Lycoperdon perlatum

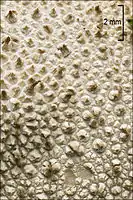

Lycoperdon perlatum, popularly known as the common puffball, warted puffball, gem-studded puffball or devil's snuff-box, is a species of puffball fungus in the family Agaricaceae. A widespread species with a cosmopolitan distribution, it is a medium-sized puffball with a round fruit body tapering to a wide stalk, and dimensions of 1.5 to 6 cm (5⁄8 to 2+3⁄8 in) wide by 3 to 10 cm (1+1⁄8 to 3+7⁄8 in) tall. It is off-white with a top covered in short spiny bumps or "jewels", which are easily rubbed off to leave a netlike pattern on the surface. When mature it becomes brown, and a hole in the top opens to release spores in a burst when the body is compressed by touch or falling raindrops.

| Lycoperdon perlatum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Agaricaceae |

| Genus: | Lycoperdon |

| Species: | L. perlatum |

| Binomial name | |

| Lycoperdon perlatum Pers. (1796) | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| Glebal hymenium | |

| Cap is convex | |

| Hymenium attachment is irregular or not applicable | |

| Stipe is bare | |

| Spore print is brown | |

| Ecology is saprotrophic | |

| Edibility is choice or inedible | |

The puffball grows in fields, gardens, and along roadsides, as well as in grassy clearings in woods. It is edible when young and the internal flesh is completely white, although care must be taken to avoid confusion with immature fruit bodies of poisonous Amanita species. L. perlatum can usually be distinguished from other similar puffballs by differences in surface texture. Several chemical compounds have been isolated and identified from the fruit bodies of L. perlatum, including sterol derivatives, volatile compounds that give the puffball its flavor and odor, and the unusual amino acid lycoperdic acid. Extracts of the puffball have antimicrobial and antifungal activities.

Taxonomy

The species was first described in the scientific literature in 1796 by mycologist Christiaan Hendrik Persoon.[3] Synonyms include Lycoperdon gemmatum (as described by August Batsch in 1783[4]); the variety Lycoperdon gemmatum var. perlatum (published by Elias Magnus Fries in 1829[5]); Lycoperdon bonordenii (George Edward Massee, 1887[6]); and Lycoperdon perlatum var. bonordenii (A.C. Perdeck, 1950[7]).[1][2]

L. perlatum is the type species of the genus Lycoperdon. Molecular analyses suggest a close phylogenetic relationship with L. marginatum.[8]

The specific epithet perlatum is Latin for "widespread".[9] It is commonly known as the common puffball, the gem-studded puffball[10] (or gemmed puffball[11]), the warted puffball,[9] or the devil's snuff-box;[12] Samuel Frederick Gray called it the pearly puff-ball in his 1821 work A Natural Arrangement of British Plants.[13] Because some indigenous peoples believed that the spores caused blindness, the puffball has some local names such as "blindman's bellows" and "no-eyes".[14]

Description

The fruit body ranges in shape from pear-like with a flattened top, to nearly spherical, and reaches dimensions of 1.5 to 6 cm (5⁄8 to 2+3⁄8 in) wide by 3 to 7 cm (1+1⁄8 to 2+3⁄4 in) tall. It has a stem-like base, and is whitish before browning in age.[15] The outer surface of the fruit body (the exoperidium) is covered in short cone-shaped spines that are interspersed with granular warts. The spines, which are whitish, gray, or brown, can be easily rubbed off, and leave reticulate pock marks or scars after they are removed.[11] The base of the puffball is thick. It is initially white, but turns yellow, olive, or brownish in age.[11] The reticulate pattern resulting from the rubbed-off spines is less evident on the base.[16]

In maturity, the exoperidium at the top of the puffball sloughs away, revealing a pre-formed hole (ostiole) in the endoperidium, through which the spores can escape.[17] In young puffballs, the internal contents, the gleba, is white and firm, but turns brown and powdery as the spores mature.[11] The gleba contains minute chambers that are lined with hymenium (the fertile, spore-bearing tissue); the chambers collapse when the spores mature.[17] Mature puffballs release their powdery spores through the ostiole when they are compressed by touch or falling raindrops. A study of the spore release mechanism in L. pyriforme using high-speed schlieren photography determined that raindrops of 1 mm diameter or greater, including rain drips from nearby trees, were sufficient to cause spore discharge. The puffed spores are ejected from the ostiole at a velocity of about 100 cm/second to form a centimeter-tall cloud one-hundredth of a second after impact. A single puff like this can release over a million spores.[18]

