Men's skirts

Outside Western cultures, men's clothing commonly includes skirts and skirt-like garments; however, in the Americas and much of Europe, skirts are usually seen as feminine clothing and socially stigmatized for men and boys to wear, despite having done so for centuries.[1] While there are exceptions, most notably the cassock and the kilt, these are not really considered 'skirts' in the typical sense of fashion wear; rather they are worn as cultural and vocational garments. People have variously attempted to promote the fashionable wearing of skirts by men in Western culture and to do away with this gender distinction.

In Western cultures

Ancient times

Skirts have been worn since prehistoric times. They were the standard dressing for men and women in all ancient cultures in the Middle East.

The Kingdom of Sumer in Mesopotamia recorded two categories of clothing. The ritual attire for men was a fur skirt tied to a belt called Kaunakes. The term kaunakes, which originally referred to a sheep's fleece, was later applied to the garment itself. The animal pelts originally used were replaced by kaunakes cloth, a textile that imitated fleecy sheep skin.[2] Kaunakes cloth also served as a symbol in religious iconography, as the fleecy cloak of St. John the Baptist.[3][4]

Depictions of kings and their attendants from Babylonia on monuments like the Black Obelisk of Salmanazar show men wearing fringed cloths wrapped around their sleeved tunics.[5]

Ancient Egyptian garments were mainly made of white linen.[6] The exclusive use of draped linen garments, and the wearing of similar styles by men and women, remained almost unaltered as the main features of Ancient Egyptian costume. From about 2130 BC during the Old Kingdom of Egypt, men also wore wrap around skirts (kilts) known as the shendyt, They were made of a rectangular piece of cloth wrapped around the lower body and tied in front. By the Middle Kingdom of Egypt there was a fashion for longer kilts, almost like skirts, reaching from the waist to ankles, sometimes hanging from the armpits. During the New Kingdom of Egypt, kilts with a pleated triangular section became fashionable for men.[7] Beneath was worn a triangular loincloth, or shente, whose ends were fastened with cord ties.[8]

In Ancient Greece the simple, sleeved T-shaped tunics were constructed of three seamed tubes of cloth, a style that originated in the Semitic Near East, along with the Semitic-based word khiton, also referred to as a chiton.[9] The belted worn linen chiton was the primary garment for men and women.[10]

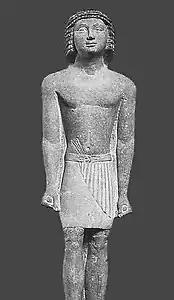

Statue of Ramaat, an official from Gizeh wearing a pleated Egyptian kilt, ca. 2.250 BC

Statue of Ramaat, an official from Gizeh wearing a pleated Egyptian kilt, ca. 2.250 BC A Greek charioteer from Delphi wearing a long chiton, ca. 470 BC

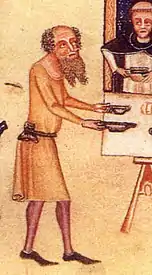

A Greek charioteer from Delphi wearing a long chiton, ca. 470 BC An illustration from between 1325 and 1335 showing an English man in a skirted garment

An illustration from between 1325 and 1335 showing an English man in a skirted garment Men's dress made of red silk (1480–90) to be buttoned on the front, History Museum of Bern (Switzerland)

Men's dress made of red silk (1480–90) to be buttoned on the front, History Museum of Bern (Switzerland) Duke Ulrich of Mecklenburg wearing a doublet and diverted skirt with codpiece and black tights, (1573)

Duke Ulrich of Mecklenburg wearing a doublet and diverted skirt with codpiece and black tights, (1573) Henry VIII wearing a doublet and diverted skirt with codpiece

Henry VIII wearing a doublet and diverted skirt with codpiece

The Romans adopted many facets of Greek culture, including the same manner of dressing. The Celts and Germanic peoples wore a skirted garment which the historian Diodorus Siculus (fl. 1st century BC) called chiton. Below they wore knee-length trousers. The Anglo-Saxons, Normans, Franks and other people of Western and Northern Europe continued this fashion well into the Middle Ages, as can be seen in the Bayeux Tapestry.[11]

