bourbon | ||||

| Father | Gaston, Duke of Orléans | ||||

| Mother | Marguerite of Lorraine | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

Libertine and unruly in conduct from an early age, her relations with her husband and his family were tempestuous and often bitter, with repeated appeals for mediation to Louis XIV. Nevertheless, three children were born to the couple: Grand Prince Ferdinando, Anna Maria Luisa, Electress Palatine, and Gian Gastone.

In June 1675, five years after her husband had succeeded to the Grand Duchy and four years after the birth of their youngest child, Marguerite Louise and her husband separated and she retired with a pension to a convent on the outskirts of Paris. In France she proved little inclined to respect social conventions governing the life of a woman of her rank and proved a thorn in the side of the Tuscan authorities and the French monarchy, indulgent though it was.

In later life, she eventually adopted more conventional behaviour, took up pious works and even reformed the convent that became her second residence in the Paris suburbs. As the years went by she had serious setbacks to her health and the sadness of mourning her eldest son, Grand Prince Ferdinando, for whom she had had a genuine affection. Rendered financially independent by a legacy, she purchased a house in Paris, from which she spent the end of her life dispensing charity and keeping up dignified correspondence.

Biography

Early life: 1645–1661

Marguerite Louise, the eldest child of Gaston of France, Duke of Orléans, and of his second wife, Marguerite of Lorraine, was born on 28 July 1645[1] at the Château de Blois. She was the eldest of five children born to Gaston by his second wife. Her other sisters included Élisabeth Marguerite, future Duchess of Guise and the Duchess of Savoy.

Marguerite Louise received a rudimentary education at her father's court at Blois, to which he withdrew after the failure of the insurrection against his nephew Louis XIV of France known as the Fronde.[1] Marguerite Louise enjoyed a close relationship with her half-sister, Anne Marie Louise, Duchess of Montpensier, La Grande Mademoiselle, who took her and her friends to the theatre and royal balls; Marguerite Louise returned her sister's affection, attending Anne Marie Louise's salon daily and seeking her guidance in court matters.[2] Marguerite Louise was convinced that Madame de Choisy advised her mother poorly in matters of court and ruined the negotiations for her marriage to Charles Emmanuel II, Duke of Savoy.[3] In the end it had been her own younger sister Françoise Madeleine d'Orléans who married Charles Emmanuel in 1663.[4] It was for this reason that when another proposal came in 1658, this time from Cosimo de' Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany, Marguerite Louise asked her half-sister to bring it about.[5]

Initially overjoyed at the prospect of marrying, Marguerite Louise's ebullience faded to dismay when she discovered her half-sister, despite initially favouring the Tuscan match, then changed her mind.[5] In reaction, Marguerite Louise's behaviour became unconventional: she shocked the court by going out unaccompanied, a grievous offence in contemporary French society, with her cousin Prince Charles of Lorraine, who soon became her lover.[6] Her marriage by proxy, on 19 April 1661, did nothing to change her attitude, much to the annoyance of Louis XIV's ministers. On the day she was supposed to meet diplomats offering their congratulations on the wedding, she attempted instead to go hunting, only to be stopped by the Duchess of Montpensier.[7]

Life in Tuscany: 1661–1670

Grand Princess of Tuscany

.jpg.webp)

Mattias de' Medici, brother to the incumbent Grand Duke's and her bridegroom's uncle, conveyed Marguerite Louise to Tuscany in a fleet comprising nine galleys, three Tuscan, three on loan from the Republic of Genoa and another three from the Papal States. Against all protocol, Charles of Lorraine saw her off at Marseille. The party arrived in Tuscany on 12 June, the bride disembarking at Livorno, and, to much pageantry, she made her formal entry into Florence on 20 June.[8] Their wedding celebrations, the most lavish spectacle Florence had hitherto seen, included of a cortège of over three hundred carriages.[9] As a wedding gift, Grand Duke Ferdinando, the bridegroom's father, presented her with a pearl the "size of a small pigeon's egg".[9]

Marguerite Louise and Cosimo greeted each other with indifference, and, according to Sophia, Electress of Hanover, they only slept together once a week.[10] Marguerite Louise, two days after their marriage, demanded possession of the Tuscan crown jewels from Cosimo, who replied that he did not have the authority to give them.[11] The jewels that she did manage to get from Cosimo she tried to smuggle out of Tuscany, only to be stopped by the Grand Duke.[11] Marguerite Louise's indifference, after this incident, turned to hatred, compounded by her continued love for Charles of Lorraine, from whom she was forced to part at Marseilles.[12] On one occasion, she threatened to break a bottle over Cosimo's head if he did not leave her chamber.[9] Her hatred of Cosimo, however, did not prevent their doing their mutual duty by having children: Grand Prince Ferdinando in 1663, Anna Maria Luisa in 1667 and Gian Gastone in 1671.