.jpg.webp)

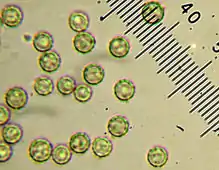

The spores are spherical, thick-walled, covered with minute spines, and measure 3.5–4.5 μm in diameter. The capillitia (threadlike filaments in the gleba in which spores are embedded) are yellow-brown to brownish in color, lack septae,[19] and measure 3–7.5 μm in diameter.[16] The basidia (spore-bearing cells) are club-shaped, four-spored, and measure 7–9 by 4–5 μm. The basidia bear four slender sterigmata of unequal length ranging from 5–10 μm long. The surface spines are made of chains of pseudoparenchymatous hyphae (resembling the parenchyma of higher plants), in which the individual hyphal cells are spherical to elliptical in shape, thick-walled (up to 1 μm), and measure 13–40 by 9–35 μm. These hyphae do not have clamp connections.[20]

Edibility

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,845.5 kJ (441.1 kcal) |

42 g | |

10.6 g | |

44.9 g | |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Copper | 25% 0.5 mg |

| Iron | 42% 5.5 mg |

| Manganese | 29% 0.6 mg |

| Zinc | 5% 0.5 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Lycoperdon perlatum is considered to be a good edible mushroom when young, when the gleba is still homogeneous and white.[22] They have been referred to as "poor man's sweetbread" due to their texture and flavor. The fruit bodies can be eaten after slicing and frying in batter or egg and breadcrumbs,[12] or used in soups as a substitute for dumplings.[23] As early as 1861, Elias Fries recommended them dried and served with salt, pepper, and oil.[24] The puffballs become inedible as they mature: the gleba becomes yellow-tinged then finally develops into a mass of powdery olive-green spores. L. perlatum is one of several edible species sold in markets in the Mexican states of Puebla and Tlaxcala.[25][26] The fruit bodies are appealing to animals as well: the northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus) includes the puffball in their diet of non-truffle fungi,[27] while the "puffball beetle" Caenocara subglobosum uses the fruit body for shelter and breeding.[28] Nutritional analysis indicates that the puffballs are a good source of protein, carbohydrates, fats, and several micronutrients.[21] The predominant fatty acids in the puffball are linoleic acid (37% of the total fatty acids), oleic acid (24%), palmitic acid (14.5%), and stearic acid (6.4%).[29]

The immature 'buttons' or 'eggs' of deadly Amanita species can be confused with puffballs. This can be avoided by slicing fruit bodies vertically and inspecting them for the internal developing structures of a mushroom, which would indicate the poisonous Amanita. Additionally, amanitas will generally not have "jewels" or a bumpy external surface.[30]

The spores' surfaces have many microscopic spines and can cause severe irritation of the lung (lycoperdonosis) when inhaled.[31][32] This condition has been reported to afflict dogs that play or run where the puffballs are present.[33][34]

Similar species

_Kreisel%252C_1989_(Pestle_Puffball)_(2)_crop.jpg.webp)

There are several other puffball species with which L. perlatum might be confused. L. nettyanum, found in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, is covered in granular patches, but these granules adhere more strongly to the surface than those of L. perlatum.[35] L. pyriforme lacks prominent spines on the surface, and grows on rotting wood—although if growing on buried wood, it may appear to be terrestrial. The widely distributed and common L. umbrinum has spines that do not leave scars when rubbed off,[36] a gleba that varies in color from dark brown to purple-brown at maturity, and a purple-tinged base. The small and rare species L. muscorum grows in deep moss. L. peckii can be distinguished from L. pyriforme by the lavender-tinged spines it has when young. L. rimulatum has purplish spores, and an almost completely smooth exoperidium.[11] L. excipuliforme is larger and grayer, and, in mature individuals, the upper portion of its fruit body breaks down completely to release its spores.[14] In the field, L. marginatum is distinguished from L. perlatum by the way in which the spines are shed from the exoperidium in irregular sheets.[36]

