Mad cow crisis

The mad cow crisis is a health and socio-economic crisis characterized by the collapse of beef consumption in the 1990s, as consumers became concerned about the transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) to humans through the ingestion of this type of meat.

Background

BSE is a degenerative infection of the central nervous system in cattle. It is a fatal disease, similar to scrapie in sheep and goats, caused by a prion. A major epizootic affected the UK, and to a lesser extent a number of other countries, between 1986 and the 2000s, infecting more than 190,000 animals, not counting those that remained undiagnosed.

The epidemic is thought to have originated in the feeding of cattle with meat and bone meal, obtained from the uneaten parts of cattle and animal cadavers. The epidemic took a particular turn when scientists realized in 1996 that the disease could be transmitted to humans through the consumption of meat products.

As of 24 January 2017, the disease had claimed 223 human victims worldwide (including 177 in the UK and 27 in France)[1] affected by symptoms similar to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a disease of the same nature as BSE.

Communicated to the general public by the media, the crisis erupted in 1996. It involved both ethical aspects, with consumers becoming aware of certain practices that were common in livestock farming but of which they had been unaware, such as the use of meat and bone meal, and economic aspects, with the ensuing fall in beef consumption and the cost of the various measures adopted.

Various measures were taken to curb the epidemic and safeguard human health, including a ban on the use of meat and bone meal in cattle feed, the withdrawal from consumption of products considered to be at risk, and even of certain animals (animals over 30 months of age in the UK), screening for the disease in slaughterhouses, and the systematic slaughter of herds where a sick animal had been observed.

Nowadays, the epidemic is almost completely under control, despite 37 bovine cases still being diagnosed in the UK in 2008.

On 23 March 2016, a new case of mad cow disease was detected in France in the Ardennes department. This is the third isolated case of BSE of this type detected in Europe since 2015.[2]

Other human cases could nevertheless appear in the future, as the incubation period of the disease can be long. The mad cow crisis has left a legacy of improved practices in the beef industry, through the removal of certain parts of the cadaver at the slaughterhouse during cutting, as well as enhanced animal traceability. In terms of public health, this crisis has also led to a strengthening of the precautionary principle.

Epidemiology

The disease was first identified in Great Britain in 1986.

Symptoms

%252C_typical_amyloid_plaques%252C_H%2526E.jpg.webp)

BSE affects the brain and spinal cord of cattle. It causes brain lesions characterized by spongy changes visible under the light microscope, corresponding to vacuolated neurons. Neurons are lost to varying degrees, and astrocytes and microglia (brain cells with an immune function) multiply. Pathogens accumulate to form characteristic amyloid plaques, though these are less prevalent than in other transmissible spongiform encephalopathies.[3]

External symptoms generally appear 4 to 5 years after contamination, and always in animals over 2 years of age (generally between 3 and 7 years). Initially, they are manifested by a change in the animal's behavior (nervousness and aggressiveness[4]), which may sometimes kick, show apprehension and hypersensitivity to external stimuli (noise, touch, dazzle), and isolate itself from the rest of the herd. Milk production and weight generally decrease, while appetite remains unchanged. Progression can last from a week to a year, with the different phases of the disease varying in duration from one animal to another. In the final stage of evolution, the animal has real locomotion problems. They frequently lose their balance, sometimes unable to stand up again.

Physiologically, the animal is tachycardic and feverless. However, the appearance of these symptoms is not a sure sign of BSE. In fact, locomotor disorders such as grass tetany are common in cattle, making diagnosis of the disease difficult.[5]

An unconventional pathogen

The actual nature of the infectious agent is the subject of much debate. The theory now widely accepted by the scientific community is that of the prion, a protein which, in the case of the disease, adopts an abnormal conformation that can be transmitted to other healthy prion proteins. An alternative theory is the viral agent, which would more easily explain the agent's ability to generate multiple strains. It is a so-called resistant form of the prion (PRoteinasceous Infectious ONly) that is responsible for the disease. The proteins accumulate in the brain, eventually leading to neuron death and the formation of amyloid plaques.[6]

As a protein, the prion has no metabolism of its own, and is therefore resistant to freezing, desiccation and heat at normal cooking temperatures, even those reached for pasteurization and sterilization.[7] In fact, to be destroyed, the prion must be heated to 133 °C for 20 minutes at 3 bars of pressure.[8]

Origins of the epizootic

The origins of the BSE pathogen are uncertain. Two hypotheses are widely supported. The first is that the disease originated through interspecific contamination from a closely related disease, scrapie. The possibility of interspecific transmission of scrapie has been proven experimentally, but the clinical and neuropathological disorders associated with the disease differ from those of bovine spongiform encephalopathy. This observation led to the formulation of a second hypothesis, according to which the disease is endemic to the bovine species, and very thinly spread before it was amplified in the mid-1980s.[7] The description in an 1883 veterinary journal of a case of scrapie in a bovine is an argument used by advocates of this second theory, although this case may correspond to a completely different neurological disease.[9] Numerous other more or less credible theories regularly enter the debate, with none really emerging.

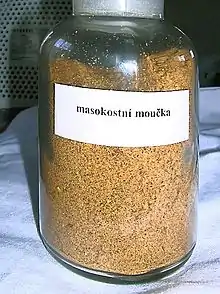

The mad cow disease epidemic certainly has its roots in the recycling of animal cadavers by knackers. Bone and meat parts not used in human food and dead animals collected from farms, which constitute the main waste products of the beef industry, are separated from fats by cooking before being ground into powder.

Before the outbreak of BSE, meat and bone meal was widely used in cattle feed. They are rich in both energy and protein, and are easily digested by ruminants. As a result, they were widely used in cattle, particularly dairy cows.[10] It was the consumption by cattle of meat and bone meal made from calcined tissues from cattle or sheep (depending on the hypothesis adopted), such as brain and spinal cord, and contaminated with the BSE agent, that was responsible for the outbreak of the epidemic.[7]

Initially, the flour manufacturing process used high sterilization temperatures and a fat extraction stage using organic solvents which, without anyone suspecting it, destroyed the prion. But in the mid-1970s, a number of British technicians decided to lower the temperature and drying time of these flours to improve the nutritional quality of the finished product. Due to environmental considerations (hexane discharge into the environment), the solvent fat extraction stage was eliminated in 1981. These changes to the protocol were essentially designed to improve economic profitability, on the one hand by better preserving the proteins contained in the flours, and on the other by reducing the costs of the solvents and energy used, which had risen sharply after the two oil shocks of 1973 and 1979.[11]

In addition, the change in manufacturing process was accelerated by an accident at one of England's main meat and bone meal plants, involving staff handling the solvent: this led to a reinforcement of safety measures, the cost of which was high. This change in practices seems to be at the root of the epidemic. The prion was recycled in meat and bone meal before it was distributed on a large scale in cattle feed, and contaminated animals were, in turn, slaughtered and ground into meal to further amplify the phenomenon.[6]

It is also suspected that there is a mother-calf contamination pathway, which could account for up to 10% of contaminations.[5]

To explain the persistence of the epidemic after drastic measures had been taken, scientists are looking for a possible third route of contamination, which has still not been found. One of the few credible hypotheses is contamination by fodder mites, a phenomenon once observed in scrapie. This hypothesis, like all those involving an external transmission agent, is unlikely, as only the central nervous system is contaminated in cattle, and the prion is not excreted by sick cows. Other hypotheses have suggested contamination through water polluted by knackering plants, or through the soil where meat and bone meal-based fertilizers have been spread, without any tangible evidence.[12]

An epizootic centred on Great Britain

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy first appeared in the UK in November 1986, when the British Central Veterinary Laboratory discovered a cow with atypical neurological symptoms on a farm in Surrey. Examination of the cow's nervous tissue revealed vacuolation of certain neurons, forming lesions characteristic of scrapie. Researchers concluded that a new form of Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) was at work, infecting cattle. The result was bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as "mad cow" disease.

