Lusona

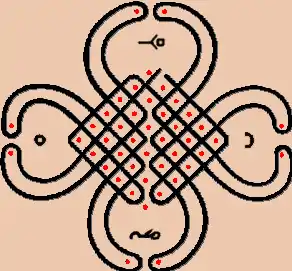

Sona (sing. lusona) drawing is an ideographic tradition known across eastern Angola, northwestern Zambia and adjacent areas of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and is mainly practiced by the Chokwe and Luchazi peoples.[1] These ideographs function as mnemonic devices to help remember proverbs, fables, games, riddles and animals, and to transmit knowledge.[2]

History

Origins

According to ethnologist Gerhard Kubik, this tradition must be ancient and certainly pre-colonial, as observers independently collected the same ideographs among peoples separated for generations. Additionally, early petroglyphs from the Upper Zambezi area in Angola and Citundu-Hulu in the Moçâmedes Desert exhibit structural similarities with lusona ideographs.[3] For example, a lusona known as cingelyengelye, and a lusona showing interlaced loops known as zinkhata, both appear in the rock arts of the Upper Zambezi recorded by José Redinha.[4][3]

Those petroglyphs date from a period between the 6th century BC and the 1st-century BC.[5] It's possible that those petroglyphs and Sona ideographs are related, however there is no direct evidence that this is the case, other than the similarities and the geographic location.

Post-16th century

One of the most basic lusona, katuva vufwati, sometimes appears on objects of trade carried by people in the Kingdoms of Matamba and Ndongo, that we can sometimes see depicted by the Italian missionary Antonio Cavazzi de Montecuccolo in watercolor drawings from his book about those kingdoms.[6]

Scene of iron-working in 1650s Angola, with Lusona depicted on the upper right, below the crown

Scene of iron-working in 1650s Angola, with Lusona depicted on the upper right, below the crown Scene of fiber textile trade in 1650s Angola, with Lusona depicted on the blue scarf on the left.

Scene of fiber textile trade in 1650s Angola, with Lusona depicted on the blue scarf on the left. Scene of ceremonial procession in 1650s Angola, with Lusona depicted on the chest

Scene of ceremonial procession in 1650s Angola, with Lusona depicted on the chest

Later, after the 20th century, various ethnographers and anthropologists would write on Sona ideographs, one of the first being Hermann Baumann in 1935 with his book "Lunda".[6][7]

Usage

Sona ideographs are sometimes used as murals, and most of the time executed in the sand. To make them, drawing experts — after cleaning and smoothing the ground — would impress equidistant dots and draw a continuous line between them. The dots can represent trees, persons or animals, while the lines can represent paths, rivers, fences, walls, contours of a body, etc.[8]

Mathematical properties

80% of the ideographs are symmetric and 60% are mono-linear.[9] They are an example of the use of a coordinate system and geometric algorithms.[2]

Geometric algorithms

Sona drawings can be classified by the algorithms used for their construction. Paulus Gerdes identified six algorithms, most commonly the "plaited-mat" algorithm, which seems to have been inspired by mat weaving.[10]

Chaining rules and theorems

Various studies suggest that the drawing experts knew specific rules of "chaining" and "elimination" relating to the systematic construction of monolinear figures. Studies suggest that the "drawing experts" who invented these rules knew why they were valid, and could prove in one way or another the validity of the theorems that these rules express.[11]

It is difficult to find accounts of theorems developed by the drawing experts to generalize specific patterns relating to dimension and monolinearity/polylinearity,[9] as this tradition was secret and in extinction when it started to be recorded.

However, the drawing experts possibly knew that rectangles with relatively prime dimensions give one-line drawings. This idea is supported by the fact that of the 30 smallest relatively prime rectangular shapes, 75% appears among the documented drawings. It is further possible that they knew that if a square of a dot is added to a one-line lusona, the lusona would still be mono-linear. It seems clear that they had experimentally discovered this fact for 2 X 2 squares.[12]

References

- Gerhard Kubik 2006, p. 1.

- "On mathematical elements in the Tchokwe "Sona" tradition Gerdes, Paulus. 1990. For the Learning of Mathematics10(1), 31–34". Historia Mathematica. 18 (2): 198. 1991. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(91)90542-6. ISSN 0315-0860.

- Gerhard Kubik 2006, p. 229.

- I. Hodder 2013, p. 228.

- José Redinha 1948.

- Gerhard Kubik 2006, p. 4.

- Gerhard Kubik 2006, p. 241.

- I. Hodder 2013, p. 210-213.

- Daniel Ness; Stephen J. Farenga; Salvatore G. Garofalo (12 May 2017). Spatial Intelligence: Why It Matters from Birth through the Lifespan. Taylor & Francis. p. 56–57. ISBN 978-1-317-53118-0.

- Paulus Gerdes 1999, p. 163-167.

- Gerdes, Paulus (1994). "On mathematics in the history of Sub-Saharan Africa". Historia Mathematica. 21 (3): 355. doi:10.1006/hmat.1994.1029. ISSN 0315-0860.

- Chavey, Darrah. "Sona Geometry". Archived from the original on 2018-11-07.

External links

- Gerhard Kubik (2006). Tusona: Luchazi Ideographs : a Graphic Tradition of West-Central Africa. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-7601-2.

- Paulus Gerdes (2006). Sona Geometry from Angola: Mathematics of an African Tradition. Polimetrica. ISBN 978-88-7699-055-7.

- Paulus Gerdes (30 September 1999). Geometry from Africa: Mathematical and Educational Explorations. MAA. ISBN 978-0-88385-715-1.

- I. Hodder (12 November 2013). The Meanings of Things: Material Culture and Symbolic Expression. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-76232-4.

- José Redinha (1948). As Gravuras Rupestres Do Alto Zambeze E Primeira Tentativa Da Sua Interpretação. [With Illustrations, Maps and Plans.].