Luca Arbore

Luca Arbore or Arbure (Old Cyrillic: Лꙋка Арбꙋрє;[1] Renaissance Latin: Herborus[2] or Copacius;[3] died April 1523) was a Moldavian boyar, diplomat, and statesman, several times commander of the country's military. He first rose to prominence in 1486, during the rule of Stephen III, Prince of Moldavia, to whom he was possibly related. He became the long-serving gatekeeper (or castellan) of Suceava, bridging military defense and administrative functions with a diplomatic career. Arbore therefore organized the defense of Suceava during the Polish invasion of 1497, after which he was confirmed as one of Moldavia's leading courtiers.

Luca Arbore | |

|---|---|

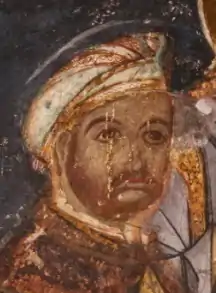

Votive portrait in Arbore Church, ca. 1504 | |

| Gatekeeper of Suceava | |

| In office September 14, 1486 – March 25, 1523 | |

| Personal details | |

| Died | April 1523 Hârlău |

| Nationality | Moldavian |

| Spouse | Iuliana |

| Nickname(s) | Herborus Copacius Luca the Vlach? Ulyuka? |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1486–1523 |

| Rank | Spatharios (intermittently) Hetman (attributed posthumously) |

| Commands | Moldavian military forces |

| Battles/wars | Polish–Moldavian Wars (1494, 1502, 1505–1510) Battle of Ștefănești (1518) |

As a military commander, Arbore participated in Moldavian's occupation of Pokuttya in 1502. He is tentatively identified as "Luca the Vlach", who served Stephen on crucial diplomatic missions to Poland and the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Also a great landowner and patron of the arts, Arbore commissioned the painting of Arbore Church. The building is one of the eight Moldavian churches on the UNESCO World Heritage list.

Gatekeeper Arbore was identified, possibly erroneously, as a pretender to the Moldavian throne in 1505. He still served Stephen's son Bogdan III, who needed his services in particular during the Moldavian–Polish border clashes of that year. He maintained his position despite suffering defeat, and, possibly as a hetman, went on to serve as tutor of Bogdan's orphaned son, Stephen IV "Ștefăniță". As such, he aligned the country with Poland and waged war against the Crimean Khanate (a proxy for the Ottoman Empire), winning a major victory at Ștefănești in August 1518.

In 1523, the prince accused the Arbore males of insubordination, and had most of them executed. Although the original accusation was probably spurious, the execution itself sparked an actual boyar revolt. The Arbore line was largely extinguished in 1523, but survived mainly through female descendants; the name was eventually reused by people who were distantly related to the original family, including, in the late 19th-century, the scholar-politician Zamfir Arbore. By then, the gatekeeper had also been recovered as a symbolic figure in the literature of authors such as Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, Mihai Eminescu, and Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea.

Biography

Early life

Born at an unknown date,[4] Luca was the son of Cârstea Arbore, who served as pârcălab of Neamț Citadel in the 1470s, and his wife Nastasia.[5] Various researchers argue that Cârstea, possibly known as Ioachim in some sources, was brothers with Stephen III—making Luca eligible for the princely throne.[6] Luca also had a brother, the Pitar Ion, and a sister, Anușca.[7] Anușca went on to marry the boyar Crasnăș. The latter's father, also named Crasnăș, was famous as a dissenting boyar, having reportedly deserted Stephen III during the Battle of Baia.[8] Cârstea himself remained loyal to the prince down to his death. He was killed by the invading Ottoman army during the invasion of 1476, either at Vaslui or in front of Neamț Citadel.[9]

Luca's main office was gatekeeper of Suceava from September 14 (New Style: September 24), 1486.[10] The attributes of this office were greatly expanded by Stephen: it implied command offices in the Moldavian military forces and diplomatic functions, obliging Arbore to become a polyglot.[11] By 1500, he was fluent in Church Slavonic, Polish, and Latin.[12] From 1486, Stephen granted his gatekeeper half of Țăpești village, on the Lozova River (the other half was awarded to Duma Burdur in 1499).[13]