.JPG.webp)

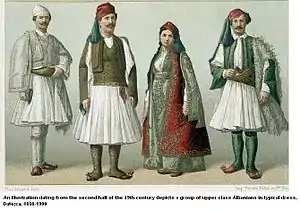

Technological advances in weaving with foot-treadle floor looms and the use of scissors with pivoted blades and handles in the 13–15th century led to new designs. The upper part of dresses could now be tailored exactly to the body. Men's dresses were buttoned on the front and women's dresses got a décolletage. The lower part of men's dresses were much shorter in length than those for women. They were wide cut and often pleated with an A-line so that horse riding became more comfortable. Even a knights armor had a short metal skirt below the breastplate. It covered the straps attaching the upper legs iron cuisse to the breastplate.[12][13] Other similar garments worn by men around the world include the Greek and Balkan fustanella (a short flared cotton skirt)

Decline

The innovative new techniques specially improved tailoring trousers and tights which designs needed more differently cut pieces of cloth than most skirts. "Real" trousers and tights increasingly replaced the prevalent use of the hose (clothing) which like stockings covered only the legs and had to be attached with garters to underpants or a doublet.[14] A skirt-like garment to cover the crotch and bottom were no longer necessary. In an intermediate stage to openly wearing trousers the upper classes favoured voluminous pantskirts and diverted skirts like the padded hose or the latter petticoat breeches.[15]

Though during most of history, men and especially dominant men have been colourful in pants and skirts like Hindu maharajas decked out in silks and diamonds or the high heeled King Louis XIV of France with a diverted skirt, stockings and long wig.[16] The French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution changed the dress code for men and women not only in France. From the early Victorian era, there was a decline in the wearing of bright colours and luxurious fabrics by men, with a definite preference for sobriety of dress.[17][18][19] This phenomenon the English psychologist John Flügel termed "The Great Masculine Renunciation".[20] Skirts were effeminized. "Henceforth trousers became the ultimate clothing for men to wear, while women had their essential frivolity forced on them by the dresses and skirts they were expected to wear".[21] By the mid-20th century, orthodox Western male dress, especially business and semi-formal dress, was dominated by sober suits, plain shirts and ties. The connotation of trousers as exclusively male has been lifted by the power of the feminist movement while the connotation of skirts as female is largely still existing leaving the Scottish kilt and the Albanian and Greek fustanella as the only traditional men's skirts of Europe.

Revival

In the 1960s, there was a widespread reaction against the accepted North American and European conventions of ”male and female dresses”. This unisex fashion movement aimed to eliminate the sartorial differences between men and women. In practice, it usually meant that women would wear male dresses, i.e. shirts and trousers. Men rarely went as far in the adoption of traditionally female dress modes.

Some exceptions were the costumes of pop musicians. Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones wore a white dress over white trousers for their 1969 Stones in the Park Concert, while David Bowie appeared in a patterned silk dress on the cover of his 1971 album 'The Man who sold the World'. Both men, particularly Bowie, experimented with androgynous fashion styles throughout the 1970s. [22][23][24]

However, the furthest most men went in the 1960s in adopting feminine attire were velvet trousers, flowered or frilled shirts, ties, and long hair.[25]

In the 1970s, David Hall, a former research engineer at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), actively promoted the use of skirts for men, appearing on both The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and the Phil Donahue Show. In addition, he was featured in many articles at the time.[26] In his essay "Skirts for Men: the advantages and disadvantages of various forms of bodily covering", he opined that men should wear skirts for both symbolic and practical reasons. Symbolically, wearing skirts would allow men to take on desirable female characteristics. In practical terms, skirts, he suggested, do not chafe around the groin, and they are more suited to warm climates.

