Ludovico da Bologna

Ludovico da Bologna[lower-alpha 1] (fl. 1431/1454–1479) was an Italian diplomat and churchman. A lay Franciscan, he traveled extensively on diplomatic missions for both the Holy See and various powers, both Christian and Islamic. The overarching goal of his travels was the creation of an alliance against the rising power of the Ottoman Empire. In 1461, he was named Patriarch of Antioch, but he never received canonical investiture.

His first missions, to the Holy Land, Ethiopia and India, were aimed at church unity, but it is not known if he ever got past the Holy Land. He traveled to Georgia and Persia in 1457 and 1458, returning to Europe with a major embassy from the eastern rulers. With this embassy, he traveled throughout Europe in 1460–1461 to drum up support for an anti-Ottoman crusade. His career languished, however, after he had himself consecrated patriarch uncanonically.

In 1465, he moved between the Holy See, the Crimean Khanate and Poland to build an anti-Ottoman alliance. This drew him for a time into Danish service. In the 1470s, he moved between Persia, the Holy See and Burgundy. The untimely deaths of his Persian and Burgundian patrons in 1477–1478 rendered his efforts fruitless. His date of death is unknown.

Family and early life

Ludovico came from a wealthy and politically connected merchant family.[5] He was born at Ferrara, probably around the third decade of the 15th century, possibly as early as 1410.[3][5][6] His father, Antonio di Severo, died before 1438. His grandfather, who moved the family from Bologna, made a fortune in the lumber trade. His cousin Severo was the chancellor and secretary of Duke Ercole I of Ferrara between 1491 and 1500.[5]

Nothing of Ludovico's education is known before he became a lay member of the Observant Franciscans.[5] In the 16th century, Marianus of Florence traced his membership back to 1431, identifying him with the Ludovico da Bologna[lower-alpha 2] who was one of six Franciscans (including Giovanni da Capestrano) in a chapter formed by Pope Eugene IV to consider the means of protecting eastern Christians from heresy and the Ottomans. He has also been identified with the letter-bearer (baiulus litterarum) of the same name sent by Alberto Berdini da Sarteano from Jerusalem to Rome in 1436, and with a Ludovico da Bologna who visited Constantinople and Caffa with two brother friars in 1437 on a mission to deliver the papal invitation to the Council of Ferrara to the Armenians.[6] The identification of the anti-Ottoman diplomat Ludovico with the Ludovico of the 1430s has, however, been doubted on the grounds that they require Ludovico be either unrealistically young at the start of his career or unrealistically old at its end in 1479.[5]

Diplomatic career

Missions to the Holy Land, Ethiopia and India (1454–1457)

The first certain mention of Ludovico is in a bull issued by Pope Nicholas V on 28 March 1454. Living in Jerusalem at the time, he and two companions were granted privileges and dispensation to go to Ethiopia and India. This was part of a papal strategy to bring the eastern churches into papal obedience and create a global anti-Ottoman alliance.[lower-alpha 3] At some point, Ludovico returned to Rome and received money for further missions in Ethiopia, India and the Holy Land, according to two bulls issued on 11 May 1455 and 10 January 1456 by Pope Calixtus III, who permitted him to take along four companions.[5][7] During his time in Italy, he visited his native Ferrara on 19 November 1455. The funds raised in October by Duke Borso of Ferrara for a crusade may have been related to Ludovico's visit.[7]

From Ferrara, Ludovico set out for Ethiopia and India. He was back in Rome by late 1456 or early 1457, bearing "letters from Asian rulers" and accompanied by eight Ethiopian monks.[7] It is certain, however, that he could not have visited Ethiopia and India and returned in this time. It is possible, given the imprecise European geographical knowledge of the time, that he did indeed visit or at least get near a place he considered "Ethiopia".[7] Thus, although papal documents suggest that he should have made at least two trips to Ethiopia and India, it seems quite unlikely that he ever made it.[8] His way was most likely blocked by the Mamluks.[9] The actual results of all these early missions are therefore unknown.[8]