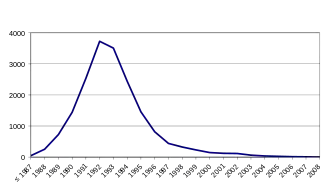

[9]The number of cases, initially low at the end of 1986, increased rapidly. By mid-1988, there were 50 cases a week, rising to 80 cases a week by October of the same year. The weekly rate continues to rise, reaching 200 cases per week at the end of 1989, 300 in 1990, and peaking in 1992 and 1993 with over 700 new cases per week and 37,280 sick animals in 1992 alone. After 1993, the epidemic began to decline rapidly.

However, 20 years on, the disease has still not completely disappeared from the UK: 67 cases were recorded in 2007 and 37 in 2008. In all, no fewer than 184,588 animals contracted the disease in the UK.[13]

The disease was exported from Great Britain from 1989 onwards, when 15 cases occurred in Ireland. Between 1989 and 2004, a total of 4,950 cases were reported outside Great Britain, mainly in continental Europe:

- Israel (one case in 2002) ;

- Canada (four cases, including one in 1993, two in 2003 and one in 2007);

- Japan (13 cases between 2002 and 2004);

- the United States (two cases between 2004 and 2005, and one case in 2006).

Apart from Great Britain, the countries most affected are :

- Ireland (1,488 cases) ;

- Portugal (954 cases) ;

- France (951 cases) ;

- Spain (538 cases) ;

- Switzerland (457 cases);

- Germany (369 cases).

In countries outside the UK, the highest number of cases was recorded in 2001 (1,013 cases) and 2002 (1,005 cases). In total, just over 190,000 animals were affected by the disease in April 2009.[14]

Several hypotheses explain the spread of the disease outside the UK. Firstly, meat and bone meal manufactured in the UK and likely to be contaminated by the prion was exported worldwide. France, Ireland, Belgium, Germany, and later Denmark, Finland, Israel, Indonesia, India and, to a lesser extent, Iceland and Japan, all imported potentially contaminated British meat and bone meal. The export of live animals, possibly healthy carriers of the disease, is also a suspected source of contamination. These animals are then used in the manufacture of local meat and bone meal, generating further contamination.[9]

In Canada, it only took one case in Alberta for the most important customers, the United States and Japan, to take severe boycott measures.

The direct incidence of this disease, despite its spectacular nature and the systematic elimination of any herd where a sick animal is diagnosed, has remained relatively low, since even in Great Britain, it has not exceeded 3% of the herd on an annual basis. The disease mainly affects dairy cows.[8]

Interspecific transmission

In humans

A form of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy specific to humans, known as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), is a degeneration of the central nervous system characterized by the accumulation of a prion. The incubation period lasts years, even decades, before balance and sensitivity disorders appear, followed by dementia. The outcome is systematically fatal within a year or so.

The disease has several causes: most cases are sporadic, as their origin is unknown. There is also hereditary transmission (10 % of cases) and iatrogenic contamination (i.e. due to an operative process) linked to the use of hormones (as in the growth hormone affair in France) or brain tissue transplants (dura mater) from the cadavers of patients, or the use of poorly decontaminated surgical instruments (electrodes).

The deaths of cattle farmers from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease between 1993 and 1995 had first worried scientists about the likelihood of BSE being transmitted to humans, but they concluded that these were sporadic cases with no link to the animal disease.[15]

It was in 1996, when two Britons living north of London died of what appeared at first sight to be Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, that it all really began. Stephen Churchill and Nina Sinnott, aged 19 and 25 respectively, were unusually young to have contracted this disease, which only affects the elderly. That's what pointed researchers in the direction of a new disease, dubbed nvCJD, for "new variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease".

A link was soon suspected between BSE, an animal disease, and new variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a human disease. This link was demonstrated in the laboratory by comparing the amyloid plaques present in the brains of monkeys inoculated with the disease and those of young people who had died of the disease, which proved to be strictly identical. The human form of BSE is broadly similar to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, but differs in a number of clinical and anatomical respects. For example, it affects younger patients (average age 29, versus 65 for the classic disease) and has a relatively longer course (median 14 months, versus 4.5 months).[7] The disease can be transmitted to humans if they consume high-risk tissues (muscle, i.e. meat, is not at risk) derived from contaminated animals.[9]

As of July 2012, the disease has claimed an estimated 224 victims, including 173 in the UK, 27 in France, 5 in Spain, 4 in Ireland, 3 in the US, 3 in the Netherlands and 2 in Portugal. Japan, Saudi Arabia, Canada and Italy each had 1 case.[16]

Other domestic animals

When the disease first appeared, it was often thought to have originated in sheep, because of its similarity to scrapie. Today, this hypothesis has lost some of its credibility. However, while the exact origin of the disease is unknown, it is certain that it has a strong propensity to cross the species barrier. As early as May 1990, the epidemic spread to felids, with the death of a domestic cat victim of the disease, probably contaminated by food, as cat food is very often made from bovine offal.

In March 2005, the French Food Safety Agency (AFSSA by its acronym in French) published an opinion definitively confirming the risk of BSE in small ruminants (goats and sheep). In these two species, the risk of transmission to humans may be higher, since, in addition to meat, milk may also be contaminated.

AFSSA considers the precautionary measures taken to be inadequate: milk from suspect herds is not tested, and only some of the cadavers of suspect animals are subjected to prion research.

History

Meat and bone meal has been used in cattle feed since the late 19th century. In the eyes of breeders, it does not seem unnatural, since cows are opportunistic carnivores: they spontaneously consume the placenta of their newborns, eat earthworms and insects present in the fodder they ingest, or the cadavers of small rodents or fledglings. The practice of feeding them these protein-rich "food supplements" developed particularly during the World War II in Britain, which was then short of plant resources, and intensified in the 1950s, with the development of intensive farming aimed at maximum productivity.[17]

1985–1996: a long period of latency

It all began in September 1985, when the veterinary laboratory of the British Secretary of State for Agriculture reported the appearance of a new disease with strange symptoms in British cattle. It wasn't until November 1986 that the new disease was identified as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). The following year, it was discovered that the disease was caused by the incorporation of meat and bone meal into ruminant feed.[18]

From 1988 onwards, BSE became notifiable in Great Britain, and all BSE-infected cattle had to be slaughtered and destroyed as a preventive measure. The British authorities banned the feeding of meat and bone meal to cattle. In 1989, France decided to ban imports of British meat and bone meal. The British government took further measures, banning the consumption of certain offal (brain, intestine, spinal cord, etc.).[18] The European Community banned the export of British cows over one year old or suspected of having BSE.