In the early 1980s Boy George of successful pop group Culture Club brought androgynous dressing to a wide audience, wearing long skirts or dresses, makeup and long hair. [27][28]

1985 the French fashion designer Jean-Paul Gaultier created his first skirt for men. Transgressing social codes Gaultier frequently introduces the skirt into his men's wear collections as a means of injecting novelty into male attire, most famously the sarong seen on David Beckham.[29] Other famous designers such as Vivienne Westwood, Giorgio Armani, John Galliano, Kenzo, Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto also created men's skirts.[30] In the US Marc Jacobs became the most prominent supporter of the skirt for men. The Milan men's fashion shows and the New York fashion shows frequently show skirts for men. Jonathan Davis, the lead singer of Korn, has been known to wear kilts at live shows and in music videos throughout his 18-year career with that band. Mick Jagger from the Rolling Stones and Anthony Kiedis from the Red Hot Chili Peppers were photographed wearing dresses by Anton Corbijn.[31] For an FCKH8 anti-discrimination campaign Iggy Pop was seen wearing a black dress and handbag. Guns N' Roses' singer, Axl Rose, was known to wear men's skirts during the Use Your Illusion period. Robbie Williams and Martin Gore from Depeche Mode also performed on stage in skirts. During his Berlin time (1984–1985) Martin Gore was often seen in public wearing skirts. In an interview with the Pop Special Magazin (7/1985) he said: "Sexual barriers and gender roles are old fashioned and out. [...] I and my girlfriend often share our clothes and make-up". Brand Nubian Lord Jamar criticized Kanye West for wearing skirts, saying that his style has no place in hip-hop.[32][33]

In 2008 in France, an association was created to help spur the revival of the skirt for men.[34] Hot weather has also encouraged use. In June 2013, Swedish train drivers won the right to wear skirts in the summer when their cabins can reach up to 35 °C (95 °F),[35] whilst in July 2013, parents supported boys wearing skirts at Gowerton Comprehensive School in Wales.[36]

America is also not without its own contemporary advocates of skirts as menswear. One male blogger denies that skirts are exclusively feminine garments and suggests that the prevailing societal view reflects a "symbology of power" that persisted even in wake of the women's liberation movement.[37] He suggests an apparent causality paradox in the perception of skirts as exclusively womenswear: "are skirts perceived as feminine because women wear them or do women wear them because skirts are perceived as feminine?"[38] Though lamenting the lack of skirts designed specifically for men, he discusses in detail how to "advance a viewpoint of masculine aesthetics" in his how-to guide for men.[38] Other internet denizens echo these sentiments (with varying degrees of anonymity) in the "Skirt Cafe" internet forum "dedicated to exploring, promoting and advocating skirts and kilts as a fashion choice for men."[39] The forum's moderators conspicuously assert that "this is NOT a transvestite or crossdresser forum. We are committed to a fundamentally masculine gender identity."[40]

Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition

In 2003, the Metropolitan Museum of Art displayed an exhibition, organized by Andrew Bolton and Harold Koda of the Museum's Costume Institute and sponsored by Gaultier, entitled Bravehearts: Men in Skirts.[41] The idea of the exhibition was to explore how various groups and individuals (from hippies through pop stars to fashion designers) have promoted the idea of men wearing skirts as "the future of menswear". It displayed men's skirts on mannequins, as if in the window of a department store, in several historical and cross-cultural contexts.[42]

The exhibition display pointed out the lack of a "natural link" between an item of clothing and the masculinity or femininity of the wearer, mentioning the kilt as "one of the most potent, versatile, and enduring skirt forms often looked upon by fashion designers as a symbol of a natural, uninhibited, masculinity". It pointed out that fashion designers and male skirt-wearers employ the wearing of skirts for three purposes: to transgress conventional moral and social codes, to redefine the ideal of masculinity, and to inject novelty into male fashion. It linked the wearing of men's skirts to youth movements and countercultural movements such as punk, grunge, and glam rock and to pop-music icons such as Boy George, Miyavi and Adrian Young.[42] Many male musicians have worn skirts and kilts both on and off stage. The wearing of skirts by men is also found in the goth subculture.

