Malay race

The concept of a Malay race was originally proposed by the German physician Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840), and classified as a brown race.[1][2] Malay is a loose term used in the late 19th century and early 20th century to describe the Austronesian peoples.[3][4]

_(14782056275).jpg.webp)

Since Blumenbach, many anthropologists have rejected his theory of five races, citing the enormous complexity of classifying races. The concept of a "Malay race" differs with that of the ethnic Malays centered on Malaya and parts of the Malay Archipelago's islands of Sumatra and Borneo.

History

The linguistic connections between Madagascar, Polynesia and Southeast Asia were recognized early in the colonial era by European authors, particularly the remarkable similarities between Malagasy, Malay, and Polynesian numerals.[5] The first formal publications on these relationships was in 1708 by the Dutch Orientalist Adriaan Reland, who recognized a "common language" from Madagascar to western Polynesia; although the Dutch explorer Cornelis de Houtman also realized the linguistic links between Madagascar and the Malay Archipelago prior to Reland in 1603.[6]

The Spanish philologist Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro later devoted a large part of his Idea dell' Universo (1778–1787) to the establishment of a language family linking the Malayan Peninsula, the Maldives, Madagascar, the Sunda Islands, Moluccas, the Philippines, and the Pacific Islands eastward to Easter Island. Multiple other authors corroborated this classification (except for the erroneous inclusion of Maldivian), and the language family came to be known as "Malayo-Polynesian," first coined by the German linguist Franz Bopp in 1841 (German: malayisch-polynesisch).[5][7] The connections between Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands were also noted by other European explorers, including the orientalist William Marsden and the naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster.[3]

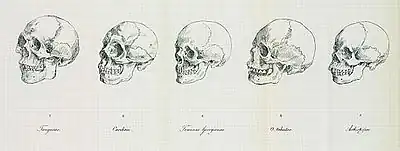

In his 1775 doctoral dissertation titled De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa (trans: On the Natural Varieties of Mankind), Blumenbach outlined Johann Friedrich Blumenbach main human races by skin color, geography, and skull measurements; namely "Caucasians" (white), "Ethiopians" (black), "Americans" (red), and the "Mongolians" (yellow). Blumenbach added Austronesians as the fifth category to his "varieties" of humans in the second edition of De Generis (1781). He initially grouped them by geography and thus called Austronesians the "people from the southern world." In the third edition published in 1795, he named Austronesians the "Malay race" or the "brown race," after studies done by Joseph Banks who was part of the first voyage of James Cook.[3][8] Blumenbach used the term "Malay" due to his belief that most Austronesians spoke the "Malay idiom" (i.e. the Austronesian languages), though he inadvertently caused the later confusion of his racial category with the Melayu people.[9] Blumenbach's definition of the Malay race is largely identical to the modern distribution of the Austronesian peoples, including not only Islander Southeast Asians, but also the people of Madagascar and the Pacific Islands. Although Blumenbach's work was later used in scientific racism, Blumenbach was a monogenist and did not believe the human "varieties" were inherently inferior to each other. However he believed in the "degenerative hypothesis", and believed that the Malay race were a transitory form between Caucasians and Ethiopians.[3][8]

Malay variety. Tawny-coloured; hair black, soft, curly, thick and plentiful; head moderately narrowed; forehead slightly swelling; nose full, rather wide, as it were diffuse, end thick; mouth large, upper jaw somewhat prominent with parts of the face when seen in profile, sufficiently prominent and distinct from each other. This last variety includes the islanders of the Pacific Ocean, together with the inhabitants of the Mariannas, the Philippine, the Molucca and the Sunda Islands, and of the Malayan peninsula. I wish to call it the Malay, because the majority of the men of this variety, especially those who inhabit the Indian islands close to the Malacca peninsula, as well as the Sandwich, the Society, and the Friendly Islanders, and also the Malambi of Madagascar down to the inhabitants of Easter Island, use the Malay idiom.

— Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, The anthropological treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, translated by Thomas Bendyshe, 1865.[10]

By the 19th century, however, scientific racism was favoring a classification of Austronesians as being a subset of the "Mongolian" race, as well as polygenism. The Australo-Melanesian populations of Southeast Asia and Melanesia (whom Blumenbach initially classified as a "subrace" of the "Malay" race) were also now being treated as a separate "Ethiopian" race by authors like Georges Cuvier, Conrad Malte-Brun, Julien-Joseph Virey, and René Lesson.[3]

The British naturalist James Cowles Prichard originally followed Blumenbach by treating Papuans and Native Australians as being descendants of the same stock as Austronesians. But by his third edition of Researches into the Physical History of Man (1836-1847), his work had become more racialized due to the influence of polygenism. He classified the peoples of Austronesia into two groups: the "Malayo-Polynesians" (roughly equivalent to the Austronesian peoples) and the "Kelænonesians" (roughly equivalent to the Australo-Melanesians). He further subdivided the latter into the "Alfourous" (also "Haraforas" or "Alfoërs", the Native Australians), and the "Pelagian or Oceanic Negroes" (the Melanesians and western Polynesians). Despite this, he acknowledges that "Malayo-Polynesians" and "Pelagian Negroes" had "remarkable characters in common", particularly in terms of language and craniometry.[3][5][7]

In 1899, the Austrian linguist and ethnologist Wilhelm Schmidt coined the term "Austronesian" (German: austronesisch, from Latin auster, "south wind"; and Greek νῆσος, "island") to refer to the language family.[11] The term "Austronesian", or more accurately "Austronesian-speaking peoples", came to refer the people who speak the languages of the Austronesian language family.[12][13]

Colonial influences

The view of Malays held by Stamford Raffles had a significant influence on English-speakers, lasting to the present day. He is probably the most important voice who promoted the idea of a ‘Malay’ race or nation, not limited to the Malay ethnic group, but embracing the people of a large yet unspecified part of the South East Asian archipelago. Raffles formed a vision of Malays as a language-based 'nation', in line with the views of the English Romantic movement at the time, and in 1809 sent a literary essay on the topic to the Asiatic Society. After he mounted an expedition to the former Minangkabau seat of royalty in the Pagaruyung, he declared it was ‘the source of that power, the origin of that nation, so extensively scattered over the Eastern Archipelago’.[14] In his later writings he moved the Malays from a nation to a race.[15]

Usage

Brunei

In Brunei, "indigenous Malays" (Malay: Melayu Jati) refer to people who belong to one of the seven ethnic groups: Brunei Malay, Kedayan, Tutong, Dusun, Belait, Bisaya and Murut.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the term "Malay" (Indonesian: Melayu) is more associated with ethnic Malay than 'Malay race'. Historically the term 'Malay race' was first coined by foreign scientists in colonial times. However during the Dutch East Indies era, all natives were grouped under the category inlanders or pribumi to describe native Indonesians in contrast to Eurasian Indo people and Asian immigrants (Chinese, Arab and Indian origin). Native Indonesian were diverse and included ethnicities that have their own culture, identity, traditions and languages that are very different from coastal Malay people. Thus, making Malay just as one of myriad Indonesian ethnicities, sharing common status with Javanese (including their sub-ethnic such as Osing and Tenggerese), Sundanese, Minangkabau, Batak tribes, Bugis, Dayak peoples, Acehnese, Balinese, Torajan, Moluccans and Papuans. Hence Indonesian nationalism and identity that manifested afterward was a civic nationalism rather than ethnic nationalism based on Malay race.[16][17] This was expressed by Youth Pledge during 2nd Youth Congress in 1928 with the proclamation of a united motherland of Indonesia, united Indonesia nation or bangsa Indonesia rather than ethnic identities, and advocated the use of local Malay language dialect as Indonesian language.

