Macrozamia miquelii

Macrozamia miquelii, is a species of cycad in the plant family Zamiaceae. It is endemic to Queensland and New South Wales in Eastern Australia. Located within sclerophyll forests dominated by eucalyptus trees, the cycad grows on nutrient-poor soils. It is recognised within the Zamiaceae family for its, medium height at 1 m, intermediate size of male and female cones and lighter green leaves compared to other cycads within the plant family of Zamiaceae. The seeds have an orange red sarcotesta which attracts fauna consumption, allowing a mutualistic seed dispersal for the cycad. These seeds are also edible for human consumption if prepared correctly to remove the toxins.

| Macrozamia miquelii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnosperms |

| Division: | Cycadophyta |

| Class: | Cycadopsida |

| Order: | Cycadales |

| Family: | Zamiaceae |

| Genus: | Macrozamia |

| Species: | M. miquelii |

| Binomial name | |

| Macrozamia miquelii | |

| |

| Distribution map from AVH[2] | |

Description

Macrozamia miquelii are acaulescent. The caudex, which can grow to a diameter of 45 cm and 50 cm in height, is usually subterranean with little of it being visible above ground.[3] This cycad has between 20 and 80 slightly glossy dark green leaves (fronds) in its crown, each leaf growing to a length of 2.3 m long. The leaves consist of 80 to 160 leaflets, each leaflet is 15 cm to 50 cm long, 8 mm to 20 mm wide and are covered in grey-brown hairs.[4] Leaflets are discolorous with a dark green and slightly glossy upper surface and a paler green lower surface.[3] Distal leaflets are spaced closely to other leaflets while proximal leaflets are more spread out. The rachis of the Macrozamia miquelii remains straight with a pale green colour and the leaflets are inserted at 40 degree angles to the rachis.[4]

Macrozamia miquelii like all cycads are dioecious.[5] The male cycad develops 1 to 5 male (pollen) cones, each cone measuring 12 cm to 28 cm in length and 4 cm to 7 cm in diameter. These cones are fusiform but curve with age and remain green throughout its lifetime. The female (seed) cycad develops 1 to 3 female cones, each cone measuring 25 cm to 40 cm in length and 10 cm to 15 cm in diameter. The female cone remains green and has a cylindrical shape. Seeds are oblong, with a length of 2 cm to 3 cm and diameter of 1.5 cm to 2 cm.[4] The sarcotesta has an orange yellow colour which turns reddish-orange when the seeds are ripe.[3]

Taxonomy

When originally named in 1862, Ferdinand von Mueller called this cycad, Encephalartos miquelii.[6] The species name honours Dutch botanist Friedrich Anton Wilhelm Miquel. As an early pioneer of cycad systematics, Friedrich Anton Wilhelm Miquel studied numerous species of cycads.[4]

Lawrence Alexander Sidney Johnson lectotypified the name in 1959 using the Thozet collection from Rockhampton. Although Ferdinand von Mueller had already indicated a preferred application, a proposal to conserve the name with Lawrence Alexander Sidney Johnson's lectotype was rejected by the International Association for Plant Taxonomy (IAPT) committee.[7] This occurred as it was considered that Ferdinand von Mueller's later attempt at restricting application of the name did not equate to lectotypification.[4]

Distribution and habitat

Macrozamia miquelii is endemic to both southern Queensland and northern NSW, from Port Curtis District to the upper Richmond River.[3] The cycad is located on ridges and slopes within sclerophyll forests where eucalyptus tree species including the Corymbia citriodora and Eucalyptus crebra dominate the canopy. Scattered within these forests, the cycad grows on low-nutrient stony or sandy soils at an altitude range of 10 m to 540 m.[4]

Ecology

The male cones of Macrozamia miquelii mature from January to March, with growths on the cone called sporophyll.[8] Hanging under the sporophyll are several male reproductive organs known as pollen sacs that produce pollen. Throughout the maturity, the male cone becomes elongated with gaps forming between individual sporophylls. The female cones produce fewer sporophyll and are larger than male cones. Each female cone will have two to eight female reproductive organs known as ovules which if fertilised will develop into seeds. Similarly, as the female cone matures from January to March, it splits apart allowing openings between the cones.[9]

The mature cycad requires a mutualistic relationship with fauna for its pollination and seed dispersal.[10] Thrips are lured to the male cones through the use of a strong and pungent scent.[11] The pollen grains from male cones stick to the thrip's body and can attract more than 50,000 thrips. Female cones also emit a scent when mature, attracting the pollen covered thrips and allowing pollination to occur. Once pollinated, female cones close and expand rapidly.[12]

As the sarcotesta is bright, avian and mammalian species are attracted to the seeds.[13] With no toxins in the sarcotesta, smaller fauna including wallabies, possums and crows strip off the sarcotesta, leaving the seed untouched. This would not contribute to the propagation of Macrozamia miquelii as most seeds would be left within a metre of the parent cycad.[14] Larger fauna such as emus and cassowaries have been observed contributing to seed dispersal as the seeds can be ingested and defecated intact without harming the fauna.[15]

Conservation

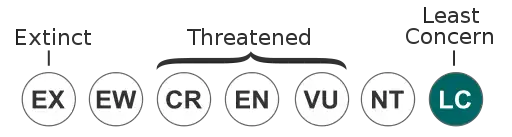

Macrozamia miquelii was rated as least concern by the IUCN in 2009. The IUCN has also indicated the cycad to have a decreasing population trend as a result of a declining quality of habitat.[16] Conservation areas where the cycad species is protected includes Byfield National Park and Mount Archer National Park.[4] The IUCN estimates a total of 10,000 to 20,000 mature individual plants remain within the wild.[16]