In parallel, Arbore was the squire of an eponymous estate in Bukovina, and of Șipote, in Iași County. He became ktitor of churches, dedicated to Moldavian Orthodoxy, in both localities.[14] He purchased Arbore, including the present-day city of Solca and communes of Botoșana and Iaslovăț, in March 1502, developing it into his main demesne—favored, with Șipote, because it was closest to Stephen's preferred courts (Suceava and Hârlău).[15] Folklore records that Arbore used Polish and Ottoman prisoners of war as his laborers, forcing them to quarry stone from Solca River.[16] From his mother Nastasia, the gatekeeper also inherited the Bessarabian village of Hilăuți.[17] Tradition further attributes him ownership of Hrițeni, in northern Bessarabia.[18]

Arbore married a lady Iuliana. One account suggests that she was the daughter of comis Petru Ezăreanul of Tutova County, also killed in the war of 1475; this remains disputed.[19] They had at least four male children: Toader, Nichita, and Gliga, and Ioan, the latter of whom did not survive into adulthood.[20] Some records attest a fifth son, Rubeo Arbore.[21] Of his seven daughters, Ana married the great comis Pintilie Plaxa. Another daughter, Marica, was the mother of Marica Solomon, wife of the vistier Solomon.[22] Finally, a daughter Sofiica was traditionally believed the wife of a great vistier, Gavril Totrușan (or Trotușan). Later researchers asserted that her husband was another vistier, Gavril Misici.[23] However, according to scholar Adrian Vătămanu, she may have been Totrușan's second wife, and Totrușan himself may have been a Misici.[24] Arbore also had a nephew, Dragoș, whom he groomed for the office of Suceava gatekeeper[25] and to whom he donated an estate in Țăpești.[26]

As a diplomat, Arbore carried out several diplomatic missions in Poland and the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Historian Valentina Eșanu believes that Arbore is Luka voloshanin or Luca walachus ("Luca the Vlach"), mentioned by several sources as leading Stephen's embassies to these two countries. This would mean that in 1496–1497 he accompanied the Muscovite envoy Ivan Oscherin, who was traveling back and forth between Moscow and Moldavia. This mission was part of a series of high-level contacts between Moldavia, Moscow, and Lithuania, persuading Alexander Jagiellon, who was only Grand Duke of Lithuania at the time, to withdraw from an alliance with Poland.[27]

In 1497, as Poland invaded Moldavia and besieged Suceava, Arbore reportedly organized a "heroic defense" of the capital.[28] The events at the brought Arbore into direct contact with the Polish king, John I Albert, as mentioned years later by Albert's brother, Alexander Jagiellon. Alexander's letter also confirms that Albert viewed Arbore as a possible contender for the Moldavian throne; in a different chronicle, the defenders are said to given the following reply to Albert: "Know that we will not betray our lord and his castles to you, for our lord, Prince Stephen, is in the field with his army; if you so desire, go and defeat him, and then his castles and the entire country will be yours."[29] The same chronicle describes a meeting between Albert and Arbore outside the castle walls, a few days into the siege. Albert, thinking that Arbore might have princely aspirations, proposed to the gatekeeper that he handle him Suceava and receive support for obtaining the throne. Arbore refused; Albert then tried to capture Arbore, but the latter managed to retreat into the citadel.[30]

Prominence

In late 1497, the itinerant Oscherin and Luka voloshanin were robbed in Terebovlia by a band of Crimeans and Cossacks, allegedly led by Prince Yapancha. The incident prompted Stephen to demand reparations from Meñli I Giray, but these were never fully returned.[31] In 1501, as tensions between Poland and Moldavia were being reignited, Arbore traveled to Halych and informed the local starosta that Moldavia intended to annex that city, and possibly other parts of the Ruthenian Voivodeship as well. It is however not known if the visit was an official diplomatic mission or Arbore's own initiative.[32] That year, a number of Muscovite envoys were detained in Moldavia by Stephen, who wanted safety guarantees for his daughter Olena, imprisoned alongside his grandson Dmitry. The diplomats were released in June 1502, and accompanied back to Moscow by the Moldavians Doma and Ulyuka—according to Eșanu, these may be boyars Duma Burdur, or Duma Vlaiculovici, and Arbore.[33]