Ecology and distribution

A saprobic species, Lycoperdon perlatum grows solitarily, scattered, or in groups or clusters on the ground. It can also grow in fairy rings.[12] Typical habitats include woods, grassy areas, and along roads.[11] It has been reported from Pinus patula plantations in Tamil Nadu, India.[20] The puffball sometimes confuses golfers because of its resemblance to a golf ball when viewed from a distance.[12]

A widespread species with an almost cosmopolitan distribution,[16] it has been reported from Africa (Kenya, Rwanda,[37] Tanzania[38]), Asia (China,[39] Himalayas,[40] Japan,[41] southern India[20] Iran[42]), Australia,[12] Europe,[43] New Zealand,[44] and South America (Brazil).[45] It has been collected from subarctic areas of Greenland, and subalpine regions in Iceland.[46] In North America, where it is considered the most common puffball species, it ranges from Alaska[47] to Mexico,[48] although it is less common in Central America.[49] The species is popular on postage stamps, and has been depicted on stamps from Guinea, Paraguay, Romania, Sierra Leone, and Sweden.[50]

The puffball bioaccumulates heavy metals present in the soil,[51][52] and can be used as a bioindicator of soil pollution by heavy metals and selenium.[53] In one 1977 study, samples collected from grassy areas near the side of an interstate highway in Connecticut were shown to have high concentrations of cadmium and lead.[54] L. perlatum biomass has been shown experimentally to remove mercury ions from aqueous solutions, and is being investigated for potential use as a low-cost, renewable, biosorptive material in the treatment of water and wastewater containing mercury.[55]

Chemistry

Several steroid derivatives have been isolated and identified from fruit bodies of L. perlatum, including (S)-23-hydroxylanostrol, ergosterol α-endoperoxide, ergosterol 9,11-dehydroendoperoxide and (23E)-lanosta-8,23-dien-3β,25-diol. The compounds 3-octanone, 1-octen-3-ol, and (Z)-3-octen-1-ol are the predominant components of the volatile chemicals that give the puffball its odor and flavor.[56] Extracts of the puffball contain relatively high levels of antimicrobial activity against laboratory cultures of the human pathogenic bacteria Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with activity comparable to that of the antibiotic ampicillin.[57] These results corroborate an earlier study that additionally reported antibacterial activity against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Mycobacterium smegmatis.[58] Extracts of the puffball have also been reported to have antifungal activity against Candida albicans, C. tropicalis, Aspergillus fumigatus, Alternaria solani, Botrytis cinerea, and Verticillium dahliae.[59] A 2009 study found L. perlatum puffballs to contain cinnamic acid at a concentration of about 14 milligrams per kilogram of mushroom.[60] The fruit bodies contain the pigment melanin.[61]

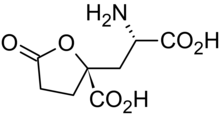

The amino acid lycoperdic acid (chemical name 3-(5(S)-carboxy-2-oxotetrahydrofuran-5(S)-yl)-2(S)-alanine) was isolated from the puffball, and reported in a 1978 publication.[62] Based on the structural similarity of the new amino acid with (S)-glutamic acid, (S)-(+)-lycoperdic acid is expected to have antagonistic or agonistic activity for the glutamate receptor in the mammalian central nervous system. Methods to synthesize the compounds were reported in 1992,[63] 1995,[64] and 2002.[65]

References

- "Synonymy: Lycoperdon perlatum Pers". Index Fungorum. CAB International. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- "Lycoperdon perlatum Pers. 1796". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Persoon CH (1796). Observationes Mycologicae (PDF) (in Latin). Vol. 1. Leipzig, Germany: Petrum Phillippum Wolf. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Batsch AJGK (1783). Elenchus fungorum (PDF) (in Latin). Halle an der Saale, Germany: apud J. J. Gebauer. p. 147.

- Fries EM (1829). Systema Mycologicum (in Latin). Vol. 3. Greifswald, Germany: Ernesti Mauritii. p. 37.

- Massee GE (1887). "A monograph of the genus Lycoperdon (Tournef.) Fr". Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society. 2. 5: 701–27 (see p. 713). Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Perdeck AC (1950). "A revision of the Lycoperdaceae of the Netherlands". Blumea. 6: 480–516 (see p. 505).

