Louise Upton Brumback

Louise Upton Brumback (January 17, 1867 – February 22, 1929) was an American artist and art activist known principally for her landscapes and marine scenes. Her paintings won praise from the critics and art collectors of her time.[1][2][3] Writing at the height of her career, a newspaper critic praised her "firmness of character, quick vision, and directness of purpose." She said these traits "proved a solid rock upon which to build up an independent art expression which soon showed to men painters that they had a formidable rival."[4][note 1] As art activist, she supported and led organizations devoted to supporting the work of under-appreciated painters, particularly women.

Louise Upton Brumback | |

|---|---|

| Born | January 17, 1867 |

| Died | February 22, 1929 (aged 62) |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | Landscape painting |

Early life

On finishing high school in the late 1880s, Louise Upton Brumback first looked to a career in music, but soon turned her attention to painting.[4] Her desire to become a professional artist may have been influenced by stories she had heard about her great uncle, William Page, a highly regarded artist who had held the office of president of the National Academy of Design in the early 1870s.[4] She undertook formal study at the age of 33 when she attended William Merritt Chase's school for plein air painting held in the summer months at Shinnecock Hills, Long Island.[4][5][6]

She subsequently studied for a short time at Chase's New York School of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, but principally developed her personal style through close study of the work of other artists both in New York and during travels within the United States.[5][6][7] In 1923 she told an interviewer that she sought formal instruction only to learn good technique, believing that the best art showed the artist's individuality and skill of self-expression. She said painting such art cannot be learned in schools. "The great ones," she said, "won't teach their secrets, and the little ones have none to teach".[4]

In pursuing her career, she obtained the unswerving support of her husband, whose success in the law permitted him to retire at an early age. This support gave her freedom to develop her talent unimpeded by financial need.[4] Her own "firmness of character, quick vision, and directness of purpose" assured that she would apply herself intensely, with courage and originality[note 2] in making paintings that would quickly be recognized for their "clear, forceful rendering, good drawing, and fine color work".[8]

Mature style

Having no need for the money that art sales would provide, Brumback rarely exhibited her paintings in private galleries and never competed for prizes.[4] She preferred group shows to solo ones, and chose for the most part to participate in exhibitions held by clubs, societies, and other institutions of which she was a member, or exhibitions held by museums and other public institutions.[4]

The first show of her professional career was a group exhibition held in 1902 at the Art Club in Kansas City, Missouri, where she and her husband made their home. The two landscapes she contributed displayed her skill in creating atmospheric effects. The subject of the first, a peach orchard, was described as "rich with the hues of blossom time and bathed in a bright spring atmosphere", while the other, a forest scene called The Beeches, was seen to possess "the same luminous atmospheric effects".[8][note 3] In the early years of the twentieth century, she traveled frequently to New York City, and in 1905 she provided a painting called Moonrise to a group exhibition at the National Academy of Design.[9][10] Over the next fifteen years, she would exhibit another ten times at the National Academy.[11]

About 1909 Brumback began spending most cooler months of the year in Manhattan and the warmer months in the seaside resort and artists' colony in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Brumback at first rented studio space in both locations but, while continuing to rent in New York, in 1912 she and her husband bought land and built a house in East Gloucester which they called the "House on the Hill".[4][11][12][13][note 4][note 5] That year, she showed three landscapes at the Twenty-third Annual Exhibition of the New York Watercolor Club.[15] She also contributed a picture, called Little Red Boat, to a group show of contemporary American painting at the Corcoran Gallery. The critic for a local paper called her work "sincere, frank and sympathetic", and said Brumback, although "by no means well known", was "rapidly gaining recognition".[16] The following year, her work appeared in one of her few solo appearances in a New York gallery when she contributed 29 landscapes and marines to a show at the Folsom Galleries.[17][18][note 6]