In the fall of 1502, although Alexander Jagiellon had taken the Polish throne from his brother, Poland and Moldavia were again at odds with each other. In that context, Arbore had a prominent role in the occupation of Polish region of Pokuttya. He ordered his own tombstone at around the same time, possibly as a precaution.[34] During the campaign, Arbore again met the starosta of Halych, who asked him about the destruction of a castle by the Moldavians. Arbore gave a firm reply, meant to be heard by Alexander Jagiellon—it suggested that his lord, Stephen III, did not wish to have any castles near his border, save the castle of Halych.[35] If the identification of Luca walachus is correct, in November 1503 Arbore also led a Moldavian delegation to Lublin, trying to reach an understanding over Stephen's annexation of Pokuttya.[36]

Arbore was also integrated on the Boyar Council in 1486, but only returned there in 1498, possibly because he was too often absent from the country on diplomatic assignments.[37] According to historian Virgil Pâslariuc, he was co-opted there because he supported Stephen's co-ruler and designated successor, Bogdan III, whose claim to the throne was contested by his brothers; and also because he was a distinguished warrior.[38] During the final years of Stephen III's reign, Arbore and Ioan Tăutu became increasingly influential, taking on more and more attributes; by 1503, Arbore had also risen through the Boyar Council, being listed there as the eighth most important boyar.[39] For a while, he was the country's spatharios, or military commander.[40]

In 1504, with Stephen III dead, Arbore was allegedly a pretender to the throne, although he continued to serve as courtier of the recognized successor, Bogdan.[41] This account, contested by several historians, is based on Alexander Jagiellon's letter, which also claims that Arbore narrowly escaped an assassination attempt.[42] According to Nicolae Iorga, the whole episode, as narrated by the source, is "hard to believe" and "confusing".[2] In 2013, Liviu Pilat argued that the whole controversy about Arbore's claim to the throne stems from a misreading of Alexander's letter, which refers only to the events of 1497.[43] Pâslariuc proposes that Bogdan used Arbore, his loyalist and mentor, to solidify his legitimacy.[44] He also notes that Bogdan punished his nephew Dragoș, who had "ruined a very expensive cannon", by confiscating one of his estates. This was an example of the prince "confronting the great families", with which he was otherwise at peace.[45]

Arbore led troops in combat during the new Moldavian–Polish clashes of 1505, prompted by the failed marriage arrangements between Bogdan and Elizabeth Jagiellon. Reportedly, he was present at the Moldavian sieges of Kamianets and Lviv.[46] The Poles responded twice, anticipating Arbore's counterattacks and defeating the Moldavian troops on both occasions, which prompted Bogdan to sue for peace.[47] Some of Arbore's other work concentrated on erecting the church of Arbore, which was finished in 1502, and to which he donated an Acts of the Apostles in 1507.[48] The frescoes, completed in 1504, are a synthesis of Renaissance and Byzantine art,[49] noted for the usage of Gnostic and Bogomil symbols in an otherwise Orthodox context.[50] Church historian Mircea Pahomi advances the hypothesis that Arbore used Italian stonemasons and painters for at least some of this work.[51] His and his wife's coats of arms, displayed on the central shrine, are among the very few examples of classical Moldavian heraldry.[52]

Regency and downfall

Bogdan was an ailing prince, incapable of fulfilling his duties toward the end of his life; alongside Totrușan, Arbore again took hold of the actual government.[53] The throne went to Stephen IV, a minor (11-years-old at the time).[54] Arbore became the ruler's tutor and, as such, the country's éminence grise.[46][55] His estate increased in 1516 with the purchase of Soloneț from the boyars Hanco,[56] eventually comprising 39 separate domains, including Mount Giumalău.[57] Arbore held the office of gatekeeper to March 15 (March 25), 1523;[58] he is also listed as a hetman by the chronicler Macarie, but, Eșanu writes, this office had not yet been introduced at the Moldavian court.[59] Similarly, Pahomi notes that the title of hetman is "wrongly applied" to Arbore, who never held it.[60]

During this interlude, Moldavia's foreign policy shifted, and Stephen signed an alliance with the new Polish monarch, Sigismund I.[61] Arbore, identified by medievalist Ilie Grămadă as the leader of a Polonophile party, negotiated advantageous terms: until Polish troops had entered her territory and provided for her security, Moldavia was not required to either assist Poland or cease paying her debts to the Ottoman Empire.[62] Overall, his policy on the Ottoman issue is described by Pahomi as "active neutrality".[63] Nonetheless, the policy change, which opened the way for Moldavia's participation in a planned crusade organized jointly by the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of France,[64] upset Moldavia's relations with the Ottomans and the Crimeans. In August 1518, Mehmed I Giray sent Crimean troops into Moldavia. These were met outside Ștefănești by a well-prepared Moldavian force, led by Arbore; there, Mehmed suffered a massive defeat, with many of his troops drowning in the Prut River.[65]