In 1990, the same European Community ruled that BSE-infected animals were not dangerous to human health. Imports of British meat were allowed to resume, a situation denounced by France, which continued to take increasingly strict measures, imposing compulsory declaration of BSE-infected cattle and banning the use of meat and bone meal in cattle feed. All this did not prevent the discovery of the country's first case of mad cow disease in 1991, in the Côtes d'Armor region.[18] The government ordered the slaughter of the entire herd if any animal was affected.

In 1992, the European Community instituted the "Herod Premium" (an allusion to the Roman governor of Judea who was responsible for slaughtering all newborns at the time of Christ's birth) to compensate for the slaughter of calves from birth, to combat the overproduction of "milk meat", i.e. calves that induce lactation in dairy cows, their cadavers being used in the pet-food industry.[19] Researchers discover the possibility of BSE transmission to other species.

- 1993: The disease peaks in the UK in 1993, with almost 800 cases per week. British farmers in contact with BSE-infected cows die of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

- 1994: the European Union bans the use of proteins derived from bovine tissue in ruminant feed, and the export of beef from farms where a case of BSE has occurred.

- 1995: several British farmers fall victim to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. A new form of the disease appears in Great Britain and Germany. The media announce the possible transmission of BSE to humans.

1996: the crisis erupts

- 1996: after France and other countries, the European Union imposes an embargo on all cattle and cattle products from the UK. The beef market plummets. Several European countries introduce a national meat identification system.

- 1997: the European Union decides to partially lift the ban on British beef exports, which member countries consider premature.

- 1998: creation in France of the Comité national de sécurité sanitaire (CNSS), the Institut de veille sanitaire (InVS) and the Agence française de sécurité sanitaire des aliments (AFSSA).

- 1999: France refuses to lift the embargo, contrary to the decision of the European Commission. Debate surrounding the precautionary principle.

- 2000: the European Union announces the launch of a rapid BSE diagnostic test program. In France, Carrefour supermarkets ask their customers to return any beef purchased from their shelves suspected of coming from BSE-infected animals.

The French government suspends the use of meat and bone meal in feed for pigs, poultry, fish and domestic animals. Nature magazine publishes a British study estimating that 7,300 BSE-contaminated animals have entered the food chain in France since 1987. Another mad cow crisis.

A second crisis broke out in France in October 2000, when a suspect animal was arrested at the entrance to the SOVIBA slaughterhouse. Meat from animals from the same herd slaughtered the previous week[20] was immediately recalled by the retailer Carrefour, applying, in its own words, an "extreme precautionary principle". Once again, the media picked up on the story and the crisis escalated.[21] On 5 November 2000, during a special evening entitled Vache folle, la grande peur, M6 broadcast a lengthy investigation entitled Du poison dans votre assiette, by Jean-Baptiste Gallot and produced by Tony Comiti,[22] featuring the testimony of a family whose son has the human form of mad cow disease.[23] This high-profile documentary provoked a solemn television address by French President Jacques Chirac[24] on 7 November 2000, calling on the Socialist government to ban meat and bone meal.[25]

- 2002: France announces that it is lifting the ban on British beef.

Deep socio-economic crisis

Social crisis

As soon as the media got hold of the affair and the public discovered the problem, a violent crisis erupted. The main feature of this crisis was the obvious discrepancy between consumers' expectations and farmers' practices. The public discovered that cows not only ate grass and plants, but also mineral, synthetic and animal feed supplements. As a result, the public applied the precautionary principle on its own scale, leading to a fall in beef consumption and the transition from a social to an economic crisis. Prophylactic measures taken by the authorities, such as the slaughter of entire herds, far from reassuring, contributed to the anxiety, while exhortations by political leaders to keep their cool and not deprive themselves of meat had no effect.

The disease is also worrying because it is not localized, like some other contemporary crises, and is transmitted by an apparently innocuous act: eating beef.[26]

Role of the media

The media played an important role in triggering this social crisis. Since the end of 1995, the growing number of unexplained cases of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease had prompted scientists to ask questions and the British public to express growing concern. The press relayed this information, warning against eating beef, and clearly demonstrating a desire to break the silence surrounding the issue. With this in mind, the Mirror of 20 March 1996 announced the official statement to be made that evening by Stephen Dorell, the Secretary of State, on the potential link between BSE and CJD. This really launched the crisis. In the spring of 1996, BSE was regularly mentioned in the first half of TV news programmes, and made headlines in magazines: "Alimentation: tous les dangers cachés" (L'Événement, April 1996); "Alerte à la bouffe folle" (Le Nouvel Observateur, April 1996); "Peut-on encore manger de la viande?" (60 millions de consommateurs, May 1996); "Jusqu'où ira le poison anglais?" (La Vie, June 1996); "Vaches folles: la part des risques, la part des imprudences" (Le Point, June 1996).[21]

Some of the media have been criticized (which ones?) for a lack (of what?) of coverage of events.[27] However, the media's grip on consumers would probably not have been so strong had it not been for the crisis of confidence that arose between consumers and public authorities during the crisis.[28]

Consequences for meat consumption

From the first stirrings of the disease in the UK, it was in Germany that consumers reacted first, limiting their beef consumption by 11% in 1995.[15] The UK also saw an early drop in consumption, which by December 1995 was between 15% and 25% lower than the previous year. Particularly after the crisis broke out in earnest at the end of March 1996, consumers began to buy less beef as a precaution, causing the market to plummet. Whereas in 1995, per capita consumption of beef in France stood at 27.7 kilos, purchases fell by around 15% in 1996, reaching 25% (45% for offal) following the announcement of the transmissibility of BSE to other species. Poultry meats benefited from the crisis, recording increases of 25% for chicken and up to 33% for guinea fowl. Most other European countries experienced similar declines, such as Germany, where beef consumption, already hit, fell by 32% between April 1995 and April 1996. At the same time, consumption was down 36% in Italy.[29]

Charcuterie producers who had been using bovine intestines found various alternatives: synthetic casings, from other species such as pork, mutton or horse, or from cattle imported from disease-free countries.[30]

Support for the industry

The crisis in domestic consumption, coupled with the virtual halt in exports, has seriously affected the entire French beef industry. Farmers saw prices for young cattle fall sharply from March 1996, notably due to the halt in exports, which had been their main outlet. Prices recovered slightly from July onwards. Cow prices were less affected. Supply was limited by the British embargo and the possibility for farmers to keep their animals on the farm. After collapsing in April, the price of grazers recovered in May thanks to the intervention of the European Commission, which decided to take 70,000 tonnes of grazer cadavers (around 300,000 animals) in August to support prices.[31][32]

In view of the scale of the crisis for the industry, the French government has taken a number of measures to support its players and get them through this difficult period. Beef industry professionals (traders, slaughterers, trimmers, cutting plants) benefited from deferral of social security contributions and tax deductions. Subsidized loans at a rate of 2.5% per year were granted to downstream companies. In addition, a restructuring and conversion fund has been set up for the tripe industry and small and medium-sized enterprises upstream of final distribution. Endowed with a €9 million credit and managed by OFIVAL (Office national interprofessionnel des viandes, de l'élevage et de l'aviculture by its extension in French), this fund has supported the regrouping of businesses, the conversion of some of them, and even the cessation of activity in certain difficult cases.

