Lucas Watermills Archaeological Sites

The Lucas Watermills Archaeological Sites are two heritage-listed archaeological sites in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The sites comprise the remnants of two convict-era watermills, the Brisbane Mill on the Williams Creek at Creekwood Reserve, Voyager Point and the Woronora Mill on the Woronora River at Barden Ridge. The original watermills were designed by John Lucas and built from 1822 to 1825 by assigned convict labour. The sites were added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 30 August 2017.[1][2]

| Lucas Watermills Archaeological Sites | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Brisbane Mill archaeological site | |

| Location | Creekwood Reserve, Voyager Point, City of Liverpool, Sydney New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 34.0457°S 151.0075°E |

| Built | 1822–1825 |

| Architect | John Lucas |

| Official name | Lucas Watermills Archaeological Sites; The Brisbane Mill; The Woronora Mill |

| Type | state heritage (archaeological-maritime) |

| Designated | 30 August 2017 |

| Reference no. | 1989 |

| Type | Other - Maritime Industry |

| Category | Maritime Industry |

| Builders | Convict labour |

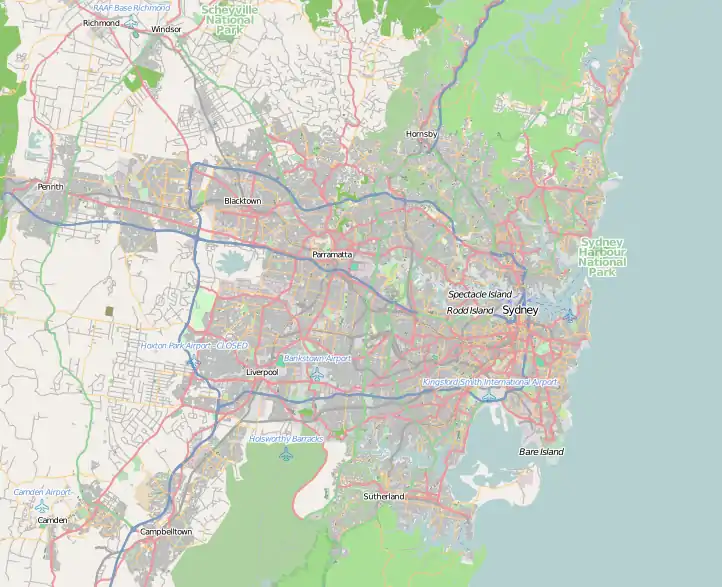

Location of Lucas Watermills Archaeological Sites in Sydney | |

History

Early milling in New South Wales

In the first years of the colony of New South Wales, food production was problematic. The colonists relied on traditional European farming methods and crops which were not always suited to the Australian climate and conditions. While the production of wheat was restricted by climate, soil fertility and plant diseases, the conversion of grain to flour was largely influenced by issues of technology transfer. The adaptation of technology to a new physical and social environment was compounded by the restricted availability of skilled labour.[1]

Experienced millers and millwrights were in short supply in the early colony.[3] The First Fleet had arrived with four millstones but with no millwrights nor suitable millstream a substantial milling enterprise was not possible. The first grain was ground with forty iron hand mills which quickly wore and had an output as little as one bushel per twenty four hours.[4] As early as 1791 Governor Phillip noted that a windmill was urgently needed, although Lieutenant-Governor Philip Gidley King argued that the building of a mill would be too labour-intensive and expensive and stone querns presented a more practical option.[5] Governor Phillip sent several requests for skilled tradesmen, to no avail. In 1793 a convict called Wilkinson eventually produced a treadmill. The treadmill garnered only one bushel per hour with two men walking the boards.[6] Better treadmills followed with some still in use till 1825 for punishment. Horses and bullocks were also used to power mills such as that at Cox's estate at Winbourne and a mobile mill in the Hunter Valley, both operating in the 1830s.[7][1]

When Governor Hunter arrived in 1795 he brought designs and components for a windmill and by 1797 one had been erected at Millers Point in Sydney. Despite this one success the industry remained at a standstill. Mill technology was not easily acquired and implemented without the knowledge of experienced skilled tradesmen. Carpenters were also working with new timbers whose properties they were unfamiliar with. Various other problems including storms, theft, inexperienced operators and an economy drive by the British government further slowed the development of milling. A second windmill, at Parramatta, was eventually built in 1805,[3] but by 1799 when Governor Hunter departed, the Sydney mill was the only operating unit and most milling was still being done by hand.[8][1]