Military historian Mihai Adauge describes Arbore as a "great strategist" and "fearless patriot", on par with Stephen III.[66] Nevertheless, by 1523 the Arbore males had encountered his prince's wrath, being formally charged with hiclenie (treason).[67] The parish chronicle of Solca noted in the 1880s that "no Moldavian chronicle" specified what crime Arbore had actually committed.[68] As read by Pahomi, the prince's decision reflected cleavages within the Council, inherently linked with the Polish–Ottoman issue. The "old boyars" fell out of favor; a postelnic Cozma Șarpe Gănescu, confronted with similar charges, escaped to Poland.[69] According to Vătămanu, Stephen IV was angered that Sigismund's court still hosted pretenders to the Moldavian crown. Although Arbore may have agreed with the prince on this point, and also favored a disengagement from the Polish alliance, "it appears that the Polish emissaries would not let him."[70]

Luca was decapitated in April at the princely court in Hârlău.[46][71] Toader and Nichita Arbore were reportedly put to death, by strangling[72] or decapitation,[73] during the following month. According to one tradition, one of them may have actually been dead by that time, accidentally killed during a hunting trip.[74][75] The family residence at Arbore–Solca was confiscated by the ruler, and became state land.[76] Arbore's grave remains undiscovered, but one theory is that his body was stolen by his partisans and secretly buried at Solca.[46]

The execution episode is credited with sparking a boyar revolt,[77] which happened in September 1523.[78] Grămadă also notes that Arbore's death signaled another foreign policy change, with Poland fearing a Moldavian–Ottoman rapprochement—despite the Moldavian–Ottoman clash at Tărăsăuți.[79] The prince, who maintained hold of the country while at war with Polish-aligned boyars and Wallachia, appointed a new administration, comprising Totrușan, and, as the new gatekeeper of Suceava, the boyar Petrică.[80] Totrușan is nevertheless listed among the boyars who took up arms, supporting the pretender Alexandru Cornea.[81] The movement was finally repressed in blood. Much of the old elite was forced into exile, with some captives executed by the prince at his residence in Roman.[82]

Luca's wife Iuliana had probably died before 1523.[83] Rubeo Arbore, allegedly one of her two surviving sons, took hold of two Moldavian bombards and surrendered with them to the Kingdom of Hungary; his sister Sofiica and her husband Gavril also left the country, settling in Poland.[84] Gliga Arbore disappeared from records at a later date. According to various researchers, he fled into Lithuania, possibly as late as 1545.[85] Genealogist Octav-George Lecca argues that the fugitive was another Gliga Arbore, collaterally related to Luca, and describes the flight as an eloping to Poland with two nuns.[86] The Arbore family survived through Luca's female descendants[87] and, according to Lecca, also other close relatives.[88] Daughter Ana Plaxa recovered possession of the Arbore manor in circa 1541, when Petru Rareș had taken the Moldavian throne. She commissioned master Dragosin Coman to repaint the manorial church, which had been damaged by an Ottoman invasion in 1538, and, dying childless, bequeathed the place to her niece Parasca Udrea.[89] A granddaughter, Anghelina, married a diplomat of Princes Rareș and Iacob Heraclid, Avram Banilovschi.[90] A Mihu Arbore was recorded as hetman during the reign of Rareș; in 1538, he changed sides and offered his support to Stephen V "Locust", only to take part in a conspiracy against the latter that ended with the prince being assassinated in Suceava.[91]

Legacy

Arbore survivals

The Udreas, acting as Arbore successors, obtained other parts of the Solca estate in 1555.[92] However, the then-ruler of Moldavia, Alexandru Lăpușneanu, staged another clampdown against the high-ranking boyars, and Plaxa possibly died during the events.[93] Marica Solomon was still alive in 1583, when she had withdrawn to a convent; she and Grigore Udrea fought over various family assets, with Udrea formally accused of forgery.[94] Ana Plaxa, also a nun, was cared for by the Udrea family.[95] By 1598, the dispute had been settled in favor of the Udreas, who then sold their land in Solca to the Movilești family, which transferred it to Sucevița Monastery. The Solomons received as compensation the fief of Stănilești.[96]