In 1914, after a decade of few appearances, Brumback began to place her paintings in group, duo, and solo exhibitions. That year, she showed at the National Academy of Design[20] and the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as another Corcoran show;[21] a solo show at the Fine Arts Institute, Kansas City,[22] and a dual-show with M. Bradish Titcomb at the Copley Gallery, Boston, Massachusetts.[23] The trend continued during the next few years, with a solo show at the Petrus Stuyvesant Club, New York,[24] in 1916 and group shows over the next three years: (1) in 1915 at the National Academy of Design,[25] Macbeth Galleries in New York,[26] the Association of Women Painters and Sculptors exhibition at Arlington Galleries in New York,[27] Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts,[28] and the Fine Arts Institute, Kansas City,[14] (2) in 1916 at the Gallery on the Moors, Gloucester,[29] and the Art Institute of Chicago;[30] and (3) in 1917 at the National Academy of Design,[31] the National Arts Club,[32] the Gallery on the Moors,[33] the First Annual Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, Grand Central Palace, New York,[34] and the Chatauqua Institution in the city of that name (New York).[35]

By this time her paintings were becoming famous[35] and she was credited with being one of the best women painters of the time.[36] Her work drew praise for its strong brush work, excellent composition and rich, glowing color,[37] clean palette and vigorous handling,[2] and clear, straightforward presentation of subject.[38] Although two critics said draftsmanship of her work was crude[39] and the "tone" needed refining,[40] most gave her unreserved praise and one, obliquely suggesting why a conservative critic might withhold find fault, said she belonged to "the left wing of New York's feminine talent".[38]

In 1918 and 1919 she embarked on the first of several trips to California where she painted Pacific Coast scenes.[5][11] Writing in July 1919, a critic said of these and earlier paintings that Brumback's work was virile and energetic.[5] In 1921, when the West Coast pictures appeared in a show at Buffalo's Albright Art Gallery, a local critic said they were "characterized by her great versatility and variety of subject matter — still life, the seashore, clouds, snow, forests, mountains—each treated in a different manner" and of one in particular, "a daring essay...there is movement, even excitement, in the canvas, brought out by the opposition of the lines, but chiefly by the opposition of the complementary colors".[41]

With the exception of some floral arrangements, Brumback did not paint interiors or urban scenes. Working out of doors in rural settings, she sought to capture the subjective feeling of a scene, its "mood of nature," as she put it, however much time and effort it might take to achieve that goal.[42][43] While praising the "strong, clean palette and vigorous handling" in her landscapes and marines, one critic noted that her success derived from knowing what to leave out of a picture as well as what to put in it.[note 7]

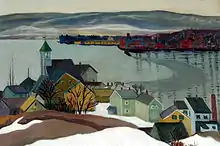

In 1927, when Brumback turned 60, her skill and her appetite for hard work remained undiminished.[note 8] The art reporter for the New York Evening Post praised a solo exhibition of that year for the subtlety and rhythm of the flower paintings and landscapes in oil and watercolor that it contained,[44] and the reporter for the Times drew attention to the painting Gloucester in Winter in this show for its success in evoking a mood: the charm of a coastal resort that "flees with the opening of the Summer hotels".[45]

Art activist

As an artist, Brumback was viewed as energetic, forceful, virile, and direct.[4][note 9] Deploying these character traits as an activist, she became a strong advocate for artists and of democratic principles within the art world.[4] In 1922 she became president of a new society of artists—The Gloucester Society of Artists—devoted to exhibiting work without prior selection by juries. She believed that juries unfairly prevented good art from being seen, particularly art made by women, and, that, by skewing public taste, they inhibited young artists from developing their creative potential.[4][39][46][note 10] That year she also opened a gallery in her New York apartment both to show her own work, on occasion, and to show the work of other artists who she believed deserved greater exposure.[9][48] In 1925 she became a founding member of the New York Society of Women Artists[49] and participated in its annual shows up to the time of her death.[50] Like the Gloucester society, this one believed in exhibiting with no jury. It also decided that each member should get same amount of space to display her work and that the membership would be limited to 30 painters and sculptors.[51]

Exhibitions

Brumback exhibited her work in private galleries, shows of the societies of which she was a member, and public institutions such as the National Academy of Design, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Pennsylvania Academy, Albright Gallery, Art Institute of Chicago, Newark Museum, and the Museum of the Omaha Society of Fine Arts, Omaha, Nebraska.[4][43][52] She also showed at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition of San Francisco in 1915.