Missions to Georgia and Persia (1457–1459) and return embassy (1460–1461)

In 1457, Ludovico was in Georgia and Persia. It appears he undertook this journey on his own initiative after finding the way to Ethiopia and India difficult or impossible.[8] His explanation for his actions must have been convincing, since he was entrusted with further missions.[9] On 22 November 1457, Calixtus issued a letter of credence for Ludovico in the form of a bull addressed to Uzun Hasan, ruler of the Aq Qoyunlu. It was followed by a similar letter (but not bull) dated 1 December to Qvarqvare II, duke of Samtskhe. On 19 December, Calixtus addressed a bull to the Christians of Persia and Georgia, in which he mentions Ludovico's previous visit to them.[10] In the bull of 19 December and another dated 30 December, Calixtus charges Ludovico as papal nuncio with bringing the Christians of the southern Caucasus under a single authority and fomenting an anti-Ottoman alliance, if possible in conjunction with the Ethiopian emperor Zara Yaqob.[5]

Ludovico returned to the region in 1458 and in October Pope Pius II issued a bull confirming his mission to the "kings of Iberia, Armenia and Mesopotamia".[5][10] In 1460, he returned to Europe with ambassadors from several eastern states. This embassy left a profound impression wherever it traveled.[5]

Ludovico's embassy visited the court of the Emperor Frederick III in October 1460, before traveling to Venice, then Florence (14 December) and Rome (26 December) for an audience with the pope. The envoys represented David Komnenos, emperor of Trebizond;[lower-alpha 4] Qvarqvare of Samtskhe, his vassal; and George VIII, king of Georgia. Letters from the last two were presented to the pope and to Pasquale Malipiero, Doge of Venice.[lower-alpha 5] According to the letters, several other principalities of the East were interested in joining the alliance against the Ottomans, including the Uzun Hasan, the Ramadanids of Adana and several lesser Georgian princes.[lower-alpha 6] At the meeting in Rome, the envoys pressed Pius to appoint Ludovico patriarch of Antioch, which the pope did on 9 January 1461. The appointment was not to take effect, however, until the completion of his mission and the determination of the boundaries of the patriarchate. Ludovico was still a layman at this stage, having never taken holy orders or even entered the subdiaconate.[5]

From Rome, with letters of credence from the pope, Ludovico and the envoys set out for Florence and Milan. Arriving at the latter in March, their message was received favourably by Duke Francesco Sforza, who had his diplomat in Rome, Ottone del Carretto, advocate for Ludovico's patriarchal title. On 21 May 1461, the embassy arrived in Burgundy and was received with celebration by Duke Philip the Good.[lower-alpha 7] With Philip, Ludovico and the envoys attended the funeral of King Louis XI of France and the coronation of Charles VII. While Philip committed himself to an anti-Ottoman crusade, the new king of France did not. The embassy left Burgundy in early October and returned to Rome, where Ludovico encountered Francesco Sforza advocating on behalf of his patriarchate. In fact, Ludovico had had himself secretly consecrated that year in Venice and was forced to flee Rome.[5]

Eastern and Northern Europe (1465–1469)

Nothing is known of Ludovico's activities over the next three years. In 1465, according to Polish sources, he traveled to the Crimean Khanate on papal business and then came to Poland as the ambassador of Khan Haji Giray. He presented himself to Casimir IV of Poland as the patriarch of Antioch and pressed for an alliance with Crimea against the Ottomans.[5]