At least from 1606, the Ponici family of Bessarabia was also registered as descending from one of Luca Arbore's daughters, Stanca. This branch intermarried with the descendants of gatekeeper Petrică, which included Prince Ștefan Petriceicu.[97] The Udrea inheritance went to a Toader Murguleț, who supported dowager princess Elisabeta Movilă in her war with Ștefan Tomșa. When the latter took the throne, he confiscated Solca and donated it to the eponymous monastery.[98] In 1620 Luca's reported heirs included his daughter Marica's daughters (or granddaughters), Tofana and Zamfira, and Anghelina's daughter, Nastasia.[99] They tried but failed to secure ownership of Solca, which had remained in the care of Solca Monastery.[100] By 1644, another one of Luca's great-granddaughters, Magda, was married to Onciu Vrânceanu, the vistier of Prince Vasile Lupu.[101]

The core estates of Arbore and Solca were reportedly first devastated by various raids in the 17th century, in particular by Tomșa's civil war and the Polish expedition of 1683.[102] As "Bukovina", the area fell under the Habsburg monarchy, and then the Austrian Empire. This new administration passed the core Solca estate into a church land fund, then rented it, cementing its designation as Arbore (also Arbure or Arbura).[103] The locality became a target for German immigration from Bavaria.[104] By 1860, the manor had been looted and vandalized, with some of its discarded masonry used for a belfry (a feature not present in the original building); the coat of arms of Moldavia, displayed on its walls, was covered with mortar.[105] The cellar and tunnel still survived, and were used as a hideout by the haiduc Darie Pomohaci.[106]

An incomplete inscription suggests that some Arbores had by then settled in Poland, and were serving in the Commonwealth Army early in the 18th century.[107] Historian Alexandru Furtună also proposes that, by 1746, some Arbores had merged with a branch of the Cantacuzino family and with the boyar clans of Bantăș and Prăjescu. That year, the other three families divided Hilăuți into respective fiefs.[108] As Lecca notes, those who still bore the Arbore surname descended the social ladder, becoming free peasants or burghers by 1700—although, a century later, a Dumitru Arbore was attested with the rank of paharnic. His two daughters married respectively into the Kogălniceanu family and the Ralli clan.[109] The scholar and revolutionary Zamfir Ralli inherited the surname Arbore from a relative that had been adopted by that family, and which may descend from the 16th-century gatekeeper.[110] Pâslariuc noted, in 1997, that "the name of the Arbure family lives on to this day."[111]

In culture

Various posthumous sources maintained a respectful image of the alleged rebel. The Polish chronicler Bernard Wapowski described him as a "strong and great man".[112] According to art historian Emil Dragnev, the Suceava Church of Saint George, painted during the rule of Stephen's half-brother and successor Petru Rareș, may give clues that Arbore's execution was already seen as a serious transgression. The frescoes give a usually prominent role to Naboth, falsely accused and murdered by the unjust Ahab.[113] Of the Moldavian chroniclers which covered the event, Macarie, an official historian, was blunt in "never giving hint that there was something unjust about [Arbore's execution]"; writing much later, the Polonophile boyar Grigore Ureche hinted that the prince had been flattered and misled by Arbore's personal enemies.[114] Ureche also argues that Luca was not put on trial for the accusations made against him, nor were any of the claims proven, although, according to Dragnev, Ureche's own claim is not necessarily backed by evidence.[115]

In 19th-century Moldavia and the successor Kingdom of Romania, Arbore was also recovered by literature, appearing early on as an heroic figure in Constantin Stamati's poem, Santinela,[116][117] and being portrayed in prose works by Constantin Negruzzi.[46] In the 1860s, the Bessarabian Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu made him a key figure in the novella Ursita, loosely based on the conflict between Stephen IV and Șarpe Gănescu. Here, Arbore is shown advising Șarpe to flee the country, and is then imprisoned as revenge.[118] Another episode shows Arbore and Stephen III chatting about Renaissance magic.[119] Hasdeu also began writing a novel Arbore, which he never finished.[120] During that period, Mihai Eminescu sketched the novel Mira, named after a fictional daughter of the gatekeeper. Arbore himself is present in the work, standing for the "glorious past" of Stephen III's reign, against the decadence of Stephen IV. Stephen IV falls in love with Mira, but eventually kills her father.[121]