Uses

The seeds of the Macrozamia miquelii are edible after being treated.[17] The Aboriginal Australians utilised multiple traditional preparation techniques such as leaching the seeds in water and aging, to remove the toxins within the seeds for consumption.[18] One method of treatment involved pounded seeds being placed within a dilly bag that would then be left in a running stream for 6 days. This would reduce the mass of the seeds to form a paste. The paste would then be baked in ashes making the seeds edible.[19]

The pith of the cycad is also useful as it contains a toxic starch that once processed to remove the toxins, is edible and used in laundries.[5]

Toxicity

Most parts of the Macrozamia miquelii are toxic with the seeds of the cycad having a higher concentration of azoxyglycosides, including cycasin and macrozamin, than other parts of the plant.[20] Other toxins identified within the cycad include β-Methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) which acts as a powerful neurotoxin if ingested. The ingestion of raw cycad seeds by an animal can lead to death and cause nausea and diarrhea in humans as well as death in some cases.[15] Cycad leaves are also dangerous due to β-Methylamino-L-alanine and have been recorded to cause hind end paralysis and death in cattle.[19]

References

- Hill, K.D. (2010). "Macrozamia miquelii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T42012A10622860. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T42012A10622860.en. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- Herbaria, jurisdiction:Australian Government Departmental Consortium;corporateName:Council of Heads of Australasian. "Partners". avh.ala.org.au. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Macrozamia miquelii". plantnet.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- Jones, David L.; Forster, Paul I.; Sharma, Ish K. (2001). "Revision of the Macrozamia miquelii (F.Muell.) A.DC. (Zamiaceae section Macrozamia) group". Austrobaileya. 6 (1): 67–94. doi:10.5962/p.299651. ISSN 0155-4131. JSTOR 41738960. S2CID 260266196.

- Low, Tim (1991). Wild food plants of Australia (Revised ed.). North Ryde NSW, Australia. ISBN 0-207-16930-6. OCLC 25220546.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Encephalartos miquelii F.Muell". www.gbif.org. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- Brummitt, Richard K. (2000). "Report of the Committee for Spermatophyta: 50". Taxon. 49 (4): 799–808. doi:10.2307/1223981. ISSN 1996-8175. JSTOR 1223981.

- "Macrozamia miquelii - Burrawang". www.oznativeplants.com. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- Nadarajan, J.; Benson, E. E.; Xaba, P.; Harding, K.; Lindstrom, A.; Donaldson, J.; Seal, C. E.; Kamoga, D.; Agoo, E. M. G.; Li, N.; King, E. (1 September 2018). "Comparative Biology of Cycad Pollen, Seed and Tissue - A Plant Conservation Perspective". The Botanical Review. 84 (3): 295–314. doi:10.1007/s12229-018-9203-z. ISSN 1874-9372. PMC 6105234. PMID 30174336.

- Mound, Laurence A.; Terry, Irene (2001). "Thrips Pollination of the Central Australian Cycad, Macrozamia macdonnellii (Cycadales)". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 162 (1): 147–154. doi:10.1086/317899. ISSN 1058-5893. JSTOR 10.1086/317899. S2CID 86227343.

- Marullo, Rita; Mound, Laurence (1 January 2002). Thrips and Tospoviruses: Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Thysanoptera. ISBN 978-0-9750206-0-9.

- "Pollination". The Australian Museum. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- "Cycads". www3.nd.edu. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- Hall, John A.; Walter, Gimme H. (2013). "Seed dispersal of the Australian cycad Macrozamia miquelii (Zamiaceae): Are cycads megafauna-dispersed "grove forming" plants?". American Journal of Botany. 100 (6): 1127–1136. doi:10.3732/ajb.1200115. ISSN 0002-9122. JSTOR 23435178. PMID 23711908.

- Hall, J. A.; Walter, G. H. (August 2014). "Relative Seed and Fruit Toxicity of the Australian Cycads Macrozamia miquelii and Cycas ophiolitica: Further Evidence for a Megafaunal Seed Dispersal Syndrome in Cycads, and Its Possible Antiquity". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 40 (8): 860–868. doi:10.1007/s10886-014-0490-5. ISSN 0098-0331. PMID 25172315. S2CID 211490.

- Hill, K. D. (31 October 2009). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Macrozamia miquelii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. doi:10.2305/iucn.uk.2010-3.rlts.t42012a10622860.en. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- Thieret, John W. (1 January 1958). "Economic Botany of the Cycads". Economic Botany. 12 (1): 3–41. doi:10.1007/BF02863122. ISSN 1874-9364. S2CID 1239340.

- Beck, Wendy (1992). "Aboriginal Preparation of Cycas Seeds in Australia". Economic Botany. 46 (2): 133–147. doi:10.1007/BF02930628. ISSN 0013-0001. JSTOR 4255419. S2CID 41448503.

- Whiting, Marjorie Grant (1 October 1963). "Toxicity of cycads". Economic Botany. 17 (4): 270–302. doi:10.1007/BF02860136. ISSN 1874-9364. S2CID 31799259.

- Castillo-Guevara, Citlalli; Rico-Gray, Victor (2003). "The Role of Macrozamin and Cycasin in Cycads (Cycadales) as Antiherbivore Defenses". The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. 130 (3): 206–217. doi:10.2307/3557555. ISSN 1095-5674. JSTOR 3557555.