She participated in a large number of group and solo exhibitions. Solo exhibitions included shows at the Folson Gallery (1913, New York), Fine Arts Institute (1914, Kansas City, Mo.), Petrus Stuyvesant Club (1916, New York), Albright Art Gallery (1920, Buffalo, N.Y.), Woman's City Club (1922, Kansas City, Mo.), Art Institute of Chicago (1921), Memorial Art Gallery (1921, Rochester, N.Y.), Knoedler Galleries (1921, New York), Mrs. Sterner's Gallery (1922, New York), Painters and Sculptors Gallery (1926, New York), Marie Sterner's Art Patrons of America (1927, New York). Her participation in group shows included repeated appearances with the Art Institute of Chicago, Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, Corcoran Gallery (Washington, D.C.), Gallery on the Moors (Gloucester, Mass.), Gloucester Society of Artists, MacDowell Club Galleries, National Academy of Design, National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, New York Society of Women Artists, Pen and Brush Club, and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (Philadelphia, Penn.).[note 11]

Memberships

Brumback belonged to the American Federation of Arts, Art Association of Gloucester, Memorial Art Gallery (Rochester, New York), National Arts Club, National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, New York Society of Women Artists, Pen and Brush Club, Salons of America, and Society of Independent Artists.[note 12]

Personal life

Brumback became a painter after her marriage in 1891 and consistently used Louise Upton Brumback as her professional name. Her married name, Mrs. Frank Brumback, appeared only in newspapers' society notices. Various truncations and misspellings of her name appeared from time to time. The most common was the rendering her last name as "Brumbach" as in "Louise Upton Brumbach"[14][20][23][36][55] or, on one case, "L.M. Brumbach."[56]

She was born in Rochester, New York, on January 17.[6][53][57] There is disagreement about the year of her birth. Although references published since 1900 give 1872, sources from earlier years give 1867. Census reports for 1870, 1875, and 1880 give her birth year as 1867; her gravestone gives that year; and a genealogy published in 1900 gives it as well.[58][59][60][61][62] The earliest source giving a later birth date is the United States Census of 1900 which lists her age as 29 with presumptive birth year of 1871 or 1872.[63]

Parents

Brumback's parents were Charles E. Upton and Louise Rackett Upton. They were sufficiently prominent that the large house in which they lived stood on the corner of a street, Upton Park, named after them.[4][43][64][note 13] Brumback's siblings included an older sister, Annie Upton (born 1860), a brother, George Rackett Upton (born 1863), and a twin sister, Alice. Following the death of George in 1866, her parents adopted a cousin, Charles F. Gorrard (also known as Charles Torrance) born 1859), as their son.[58][59][66][67]

Her father was a banker and speculator in commodities and stocks. In December 1882 he embezzled large sums from a bank he owned in an effort to cover a huge loss he had incurred in a speculation on the price of oil.[68][69][70] The bank failed when it became known that Upton would be unable to repay the money he had taken.[71] Convicted of embezzlement in 1883, he died in 1886 while an appeal was pending.[72] Brumback's mother was Louise Rackett Upton,[73][74] author of a novel, Castles in the Air (New York, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1879).[75]

Education

At an early age Louise and her twin sister Alice were sent to Mrs. Sylvanus Reed's School, a boarding school in New York City which had a curriculum of sufficient rigor that graduates could pass the examinations for entrance to Columbia College.[note 14] Established in 1864 the school was run by Caroline Gallup Reed, widow of the Rev. Sylvanus Reed.[76] Upon leaving it, Brumback enrolled in one of New York's conservatories of music.[note 15]

Move to Kansas City and marriage

In 1889 Louise Rackett Upton Brumback and her two daughters moved from New York to Kansas City[5] and on June 11, 1891, Brumback married Frank Fullerton Brumback, a prominent attorney in Kansas City, Missouri, and son of the prominent Kansas Citian judge Jefferson Brumback.[note 16] The couple had one child, Jefferson Upton Brumback. He was killed in flight while serving as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Air Service.[83] In 1921 Brumback donated a painting called Fair and Cooler to the Memorial Art Gallery in Rochester in memory of her son.[54]