Published a generation later, the play Apus de soare, by Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea, also has Arbore for a main protagonist.[122] In Delavrancea's subsequent work, Viforul, Arbore is again the central figure—although, according to critic Eugen Lovinescu, his presence is superfluous, epic rather than dramatic.[75] Arbore's alleged scheme is taken for granted by the dramatist, and depicted as a grave error of judgement.[123] The hunting trip episode is depicted as an early stage in the conflict between the prince and the gatekeeper, leading to the deliberate murder of Arbore junior, here named Cătălin.[75]

The Ureche account was repeated by the Bukovina Minister Ion Nistor during the 1924 commemoration of Arbore's death—six years after Bukovina's integration into Greater Romania. Nistor added that Arbore was a "clean soul" and "true martyr" of the Romanian Orthodox Church, before whom Moldavians knelt.[46] As argued in 2001 by scholar Lucian Boia, Arbore's treatment in Romanian historiography went through two distinct phases. Before the onset of Romanian communism, historians generally described as his execution as "unjustified", and listed it as one of Stephen IV's shortcomings. During communism, the prince was lauded for his dealing with "the betrayers of the country".[124] Restored at later intervals, the Arbore church is, as of 2014, one of eight Moldavian churches on the UNESCO World Heritage list.[125]

Notes

- Constantin Velichi, "Documente inedite de la Ștefan-cel-mare la Ieremia Movilă", in Revista Istorică, Issues 7–9/1934, p. 245

- Nicolae Iorga, "Cronică", in Revista Istorică, Issues 7–9/1934, p. 291

- Pâslariuc, pp. 8, 15

- Eșanu, p. 136

- Pahomi, pp. 85, 90; Stoicescu, p. 261

- Eșanu, p. 136. See also Pâslariuc, p. 4

- Stoicescu, pp. 261, 267

- Stoicescu, pp. 266–267

- Eșanu, p. 136; Pahomi, p. 85; Pâslariuc, p. 8

- Pâslariuc, p. 8; Stoicescu, p. 261

- Eșanu, p. 136

- Eșanu, p. 137

- Chelcu & Chelcu, p. 153

- Apetrei, pp. 126, 181–184; Pahomi, p. 85; Stoicescu, p. 261

- Pahomi, pp. 83–85, 102

- Pahomi, p. 86

- Furtună, pp. 168, 170

- Lefter, p. 291

- Maria Magdalena Székely, "«Acești pani au murit în război cu turcii»", in Analele Putnei, Vol. II, Issues 1–2, 2006, p. 33. See also Stoicescu, p. 271

- Pahomi, pp. 90, 94, 96, 97

- Pahomi, p. 95

- Pahomi, pp. 90–91, 94–95, 97, 101, 102; Stoicescu, pp. 261–262, 323, 325, 446. See also Schipor, pp. 220, 222; Vătămanu, pp. 303–305, 309, 315

- Pâslariuc, p. 9

- Vătămanu, pp. 304–306, 308–309, 315–316

- Pâslariuc, pp. 11, 12–13

- Chelcu & Chelcu, p. 153

- Eșanu, pp. 137–138, 140

- Adauge, p. 83; Pâslariuc, pp. 3, 8. See also Pahomi, p. 84

- Pilat, p. 45

- Pilat, p. 45

- Eșanu, p. 138

- Eșanu, p. 138

- Eșanu, pp. 138–139, 141

- Pâslariuc, p. 3

- Pilat, p. 47

- Eșanu, pp. 137, 139, 141

- Eșanu, pp. 136–137, 138

- Pâslariuc, pp. 2–3, 8

- Eșanu, p. 136

- Vătămanu, p. 303

- Eșanu, pp. 136, 138; Pâslariuc, pp. 4–6, 8; Pilat, passim

- Pâslariuc, pp. 4–5; Pilat, passim

- Pilat, passim

- Pâslariuc, pp. 4–7, 8

- Pâslariuc, pp. 12–13

- Ion Nistor, "La mormântul lui Luca Arbore", in Cultura Poporului, August 24, 1924, p. 3

- Pâslariuc, pp. 15–16

- Apetrei, p. 180; Pahomi, p. 98

- Apetrei, p. 181; Pahomi, p. 92

- Ștefan Starețu, "Ortodoxia și dinastia sfântă în Balcani în secolele XIV–XV", in Revista STUDIUM, Vol. VIII, Supplement 1/2015, p. 44