Following the decision of the European Council in Florence on 25 June 1996, France obtained a €215 million package of Community funds to help its livestock farmers, enabling an increase in premiums for male cattle and the maintenance of suckler cow herds. Additional premiums were distributed at departmental level, and farmers' cash flow was eased by the assumption of interest and deferral of social security contributions and reimbursements.[6]

Impact of embargoes

Trade embargoes have had a major impact on the countries concerned. First and foremost, the United Kingdom suffered from the embargo imposed on it by the European countries to which it exported large quantities of beef. The cessation of these exports, as well as of derived products, coupled with a fall in domestic consumption, led to an unprecedented crisis in the British beef industry.[29] Embargoes have also been imposed in other countries around the world. A single case in the United States in 2003 was enough for most Asian countries, notably Japan (one third of American exports[33]), to take immediate trade measures against American beef.

In all, 65 nations halted their imports of American meat, denouncing the inadequacies of the American control system. As a result, US exports plummeted from 1,300,000 tonnes in 2003 to 322,000 tonnes in 2004, after a case of mad cow disease was identified. They have since recovered, reaching 771,000 tonnes in 2007.[34]

Ethical crisis and philosophical critique

In her book Sans offenser le genre humain, réflexions sur la cause animale, philosopher Elisabeth de Fontenay considers this crisis to be above all ethical, revealing a "forgetfulness of the animal":

"The slaughter campaigns, motivated by the fear of epizootics, and particularly bovine spongiform encephalitis, caused by herbivores eating meat and bone meal, were elegantly popularized under the name of "mad cow crisis": no doubt so as not to have to refer to the madmen we now are. In these diseases, which are transmitted to humans under the names Creutzfeldt-Jakob and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, contagion breaks down the interspecific barrier (...) Is it really a sign of unbridled anti-humanism to be shocked by the exclusive insistence of leaders and the media on public health problems, and by the casualness they display in the face of the cruel and absurd fate of these animals, destroyed and burned en masse at the stake? We are too often besieged by images and complacent designs of cattle struck by erratic behaviors that are laughed at." – Elisabeth de Fontenay, Sans offenser le genre humain. Réflexions sur la cause animale.[35]

Finally, for Elisabeth de Fontenay, it is the very origin of the process that reveals her categorical disregard for animals for strictly financial values:

"Industrial slaughter has already turned administered killing into a purely technical act. But the absurdity of its profitability calculations comes to the fore when animals are slaughtered for nothing: so that we don't eat animals that may or may not be affected by a disease such as epizooty, untreated but slaughtered for the "lowest cost", and even if the disease is not transmissible to humans, such as foot-and-mouth disease. This productivist, technical and mercantile civilization, (...) oblivious to the amphibology of the word 'culture', oblivious to the living being that is the animal, could only make possible, if not necessary, these bloody exhibitions." – Elisabeth de Fontenay, Sans offenser le genre humain. Réflexions sur la cause animale.[35]

In India

In India, the original land of Hinduism, where the cow is seen as a mother who gives its milk to all, and holds a special place in the hearts of Hindus, being the symbol of the sacredness of all creatures[36] and the incarnation of all deities, reactions to the West were overwhelmingly negative. Numerous Hindu associations declared that the West had been punished with the appearance of sick humans for its zoophagy, or meat-eating.[37]

Acharya Giriraj Kishore, leader of a prominent Hindu group, was quick to declare that human non-vegetarianism would continue to incur the wrath of the gods,[37] and that Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease was a warning from God to the world to be vegetarian, and a symbol of divine impartiality:

"I feel that the West has been punished by God because of its habitual violence of killing [animals]."[37]

In Hinduism, diseases are actually defeated and/or propagated by deities, such as the goddess Mariamman or Shitala Devi.

Measures implemented

There is no cure for mad cow disease. The means used to curb the epizootic therefore consist exclusively of preventive measures, all the more stringent since we know that human health is at stake. In 1988, the British government set up the Spongiform Encephalopthy Advisory Committee (SEAC), headed by Professor Richard Southwood, to learn more about the disease and take appropriate measures. This advisory committee subsequently played a major role in the various measures taken in the UK to curb the disease.[9]

Ban on meat and bone meal

As early as July 1988, the UK took the decision to ban the use of animal proteins in cattle feed, quickly followed by the other countries concerned, such as France in 1990. In 1991, the UK banned the use of meat and bone meal in fertilizers; in 1994, France extended the ban to other ruminants; in October 1990, France banned the use of high-risk materials (brains, spinal cord, etc.) in the manufacture of meat and bone meal (June 1996); and in August 1996, France banned the consumption of meat and bone meal by other species (November 2000).[38]

Despite all these precautions, new cases continue to be discovered, even in animals born after these measures were taken. In 2004, the UK recorded 816 affected animals born after the 1990 ban, and 95 cases in animals born after the 1996 complete ban.[39]

Similarly, in France, 752 cases of BSE were discovered in animals born after the introduction of the ban on meat and bone meal in cattle feed in 1990. These cases, known as NAIF (born after the ban on meat and bone meal), raised questions about compliance with the rules and the existence of a possible third route of contamination.

In-depth investigations carried out by the Veterinary and Health Investigation Brigade (Direction Générale de l'Alimentation, DGAL by its acronym in French) eventually revealed that cattle feed could be contaminated by feed intended for monogastric animals for which meat and bone meal was still authorized. Cross-contamination could have occurred during the manufacture of these feeds in the factory, but also during transport or even on the farm. Despite the reinforcement of measures in June 1996, a few cases appeared in animals born after this date, known as super NAIF. These can be explained by the importation into France of meat and bone meal from countries which believed themselves immune to the disease, even though they were already contaminated, or by the use of animal fats in feed or milk replacers until 2000.[40]

The UK can be blamed for having continued and even increased exports of its meat and bone meal worldwide after the 1988 ban on its distribution to ruminants. In 1989, France imported 16,000 tonnes of meat and bone meal likely to be contaminated with BSE, before such imports were banned by the French government. Although from 1990 onwards, risk materials were removed from the manufacture of English meal, it still carried a risk. "All these exports, maintained for economic reasons, are probably responsible for the spread of the disease throughout the world".[9]

Since 2008, Brussels has been considering, under pressure from livestock farmers and the industry, the reintroduction of flours produced not from ruminant by-products, but from the remains of pigs, poultry and fish, under certain conditions, following the rise in feed prices (150% increase for wheat, 100% for soya): According to Nicolas Douzin, Director of the Fédération nationale (France) de l'industrie et du commerce en gros des viandes, "These would be proteins extracted exclusively from unusable cuts, but suitable for human consumption".[41]

Withdrawal of certain products from consumption

From 1989, certain bovine tissues and organs considered dangerous to humans were banned from sale in the UK on the advice of the Southwood Committee. They are removed at the abattoir (only the vertebral column may be removed at the cutting plant or butchery) before being incinerated. Originally, the products concerned were the vertebral column, brain, eyes, tonsils, spinal cord and spleen.[42] This decision was extended to Northern Ireland and Scotland on 30 January 1990, and various European countries adopted similar decisions, including France in 1996. As with meat and bone meal, it is regrettable that the UK continued to export its high-risk offal between the date of the ban and the embargo imposed on its products by France, followed by the European Union, in early 1990.[9]