Meanwhile, both the first watermill and the first windmill in the colony had been built in 1794 on Norfolk Island under the direction of Lieutenant-Governor King. King was advantaged by the availability of more suitable timber and the use of Nathaniel Lucas, a convict who was an experienced carpenter with knowledge of millwrighting.[9] When King became Governor of New South Wales, he found that transfer of British mill technology to Sydney continued to be limited by the continuing lack of skilled tradesmen, and building materials and techniques, particularly suitable timber and strong mortar. The output of the one operational mill, at only six bushels per hour, could not meet the demand of the increased population and increased wheat production.[10] King implemented regulation to control the quality and price of bread and moved to increase milling capacity. Under his direction Nathaniel Lucas prefabricated two post mills and quarried millstones on Norfolk Island. One was erected in 1797 at Miller's Point[11] and was operated by the government. The other, erected in The Domain, was operated privately by Lucas and later Kable.[12] Government-owned mills began to be supplemented by private enterprises in this way.[4] Nathaniel Lucas built several more mills which he operated privately and was followed into the milling and building trade by his son John.[1]

The development of water mills, specifically, was hampered by the Australian climate, characterised by variable rainfall and consequent variation in river flow. Early attempts at Parramatta in 1779 and 1803 failed due to intermittent water flows and dam collapse, poor sighting, bad construction and a continuing lack of skilled labour. Even after significant repairs the output was disappointing,[13] and much grain was shipped down to Sydney for milling.[14] However, in the next 10 years, understanding of the local conditions improved, designs were adapted and skilled labour increased.[1]

The number of mills in the county of Cumberland began to decrease in the 1860s due to decreased grain production in the area and the opening up of new agricultural land. There was a massive spread of mills into expanding rural areas in the second half of the nineteenth century till the development of the rail system and cheaper transport costs along with more capital intensive technology encouraged the concentration of milling in capital cities in the early twentieth century.[4] Steam power was developed in England at the end of the eighteenth century and was first implemented in Australian at Dickson's steam mill near Darling Harbour in 1815. Steam mills became common by the 1830s and became the dominant type of mill from the 1850s.[15] From the late 1870s there was a gradual change to roller mills and increasing centralisation.[16][1]

There were 11 mills in 1821, 46 by 1830, 100 by1840 and a peak of around 200 before the start of centralisation in the 1880s.[17][1]

Nathaniel Lucas

Nathaniel Lucas, a builder, joiner and carpenter, was transported to Sydney as a convict in the First Fleet. Upon his arrival he was among fifteen convicts specially selected for their character and vocation to pioneer Norfolk Island, arriving on 6 March 1788.[18][1]

He married one of the fifteen convicts, Olivia Gascoine, and the two had thirteen children between 1789 and 1807.[1]

Having proven his unmatched skill, Nathaniel was named master carpenter in 1795. In addition to supervising the construction of many of the island's buildings, he constructed an overshot mill on Norfolk Island in 1795. This was notable as the first successful mill of this type in the colony.[1]

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reported his return to Sydney on 17 March 1805 to take up the position of Superintendent of Carpenters in Sydney. With him on HMS Investigator came two prefabricated, disassembled windmills and several mill stones fabricated on Norfolk Island.[19] The two smock mills were erected; one above the Rocks and the other in what is now the Domain. The Sydney Gazette and NSW Advertiser on 16 February 1806 described Nathaniel Lucas erecting an octagonal smock mill near the Esplanade of Port Phillip, the present site of the Sydney Observatory. This mill had a height of 40 feet with a base diameter of 22 feet and worked 2 pairs of Norfolk Island mill stones. Nathaniel is credited with building six mills. He apprenticed at least one of his sons, John, in the building and millwright trades at his mills at Sydney and Liverpool from around 1805–1815.[19][1]

Nathaniel's success extended to various entrepreneurial pursuits. By 1809 he was building and selling boats. For his own uses he built a 60ton schooner, Olivia, in Port Dalrymple. The Olivia was key in the Lucas family goods-shipping enterprise until the late 1820s.[1]