- Pahomi, pp. 91–92, 96

- Dan Cernovodeanu, Știința și arta heraldică în România, pp. 170, 378–379. Bucharest: Editura științifică și enciclopedică, 1977. OCLC 469825245

- Vătămanu, p. 309

- Lecca, p. 148

- Adauge, pp. 79, 83; Boia, p. 196; Dragnev, p. 57; Lecca, p. 8; Pahomi, pp. 84, 90; Schipor, p. 222; Vătămanu, p. 309

- Chelcu & Chelcu, p. 110

- Pahomi, p. 85

- Stoicescu, p. 261

- Eșanu, p. 140

- Pahomi, p. 102

- Adauge, pp. 80–81; Grămadă, pp. 42–43

- Grămadă, p. 42

- Pahomi, p. 84

- Grămadă, pp. 42–43

- Adauge, pp. 80–83

- Adauge, p. 83

- Dragnev, pp. 57–58; Pahomi, p. 85; Schipor, p. 222; Stoicescu, pp. 261–262

- Schipor, p. 222

- Pahomi, p. 85

- Vătămanu, p. 309

- Dragnev, p. 57

- Dragnev, p. 57

- Lecca, p. 8; Pahomi, p. 94; Schipor, p. 220

- Vătămanu, p. 309

- Eugen Lovinescu, Istoria literaturii române contemporane, p. 301. Chișinău: Editura Litera, 1998. ISBN 9975740502

- Pahomi, pp. 85, 102; Vătămanu, p. 306

- Pahomi, p. 85; Stoicescu, p. 261

- Schipor, p. 222; Vătămanu, pp. 310, 320

- Grămadă, p. 45

- Pâslariuc, p. 9. See also Lefter, p. 299

- Vătămanu, pp. 310, 320

- Pahomi, p. 85; Schipor, p. 222; Vătămanu, p. 310

- Pahomi, pp. 89–90

- Pahomi, p. 95

- Pahomi, p. 95. See also Stoicescu, p. 261

- Lecca, p. 9

- Schipor, p. 222; Stoicescu, pp. 261–262

- Lecca, p. 8

- Pahomi, pp. 90–92, 96, 102. See also Schipor, pp. 220, 222; Vătămanu, p. 315

- Stoicescu, p. 292

- Lecca, pp. 8–9; Schipor, p. 222

- Pahomi, p. 102

- Vătămanu, p. 305

- Pahomi, pp. 101, 102. See also Vătămanu, p. 305

- Vătămanu, p. 305

- Pahomi, p. 102; Schipor, pp. 220, 222

- Lefter, pp. 291, 293, 296, 299–300

- Schipor, p. 220. See also Pahomi, p. 102

- Pahomi, p. 102; Stoicescu, pp. 261–262

- Pahomi, p. 102

- Mihai-Bogdan Atanasiu, "Marital Strategies of the Cantacuzinos", in Revista Istorică, Vol. XXII, Issues 3–4, 2011, p. 401

- Pahomi, p. 87

- Pahomi, pp. 102–103

- Schipor, pp. 220–221, 227

- Pahomi, pp. 85, 87, 99

- Pahomi, pp. 86–87

- Vătămanu, p. 318

- Furtună, p. 169

- Lecca, p. 9

- Ion Felea, "Bătrînul Arbore și crengile sale", in Magazin Istoric, July 1971, p. 8. See also Lecca, pp. 9–10

- Pâslariuc, p. 8

- Pâslariuc, p. 8

- Dragnev, pp. 56–60

- Dragnev, pp. 57–58

- Dragnev, pp. 57–58. See also Lecca, p. 8; Silvestru, p. 12

- Lecca, pp. 7–8

- Maria Frunză, "Costache Stamati", in Alexandru Dima, Ion C. Chițimia, Paul Cornea, Eugen Todoran (eds.), Istoria literaturii române. II: De la Școala Ardeleană la Junimea, p. 374. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 1968

- Chițimia, pp. 686, 692; (in Romanian) Z. Ornea, "Opera literară a lui Hasdeu", in România Literară, Nr. 27/1999