Over time, the list of products banned for consumption has been revised and extended several times as knowledge has advanced. Thus, in June 2000, ileum was added to the list of products banned in France, followed in October 2000 by the rest of the intestines, then in November by thymus, or sweetbreads. These were used in particular to coat certain charcuterie products such as andouilles, andouillettes, cervelas and saucissons, and carried risks due to the presence of lymphoid tissue that could be contaminated by BSE.[30] Improved knowledge also made it possible to set a more precise age limit. In September 1996, France decided to remove the central nervous system only from cattle over 6 months of age, and then from cattle over 12 months of age from 2000 onwards, since this part of the body only becomes contaminated after a slow progression of the disease. At the same time, all age conditions were removed for the removal of the spleen, tonsils, thymus and intestine, which can be infected at an early stage. In 1996, the legislation was extended to sheep and goats, which are susceptible to contracting the disease.[9]

In April 1996, following the appearance of the human variant of the disease, the British government decided to ban the consumption of meat from cattle aged over 30 months.[9]

Animal fats were authorized for human consumption, provided they were treated by ultrafiltration and sterilization at 133 °C for 20 minutes.[42]

Embargo on British meat

After a long period of hesitation, in 1996 the European Community declared an embargo on meat from Great Britain. This ban was extended to other animal products such as tallow and gelatin. In 1999, the European Union lifted the ban on meat under certain conditions: for example, boneless meat from cattle raised on BSE-free farms and less than 30 months old at the time of slaughter was accepted.[7]

Despite this embargo, British meat continues to be exported to Europe, mainly due to inadequate controls by the British government. In 1999, the European Commission imposed a financial penalty of 32.7 million euros on the UK for its control failures.[9]

However, one country maintained the block on British meat: France, motivated by studies carried out by the AFSSA, which considered that the guarantees offered by the UK were insufficient. The British were quick to express their dissatisfaction, and responded by refusing various French products. Faced with France's stubborn adoption of the precautionary principle, the case reached the European Court of Justice. In December 2001, the Court ruled that the blame was shared: France should have expressed its disagreement earlier, but the measures taken by the European Commission did not, at the time, guarantee sufficient traceability of British products.[43] Finally, in September 2002, France lifted its embargo following a positive opinion from AFSSA .

Screening for BSE in cattle abattoirs

The UK and France have sometimes employed different tactics to bring the epizootic under control. In the UK, for example, where BSE has been notifiable since June 1988, the government has decided to ban the consumption of animals aged over 30 months, the age at which the disease develops. As a result, there is no need to screen animals at the slaughterhouse, as the animals consumed are not old enough to have developed the disease, and are therefore undoubtedly healthy.

France, on the other hand, has opted for systematic testing of animals slaughtered at over 48 months of age, the earliest age at which the disease can be detected. Detection of the disease in tissues precedes the first clinical symptoms by 6 months, and is complementary to simple clinical monitoring of animals.[38] However, clinical surveillance remains compulsory for all cattle entering the slaughterhouse, and was even reinforced in 2000 with the recruitment and assignment of additional veterinary staff to slaughterhouses.[6]

In cattle slaughterhouses, BSE cases are detected by sampling the obex, a small V-shaped piece of the medulla oblongata hidden by the bovine cerebellum. The sample is then analyzed in the laboratory using an ELISA-type immunological test. The laboratory takes the right-hand part of the V, which is used for the rapid test.[44]

As of 28 November 2010, of the 1,365,561 cattle slaughtered in France since 1 January 2010, only one has tested positive for BSE. The number of BSE cases reported following slaughterhouse testing has been minimal over the past 5 years, in line with the natural prevalence of the disease: 2 cases in 2006, i.e. 0.0008 cases per thousand cattle slaughtered; 3 cases in 2007 (0.0013 %0); 1 case in 2008 (0.0004 %0) and 2 cases in 2009 (0.0013 %0), with testing alone costing the industry over 40 million Euros a year to dispose of an animal whose consumption would have presented no risk in any case, as the organs at risk or specified risk materials (SRMs) are destroyed anyway.

Once the results are known, cadavers likely to be contaminated by the prion (the test may prove positive on the first occasion, but false-positive cases may also exist) are removed from the human and animal food chain, along with by-products (offal, tallow, leather, etc.). In France, a second confirmation test is carried out in a specialized laboratory in Lyon, using the remaining part of the obex. This second test can be read after one week. However, as cattle cadavers cannot be kept in refrigerators for this length of time for hygiene reasons, the cadavers are destroyed before the results are available. Organs at risk or specified risk material (SRM) are recovered for destruction (spinal cord, intestines, brain and eyes). The destruction of the cadavers is paid for by the inter-professional organization, but the loss of income linked to the destruction of SRM is considerable for the abattoir (around €600 per tonne).

Calves are not tested for BSE, but certain high-risk organs are destroyed (intestines). To limit the spread of the disease, several countries have decided to systematically slaughter herds in which an animal is affected.

Animal slaughter

While little is known about how the disease is transmitted, the main prophylactic measure adopted when an animal is likely to be a carrier of the disease is slaughter.

The slaughter campaign was particularly impressive in the UK. Following a ban on the consumption of cattle over 30 months of age (the age at which animals are likely to develop the disease), the British government launched a program to slaughter these animals (with the exception of breeding stock, of course) and compensate farmers. By the end of 1998, over 2.4 million cattle had been slaughtered in the UK. In August 1996, the UK decided to improve the identification of cattle born after 1 July 1996, by introducing a passport system that would enable the selective slaughter of the offspring of BSE-infected animals.[9]

In France, the tactic of diagnosing animals over 24 months of age on a case-by-case basis prevented a slaughter on such a scale. But culls were still common. Indeed, any case detected in a slaughterhouse and confirmed in Lyon must be quickly followed up by a search for the animal's farm of origin, made possible by the traceability of these animals. The herd of origin, as well as those of any farms where the animal may have been present, are then slaughtered in their entirety. The farmers concerned receive compensation from the State.

The practice of systematic slaughter was developed at a time when little was known about the disease and how it was transmitted within a herd, and is the one used for highly contagious diseases, which is not the case with BSE. Its sole advantage was to reassure the consumer with its radical and impressive appearance, but it caused great harm to breeders, who sometimes took a very long time to build up their herd's genetics, and proved to be costly.[43] It was subsequently called into question, notably in Switzerland where it was replaced by selective slaughter in 1999, then in France under pressure from the Confédération Paysanne, which obtained an initial reform in early 2002. From that date onwards, in the event of an outbreak of BSE on a farm, animals born after 1 January 2002 are spared. Since December 2002, systematic slaughter has been replaced by more selective slaughter: only animals of the same age as the sick cattle are slaughtered.[33] These measures are still applicable in 2009, but the disease has virtually disappeared and they no longer need to be applied.