Over time, the matriarch and a number of the Lucas children made either temporary or permanent moves to the Launceston area in Van Diemens Land. The family established a number of inter-related businesses, culminating in a regular trade between Van Diemens Land and Sydney Cove.[20][1]

In 1818 Nathaniel gained the contract for building St Luke's Church, Liverpool, designed by architect Francis Greenway. The two had a tempestuous relationship. Greenway had previously quarrelled with Lucas over the building of the Rum Hospital and in 1818 alleged that poor quality stone was used the foundations of the church, and that Lucas was a drunkard.[1]

On 5 May 1818 Nathaniel Lucas' body was found in the Georges River at Liverpool, his death having "proceeded from his own act, owing to mental derangement".[21] After Nathaniel's death The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser for Saturday 5 September 1818 advertised his wind mill in Liverpool for sale.[1]

John Lucas

John Lucas had been born on Norfolk Island on 21 December 1796 to Nathaniel Lucas and his wife Olivia (née Gascoigne). Both parents had arrived in the new colony as convicts on the First Fleet, and had married on Norfolk Island. He moved to Sydney with his family at the age of 9 and eventually followed in the footsteps of his father, apprenticing in carpentry and milling and pursuing various entrepreneurial ventures.[1]

In addition to building and operating three mills John is known to have owned an inn on George Street, Sydney, "The Black Swan", in addition to a warehouse and goods emporium at Liverpool.[1]

In 1817 John married Mary Rowley, the illegitimate daughter of wealthy land owner and Captain of the New South Wales Marine Corps, Thomas Rowley at St Philip's Church, Sydney. The marriage resulted in 10 children.[1]

Like many enterprising colonials, John's ventures were exposed to considerable risk. His substantial investment in his 1822 watermill on Harris Creek, known as the Brisbane Mill, in modern-day Voyager Point was hampered by a series of drought and flood. With an imperative to satisfy prominent creditors, Lucas attempted to supplement the Brisbane Mill with a new watermill, known as the Woronora Mill, in a remote area on the Woronora River near Engadine whilst he undertook significant repairs. The location of the two mills on tributaries of the Georges River may have allowed John to avoid paying duties on the flour he produced through shipping it in small boats to Liverpool, and using land transport to travel directly to the markets in Sydney, thereby avoiding the customs presence in Port Jackson.[22] Ultimately, due to a combination of climactic events, the sinking of his family schooner, Olivia in 1827, the death of his brother and occasional business partner, William Lucas, and increasing competition from steam mills, John was declared bankrupt in 1828 and his two mills were transferred to his creditors.[1]

In time, he recovered from his financial problems, largely due to a substantial inheritance received by his wife in 1832. He became a prominent landholder in the Burwood district and in 1841 built the dam for the Australian Sugar Company sugar mill at Canterbury.[23] He died in 1875 at Murrumbateman. John Lucas is remembered in the name of the suburb on the ridge above the Woronora Mill, known until recently as Lucas Heights. His name is also remembered in several place and street names at Richmond, Moorebank, Five Dock, Camperdown, Emu Plains, Panania, Lalor Park and Cronulla.[1]

John and Anne's eldest son, also named John Lucas, a builder and carpenter by trade, became a prominent Member of Parliament of New South Wales, serving part of his political career in Henry Parkes' Ministry. He was an advocate for free state schools, reformatories for wayward children, trade protection, and many other causes. He was one of the first to visit Jenolan Caves in 1861 and worked to have the area protected as a reserve and opened to the public. One of the largest caverns was named after him, and names such as Lucas Heights, various roads and other areas around NSW are sometimes attributed to him, or John Lucas Snr.[24][1]

Establishment of the Brisbane Mill

John Lucas built this first flour mill on Harris Creek (now known as Williams Creek) at Holsworthy in 1822. Whilst his 150-acre grant extended from the eastern bank of the creek, he chose to construct the mill on the western bank, which formed part of his father-in-law's adjacent grant of 700 acres, because it was better suited to the purpose. It was named the Brisbane Mill for Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane who had granted the land to John.[1]

The fairly remote location was referred to as Liverpool, in reference to the nearest township. The area was difficult to access overland as there was no bridge across the Georges River to this southern settlement until the building of the Liverpool Weir in 1836. Despite this, the flat and fertile area known today as Holsworthy was becoming recognised by remote farmers for its agricultural potential, and Mary and John joined early European settlers including their neighbour, Mary's brother, Thomas Rowley Jnr in the area.[1]