Brumback and her husband participated in the well-heeled society of Kansas City at the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. She sponsored parties, such as one held in 1896 at Kansas City's Lyceum Hall, participated in musical entertainments, such as one written by her sister Alice that same year, and herself wrote an operetta that was performed at a local club the following year.[84][85] In early 1900’s Brumback and her husband and son lived in a mansion on 4019 Warwick boulevard in Kansas City.[86] In 1909 Brumback and her husband built a larger house, designed by Louis Curtiss,[87][note 17] and she drew murals in its rooms showing scenes of Gloucester much like her easel paintings.[5][note 18] Soon after the house was completed, Frank Brumback retired from legal practice and, as already noted, thereafter gave full support to Brumback's professional career.[9] In 1920 they leased the house for an indefinite period and spent all their time in Gloucester, Manhattan, and in travel.[88]

Brumback died at the age of 62 in Gloucester, Massachusetts, on February 22, 1929.[6][53][57]

Notes

- Here is the full quote: "Her art goes steadily ahead subject to the seriousness of her thought and her profound respect for nature. Her work is direct, free and forceful, as representing an independent thinker and an impressive personality. She understands the harmonies of color, balance, rhythm and composition, yet it is not these technical principles that are mainly manifest in her work, but a sterling quality of deep sincerity, natural talents cultivated by close application and keen observation as well as feeling and sentiment."[4]

- "Her work is direct, free and forceful, as representing an independent thinker and an impressive personality".[4]

- "Mrs. Louise Upton Brumback exhibited two landscapes so utterly unlike in theme and execution as to be a fair test of her versatility. One depicted a peach orchard, rich with the hues of blossom time and bathed in a bright spring atmosphere. The other, entitled 'The Beeches,' was a forest scene, with giant trees in the immediate foreground and other tree masses in the distance, this canvas being characterized by the same luminous atmospheric effects as the other. In point of clear, forceful rendering, good drawing, and fine color work, these two pictures were second to none in the exhibition. Mrs. Brumback [has] a rare ability to obtain luminous atmospheric effects".[8]

- "They were summer residents of East Gloucester, Massachusetts where in 1912, they acquired about 10 acres of land on Sunset Hill near Rocky Pasture Road".[12]

- The American Art Annual for 1915 listed Brumback's three addresses: Permanent: 500 East 36th St. Kansas City, Missouri; Summer: The House on the Hill, Gloucester, Massachusetts; Also: 140 West 57th St, New York.[14]

- In reviewing this show the art critic for the New York Herald wrote that "Mrs. Brumback is a Kansas City woman, but she has a summer home at Gloucester, Mass., and the pictures in the present exhibition nearly all were painted there last summer. She is most successful in pictures in which water appears as a theme. The best isGloucester, a hazy view of the city from across the bay, with a splendid rendition of distance. Across the Sand is another work of rare quality, conveying the feeling of the beach",[17] and the critic for the New York Press said "those who admire courage will find much to please them in her exhibition".[19]

- "The sea and its harbors, fruit trees in bloom, gardens filled with flowing shrubs, bouquets in jugs, [are] all subjects asking for a strong, clean palette and vigorous handling. Mrs. Brummback sees her handsome world with a direct vision and no nonsense in her mind. She works for those things that may be grasped by a clear intelligence, and where sentiment is introduced it is the sentiment of the morning on a day washed by early rain. No mists, no fogs, no blinding midday sun, nothing to interfere with clarity. It is very little wonder that her work appeals to the American public.[2]

- Regarding her capacity for hard work, a critic had noted in 1919 that "She attributes her success as an artist to her application of the three rules of golf: first keep your eye on the ball; second, keep your eye on the ball; third, keep your eye on the ball. With her it is hard work, hard work, and more hard work—not unintelligent pegging away, but thoughtful research".[5]

- This is one example of many critical notices that attribute these characteristics to her: "Following her natural bent for directness and breadth, she put her subjects on canvas in that forceful, convincing manner that is so integrally a part of herself. She has strong opinion about all art matters, studies carefully every form of expression and rules and makes her decisions as to what is best for the ultimate advancement of art in general."[4]