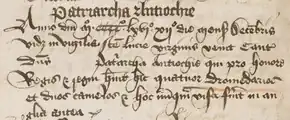

On 12 December 1466, according to John Stone's Chronicle, "there came to Canterbury ... the Lord Patriarch of Antioch, who, in honor of the king and queen, had here four dromedaries and two [Bactrian] camels." Ludovico's mission to England is not otherwise recorded, but the Chronicle is contemporary and John Stone an eyewitness. Of the gifts presented to King Edward IV of England and Elizabeth Woodville, one camel seems to been sent on to Ireland in 1472.[1] In 1467, Ludovico arrived in Denmark to convince King Christian I of Denmark to commit to a crusade against the Turks.[11] He visited Denmark several times in the 1460s. He may have convinced Christian to launch an expedition towards Greenland with the goal of finding a northwest passage to India and Prester John,[12]

In 1468, according to 18th-century Swedish sources, Ludovico served as the Danish envoy to Poland and the autonomous city of Danzig, his mission being to prevent them from allying with King Charles VIII of Sweden against Denmark. In 1469, he was in Denmark helping negotiate a peace with Sweden.[5]

Working the Aq Qoyunlu alliance (1471–1479)

In 1471, Ludovico was back in Italy as the ambassador of Uzun Hasan to Pope Paul II. In a bull dated 19 February 1472, Pope Sixtus IV confirmed his appointment as patriarch of Antioch sub conditione, that is, still subject to certain future conditions. In April, Sixtus renewed Ludovico's mission to construct an anti-Ottoman alliance. In 1473, Ludovico went to Trier, where Frederick III was holding court and where he met Charles the Bold, who had succeeded Philip as duke of Burgundy. Charles named him his ambassador to Uzun Hasan. Ludovico arrived in the Aq Qoyunlu capital of Tabriz on 30 May 1475, where he met the Venetian ambassador Ambrogio Contarini. Uzun Hasan sent back both ambassadors with expressions of his willingness to move against the Ottomans.[5]

During his return journey, Ludovico was imprisoned for a time in Russia. He was back in Rome on 31 December 1477, when Sixtus IV dispatched him again to the courts of Western Europe to drum up support for the anti-Ottoman crusade. In 1478, he visited Frederick III in Germany. By the time he visited the Burgundian court at Brussels in February 1479 the situation had changed drastically. Charles the Bold and Uzun Hasan were both dead. The new duke, Maximilian of Habsburg, was uninterested in pursuing the anti-Ottoman alliance, but paid Ludovico 36 pounds for his information.[5]

There is no further mention of Ludovico after February 1479. The date and place of his death are unknown.[5]

Legacy

Questions have been raised by later historians about the authenticity of some of Ludovico's claims. In the Middle Ages, "when reliable means of personal identification hardly existed", determining that a visitor from afar was who he claimed to be was difficult. Likewise, absent effective means of telecommunication, it was difficult to determine if an envoy had followed instructions and represented himself accurately. This created space for swindlers and charlatans. Several modern scholars have placed Ludovico in this space.[8]

Anthony Bryer is largely responsible for the poor modern reputation of Ludovico.[8] While he refused to "deny [Ludovico']s energy or sincerity", Bryer wrote that "he seems to have been too glib and later obsessed with something of the attitude of a Baron Corvo towards the Church." For Bryer, the "whole story is an example of how defective [Near Eastern] communications with Europe could become."[13] Kenneth Setton was more direct in labeling the embassy of 1460 "false" and Ludovico "an impostor and a charlatan".[14] Georgian scholars, on the other hand, have tended to accept Ludovico's embassy without question.[13]

Giorgio Rota, while admitting that Ludovico's "modus operandi may occasionally have made him suspect", notes that he had the confidence of many rulers and was clearly seen as a valuable asset.[8] For Paolo Evangelisti, his service across decades to several popes and dukes of Burgundy strongly suggests that he was what he appeared to be: an effective diplomat.[5] Benjamin Weber also accepts the authenticity of Ludovico's embassy.[15]

Ludovico appears in The House of Niccolò series of historical novels by Dorothy Dunnett.[3]

Notes

- His full name is sometimes given as Ludovico Severi da Bologna,[1] Lodovico Severi da Bologna[2] or Ludovico de Severi da Bologna.[3] His first name may also be given as Luigi.[4]