- Chițimia, pp. 686–687

- Chițimia, pp. 686–688

- George Călinescu, "Mihai Eminescu", in Șerban Cioculescu, Ovidiu Papadima, Alexandru Piru (eds.), Istoria literaturii române. III: Epoca marilor clasici, p. 174. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 1973

- Constantin Paraschivescu, "Vasile Cosma. «Un drum de trandafiri cu spini»", in Teatrul Azi, Issues 3–4/2000, pp. 16, 17; Silvestru, pp. 10–11

- Silvestru, pp. 11–12

- Boia, p. 196

- Periodic Report, Second Cycle. Section II - Churches of Moldavia, UNESCO, October 13, 2014

References

- Mihai Adauge, "Invazia tătarilor în vara anului 1518 și lupta de la Ștefănești. Reconstituire", in Studii de Securitate și Apărare, Issue 2/2012, pp. 70–87.

- Cristian Nicolae Apetrei, Reședințele boierești din Țara Românească și Moldova în secolele XIV–XVI. Brăila: Editura Istros, 2009. ISBN 978-973-1871-32-5

- Lucian Boia, History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness. Budapest & New York: Central European University Press, 2001. ISBN 963-9116-96-3

- Cătălina Chelcu, Marius Chelcu, "«...din uricul pe care strămoșii lor l-au avut de la bătrânul Ștefan voievod». Întregiri documentare", in Petronel Zahariuc, Silviu Văcaru (eds.), Ștefan cel Mare la cinci secole de la moartea sa, pp. 108–163. Iași: Editura Alfa, 2003. ISBN 973-8278-27-9

- Ion C. Chițimia, "B. P. Hasdeu", in Alexandru Dima, Ion C. Chițimia, Paul Cornea, Eugen Todoran (eds.), Istoria literaturii române. II: De la Școala Ardeleană la Junimea, pp. 664–705. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 1968.

- Emil Dragnev, "Registrele profeților și apostolilor din tamburul turlei bisericii Sf. Gheorghe din Suceava și contextul artei post-bizantine", in Tyragetia, Vol. IX, Issue 2, 2015, pp. 51–78.

- Valentina Eșanu, "Luca Arbore în misiuni diplomatice ale lui Ștefan cel Mare", in Akademos, Issue 4/201, pp. 136–141.

- Alexandru Furtună, "File din istoria satului Hiliuți, raionul Râșcani", in Enciclopedica. Revistă de Istorie a Științei și Studii Enciclopedice, Issues 1–2/2014, pp. 168–171.

- Ilie Grămadă, "Aspects des relations moldavo-polonaises dans les trois premières décennies du XVI siècle", in Rocznik Lubelski, Vol. 19, 1976, pp. 39–46.

- Octav-George Lecca, Familii de boieri mari și mici din Moldova. Bucharest: Editura Paideia, 2015. ISBN 978-606-748-093-1

- Lucian-Valeriu Lefter, "Obârșia și continuitatea familiei Ponici", in Ovidiu Cristea, Petronel Zahariuc, Gheorghe Lazăr (eds.), Viam inveniam aut faciam. In honorem Ștefan Andreescu, pp. 289–306. Iași: Alexandru Ioan Cuza University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-973-703-779-4

- Mircea Pahomi, "Biserica Arbore — județul Suceava", in Analele Bucovinei, Vol. VIII, Issue 1, 2001, pp. 83–150.

- Virgil Pâslariuc, "Marea boierime moldoveană și raporturile ei cu Bogdan al III-lea (1504–1517)", in Ioan Neculce. Buletinul Muzeului de Istorie a Moldovei, Vol. II–III, 1996–1997, pp. 1–18.

- Liviu Pilat, "'Pretendența' lui Luca Arbore la tronul Moldovei", Analele Putnei, Vol. 9, Issue 2, 2013, pp. 43–50.

- Vasile I. Schipor, "Cronici parohiale din Bucovina (I)", in Analele Bucovinei, Vol. XIV, Issue 1, 2007, pp. 207–251.

- Valentin Silvestru, "Trecutul și prezentul dramei istorice românești", in Teatrul, Issue 8/1966, pp. 4–12.

- N. Stoicescu, Dicționar al marilor dregători din Țara Românească și Moldova. Sec. XIV–XVII. Bucharest: Editura Enciclopedică, 1971. OCLC 822954574

- Adrian Vătămanu, "Logofătul Gavril Trotușan", in Carpica, Vol. X, 1978, pp. 303–322.