Improved traceability of beef products

Traceability is the ability to trace the origin of a piece of meat to pursue two objectives: on the one hand, the prevention of food risks (possibility of withdrawing from sale batches of meat suspected a posteriori of presenting a risk to the consumer), and on the other hand, consumer information (indication of the exact origin of products purchased).[9]

In the wake of the mad cow crisis, measures taken at European level concerning animal identification and traceability have enabled the industry to significantly improve practices in this area. In France, buckles have been compulsory since 1978, and since 1997 must be attached to each ear within 48 hours of birth. Within a week of birth, the farmer must report the birth of the calf, its racial type and the identity of its dam to the local livestock establishment (établissement départemental de l'élevage, EDE by its acronym in French). Traceability is particularly new in cutting plants and slaughterhouses. All intermediaries in the beef chain must be able to track products so that they can trace the animal to which each final product belongs. As a result, since 1999, cadavers, half-cadavers, quarters and bone-in wholesale cuts have had to bear the slaughterhouse slaughterhouse number in edible ink. Product labelling regulations have also been tightened up. Since 2000, beef labels in Europe have been required to show a reference number or code linking the product to the animal from which it is derived, the country of slaughter and the approval number of the slaughterhouse, and the country of cutting and the approval number of the cutting plant.[9]

When it comes to traceability, France is ahead of Europe overall, with even more stringent legislation. As early as 1996, with a view to reassuring consumers, the national interprofessional livestock and meat association (Interbev), with the support of the Ministry of Agriculture, created the VBF (viande bovine française, by its extension in French) collective mark, indicating that an animal was born, raised and slaughtered in France. Then, in 1997, France made it compulsory for labels to indicate the animal's origin, racial type (dairy, beef or mixed breed) and category (bull, ox, young bovine, heifer, cow).[45]

Other precautions

On 20 October 2000, the British government decided to withdraw a polio vaccine made from cattle tissue that could be contaminated with BSE. This product, called Medeva and distributed to thousands of children, could present risks of transmission of the new variant of Creutzfeld-Jakob disease.[46]

Blood transfusions are also suspected of allowing transmission of the disease. For this reason, in August 1999, Canada decided to exclude from donating blood anyone who had spent six months or more in the UK between 1980 and 1996, and in August 2000 extended this decision to residents of France over the same period. The United States is taking similar measures. For its part, France bans from donating blood anyone who lived in the UK for 6 months or more during the mad cow disease period (1980–1996). These fears were based on experiments carried out on sheep which demonstrated that the disease could be transmitted by blood transfusion,[47] and were then largely confirmed by the publication in 2004 and 2006 of studies on three English patients who died of the new variant of CJD after receiving transfusions from people who had themselves developed the disease after donating blood.[48]

The cost of measures

BSE control measures have a significant cost, which is borne by both consumers and the State. The three main areas of expenditure are prevention, detection and eradication. Preventive measures involve removing specified risk materials (SRMs), disposing of waste through the low-risk circuit, and collecting and destroying SRMs and cadavers through the high-risk circuit. These measures represent a cost of 560 million euros per year, or 67% of the total cost of control. Surveillance measures generate costs through the training of network members in clinical case detection, administrative processing of suspected cases, visits and, to a lesser extent, compensation for farmers. The total annual cost of surveillance measures amounts to 185 million euros, or 21.5% of the total cost of BSE control measures. Finally, the systematic slaughter of herds in which a case of BSE has been identified represents 12.5% of the total cost of control measures, i.e. 105 million euros. This brings the total annual cost of BSE control measures in France during the crisis period to 850 million euros.[6]

In the UK, the costs incurred by the epizootic are impressive. Between 1986 and 1996, the British government allocated £288 million of public money to research and compensation plans for the industry.[49]

Consequences for the industry

Background

The use of meat and bone meal in livestock feed is nothing new. They have been used in the USA since the end of the 19th century, and arrived in France at the beginning of the 20th, but it was only in the second half of the 20th century, and particularly in the 1970s, that their use became more widespread. They have the advantage of being protein-rich, with little degradation by ruminant rumen microorganisms. They therefore provide essential amino acids (lysine and methionine), which are a useful supplement for high-producing dairy cows. They also provide large quantities of phosphorus and calcium. This nutritional benefit alone is not enough to justify the use of meat and bone meal in feed. Alternative solutions exist, such as soy and rapeseed meals, which can be tanned to prevent their proteins from being degraded by rumen micro-organisms. Animal meal was also an inexpensive ingredient in feed, and made it possible to "recycle" certain livestock waste products.

But the main benefit of meat and bone meal for European livestock farmers was to compensate for their large deficit in oil-protein crops such as soya, sunflower and rapeseed, which are essential for providing animals with the quantities of protein they need to develop properly. These plants are rarely grown in Europe, which is largely dependent on producers in South America and the United States. This dependence increased in the second half of the 20th century with the development of livestock farming and world trade agreements, which enabled Europeans to support their grain financially in return for opening their borders to foreign oilseeds and protein crops.[9]

However, the use of meal in livestock feed needs to be put into perspective. They have never been a major source of feed for ruminants, and their concentration has never exceeded 2–3% in industrial mixes distributed to ruminants, i.e. less than 1% of the total ration.[43] They were mainly intended for dairy cows, and were not used by all feed producers. In France, their use was mitigated by the use of oilcake tanned using a process patented by INRA, which was not available in other European countries such as the UK.[9]

Adapting feed to new regulations

Following the mad cow crisis, the incorporation of meat and bone meal (with the exception of fish meal and derivatives under certain conditions) and the majority of animal fats into animal feed was banned. This has led to major changes in the feeding practices of European livestock farmers. Stopping the use of animal fats had repercussions on the technological quality of concentrated feeds. Animal fats acted as binders for pellets, and their absence increased their friability, as well as altering other physical characteristics such as hardness and color. This in turn affected the palatability of the feed, and hence the feeding behavior of the animals.

These animal fats have generally been replaced by vegetable fats such as palm oil and rapeseed oil. Most often unsaturated, they can lead to defects in cadaver presentation and poorer preservation of animal products, whose fat is more sensitive to oxidation. What's more, these vegetable fats are less effective for pelletizing concentrated feeds. Soya, and to a lesser extent rapeseed and corn gluten, are used to replace the protein content of flour. About 95% of these products come from South America and the United States, and their importation once again places European countries in a situation of heavy dependence. What's more, they may come from genetically modified plants, common in these parts of the world, fuelling controversy over the use of GMOs in animal and human nutrition.[6]

What happens to meat and bone meal?

Every year, France produces around 600,000 tonnes of meat and bone meal, as well as 160,000 tonnes of meal from poultry offal and feather powder. Worldwide, almost five million tonnes are produced annually: 2.3 million tonnes by Europe, and the rest by the United States. Since the total ban on the use of meat and bone meal in pet food, alternative solutions have had to be found to get rid of it. Initially, they were used to feed other farm animals. In 2000, 75 % of French meal was used in poultry feed, and 17 % in pig feed.[9] But this solution proved unsustainable, as the ban was extended to other species. Today, the preferred solution is incineration. Cement manufacturers would use the majority of this meal for energy production, while incineration plants and the thermal power stations of Électricité de France would take care of the rest.[10]

Removal of risk materials

Slaughterhouses had to adapt to the new regulations to collect the various risk materials. In particular, they had to purchase the equipment needed to aspirate spinal cord. Cutting practices have been modified by the ban on the sale of meat adjoining a part of the spinal column, which has led to new practices in the cutting of prime rib and T-bone steak. In addition, it has become compulsory to sort bones intended for gelatin production, which must not include vertebrae. Fat destined for tallow production must be removed before the cadaver is split, to ensure that no bone splinters from the vertebral column are present. Finally, these materials are collected in sealed bins, where they are denatured by dyes such as methylene blue or tartrazine. They are then separated from recoverable waste, before being collected by the public knackering service.[9] All this generates additional costs for processing cadavers, as well as a loss of income for slaughterhouses, which can no longer recycle certain products.[49]

Changes in practices

The practice of "juggling", which consisted in inserting a flexible metal rod (the juggling rod) into the spinal canal, through the orifice resulting from the use of the slaughter gun, to destroy the medulla oblongata and the upper part of the spinal cord, and which was intended to protect personnel against sudden agonic movements of the limbs of slaughtered animals, was banned in 2000. AFSSA considered that this technique risked dispersing contaminating material into the cadaver.[15]

The "knacker- tax" affair in France

In France, knackering (including the removal of dead animals from farms and slaughterhouses that are unfit for consumption and must be disposed of as quickly as possible to eliminate any source of infection) is a public service. Highly costly, it has long been a financial problem.