- In the Latin of the document, Ludovicus bononiensis.[6]

- Marianus was confused in part by the similarity of Ludovico's missions to those of Alberto Berdini da Sarteano in the 1430s.[5]

- The Trapezuntine ambassador was Michele Alighieri, a descendant of Dante.[5]

- The Republic of Venice sent a favourable reply to Trebizond dated 15 December 1460.[5]

- These last included Liparit of Mingrelia, Bagrat of Imereti, Rabia of Abkhazia and Mamia Gurieli, a Trapezuntine vassal.[5]

- Ludovico established a strong relationship with the House of Valois-Burgundy, working to enhance its prestige and help it obtain a royal title.[5]

References

- Green 2018.

- Walsh 1977, p. 70.

- Morrison 2002, pp. 217–220.

- Salvadore 2017, p. 79 n. 34.

- Evangelisti 2006.

- Rota 2018, pp. 54–55.

- Rota 2018, pp. 55–56.

- Rota 2015, pp. 165–168.

- Salvadore 2017, p. 65.

- Rota 2018, p. 56.

- Jensen 2007, p. 98.

- Jensen 2007, p. 194.

- Bryer 1965, pp. 178–179.

- Rota 2018, p. 51.

- Weber 2012, pp. 111–114.

Bibliography

- Bryer, Anthony A. M. (1965). "Ludovico da Bologna and the Georgian and Anatolian Embassy of 1460–1461" (PDF). Bedi Kartlisa. XIX–XX: 178–198. Reprinted with the same pagination in The Empire of Trebizond and the Pontos (London: Variorum Reprints, 1980).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Devisse, Jean; Mollat, Michel (2010) [1979]. David Bindman; Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (eds.). The Image of the Black in Western Art, Volume II: From the Early Christian Era to the "Age of Discovery", Part 2: Africans in the Christian Ordinance of the World (New ed.). Harvard University Press.

- Evangelisti, Paolo (2006). "Ludovico da Bologna". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 66: Lorenzetto–Macchetti (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Green, Caitlin R. (2018). "Were There Camels in Medieval Britain? A Brief Note on Bactrian Camels and Dromedaries in Fifteenth-century Kent". The Personal Website and Blog of Dr Caitlin R. Green. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- Jensen, Janus Møller (2007). Denmark and the Crusades, 1400–1650. Brill.

- Morrison, Elspeth (2002). The Dorothy Dunnett Companion, Volume II. Vintage Books.

- Richard, Jean (1980). "Louis de Bologne, patriarche d'Antioche, et la politique bourguignonne envers les États de la Méditerranée orientale". Publications du Centre Européen d'Études Bourguignonnes. 20: 63–69. doi:10.1484/j.pceeb.3.131.

- Rota, Giorgio (2015). "Real, Fake or Megalomaniacs? Three Suspicious Ambassadors, 1450–1600". In Miriam Eliav-Feldon; Tamar Herzig (eds.). Dissimulation and Deceit in Early Modern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 165–183. doi:10.1057/9781137447494_11.

- Rota, Giorgio (2018). "Taking Stock of Ludovico da Bologna". Studia et Documenta Turcologica. 5–6 (Special Issue: Research on the Turkic World): 47–75.

- Salvadore, Matteo (2017). The African Prester John and the Birth of Ethiopian–European Relations, 1402–1555. Routledge.

- Walsh, Richard J. (1977). "Charles the Bold and the Crusade: Politics and Propaganda". Journal of Medieval History. 3 (1): 53–86. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(77)90040-9.

- Weber, Benjamin (2012). "Vrais et faux Éthiopiens au XVe siècle en Occident? Du bon usage des connexions". Annales d'Éthiopie (27): 107–126.

- Weber, Benjamin (2017). "Toward a Global Crusade? The Papacy and the Non-Latin World in the Fifteenth Century". In Norman Housley (ed.). Reconfiguring the Fifteenth-Century Crusade. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 11–44.