Elizabeth Ellsworth, a professor of media studies,[43] eavesdropped on several visitors to the exhibition, noting that because of the exhibition's placement in a self-contained space accessed by a staircase at the far end of the museum's first floor, the visitors were primarily self-selected as those who would be intrigued enough by such an idea in the first place to actually seek it out. According to her report, the reactions were wide-ranging, from the number of women who teased their male companions about whether they would ever consider wearing skirts (to which several men responded that they would) to the man who said, "A caftan after a shower or in the gym? Can you imagine? 'Excuse me! Coming through!'". An adolescent girl rejected in disgust the notion that skirts were similar to the wide pants worn by hip-hop artists. Two elderly women called the idea "utterly ridiculous". One man, reading the exhibition's presentation on the subject of male skirt-wearing in cultures other than those in North America and Europe, observed, "God! Three quarters of the world's population [wear skirts]!"[42]

The exhibition itself attempted to provoke visitors into considering how, historically, male-dress codes have come to this point and whether in fact a trend towards the wearing of skirts by men in the future actually exists. It attempted to raise challenging questions of how a simple item of dress connotes (in Ellsworth's words) "huge ramifications in meanings, behaviours, everyday life, senses of self and others, and configurations of insider and outsider".[42]

Other exhibitions

A number of men's skirts and skirted garments featured in the 2022 exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London entitled Fashioning Masculinities: the art of menswear,[44][45] which illustrated the history of men's fashion in western Europe, and its relationship to perceptions of masculinity, using historical and contemporary material.

Contemporary styles

The wearing of skirts, kilts, or similar garments on an everyday basis by men in Western cultures is an extremely small minority. One manufacturer of contemporary kilt styles claims to sell over 12,000 such garments annually,[46] resulting in over $2 million annually worth of sales, and has appeared at a major fashion show.[47] According to a CNN correspondent: "At Seattle's Fremont Market, men are often seen sporting the Utilikilt."[48] In 2003, US News said that "... the Seattle-made utilikilt, a rugged, everyday riff on traditional Scottish garb, has leapt from idea to over 10,000 sold in just three years, via the Web and word of mouth alone."[49] "They've become a common sight around Seattle, especially in funkier neighbourhoods and at the city's many alternative cultural events. They often are worn with chunky black boots," writes AP reporter Anne Kim.[50] "I actually see more people wearing kilts in Seattle than I did when I lived in Scotland," one purchaser remarked in 2003.[51]

In addition, since the mid-1990s, a number of clothing companies have been established to sell skirts specifically designed for men. These include Macabi Skirt in the 1990s, Menintime in 1999, Midas Clothing in 2002[52] and Skirtcraft in 2015.[53]

In 2010, the fashion chain H&M featured skirts for men in its lookbook.[54]

In 2018, Zara added a skirt for men in its Reshape collection.[55]

Wicca and neo-paganism

In Wicca and neopaganism, especially in the United States, men (just as women) are encouraged to question their traditional gender roles. Amongst other things, this involves the wearing of robes at festivals and sabbat celebrations as ritual clothing (which Eilers equates to the "church clothes" worn by Christians on Sundays).[56][57] Some denominations (called 'traditions') of Wicca even encourage their members to include robes, tunics, cloaks, and other such garments in their day-to-day wardrobes.

In non-Western cultures

Outside Western cultures, male clothing includes skirts and skirt-like garments.[58] One common form is a single sheet of fabric folded and wrapped around the waist, such as the dhoti, veshti or lungi in India, and the sarong in Southeast Asia. In Myanmar both women and men wear a longyi, a wraparound tubular skirt that reaches to the ankles for women and to mid-calf for men.[59] There are different varieties and names of sarong depending on whether the ends are sewn together or simply tied. There is a difference in the way a dhoti and lungi is worn. While a lungi is more like a wrap around, wearing the dhoti involves the creation of pleats by folding it. A dhoti also passes between the legs making it more like a folded loose trouser rather than a skirt.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, sarong-like garments sometimes worn by men are known as kanga (or khanga), kitenge (or chitenje), kikoy, and lappa.[60] In Madagascar they are known as lamba. In West Africa Ghanaian chiefs use the iconic kente cloths for their representative chiton-like wraparound garments. Extremely beautiful are the leather skirts and finely embroidered tunics of the Wodaabe in Niger, which the men wear to display their enhanced beauty and to impress the unmarried women on the Gerewol dance festivals.[61] In Central Africa the formal attire of a Kuba official needs a red-black-white raffia-cloth skirt with bobble fringe.[62]