- Larsson E, Jeppson M (2008). "Phylogenetic relationships among species and genera of Lycoperdaceae based on ITS and LSU sequence data from north European taxa". Mycological Research. 112 (1): 4–22. doi:10.1016/j.mycres.2007.10.018. PMID 18207380.

- Schalkwijk-Barendsen HME. (1991). Mushrooms of Western Canada. Edmonton, Canada: Lone Pine Publishing. p. 346. ISBN 0-919433-47-2.

- Ammirati JF, McKenny M, Stuntz DE (1987). The New Savory Wild Mushroom. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. p. 194. ISBN 0-295-96480-4.

- Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: A Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. pp. 693–4. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- Dickinson C, Lucas J (1982). VNR Color Dictionary of Mushrooms. New York, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-442-21998-7.

- Gray SF (1821). A Natural Arrangement of British Plants. London, UK: Baldwin, Cradock and Joy. p. 584.

- Roberts P, Evans S (2011). The Book of Fungi. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 520. ISBN 978-0-226-72117-0.

- Trudell, Steve; Ammirati, Joe (2009). Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest. Timber Press Field Guides. Portland, OR: Timber Press. pp. 269–270. ISBN 978-0-88192-935-5.

- Læssøe T, Pegler DN, Spooner B (1995). British Puffballs, Earthstars and Stinkhorns: An Account of the British Gasteroid Fungi. Kew, UK: Royal Botanic Gardens. p. 152. ISBN 0-947643-81-8.

- Miller HR, Miller OK (1988). Gasteromycetes: Morphological and Developmental Features, with Keys to the Orders, Families, and Genera. Eureka, California: Mad River Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-916422-74-7.

- Gregory PH (1949). "The operation of the puff-ball mechanism of Lycoperdon perlatum by raindrops shown by ultra-high-speed Schlieren cinematography". Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 32 (1): 11–5. doi:10.1016/S0007-1536(49)80030-1.

- Miller HR, Miller OK (2006). North American Mushrooms: A Field Guide to Edible and Inedible Fungi. Guilford, Connecticut: Falcon Guide. p. 453. ISBN 0-7627-3109-5.

- Natarajan K, Purushothama KB (1987). "On the occurrence of Lycoperdon perlatum in Pinus patula plantations in Tamil Nadu" (PDF). Current Science. 56 (21): 1117–8.

- Nutritional values are based on chemical analysis of Turkish specimens, conducted by Colak and colleagues at the Department of Chemistry, Karadeniz Technical University. Source: Colak A, Faiz Ö, Sesli E (2009). "Nutritional composition of some wild edible mushrooms" (PDF). Türk Biyokimya Dergisi [Turkish Journal of Biochemistry]. 34 (1): 25–31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- Meuninck, Jim (2017). Foraging Mushrooms Oregon: Finding, Identifying, and Preparing Edible Wild Mushrooms. Falcon Guides. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4930-2669-2.

- Kuo M. (2007). 100 Edible Mushrooms. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-472-03126-9.

- Læssøe T, Spooner B (1994). "The uses of 'Gasteromycetes'". Mycologist. 8 (4): 154–9. doi:10.1016/S0269-915X(09)80179-1.

- Lemin M, Vasquez A, Chacon S (2010). "Etnomicología y comercialización de hongos en mercados de tres poblados del noreste del estado de Puebla, México" [Ethnomycology and marketing of mushrooms in markets in three villages of the northeastern state of Puebla, Mexico]. Brenesia (in Spanish) (73/74): 58–63. ISSN 0304-3711.

- Montoya A, Hernández-Totomoch O, Estrada-Torres A, Kong A, Caballero J (2003). "Traditional knowledge about mushrooms in a Nahua community in the State of Tlaxcala, México". Mycologia. 95 (1): 793–806. doi:10.2307/3762007. JSTOR 3762007. PMID 21148986.

- Thysell DR, Villa LJ, Carey AB (1997). "Observations of northern flying squirrel feeding behavior: use of non-truffle food items". Northwestern Naturalist. 78 (3): 87–92. doi:10.2307/3536862. JSTOR 3536862.

- Suda I. (2009). "Metsamardikate (Coleoptera) uued liigid Eestis" [New woodland beetle species (Coleoptera) in Estonian fauna]. Forestry Studies/Metsanduslikud Uurimused (in Estonian and English). 50 (2009): 98–114. doi:10.2478/v10132-011-0071-0. ISSN 1406-9954.