The concept of the Malay race as in Malaysia and to some degree, the Philippines, also influenced and might be shared by some Indonesians in the spirit of inclusivity and solidarity, commonly coined as puak Melayu or rumpun Melayu. However, the idea and the degree of 'Malayness' also varies in Indonesia, from covering the vast area of Austronesian people to confining it only within the Jambi area where the name 'Malayu' was first recorded.[18] Today, the common identity that binds Malay people together is their language (with variants of Indonesian language dialects that exist among them), their culture norms, and for some Islam.[19]

Malaysia

In Malaysia, the early colonial censuses listed separate ethnic groups, such as "Malays, Boyanese, Achinese, Javanese, Bugis, Manilamen (Filipino) and Siamese". The 1891 census merged these ethnic groups into the three racial categories used in modern Malaysia—Chinese, ‘Tamils and other natives of India’, and ‘Malays and other Natives of the Archipelago’. This was based upon the European view at the time that race was a biologically based scientific category. For the 1901 census, the government advised the word "race" should replace "nationality" wherever it occurs.[15][9]

After a period of generations of being classified in these groups, individual identities formed around the concept of bangsa Melayu (Malay race). For younger generations of people, they saw it as providing unity and solidarity against colonial powers, and non-Malay immigrants. The Malaysian nation was later formed with the bangsa Melayu having the central and defining position within the country.[15]

Philippines

In the Philippines, many Filipinos consider the term "Malay" to refer to the indigenous population of the country as well as the indigenous populations of neighboring Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei. This misconception is due in part to American anthropologist H. Otley Beyer, who had proposed that Filipinos were actually Malays who migrated north from what are now Malaysia and Indonesia. This idea was in turn propagated by Filipino historians and is still taught in many schools. However, the prevalent consensus among contemporary anthropologists, archaeologists, and linguists actually proposes the reverse; namely that ancestors of the Austronesian peoples of the Sunda Islands, Madagascar, and Oceania had originally migrated south from the Philippines during the prehistoric period from an origin in Taiwan.[20][21]

Although Beyer's theory is now completely rejected by modern anthropologists, the misconception remains and most Filipinos still conflate Malay with Austronesian identity, almost always equating the two. Common usage of term "Malay" does not just refer to the ethnic Malays of other Southeast Asian countries. The academic term "Austronesian" remains unfamiliar to most Filipinos.[22][23][24][25]

Singapore

United States

In the United States, the racial classification "Malay race" was introduced in the early twentieth century into the anti-miscegenation laws of a number of western US states. Anti-miscegenation laws were state laws that prohibited marriage between European Americans and African Americans and in some states also other non-whites. After an influx of Filipino immigrants, these existing laws were amended in a number of western states to prohibit marriage between Caucasians and Filipinos, who were designated as members of the Malay race, and a number of Southern states committed to racial segregation followed suit. Eventually, nine states (Arizona, California, Georgia, Maryland, Nevada, South Dakota, Utah, Virginia, and Wyoming) explicitly prohibited marriage between Caucasians and Filipinos.[26] In California, there was some confusion over whether pre-existing state laws prohibiting marriage between whites and "Mongolians" also prohibited marriage between whites and Filipinos. A 1933 Supreme Court of California case Roldan v. Los Angeles County concluded that such marriages were legal as Filipinos were members of the "Malay race" and were not enumerated in the list of races for whom marriage with whites was illegal. The California legislature soon after amended the laws to extend the prohibition against interracial marriage to whites and Filipinos.[27][28]

Many anti-miscegenation laws were gradually repealed after the Second World War, starting with California in 1948. In 1967, all remaining bans against interracial marriage were judged to be unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia and therefore repealed.

See also

References

- University of Pennsylvania

- "Johann Frederich Blumenbach". Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Douglas, Bronwen (2008). "'Novus Orbis Australis': Oceania in the science of race, 1750-1850". In Douglas, Bronwen; Ballard, Chris (eds.). Foreign Bodies: Oceania and the Science of Race 1750-1940 (PDF). ANU E Press. pp. 99–156. ISBN 9781921536007.

- Rand McNally's World Atlas International Edition Chicago:1944 Rand McNally Map: "Races of Mankind" Pages 278–279—On the map, the group called the Malayan race is shown as occupying an area on the map (consisting mainly of the islands of what was then called the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, Madagascar, and the Pacific Islands, as well as the continental Malay Peninsula) identical and coextensive with the extent of the land area inhabited by those people now called Austronesians.

- Crowley T, Lynch J, Ross M (2013). The Oceanic Languages. Routledge. ISBN 9781136749841. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Blust, Robert A. (2013). The Austronesian languages. Asia-Pacific Linguistics. Australian National University. hdl:1885/10191. ISBN 9781922185075.