Marguerite Louise's unconventional behaviour lead to sour relations with the family. She argued with the Grand Duchess Vittoria over precedence, and with Grand Duke Ferdinando over her spending.[13] Her spending habits not only spelled conflict with the Grand Duke, but made her unpopular with the Florentines. This was compounded by her free-spirited conduct, such as having two grooms who frequent her chamber at all hours.[13]

Pleas to Louis XIV

Following Charles of Lorraine's brief visit to Florence, during which he was entertained by the Grand Ducal family in Palazzo Pitti, the Grand Ducal palace, the tone of Marguerite Louise's letters to Charles led the Grand Duke and Cosimo to spy on her.[14] In response, she unsuccessfully appealed to Louis XIV to intervene,[14] but then both Marguerite Louise and the Grand Duke sent entreaties to Louis XIV after her French staff was dismissed, Marguerite Louise complaining of being maltreated, the Grand Duke asking for help in restraining Marguerite Louise's behaviour.[15]

To placate both the Grand Duke and Marguerite Louise, Louis XIV sent the Comte de Saint Mesme. In the conversations that took place, it emerged that Marguerite Louise wanted to return to France, and Mesme sympathised with this, as did much of the French court, so he concluded his visit without finding a solution to the heir's domestic problems, incensing both Ferdinando and Louis XIV.[16][17][18] Now, Marguerite Louise began forcing the issue by humiliating Cosimo on every possible occasion, as when she insisted on employing only French cooks as she claimed the Medici were out to poison her and when she branded Cosimo "a poor groom" in front of the Papal nuncio.[17]

After several more French attempts at conciliation had failed, in September 1664 Marguerite Louise left her apartment in Palazzo Pitti, refusing to return. As a result, Cosimo moved her into Villa di Lappeggi.[17] where she was watched by forty soldiers, and where six courtiers, appointed by Cosimo, had to follow her everywhere because it was feared she would flee to France.[19] The following year, she changed tack, and was reconciled with the Grand Ducal family. That particular reconciliation collapsed, however, after the birth in 1667 of Anna Maria Luisa.[20]

Grand Duchess of Tuscany: 1670–1721

.jpg.webp)

In May 1670, with the death of Grand Duke Ferdinando II, Marguerite Louise became Grand Duchess of Tuscany. The old tradition of admitting the reigning Grand Duke's mother to the Consulta, or Privy Council, was reinstituted at Cosimo III's accession.[21] Loathing Marguerite Louise for her treatment of Cosimo and herself, Vittoria della Rovere, Cosimo III's mother, ensured that Marguerite Louise was denied membership of the Consulta. Being thus effectively excluded from politics, she was left with nothing else to do but supervise the education of her son the Grand Prince Ferdinando.[22][23] The Grand Duchess, furious at her exclusion, fought with Vittoria over precedence and demanded entry to the Consulta.[23] Cosimo III sided with his mother.[23] Presumably yet another reconciliation, however brief, took place in the summer of 1670, of which a sign was the birth of the couple's last child, Gian Gastone on 24 May 1671. However, by early 1671, the fighting between Marguerite Louise and Vittoria became so heated that a contemporary remarked that "the Pitti Palace has become the devil's own abode, and from morn till midnight only the noise of wrangling and abuse can be heard".[24] The birth of Gian Gastone on the first anniversary of his grandfather Ferdinando II's death, gave an occasion for the child to receive the name of his other, maternal grandfather, Gaston, Duke of Orléans, who had died in 1660. He was later to be the last Medici Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Return to France

At the start of 1672, Marguerite Louise wrote to Louis XIV, begging him for medical assistance for what she described as breast cancer.[25] To tend her, Louis XIV sent Alliot le Vieux, the personal physician who had attended his mother Anne of Austria, who had died of the complaint.[24] Alliot, unlike Mesme, did not completely comply with Marguerite Louise's desire to be sent to France on the pretext of illness, declaring that the tumour was "in no wise malignant", though he did recommend thermal waters.[24][26] Frustrated at the failure of her plan, to upset Cosimo Marguerite Louise began flirting with a cook in her household, tickling him and having pillow fights.[27]