- Nedelcheva D, Antonova D, Tsvetkova S, Marekov I, Momchilova S, Nikolova-Damyanova B, Gyosheva M (2007). "TLC and GC‐MS probes into the fatty acid composition of some Lycoperdaceae mushrooms". Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies. 30 (18): 2717–27. doi:10.1080/10826070701560629. S2CID 96089499.

- Marley G. (2010). Chanterelle Dreams, Amanita Nightmares: The Love, Lore, and Mystique of Mushrooms. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-60358-214-8.

- Taft TA, Cardillo RC, Letzer D, Kaufman CT, Kazmierczak JJ, Davis JP (29 July 1994). "Respiratory illness associated with inhalation of mushroom spores – Wisconsin, 1994". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 43 (29): 525–6. PMID 8028572. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- Strand RD, Neuhauser EBD, Somberger CF (1967). "Lycoperdonosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 277 (2): 89–91. doi:10.1056/NEJM196707132770209. PMID 6027138.

- Rubensohn M. (2009). "Inhalation pneumonitis in a dog from spores of puffball mushrooms". Canadian Veterinary Journal. 50 (1): 93. PMC 2603663. PMID 19337622.

- Buckeridge D, Torrance A, Daly M (2011). "Puffball mushroom toxicosis (lycoperdonosis) in a two-year-old dachshund". Veterinary Record. 168 (11): 304. doi:10.1136/vr.c6353. PMID 21498199. S2CID 684164.

- Ramsey RW (1980). "Lycoperdon nettyana, a new puffball from western Washington State". Mycotaxon. 11 (1): 185–8.

- Davis RM, Sommer R, Menge JA (2012). Field Guide to Mushrooms of Western North America. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 372. ISBN 978-0-520-95360-4.

- Demoulin V, Dring DM (1975). "Gasteromycetes of Kivu (Zaire), Rwanda and Burundi". Bulletin du Jardin botanique national de Belgique. 45 (3/4): 339–72. doi:10.2307/3667488. JSTOR 3667488.

- Maghembe JA, Redhead JF (1984). "A survey of ectomycorrhizal fungi in pine plantations in Tanzania". East African Agricultural and Forestry Journal. 45 (3): 203–6. doi:10.1080/00128325.1980.11663047. ISSN 0012-8325.

- Zhishu B, Zheng G, Taihui L (1993). The Macrofungus Flora of China's Guangdong Province. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. p. 555. ISBN 978-962-201-556-2.

- Thind KS, Thind IPS (1982). "Gasteromycetes of the Himalayas, India. 10". Research Bulletin of the Panjab University Science. 33 (1–2): 139–50. ISSN 0555-7631.

- Kasuya T. (2004). "Gasteromycetes of Chiba Prefecture, Central Honshu, Japan – I. The family Lycoperdaceae". Journal of the Natural History Museum and Institute Chiba. 8 (1): 1–11. ISSN 0915-9452.

- Asef M.R. (2020). Field guide of Mushrooms of Iran. Tehran: Iran-Shanasi Press. p. 360. ISBN 9786008351429.

- Jordan M. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Fungi of Britain and Europe. London, UK: Frances Lincoln. p. 357. ISBN 0-7112-2378-5.

- Chu-Chou M, Grace LJ (1983). "Hypogeous fungi associated with some forest trees in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 21 (2): 183–90. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1983.10428543.

- Baseia UG (2005). "Some notes on the genera Bovista and Lycoperdon (Lycoperdaceae) in Brazil". Mycotaxon. 91: 81–6.

- Jeppson M. (2006). "The genus Lycoperdon in Greenland and Svalbard". In Boertmann D, Knudsen H. (ed.). Arctic and Alpine Mycology. Meddelelser om Grønland Bioscience. Vol. 6. Copenhagen, Denmark: Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-87-635-1277-0.

- Orr DB, Orr RT (1979). Mushrooms of Western North America. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-520-03656-5.

- Moreno G, Lizárraga M, Esqueda M, Coronado ML (2010). "Contribution to the study of gasteroid and secotioid fungi of Chihuahua, Mexico". Mycotaxon. 112: 291–315. doi:10.5248/112.291.

- Garner JHB (1956). "Gasteromycetes from Panama and Costa Rica". Mycologia. 48 (5): 757–64. doi:10.2307/3755385. JSTOR 3755385.