- Describing the new society a reporter said "the liberals, or 'liberal-minded conservatives' as they prefer to be called, organized the Gloucester Society of Artists, electing Louise Upton Brumback president.[47] The Society was formed after a "group of artists met at Grace Horne’s more avant-garde gallery... Brumback was elected president, and the art committee included Stuart Davis and Alice Beach Winter.[11] It provided a "large gallery, restaurant, bathing beach, tennis, croquet, all available to members."[9] At the same time another art group was formed in Gloucester, the North Shore Arts Association, having similar ideals but taking a somewhat more conservative approach. Brumback became a member of that organization as well.[47]

- This brief summary of Brumback's appearances in solo and group shows comes from notices in contemporary newspapers, art magazines, and published catalogs. Where a city is not named it is either obvious from context or is New York.

- This representative list of memberships comes from the American Art Annual,[53] Buffalo Courier,[36] Rochester Democrat,[43] Clifton Springs Press,[54] and an art reference web site.[12] If a city is not named, the location is New York.

- Listed in the Historic American Buildings Survey, the house is located at 666 East Avenue, at the northeast corner of East Avenue and Upton Park. It was constructed between 1852 and 1854 for Mr. and Mrs. Charles Perkins Bissell. Charles E. Upton bought it April 1, 1867, shortly after Brumback's birth and sold it 20 years later to help pay his debts.[65]

- Although women could not become students in Columbia College until 1983, the preparation they received at Mrs. Sylvanus Reed's School gave them a firm grounding in modern and ancient languages, fine arts, geography, biology, and mathematics, including trigonometry and calculus.[76]

- When Brumback was young, New York City had several conservatories of music. The one she attended may have been Ernest G. Eberhard's Grand Conservatory of Music at 46 West 23rd Street in New York, a prominent co-educational school of the time which taught drawing and painting as well as music and the dramatic arts.[77]

- Frank Brumback wrote a legal treatise, a Christmas story, and a popular song. The treatise is "Today and Yesterday," American Law Review (vol. 50, March 1916, pp. 248–61).[78] The story is "The Deserted Kingdom, a Christmas Ghost Story", Outing: Sport, Adventure, Travel, Fiction (Vol. 21, No. 4, January 1893, pp. 282–86).[79][80][81][82]

- Located at 500 E. 36th Street in Kansas City, this colonial revival style house still remained in 2007.[87]

- Brumback's murals were described in an article that appeared in 1919: "The charms of this New England resort have been transferred to the walls of the artist's Kansas City home in a nice bit of mural decoration. Instead of re-papering a room, this clever little artist dashed her paint pots on its walls, sketching on one, the view from the east window of her Gloucester cottage at sunrise; on another she did the harbor with its picturesque boats and the fishermen; and on the west, over the mantle, she has a charming beach scene with its bathers, pink umbrellas, and yellow sand. The last view is of the village on a misty moonlight night."[5]

References

- "At Knoedler's". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1921-02-27. p. 6.

- "The World of Art". The New York Times. 1922-04-16. p. 57.

- L.K. (1927-03-13). "Art Patrons of America Galleries". The New York Times. p. X10.

- Lula Merrick (1923-09-02). "In the World of Art". Morning Telegraph. New York. p. 7.

- Seachrest, Effie (July 1919). "Louise Upton Brumback". American Magazine of Art. New York: American Federation of Arts. 10 (9): 336–337. JSTOR 23925588.

- "Brumback, Louise". World Art Purveyors LLC. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- John E.D. Trask, ed. (1915). Catalogue de luxe of the Department of Fine Arts, Panama-Pacific International Exposition. P. Elder and Company, San Francisco. p. 294.

- Reed, Elizabeth E. (January 1902). "Art Exhibition at Kansas City". Brush and Pencil. Chicago: Brush and Pencil Publishing Company. 9 (4): 201–205. doi:10.2307/25505702. JSTOR 25505702.

- Lula Merrick (1922-12-31). "In the World of Art". Morning Telegraph. New York. p. 3.