- Ross M (1996). "On the Origin of the Term 'Malayo-Polynesian'". Oceanic Linguistics. 35 (1): 143–145. doi:10.2307/3623036. JSTOR 3623036.

- Bhopal, Raj (22 December 2007). "The beautiful skull and Blumenbach's errors: the birth of the scientific concept of race". BMJ. 335 (7633): 1308–1309. doi:10.1136/bmj.39413.463958.80. PMC 2151154. PMID 18156242.

- "Pseudo-theory on origins of the 'Malay race'". Aliran. 19 January 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-10. Retrieved 2006-09-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Simpson, John; Weiner, Edmund, eds. (1989). Official Oxford English Dictionary (OED2) (Dictionary). Oxford University Press. p. 22000.

- Bellwood P, Fox JJ, Tryon D (2006). The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Australian National University Press. ISBN 9781920942854. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Blench, Roger (2012). "Almost Everything You Believed about the Austronesians Isn't True" (PDF). In Tjoa-Bonatz, Mai Lin; Reinecke, Andreas; Bonatz, Dominik (eds.). Crossing Borders. National University of Singapore Press. pp. 128–148. ISBN 9789971696429. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Lady Sophia Raffles (1830). Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. John Murray. p. 360.

- Reid, Anthony (2001). "Understanding Melayu (Malay) as a Source of Diverse Modern Identities". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 32 (3): 295–313. doi:10.1017/S0022463401000157. PMID 19192500. S2CID 38870744.

- Anderson, Benedict R. O'G. (1991). Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Revised and extended. ed.). London: Verso. pp. . ISBN 978-0-86091-546-1. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Vandenbosch, Amry (1952). "Nationalism and Religion in Indonesia". Far Eastern Survey. 21 (18): 181–185. doi:10.2307/3023866. JSTOR 3023866. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- "Redefinisi Melayu: Upaya Menjembatani Perbedaan Kemelayuan Dua Bangsa Serumpun". Archived from the original on 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Melayu Online (2010-08-07). "Melayu Online.com's Theoretical Framework". Melayu Online. Archived from the original on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- Gray, RD; Drummond, AJ; Greenhill, SJ (2009). "Language Phylogenies Reveal Expansion Pulses and Pauses in Pacific Settlement". Science. 323 (5913): 479–483. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..479G. doi:10.1126/science.1166858. PMID 19164742. S2CID 29838345.

- Pawley, A. (2002). "The Austronesian dispersal: languages, technologies and people". In Bellwood, Peter S.; Renfrew, Colin (eds.). Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge. pp. 251–273. ISBN 1902937201.

- Acabado, Stephen; Martin, Marlon; Lauer, Adam J. (2014). "Rethinking history, conserving heritage: archaeology and community engagement in Ifugao, Philippines" (PDF). The SAA Archaeological Record: 13–17.

- Lasco, Gideon (28 December 2017). "Waves of migration". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Palatino, Mong (27 February 2013). "Are Filipinos Malays?". The Diplomat. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Curaming, Rommel (2011). "The Filipino as Malay: historicizing an identity". In Mohamad, Maznah; Aljunied, Syed Muhamad Khairudin (eds.). Melayu: Politics, Poetics and Paradoxes of Race. Singapore University Press. pp. 241–274. ISBN 9789971695552.

- Pascoe, Peggy, "Miscegenation Law, Court Cases, and Ideologies of "Race" in Twentieth Century America, The Journal of American History, Vol. 83, June 1996, p. 49

- Moran, Rachel F. (2003), Interracial Intimacy: The Regulation of Race and Romance, University of Chicago Press, p. 206, ISBN 978-0-226-53663-7

- Min, Pyong-Gap (2006), Asian Americans: contemporary trneds and issues, Pine Forge Press, p. 189, ISBN 978-1-4129-0556-5

Further reading

- Roque, Ricardo (15 October 2018). "The colonial ethnological line: Timor and the racial geography of the Malay Archipelago". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 49 (3): 387–409. doi:10.1017/S0022463418000322. S2CID 165228012.