At the time of the 1828 Census John and Mary were recorded to be living at the Brisbane Mill with five of their children and nine assigned convicts.[25] In addition to the mill and its associated buildings and infrastructure, various domestic buildings, crops and livestock would have been necessary at this remote location to support such a household. Beyond milling, John and Mary identified other commercial opportunities at the site.[1]

An advertisement in The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser on Thursday 1 April 1824, p4, two years after the mill was built in 1824 the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, advertised both the milling function of the site and its use as a goods emporium:[1]

'BRISBANE WATER MILL,- The first Grant of His Excellency the present Governor of One Hundred and Fifty Acres of Land, for the Purpose of erecting a Water Mill, at Liverpool, has been completed by Mr, John Lucas, a native of the Colony. This Mechanic has finished the machinery, with the greatest accuracy; and now the Dam is completed, the Public are assured that Flour will be Sold as at low Prices as in Sydney; and I can confidently say, this Mill will not stand still for want of Water, when once the Dam is full. As hitherto the Mill was worked undershot, this waste, added to the uncommon drought, has caused the Mill to stand still. In the meantime Mr. Lucas will receive good Wheat free from smut at the Liverpool Warehouse, and pay for the same as fair as the Settler can sell in Sydney. The following Goods he offers for Sale :- Hyson and Hyson skin teas, sugar, soap, calico, prints, checks, cloth and handkerchiefs, of colours; crockery ware of sorts; hand, pit and cross-cut saws; files and nails, of sizes; rum, gin, wine and porter, in quantities not less than five gallons; with every other Sort of Good that is for Sale in Sydney. Orders punctually attended to; and as cheap supplied at my shop.

No. 72 George-street, Sydney. S. Levey.

N.B. - Good Bread for Sale, at the Brisbane Warehouse.'.[26][1]

The advertisement is listed by a Mr S. Levey. Solomon Levey was a prominent emancipist, philanthropist and merchant. With his partner Daniel Cooper he owned the Waterloo Warehouse, a very large 5 storey building located at 72 George Street Sydney. Amongst their significant portfolio of businesses and assets they had interests in numerous other mills in the Sydney area. The fact that Levey is the author of the advertisement suggests that he had a financial interest in the Brisbane Mill. It is possible that John Lucas had approached Levey for investment to adapt the mill and dam following the drought referenced in the article.[1]

In 1827 John sought to further diversify his business interests, advertising an additional business functioning at the site, The Brisbane Distillery.[27][1]

In addition to the drought John faced other significant financial pressures. The NSW Colonial Secretaries Index for 1824 reveals that had been unable to pay for his mill stones for the Brisbane Mill upon its construction in 1822, promising instead to pay in flour from his mill. At this time he was also on the list of defaulters in payment for assigned convict tradesmen.[1]

John Lucas' venture was also threatened by the unpredictable volatility of the price of wheat. A survey published in the Colonial Times in Hobart in 1831 gives the average monthly prices of wheat paid in Sydney in 1828. With variation between a minimum of 8 shilling 9 pence in January to 15 shillings in July per bushel, forecasting of profits would have been extremely difficult.[1]

When a significant flood destroyed his newly adapted mill and dam late in 1824 Lucas sought a second milling site in an attempt to supplement his losses, perhaps temporarily.[1]

Establishment of the Woronora Mill

John Lucas built his second mill on the Woronora River in 1825. As at the Brisbane Mill, John chose not to build this mill on his own 150 acre grant on the north western side of the river but instead built on crown land on the more suitable southern bank. In this extremely remote river valley there would have been no adverse consequences for this decision.[1]

At this time there were no substantial European settlements in the area. In light of this isolation it is said that prior to the 1830s Botany Bay, Broken Bay and their associated river systems were "havens for smugglers".[28] Some historians have speculated that Lucas may have chosen the location precisely to exploit its isolation, conducting illicit business such as smuggling illicit alcohol from the Five Islands district, using the mill as a legitimate front.[28][1]

The mill wheel and machinery would most probably have been made off site, disassembled and transported by boat to the mill site. Sydney's foundries were capable of producing castings such as wheel frames and gears up to 4 tons by 1823 but it is known that mill parts were also imported.[29] Getting these large items and the mill stones weighing approximately a ton each from boats to the site would have required a substantial labour force.[1]