- Moss MO (1998). "Gasteroid Basidiomycetes on postage stamps". Mycologist. 12 (3): 104–6. doi:10.1016/S0269-915X(98)80005-0.

- Ylmaz F, Işloǧlu M, Merdivan M (2003). "Heavy metal levels in some macrofungi" (PDF). Turkish Journal of Botany. 27 (1): 45–56. ISSN 1300-008X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Falandysz J, Lipka K, Kawano M, Brzostowski A, Dadej M, Jedrusiak A, Puzyn T (2003). "Mercury content and its bioconcentration factors in wild mushrooms at Łukta and Morag, northeastern Poland". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (9): 2832–6. doi:10.1021/jf026016l. PMID 12696981.

- Quince J-P (1990). "Lycoperdon perlatum, un champignon accumulateur de métaux lourds et de sélènium" [Lycoperdon perlatum a fungus accumulating heavy metals and selenium]. Mycologia Helvetica (in French). 3 (4): 477–86. ISSN 0256-310X.

- McCreight JD, Schroeder DB (1977). "Cadmium, lead and nickel content of Lycoperdon perlatum Pers. in a roadside environment". Environmental Pollution. 13 (3): 265–8. doi:10.1016/0013-9327(77)90045-3.

- Sari A, Tuzen M, Citak D (2012). "Equilibrium, thermodynamic and kinetic studies on biosorption of mercury from aqueous solution by macrofungus (Lycoperdon perlatum) biomass". Separation Science and Technology. 47 (8): 1167–76. doi:10.1080/01496395.2011.644615. S2CID 96041544.

- Szummy A, Adamski M, Winska K, Maczka W (2010). "Identyfikacja związków steroidowych i olejków eterycznych z Lycoperdon perlatum" [Identification of steroid compounds and essential oils from Lycoperdon perlatum]. Przemysł Chemiczny (in Polish). 89 (4): 550–3. ISSN 0033-2496.

- Ramesh C, Pattar MG (2010). "Antimicrobial properties, antioxidant activity and bioactive compounds from six wild edible mushrooms of western ghats of Karnataka, India". Pharmacognosy Research. 2 (2): 107–12. doi:10.4103/0974-8490.62953. PMC 3140106. PMID 21808550.

- Dulger B. (2005). "Antimicrobial activity of ten Lycoperdaceae". Fitoterapia. 76 (3–4): 352–4. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2005.02.004. PMID 15890468.

- Pujol V, Seux V, Villard J (1990). "Research of antifungal substances produced by higher fungi in culture". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 48 (1): 17–22. ISSN 0003-4509.

- Barros L, Dueñas M, Ferreira ICFR, Baptista P, Santos-Buelga C (2009). "Phenolic acids determination by HPLC-DAD-ESI/MS in sixteen different Portuguese wild mushrooms species". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 47 (6): 1076–9. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2009.01.039. PMID 19425182.

- Almendros G, Martín F, González-Vila FJ, Martínez AT (1987). "Melanins and lipids in Lycoperdon perlatum fruit bodies". Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 89 (4): 533–7. doi:10.1016/S0007-1536(87)80087-6. hdl:10261/59001.

- Lamotte JL, Oleksyn B, Dupont L, Dideberg O, Campsteyn H, Vermiere M (1978). "The crystal and molecular structure of 3-[(5S)-5-carboxy-2-oxotetrahydrofur-5-yl]-(2S)-alanine (lycoperdic acid)". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 34 (12): 3635–8. doi:10.1107/S0567740878011772.

- Kaname M, Yoshifuji S (1992). "1st synthesis of lycoperdic acid". Tetrahedron Letters. 33 (52): 8103–4. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)74730-7.

- Yoshifuji S, Kaname M (1995). "Asymmetric synthesis of lycoperdic acid". Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 43 (10): 1617–20. doi:10.1248/cpb.43.1617. ISSN 0009-2363.

- Makino K, Shintani K, Yamatake T, Hara O, Hatano K, Hamada Y (2002). "Stereoselective synthesis of (S)-(+)-lycoperdic acid through an endo selective hydroxylation of the chiral bicyclic lactam enolate with MoOPH". Tetrahedron. 58 (48): 9737–40. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01254-1.