The Samoan Lavalava is a wraparound "skirt". These are worn by men, women and children. The women's lavalava pattern usually have either traditional symbols and/or a flower (frangipani) pattern. The men's lavalava have only traditional symbols. A blue lavalava is the official skirt for the police officers uniform of Samoa.

In Sikhism, a faith that originated in the Punjab, there is a traditional dress which is worn by both men and women, called a 'baana' or 'chola'. This dress has a skirted bottom and is worn over long white undershorts. It was traditionally worn in battle by Sikh warriors as it allowed free movement and remains a part of the traditional Sikh dress and identity.

For the hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, Muslim men wear the ihram, a simple, seamless garment made of white, terry clothlike cotton. One piece is wound skirt-like around the lower half of the body; the other is thrown loosely over one shoulder.[63] The Qahtani sheep herders in the Southern Asir provence wear ankle-length skirt-like kilts. In Yemen standard dress is a calf-length, wraparound skirt, the futah. The Palestinians of the Eastern Mediterranean traditionally wear the qumbaz, an ankle-length unisex garment, which opens all the way down the front with the right side brought over the left, under the arm, and then fastened.[64]

The Pacific lava-lava (similar to a sarong), the Fijian sulu vakataga,[65] some forms of Japanese hakama and the Bhutanese gho. The Fijian sulu is a long bark cloth skirt for men as well as women. It is still worn as Fijian national dress, in one of the more obvious versions of invented traditions, though today the cloth will be cotton or other woven material. A Fijian aristocrat will even wear a pin-stripe sulu to accompany a dress and tie, as full court dress.[66]

In China, skirts that are called qun (裙) or chang (裳) in Chinese were also worn by men, as well as robes known as paofu and shenyi, from ancient times until the end of the Qing dynasty in 1911. The Qin warriors of the first dynasty of Imperial China, wore a skirt-like tunic and a protective cuirass of bronze plates as can be seen on the excavated figures of the famous Terracotta Army; the entertainers figures together with the Terracotta Army also wore short skirts varying from knee-length to mid-thighs.[67] Portraits and statues of the revered Chinese scholar, Confucius show him wearing ample, enveloping silk robes.[68]

In Japan there are two types of the hakama for men to wear, the divided umanori (馬乗り, "horse-riding hakama") and the undivided andon hakama (行灯袴, "lantern hakama"). The umanori type has divided legs, similar to diverted skirts and pantskirts. The hakama is everyday attire for Shinto kannushi priests who perform services at shrines. Until the 1940s the hakama used to be a required part of common men's wear. Today Japanese men usually wear the hakama only on formal occasions like tea ceremonies, weddings, and funerals. The hakama is also worn by practitioners of a variety of martial arts, such as kendo.[69]

In popular culture

One notable example of men wearing skirts in fiction is in early episodes of the science fiction TV program Star Trek: The Next Generation. The uniforms worn in the first and second season included a variant consisting of a short sleeved top, with attached skirt. This variant was seen worn by both male and female crew members. The book The Art of Star Trek explained that "the skirt design for men 'skant' was a logical development, given the total equality of the sexes presumed to exist in the 24th century."[70] However, perhaps reflecting the expectations of the audience, the "skant" was dropped by the third season of the show.

Other examples

- Link from The Legend of Zelda series often wears a long tunic

Dance

In some Western dance cultures, men commonly wear skirts and kilts. These include a broad range of professional dance productions where they may be worn to improve the artistic effect of the choreography,[71] a style known as contra dance, where they are worn partly for ventilation and partly for the swirling movement, gay line dancing clubs where kilts are often worn,[72] and revellers in Scottish nightclubs where they are worn to express cultural identity.