Once constructed, a small work force would be required to operate the mill. Some clearing of the woodland was undertaken on the southern riverbank to allow for modest accommodation to be constructed and perhaps also limited livestock and cultivation of crops.[1]

Bankruptcy

On Monday 8 September 1828 The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser summoned John Lucas and all his creditors to a hearing of the Supreme Court of New South Wales to examine his bankruptcy. On Wednesday 17 September 1828 John Lucas was declared bankrupt in The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser with trustees appointed to deal with his estate.[1]

On Monday 5 November 1832 the Sydney Morning Herald, documented the transfer of both of John Lucas' mills and associated land to Solomon Levey. Levey's connection to John Lucas is unclear, as are the terms under which the mills became his property.[1]

Under new ownership the Brisbane Mill appears to have continued functioning in some capacity. Upon Levey's death in 1833 it officially passed to his business partner Daniel Cooper. On Monday 2 December 1839 The Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser declared the sale of flour, bran and pollard at Coopers Brisbane Mill in any quantity. It would seem that the mill buildings were utilised during this period as an emporium with the produce more likely to have been processed by Cooper's steam mills in Sydney.[1]

Little is known of the Brisbane Mill site until the 1860s when Joseph Pemmell was operating a paper and cardboard mill nearby. This was converted into a flour mill and, later a woolwash, run by Thomas Woodward before being destroyed by fire in the 1880s.[30] The four mills built successively on this site demonstrate the evolution of mill technology into the twentieth century and its application to different industries, giving a history of industrial and technological change through the nineteenth century.[1]

There is no mention of the Woronora Mill ever operating again. An advertisement dated Tuesday 14 March, 1843 describes the Woronora Mill as "being burnt down some years ago". On 18 May 1843 Major Sir Thomas Mitchell, then Surveyor General of New South Wales, wrote to the governor describing the "direct line of road to the Illawarra" that he had surveyed and was being built. The letter states, "It will be obvious from the accompanying map that the River Woronora which is navigable for boats to Lucas' Mill Dam'.[1]

The remote riverside location later attracted squatters who erected huts around the Woronora site into the mid twentieth century. These were converted into weekenders in the 1960s, but were later wiped out by bushfires. The local council, noting the hazardous environment demolished all structures and have maintained the site as a river reserve into the present.[1]

The Dharawal

The Dharawal people are the traditional custodians of the land extending from Botany Bay to the Shoalhaven River and Nowra and inland to Camden. For millennia, natural resources supplied all their material needs. The land around the Georges River and its tributaries provided water, food and shelter. The streams and swamplands offered a variety of food. The forest lands sheltered possums, lizards, kangaroos and wallabies and there were roots, berries and seeds to gather. Birds also provided meat and eggs. Along the Georges River, sandstone eroded, forming rock overhangs which provided shelter. The walls of these shelters were often decorated with images and hand stencils outlined in red ochre, white clay or charcoal. Evidence of their tracks, camps and significant sites are scattered across the region, and continue to have meaning for the Dharawal people today.[1]

As the colonial settlement expanded into Dharawal country there was notable conflict. In spite of this, some Europeans formed ties with the local Aboriginal community. Figures such as Charles Throsby were persistent critics of European treatment of local Aboriginal people. Others, such as Hamilton Hume and John Hume recognised that the Aboriginal community's knowledge of the land made them resourceful companions in a new and foreign environment (Campbelltown City Council).[1]

The Holsworthy area is also noted to be of traditional significance to the Dharug and the Gandangara.[1]

There is no record of John Lucas' interaction with Aboriginal peoples, though it would have been considerable.[1]

Description

Lucas Watermills are located across two separate archaeological sites. These sites, located in south west Sydney, comprise the remains of the Brisbane Mill, and the Woronora Mill together with associated infrastructure including dams, flour-processing machinery and accommodation.[1]

The Brisbane Mill

.jpg.webp)

The site is in a swampy tidal area on Williams Creek. The surrounding vegetation consists of woodland with casuarinas and mangroves. There is a trail that provides public access from Creekwood Reserve. A large number of tracks run through the site on the southern bank of the river. The river is navigable for small boats to approximately 10m below the dam site.[1]

A series of axe grinding groves at the northern extent of the site demonstrates the use of the site by the Dharawal Aboriginal people. There is a mixture of industrial remains on the site. A substantial rock cut channel and other rock work exhibit pick marks indicating construction in the early nineteenth century. The remains of two rock and concrete dams are visible on the southern edge of the site. The visible remains suggest that the mill was located on the western bank of the creek.[1]

There are 4 types of visible features:

- Cuts in the bedrock, made with rock picks. These are the most common type of feature.