In an effort to restore domestic harmony, Cosimo III sent for Madame du Deffand, Marguerite Louise's childhood governess who had sided with the Grand Duke before.[23] However, because of a string of deaths in the Orléans family, the governess arrived with some delay, in December 1672.[28] By then, Marguerite Louise was in the depths of despair, and asked to be allowed visit Villa Poggio a Caiano, a Medici villa, ostensibly for worship at a nearby shrine.[29] Once there, she refused to return, which resulted in a two-year standoff between herself and the Grand Duke, for he would not consent to her return to France, though she begged for this in her parting letter to him.[30] Madame du Deffand's mission having failed, Louis XIV made one final attempt to reconcile the Grand Ducal couple, to no avail.[31] Therefore, all attempts at conciliation having failed, Cosimo capitulated to Marguerite Louise, in a contract signed on 26 December 1674: Marguerite Louise, provided for with a pension of 80,000 livres, was allowed to leave for France, but she had to confine herself to the Abbey of Saint Peter at Montmartre and surrender her rights as a Royal Princess of France.[32] Overjoyed, the Grand Duchess departed for France laden down with the fixtures and furniture of Villa Poggio a Caiano, for, in her own words, she had no intention "of setting forth without her proper wages".[33]

Montmartre

.jpg.webp)

News of Marguerite Louise's departure from Livorno on 12 July 1675 was greeted with "a great displeasure" by the Florentines.[34] The nobility, too, sympathised with her, believing Cosimo was to blame for driving Marguerite Louise away.[34] At Montmartre Marguerite Louise at first patronised charitable works and bore herself with "an air of piety", but she soon reverted to her unconventional ways, wearing heavy rouge and bright yellow periwigs, and embarking on an affair with the Count of Lovigny, and later with two members of the Luxembourg regiment.[35][36] Louis XIV, ignoring the 1674 contract's article banning Marguerite Louise from setting foot outside the convent, admitted the Grand Duchess to court, where she gambled for high stakes.[37]

Because of her "shabby" retinue and short visits, Marguerite Louise garnered the reputation of a Bohemian among the courtiers of Versailles, and, therefore, was compelled to allow "those of insignificant birth" into her circle.[36] The Tuscan envoy, Gondi, issued frequent protests to the French court against Marguerite Louise's behaviour, to no avail.[38] Eventually, the Abbess of Montmartre, Françoise Renée de Lorraine, (1621–1682), when questioned by the King about Marguerite Louise's latest affair with a groom, replied, "A conspiracy of silence is the sole antidote to the depravity and excesses of [Marguerite Louise]". This perhaps is the motivation behind the fact of Marguerite Louise's absence from memoirs of the time.[38]

Back in Florence, Cosimo III scrutinised closely the reports sent by the Tuscan envoy in France regarding on Marguerite Louise's every movement. If he deemed a particular action of hers to be offensive, he wrote to Louis XIV, demanding an explanation.[39] Initially sympathetic to Cosimo, Louis XIV, tiring of his endless stream of protests, said, "Since Cosimo had consented to the retirement of his wife to France, he had virtually relinquished any right to interfere in her conduct".[40] It was this that prompted Cosimo III to give up concerning himself with his wife's behaviour.[41] Marguerite Louise was informed of Cosimo III's ensuing illness by her eldest son, Grand Prince Ferdinando, who had espoused his mother's cause and corresponded with her.[41][42] Certain of her husband's imminent death, Marguerite Louise told the French court that "at the first notice of her detested husband's demise, she would fly to Florence to banish all hypocrites and hypocrisy and establish a new government".[41] This, however, was not to be, and Cosimo III actually outlived her two years.

In 1688, burdened by debts, Marguerite Louise wrote to Cosimo, begging for 20,000 crowns. When Cosimo was not initially forthcoming, she switched her focus to her son the Grand Prince, in the hope he would help her, but he feigned he could not, for fear of upsetting his father.[43] Eventually, Cosimo paid off her debts, and her financial security was assured when she inherited a large sum of money from a relative in 1696.[44][45]

While Marguerite Louise's behaviour was tolerated by the previous Abbess of Montmartre, the new Abbess, Madame d'Harcourt, frequently complained about her to the Grand Duke and the King.[45] In retaliation, Marguerite Louise threatened to kill the Abbess with a hatchet and a pistol, and formed a clique against her.[46] It was in this context that Cosimo III consented, in line with her wishes, to Marguerite Louise's departure for a new convent, at Saint-Mandé on the Eastern outskirts of Paris, on the condition she go out only with the King Louis XIV's explicit permission and be attended by a chamberlain of his choice.[47] Since she would not agree, her pension was suspended, only to be resumed when Louis XIV compelled her to yield.[47]