See also

References

- Critchell, Samantha (14 November 2003). "Exhibit makes case for manly men in skirts". Cape Cod Times. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- Boucher, Francois (1987): 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment. New York: Harry N. Abrams

- The Bible: Genesis 12:4–5

- Roberts, J.M. (1998): The Illustrated History of the World. Time-Life Books. Volume 1. p. 84

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 22

- Barber, Elisabeth J.W. (1991): Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 12.

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 25

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 24

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 88

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 89

- Koch-Mertens, Wiebke (2000): Der Mensch und seine Kleider: Die Kulturgeschichte der Mode bis 1900. Düsseldorf Zürich. Artemis & Winkler, p. 114.

- Tortora, Phyllis et al. (2014): Dictionary of Fashion. New York: Fairchild Books. p. 11.

- Koch-Mertens, Wiebke (2000): Der Mensch und seine Kleider: Die Kulturgeschichte der Mode bis 1900. Düsseldorf Zürich. Artemis & Winkler, pp. 156–162.

- Koch-Mertens, Wiebke (2000): Der Mensch und seine Kleider: Die Kulturgeschichte der Mode bis 1900. Düsseldorf Zürich. Artemis & Winkler, p 130

- Koch-Mertens, Wiebke (2000): Der Mensch und seine Kleider: Die Kulturgeschichte der Mode bis 1900. Düsseldorf Zürich. Artemis & Winkler, pp. 216–217

- Noah Harari, Yuval (2014): Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Vintage-books. pp. 168, 169

- Ribeiro, Aileen (2003): Dress and Morality. Berg Publishers. p. 169.

- Fiona Margaret Wilson (2003). Organizational Behaviour and Gender. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 199. ISBN 0-7546-0900-6.

- Jennifer Craik (1994). The Face of Fashion: culture studies in fashion. Routledge. pp. 200. ISBN 0-415-05262-9.

- Ross, Robert (2008): Clothing: A Global History. Cambridge: Polity. pp. 35, 36

- Ross, Robert (2008): Clothing: A Global History. Cambridge: Polity. p. 59

- Perrott, Lisa (11 January 2016). "How David Bowie blurred gender lines". CNN. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- "David Bowie Proved That Style Has No Gender — Over 40 Years Ago". Mic. 11 January 2016. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- Trzcinski, Matthew (2020-08-12). "Mick Jagger on Why Androgyny Is Part of Rock 'n' Roll". Showbiz Cheat Sheet. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- Ribeiro, Aileen (2003). Dress and Morality. Berg Publishers. p. 169. ISBN 1-85973-782-X.

- "Lakeland Ledger - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- Everyday, Vintage (2020-06-14). "30 Flamboyant Photos of Boy George at the Height of His Fame During the 1980s". Vintage News Daily. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- Casiano, Christina (2022-06-14). "Boy George Then & Now Photos: The Culture Club Rocker Through The Years". Hollywood Life. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- Fogg, Marnie (2011) The Fashion Design Directory. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 165.

- Fogg, Marnie (2011) The Fashion Design Directory. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 316.

- Corbijn, Anton (2000): Werk. Schirmer/ Mosel (Germany). p. 70

- djvlad (1 February 2013). "Lord Jamar: Kanye's Skirt Has No Place in Hip-Hop". Archived from the original on 2021-12-21 – via YouTube.

- JungleBookJokes (19 January 2013). "Kanye West Was Serious About His Skirt Kilt". Archived from the original on 2021-12-21 – via YouTube.

- Lizzy Davies (2008-08-04). "The Frenchmen fighting for the right to wear skirts". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited.

- "Sweden's Arriva lifts shorts ban for skirt-wearing drivers". BBC News. 10 June 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- "Swansea schoolboys keep cool in skirts after shorts ban". Daily Telegraph. 15 Jul 2013. Archived from the original on 16 July 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- "Why I Wear Skirts". 28 Nov 2016. Retrieved 3 Oct 2018.