The mad cow crisis exploded the system. Until then, it had been possible to recycle some of the products of cadaver treatment, but after much vacillation, it was decided to destroy everything, with two cumulative effects: loss of direct income, and an increase in the volumes to be destroyed, and therefore in costs. The cost of destroying the stocks of meal and fat built up before the change in legislation requiring the removal of cadavers, slaughterhouse seizures and the central nervous system from the manufacture of meat and bone meal is estimated at 130 million francs.

In addition, the failure to recycle cadavers (250,000 tonnes per year) and slaughterhouse waste (50,000 tonnes per year) results in a loss of revenue of 350 to 400 million euros per year.[29] Added to this, initially, was a stock problem, due to the time lag between the decision to destroy everything (and thus ban its use) and the implementation of a destruction solution (which will be found with cement manufacturers, whose energy-intensive furnaces are not demanding in terms of fuel type).

According to the logic of public service and the polluter-pays principle, it is the beneficiaries (breeders and slaughterhouses) who should have borne the financial burden of the problem (along the lines of the household waste tax, for example). However, in the context of crisis and already depleted revenues, this solution did not seem politically acceptable. In 1996, it was decided that meat retail would be taxed.[50] The major operators immediately took the dispute to the European Union, where the tax rate increased fivefold to over 3% in 2000. In 2003, the European Court of Justice condemned the tax as distorting competition due to its inappropriate tax base. Immediately, tax inspection brigades tried to dissect the accounts of a handful of hypermarkets to establish that the amount had indeed been passed on to customers, without any useful success (not least because this increase in unit prices resulted in a loss of sales volume, and it is impossible to retrospectively reconstitute the gains made by retailers had the tax not been levied). The sums paid therefore had to be reimbursed to the distributors, with interest on arrears of 11 to 12%.

Henceforth, the "slaughter tax", paid by slaughterhouses, is the only one in force, as it respects the "polluter pays" principle.

Political responsibility for the crisis

Withholding information

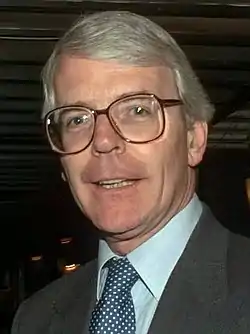

The United Kingdom, governed at the time by Prime Minister John Major, was accused of misleading other countries by withholding information. At the time of the ban on the use of meat and bone meal in ruminant feed, the British government never informed the European Commission and other member states of its decision and of the suspicions surrounding the use of meat and bone meal, even though exports to other countries were increasing.[51]

Insufficient controls

The British government is suspected of not having taken all the necessary precautions following the ban on meat and bone meal in ruminant feed, not only by overlooking cross-contamination but also by failing to provide the controls and sanctions required for the effective application of the measures taken. The report of the European Parliament's Temporary Committee of Inquiry into the BSE crisis in February 1997 underlined the British government's heavy responsibility for the spread of the disease.[9]

Slow decision-making in France

France has often lagged behind the UK in decision-making. For example, the decision to halt the introduction of meat and bone meal in cattle feed was taken two years after the UK, and concerned only cattle until 1994, when it was extended to all ruminants. Similarly, while the French government was quick to ban the import of risk materials from the UK only three months after their consumption had been banned there, the decision to completely remove all risk materials from human foodstuffs was taken in 1996, six years after the UK decision, even though this seemed to be the measure that would ensure the greatest safety for the consumer.[9]

Although France has generally been ahead of European regulations, it has sometimes been slow to implement European Directives on certain subjects. A case in point was the modification of legislation concerning the processing of meat and bone meal to require it to be heated to 133 °C for 20 minutes under 3 bars of pressure, the conditions required to destroy the prion. This new regulation, contained in a 1996 European directive, was not applied in France until two years later.[9]

Red tape

A number of critics link the European Union's policy to the mad cow crisis, in particular its inertia. Throughout the crisis, it lagged behind the measures taken by the UK and then France. We had to wait six years after the ban on meat and bone meal in cattle feed for the EU to prohibit exports to other member states. Similarly, the European ban on the use of risk materials in the food chain only came into force in 2000, after three years of proceedings, and that on the distribution of meat and bone meal to farm animals in 2001.

This delay was due not only to the European authorities, but also to the refusal of certain member states to take action, as they did not feel concerned by BSE. The situation changed with the discovery of BSE cases in Germany and Denmark in 2000, which led to major measures being taken from that date onwards. Europe is also criticized for its lack of severity in the face of such a crisis, which can be seen in its less stringent regulations than those of certain member countries, and its derogations such as those concerning the compulsory removal of the vertebral column after 30 months in the UK and Portugal, compared with 12 months elsewhere, even though these countries are among those most affected by the disease.[9]

Another criticism levelled at Europe at the time was the lack of importance it attached to human health. Until 1994, only the Ministers of Agriculture discussed the subject of agriculture. At the time, however, Europe had no competence in the field of human health. After the crisis, the Amsterdam Treaty of 1999 gave the Community wider prerogatives in this area. Moreover, the notion of the precautionary principle did not appear in European texts. Here again, BSE changed things, with the European Court of Justice recognizing the notion of the precautionary principle when human health was at stake from 1998 onwards. In fact, it wasn't until there was evidence that the disease was transmissible to humans that the Commission took the situation a little more seriously. Before 1996, the advisory committees were under pressure to avoid alarmism in their conclusions, and the disease was neglected, as attested by a handwritten note from Mr. Legras, reproducing the instructions given by Commissioner Ray Mac Sharry and made public by the press, which includes the phrase "BSE: stop any meeting".[9]

Conflicting situations

The application of stricter legislation in certain Member States than that adopted by the European Union has led to conflict situations, particularly in the context of trade in meat and live animals. Indeed, these products fall within the exclusive competence of the Community, and any hindrance to such trade is formally prohibited by European institutions. Yet, as the epidemic gained momentum in the UK, the European Commission hesitated to take action, mainly to preserve free movement and the single market it was in the process of finalizing. When certain countries imposed an embargo on British meat in 1990, the Commission lobbied to abort the initiative, threatening to take the matter to the European Court of Justice. The countries concerned finally gave in, convinced by the measures taken by the British government, which were unfortunately not followed up seriously.