Saint-Mandé

At Saint-Mandé, the aging Marguerite Louise adopted a more moderate life and busied herself with reforming the convent, which she called a "spiritual brothel". The absentee mother superior, who wore men's clothing, was sent away, while nuns who departed from the rule were removed. In this way, Marguerite Louise's behaviour ceased to be a bone of contention with Florence.[47] Marguerite Louise's health began to decline in 1712, with an attack of apoplexy, which left her with a paralysed left arm and foaming mouth.[48] She soon recovered, only to have another attack the next year; the death of the only one of her three children with whom she had a good relationship, Grand Prince Ferdinando, contributed to the second attack of apoplexy, which briefly paralysed her eyes and made speech difficult.[48] The Regent of France, Philippe d'Orléans, allowed Marguerite Louise to buy a house in Paris at 15 Place des Vosges, where she spent her final years.[48] She corresponded with the Regent's mother, Elizabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate, and gave assiduously to charity.[48] Marguerite Louise d'Orléans, Princess of France and Grand Duchess of Tuscany, died on 17 September 1721, and was buried in the Picpus Cemetery, in Paris.[49][50]

Issue

Cosimo III and Marguerite Louise had three children:

- Ferdinando de' Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany (1663–1713) married Violante Beatrice of Bavaria, no issue;

- Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici, Electress Palatine (1667–1743) married Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine, no issue;

- Gian Gastone de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1671–1737) married Anna Maria Franziska of Saxe-Lauenburg, no issue.

Ancestors

References

Citations

- Acton, p. 54.

- Pitts, p. 159.

- Pitts, pp. 159–160.

- Oresko 2004, p. 20.

- Pitts, p. 160.

- Pitts, p. 161.

- Pitts, p. 162.

- Acton, p. 70.

- Strathern, p. 386.

- Hibbert, p 288.

- Hibbert, p. 289.

- Acton, p 85

- Acton, p. 86.

- Acton, p 87.

- Acton, pp, 88–89.

- Acton, pp. 91–92.

- Acton, p 93.

- Young, p 453.

- Acton, p 94.

- Acton, p 103.

- Acton, p. 113.

- Young, p 460.

- Acton, p. 114.

- Acton, p. 115.

- Hibbert, p. 293.

- Hibbert, pp. 293–294.

- Hibbert, p. 294.

- Acton, p. 119.

- Acton, p. 120.

- Young, pp. 460–461.

- Hibbert, p. 295.

- Acton, p. 135.

- Acton, p. 136.

- Acton, p. 138.

- Hibbert, p. 296.

- Acton, p. 145.

- Acton, pp. 144–145.

- Acton, p 148.

- Acton, p. 152.

- Acton, pp. 154–155.

- Acton, p. 155.

- Young, p. 464.

- Acton, p. 278.

- Acton, p. 279.

- Strathern, p. 389.

- Acton, p; 195.

- Acton, p. 196.

- Acton, p 273.

- Acton, p. 274.

- van de Pas, Leo; Fettes, Ian; Mahler, Leslie (3 November 1998). "Marguerite Louise d'Orléans, Mademoiselle d'Orléans". Genealogics. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- Anselme 1726, pp. 328–329.

- Anselme 1726, pp. 143–144.

- Anselme 1726, pp. 145–147.

- Anselme 1726, p. 211.

- "The Medici Granducal Archive and the Medici Archive Project" (PDF). p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2006.

- Leonie Frieda (14 March 2006). Catherine de Medici: Renaissance Queen of France. HarperCollins. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-06-074493-9. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- Wurzbach, Constantin, von, ed. (1860). . Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich [Biographical Encyclopedia of the Austrian Empire] (in German). Vol. 6. p. 290 – via Wikisource.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Cartwright, Julia Mary (1913). Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan and Lorraine, 1522–1590. New York: E. P. Dutton. p. 538.

- Anselme 1726, pp. 147–148.

- Anselme 1726, pp. 133–135.

- Bertholet, Jean (1742). Histoire ecclesiastique et civile du Duche de Luxembourg et Comte de Chiny (in French). Vol. 3. A. Chevalier. p. 39. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Messager des sciences historiques, ou, Archives des arts et de la bibliographie de Belgique (in French). Gand. 1883. p. 256.

Bibliography

- Acton, Harold (1980). The Last Medici. Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-29315-0

- Anselme de Sainte-Marie, Père (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France [Genealogical and chronological history of the royal house of France] (in French). Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). Paris: La compagnie des libraires.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1979). The Rise and Fall of the House of Medici. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-005090-5.

- Oresko, Robert (2004). "Maria Giovanna Battista of Savoy-Nemours (1644–1724): daughter, consort, and Regent of Savoy". In Campbell Orr, Clarissa (ed.). Queenship in Europe 1660–1815: The Role of the Consort. Cambridge University Press. pp. 16–55. ISBN 0-521-81422-7.

- Pitts, Vincent Joseph (2000). La Grande Mademoiselle at the Court of France. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6466-6.

- Strathern, Paul (2003). The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-952297-3.

- Young, G.F. (1920). The Medici: Volume II. John Murray.

External links

![]() Media related to Marguerite Louise d'Orléans at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Marguerite Louise d'Orléans at Wikimedia Commons