- Holes drilled into the rock, all of approximately 50mm diameter.

- Stone and cement dam walls. The type of cement and stone indicates that some of the walling is related to Lucas' 1825 mill, other walling relates to the later paper and woollen mills which operated on site in the latter nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

- A 12000mm long, 1000mm wide trench cut through rock, which is likely to have been the mill race.[1]

The Woronora Mill

.jpg.webp)

The site is on the Woronora River in a steep valley of rocky, open woodland. It can be accessed on food via a fire trail upstream at the Pass of Sabugal. A large Water Board supply pipe from Woronora Dam runs above the site on the southern bank of the river. The river is navigable for small boats to approximately 60m west of the site. The visible remains suggest that the mill was located on a relatively level shelf of bedrock on the north eastern bank of the river.[1]

There are 3 types of visible features:

- Cuts in the bedrock, made with rock picks. The largest of these cuttings could support a timber beam up to 450mm wide, a suitable support for a bearing of the water wheel.

- Holes drilled into the rock, all of approximately 50mm diameter.

- Remnant cement which can be used to trace the line of the mill dam.[1]

Condition

Materials at the site of the Brisbane Mill are likely to have been reused or scrapped by successive occupants up to the 1920s.[1]

Fires and floods since the abandonment of the Woronora Mill have removed most of its structure however archaeological remains may include evidence of structures that controlled water flow, the waterwheel, mill machinery, ancillary buildings and associated infrastructure.[1]

Heritage listing

.jpg.webp)

The Lucas Watermills Archaeological Sites, built by the prominent colonial miller, John Lucas, are of historical significance as two of the earliest surviving watermill sites in the state. Their association with the builder's father, the First Fleet Convict, Nathaniel Lucas, who built 6 of the first mills in the colony, is of state significance. They were constructed with convict labour and, together, show Lucas' attempts to continuously adapt his milling strategy in the face of environmental challenges. The adaptation of technology across the two sites, and Lucas' ultimate failure to make this milling venture economically viable demonstrates the difficulty of food production, in particular the conversion of grain to flour in the new colony. They demonstrate the early development of the milling industry as well as the transport networks that supplied the mills, distributed their products and integrated their operations. The story of Lucas' watermills is also of state significance for its ability to communicate the entrepreneurial aspirations of 1820s New South Wales colonials.[1]

.jpg.webp)

The Lucas Watermills Archaeological Sites were listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 30 August 2017 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

Lucas' Mills are of historical significance as two of the earliest surviving industrial archaeological sites in the state. While altered, the immediate sites continue to reflect the remote character of the places as they were when the mills were first constructed; The mills and the machinery are of significance as they were constructed and operated with the use of convict labour; The sites reflect how, in the 1820s, early colonial entrepreneurs used the fertile lands along the waterways of the Georges River for transport and commerce, closely connecting the area with Liverpool, Botany Bay and Sydney; The locations chosen by Lucas on tributaries of the Georges River are of state significance for telling the story of early attempts by the government to impose tariff policies on flour production and the way in which the industry adapted in response; The adaptation of machinery and facilities across the two sites (including a second dam and conversion of undershot to overshot milling at Brisbane Mill), and Lucas' ultimate failure to make his milling venture economically viable demonstrate the difficulty of food production, in particular the conversion of grain to flour in the new colony. Across Australia there were issues in adapting technology to a new physical and social environment and in implementing the technology with limited skilled labour.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