Similarly, in February 1996, German Länder closed their borders to British beef and saw the European Commission initiate new proceedings against Germany. A month later, 13 Member States followed the position taken by these Länder, although no European measures had yet been taken. Again, at the end of 1999, France and Germany refused to lift the embargo as recommended by the Commission. France should have expressed its disagreement earlier, but it is true that the measures taken by the European Commission did not, at the time, guarantee sufficient traceability of British products.[9]

See also

References

- Benkimoun, Paul (24 January 2017). "Un cas atypique de variant de la maladie de Creutzfeldt-Jakob". lemonde.fr (in French).

- "Un cas de vache folle confirmé dans les Ardennes". liberation.fr (in French). 2016.

- Lantier, F. (2004). "Le diagnostic des encéphalopathies spongiformes chez les ruminants". Productions Animales, INRA (in French). 17: 79–86. doi:10.20870/productions-animales.2004.17.HS.3632.

- Kilani, Mondher (2002). "Crise de la « vache folle » et déclin de la raison sacrificielle*". Terrain (in French) (38): 113–126. doi:10.4000/terrain.1955. ISSN 0760-5668. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- Institut de l’Élevage (2000). Maladies des bovins : manuel pratique (in French). France Agricole. p. 540. ISBN 978-2-85557-048-8.

- "L'Encéphalopathie spongiforme bovine : ESB" (PDF). univ-brest.fr (in French). Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- "Encéphalopathie spongiforme bovine (ESB)". Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (in French). 2002. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- Pradier, Françoise. "8 questions que vous pourriez poser à votre boucher". doctissimo (in French). Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- DERIOT, Gérard; BIZET, Jean (2001). "Rapport de la commission d'enquête sur les conditions d'utilisation des farines animales dans l'alimentation des animaux d'élevage et les conséquences qui en résultent pour la santé des consommateurs". Sénat (in French). Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- Sousa, Alain. "Le problème des farines animales". doctissimo (in French). Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- Lledo, Pierre-Marie (2001). Histoire de la vache folle (in French). Presses Universitaires de France. p. 37.

- "Les risques sanitaires liés aux différents usages des farines et graisses d'origine animale et aux conditions de leur traitement et de leur élimination" (PDF). AFSSA (in French). 2001. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- "Nombre de cas d'encéphalopathie spongiforme bovine (ESB) signalés au Royaume-Uni". OIE (in French). 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- "Nombre de cas d'encéphalopathie spongiforme bovine (ESB) signalés chez les bovins d'élevage dans le monde*, hors Royaume-Uni". OIE (in French). 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- Muller, Séverin (2008). À l'abattoir : travail et relations professionnelles face au risque sanitaire (in French). Quae. p. 301. ISBN 978-2-7592-0051-1.

- "VARIANT CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE CURRENT DATA (FEBRUARY 2009)". Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- Postgate, John (2000). Microbes and Man. Cambridge University Press. pp. 140–141.

- "La crise de la vache folle de 1985 à 2004". La documentation française (in French). Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- Landais, E. (1996). Élevage bovin et développement durable (in French). Courrier de l'environnement de l'INRA. pp. 59–72.

- Galinier, Pascal. "L'affaire de la treizième vache". vachefolle.esb.free.fr (in French). Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- Mer, Rémi (2004). "Vache folle : les médias sous pression". Dossier de l'Environnement de l'INRA (in French). 28: 111–117.

- "Que nous prépare la vache folle ?". humanite.fr (in French). 2000.

- Payet, Marc (2000). "La famille d'un jeune malade témoigne pour la première fois". leparisien.fr (in French).

- Lanoy, Patrice; Décugis, Jean-Michel (2000). "Vache Folle : des vérités dérangeantes". Le Figaro (in French).

- Mer, Rémi (2004). "Vache Folle : les médias sous pression – D'une crise à l'autre" (PDF). inra.fr (in French).

- Le Pape, Yves (2004). "La Crise sociale de l'ESB". Dossier de l'Environnement de l'INRA (in French). 28: 155–159.

- Schneidermann, Daniel (2003). Le Cauchemar médiatique (in French). Paris: Denoël. p. 280.

- "2. Une couverture médiatique parfois excessive". Sénat (in French). Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- "5. Les retombées économiques de la crise de la vache folle". INRA (in French). Retrieved 24 April 2009.

- Cabut, Sandrine. "Le bœuf ne fera plus l'andouille". doctissimo (in French). Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- Lemaitre, P. (1996). "Les Quinze vont augmenter les stocks de viande bovine". Le Monde (in French).

- Grosrichard, F. (1996). "La crise de la " vache folle " reste menaçante pour les éleveurs". Le Monde (in French).

- Dorison, Philippe. "VACHE FOLLE : d'un embargo à l'autre ?". Biomagazine (in French). Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- "Statistics provided by U.S. government & compiled by US Meat Export Federation".

- De Fontenay, Elisabeth (2008). Sans offenser le genre humain. Réflexions sur la cause animale (in French). Bibliothèque Albin Michel des idées. pp. 206–209. ISBN 978-2-226-17912-8.

- Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Lettres à l'ashram, protection de la vache (in French).

- "Right-wing Hindus revel in 'mad cow' scare". CNN.

- "La viande française est-elle vraiment plus sûre ?". doctissimo (in French). Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- ""3R special": development of the BSE epidemic among cattle in France". Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- Ducrot, C. (2004). "Épidémiologie de la tremblante et de l'encéphalopathie spongiforme bovine en France". Productions Animales, INRA (in French). 17: 67–77. doi:10.20870/productions-animales.2004.17.HS.3630.

- Court, Marielle (2008). "Bruxelles réfléchit à un retour des farines animales". lefigaro.fr (in French).

- "Viande bovine française : quels contrôles ?". doctissimo (in French). Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- "La vache folle : analyse d'une crise et perspectives d'avenir" (PDF). Science & décision (in French). Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- "Epidémiosurveillance de l'ESB en France" (PDF). AFSSA (in French). 2002. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- "La traçabilité". amibev.org (in French). Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- Gabillat, Claire. "Vache folle : le rapport qui accuse les autorités anglo-saxonnes". doctissimo (in French). Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- Scott, M. (1999). "Compelling transgenic evidence for transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy prions to humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (26): 15137–15142. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9615137S. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.26.15137. PMC 24786. PMID 10611351.

- Wroe, SJ. (2006). "Clinical presentation and pre-mortem diagnosis of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease associated with blood transfusion: a case report". The Lancet. 368 (9552): 2061–2067. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69835-8. PMID 17161728. S2CID 24745868.

- BSE inquiry. The BSE inquiry : Economic Impact and International Trade.

- Kerveno, Yann (2004). "Équarrissage : la ceinture et les bretelles" (PDF). Dossier de l'Environnement de l'INRA (in French). 28: 81–85.

- Schneider, André. "ESB : Le temps de l'angoisse". Journal des accidents et des catastrophes (in French). 15.

Bibliography

- Chateauraynaud, Francis; Torny, Didier (1999). Les sombres précurseurs. Une sociologie pragmatique de l'alerte et du risque (in French). Editions de l'EHESS.

- Lledo, Pierre-Marie (2001). Histoire de la vache folle (in French). Presses Universitaires de France.

- Institut de l'Elevage (2000). Maladies des bovins : manuel pratique (in French). France Agricole. ISBN 978-2-85557-048-8.

- Université de Bretagne Occidentale. L'Encéphalopathie Spongiforme Bovine : E.S.B. (in French).