- "A Guy's Guide to Getting Skirted". 14 Feb 2018. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 3 Oct 2018.

- "Introduction and Summary of the Rules". Skirt Cafe. 27 Aug 2007. Retrieved 3 Oct 2018.

- "Introduction and Summary of the Rules". Skirt Cafe. 27 Aug 2007. Retrieved 3 Oct 2018.

- Bolton, Andrew (2003). Bravehearts: Men in Skirts. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-6558-5.

- Elizabeth Ann Ellsworth (2005). Places of Learning Media, Architecture, Pedagogy. Routledge. pp. 143–146. ISBN 0-415-93158-4.

- "Elizabeth Ellsworth - Professor of Media Studies - Public Engagement". www.newschool.edu.

- "Fashioning Masculinities: the art of menswear". www.vam.ac.uk.

- McKever, Rosalind; Wilcox, Claire; Franceschini, Marta (2022). Fashioning Masculinities: the art of menswear. V&A Publishing. ISBN 978-183851011-4.

- Staff (September 19, 2005). "It's a cargo skirt – for guys". Toledo, Ohio: WTVG-TV News.

- Craig Harris (2007-01-26). "Manly skirt is not just for Scots anymore". Seattle Post-Intelligencer (online edition). Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- "Tailor Revives Art of Kilt-Making". Sunday Morning News. CNN. January 7, 2001. Archived from the original on 2021-03-07. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

At Seattle's Fremont Market, men are often seen sporting the Utilikilt

- "Escaping the tyranny of trousers". U.S. News & World Report. May 5, 2003. Archived from the original on March 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- Anne Kim (October 1, 2005). "Utilikilt makes 'short' work of job for men". The Ara\izona Republic (Online edition). Retrieved 2007-05-18.

They've become a common sight around Seattle, especially in funkier neighborhoods and at the city's many alternative cultural events.

- Chelan David (March 12, 2003). "Kilts coming back in fashion" (PDF). Ballard New-Tribune. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

Mackay is amazed at the amount of kilts he sees in Seattle. "I actually see more people wearing kilts in Seattle than I did when I lived in Scotland," he marvels.

- "Men's skirts sew success". BBC News. 2003-06-27. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- Raquel Laneri (2016-10-01). "Macho men are wearing skirts now". NY Post.

- "H&M Offers Skirts for Men This Spring". nbcnewyork.com. 25 November 2009.

- "Wrap skirt — Reshape — Shop by collection — Man". ZARA United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- Helen A. Berger (1999). A Community of Witches: Contemporary Neo-paganism and Witchcraft in the United States. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 43. ISBN 1-57003-246-7.

- Dana D. Eilers (2002). The Practical Pagan: Common Sense Guidelines for Modern Practitioners. Career Press. p. 153. ISBN 1-56414-601-4.

- Lisa Lenoir (2003-12-11). "Men in Skirts". Chicago Sun-Times. The Chicago Sun-Times Inc.

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 265

- "rahsgeo - Nigeria". rahsgeo.wikispaces.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-27. Retrieved 2012-03-31.

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 552, 560

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 540

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 53

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 61

- Findlay, Rosie (29 January 2014). "Why don't more men wear skirts?". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016.

- Ross, Robert (2008): Clothing: A Global History. Cambridge: Polity. p. 92

- Fennell, Carolyn (2018-01-11). "On "Skirts" and "Trousers" in the Qin Dynasty Manuscript Making Clothes in the Collection of Peking University*". East View Press. Retrieved 2022-07-30.

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 156–174.

- Rief Anawalt, Patricia (2007): The Worldwide History of Dress. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 199–203

- Reeves-Stevens, Judith & Garfield. The Art of Star Trek. New York:Pocket Books, 1995. ISBN 0671898043

- Dance magazine, October 2000 – "Dress for Success – skirts for men common in dance productions" http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1083/is_10_74/ai_65862860

- Timeout magazine: London's gay Scottish linedancers "London's gay Scottish linedancers - Features - Gay - Time Out London". Archived from the original on 2007-07-04. Retrieved 2007-07-30.