The mills are associated with their builder, the prominent miller John Lucas and through him his father Nathanial Lucas; Nathaniel Lucas (1764–1818) was a convict transported to Australia on the First Fleet. He was appointed Master Carpenter at Norfolk Island in 1802 and later, Superintendent of Carpenters in Sydney. He built six of the first successful mills in the colony including the 1797 mill at Millers Point, and major building projects such as the Greenway designed Rum Hospital (1811) and St Luke's Anglican Church, Liverpool (1818). He trained his sons in his trade; The sites are also associated with their later owners, Solomon Levey and Daniel Cooper, who were highly successful entrepreneurs in the early colony and made several ventures in the milling industry, notably running one of the earliest steam mills; The Brisbane Mill was named for Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane (1773–1860), who granted the land to Lucas.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

The two mills and the connecting waterways allow for examination of the cultural maritime landscape of the 1820s; They demonstrate the early development of the milling industry as well as the transport networks that supplied the mills, distributed their products and integrated their operations; Visible surface remains of the mills include cuts in the bedrock made with rock picks, holes drilled into the rock and stone and cement dam walls and channels. These indicate the locations and functions of the mill dams, wheel pits, races, sluices and other structural rock, which, together, demonstrate the evolving understanding of water utilisation along these particular bodies of water.[1]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

The archaeological resource may include structures that controlled water flow, mill machinery, buildings for processing and storage and associated infrastructure including domestic dwellings; The sites and their interrelationships provide a unique opportunity to understand the industrial development of milling and food production more broadly in the early colony; The continuation of use of the Brisbane Mill site for the paper and woollen industries (c. 1870s-1920s), with new dams and a steam mill demonstrate the evolution of milling technology over a century.[1]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Remnants of other water driven flour mills exist elsewhere in the state, however these are some of the earliest and are the only substantial remains in the Sydney metropolitan area, having been relatively undisturbed.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

Lucas' sites and their evolution provide good representative examples of early milling infrastructure in NSW which required much experimentation to meet local environmental and logistical constraints and were largely ultimately unsuccessful.[1]

See also

References

- "Lucas Watermills Archaeological Sites". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01989. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - "Woronora's historic Lucas Watermill site up for heritage listing". St George and Sutherland Shire Leader. 27 October 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- Pearson 1996:56

- Birmingham, Jack and Jeans 1983:27

- Tratai 1994:14

- Tratai 1994:19 - 22

- Birmingham, Jack and Jeans 1983:32

- Tatrai 1994:24-29

- Tratai 1994:19, 30

- Tatrai, pp30-31

- Farrer 2005:17

- Tatrai 1994:32

- Birmingham, Jack and Jeans 1983:38

- Tatrai 1994:35

- Birmingham, Jack and Jeans 1983:45

- Connah 1988:133

- Farrer 2005:18

- Herman 2006- 2012

- Ancestry.com 2006-2012

- Kate Matthew 2011

- Herman 2006-2012

- Jackson, Forbes, 2012

- SMH, Friday 2 February, 1883, p.5

- Helen Lucas, 2011

- Curbie 2004

- The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser on Thursday 1 April 1824, p4

- (The Australian, 27 July 1827, p. 2)

- Curby 2004: 13

- Pearson 1996:57

- (Liverpool City Council)

Bibliography

- Birmingham, J., Jack, I., Dennis, J. (1983). Industrial Archaeology in Australia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Campbelltown City Council. Campbelltown's Aboriginal History: An insight into the first peoples of our region.

- Connah, G. (1988). 'Of the hut I builded': The Archaeological History of Australia.

- Curbie, P. (2004). Lucas' Mill.

- Day, D. (1992). Smugglers and Sailors, The Customs History of Australia 1788-1901.

- Department of Urban Affairs and Planning (1995). Shipwreck Atlas of New South Wales.

- Farrer, K. (2005). To feed a nation: a history of Australian food science and technology.

- Fletcher, B. H. Rowley, Thomas (1748-1806).

- Forbes, P., Jackson, G. (2013). The Watermills of John Lucas: Part 3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Forbes, P., Jackson, G. (2012). The Watermills of John Lucas: Part 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lucas, H. (1997). Lucas Family.

- Matthew, K. (2011). Lucas, Olivia.

- NSW Government Gazette (2017). "NSW Government Gazette" (PDF).

- NSW State Records (1827). Surveyor General's Crown Plans, SR2733.

- Pearson, W. (1996). Water Power in a Dry Continent: The Transfer of Watermill Technology from Britain to Australia in the Nineteenth Century.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Lucas Watermills Archaeological Sites, entry number 01989 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Lucas Watermills Archaeological Sites, entry number 01989 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.