- "Figure Pictures and Portraits at the Academy". The New York Times. 1905-01-22. p. X1.

- "Vose Galleries – Louise Upton Brumback". Retrieved 2015-07-11.

- "Louise Brumback". askArt. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- "Art and Artists". American Art News. New York. 15 (5): 7. November 11, 1916. JSTOR 25588956.

- "American Art Annual". 12. Washington, D.C.: American Federation of Arts. 1915: 131.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Twenty-Third Annual Exhibition (Catalogue). New York: New York Water Color Club. 1912. p. 13.

- "News and Notes of Art and Artists". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. 1912-12-28. p. 4.

Mrs. Brumback is by no means well known, but, she is rapidly gaining recognition.

- "Two Western Women Show Fine Landscapes". New York Herald. 1913-12-18. p. 11.

- "Mrs. Brumback's Pictures at the Folsom Galleries". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1913-12-20. p. 7.

- "Notes and Comment". New York Press. 1913-12-21. p. 4.

- "Exhibitions Now On; The Spring Academy". American Art News. New York. 12 (25): 6. March 28, 1914. JSTOR 25591182.

- American Oil Paintings and Sculpture; The Twenty-Seventh Annual Exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago (PDF). Art Institute of Chicago. 1914.

- Florence Nightingale Levy (1914). American Art Directory. R.R. Bowker. p. 182.

- "Current Notes". Arts and Decoration. New York: Adam Bunge. 5: 72. December 1914. Retrieved 2015-07-13.

- "Louise Upton Brumback at Petrus Stuyvesant Club". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1916-04-02. p. E5.

- "Academy of Design in Winter Show". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1915-12-18. p. 8.

- William B.McCormick (1915-01-10). "First 1915 Macbeth Show Makes Old Friends and New Seem Equally Welcome". New York Press. p. 11.

- "135 Women Offer Art For "Christmas Money"". New York Herald. 1915-01-10. p. 12.

- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1915). Catalogue of the 110th Annual Exhibition. Philadelphia, Pa.: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. p. 51.

- "News and Comment in the World of Art". New York Sun. 1916-09-03. p. 3.

- Catalogue of the Twenty-Ninth Annual American Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture; The Art Institute of Chicago. Art Institute of Chicago. 1916. p. 296.

- "National Academy of Design: Second Notice; Art at Home and Abroad". The New York Times. 1917-03-25. p. SM7.

- "Exhibitions Now On". American Art News. New York. 15 (13): 2. January 6, 1917. JSTOR 25588990.

- "Gallery on the Moors Filled by Cape Ann Artists". Christian Science Monitor. Boston. 1917-07-27. p. 7.

- Catalogue of the First Annual Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists. The Society of Independent Artists, Printed by William Edwin Rudge, New York. 1917.

- "Great Interest in Art Exhibit". Jamestown Evening Journal. 1916-05-25. p. 3.

- "Albright Gallery Opens New Exhibit". Buffalo Courier. 1921-09-11. p. 57.

- "A Good MacDowell Show". American Art News. New York. 16 (26): 2. April 6, 1918. JSTOR 25589267.

- "Women's Group a Notable Showing at Art Center". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1930-04-06. p. E5.

- "More Gloucester Artists". Christian Science Monitor. Boston. 1923-07-28. p. 7.

- "Women Artists; a National Association and a Visitor". New York Tribune. 1921-02-27. p. 7.

- "Albright Gallery Opens New Exhibit". Buffalo Evening News. Buffalo, New York. 1921-09-24. p. 22.

- "News and Notes". The New York Times. 1913-12-21. p. 15.

- "Artist of Note Exhibiting Here". Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. 1921-05-15. p. 15.

- "Notes and Comment on Art". New Evening Post. 1927-03-12. p. 13.

- E.L.C. (1927-03-13). "Paintings, Sculpture and Prints by the New York Society of Women Artists". The New York Times. p. X11.

- "Works by William Meyerowitz, from the Collection of the Cape Ann Museum". Cape Ann Museum. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- "Louise Upton Brumback's Paintings". American Art News. New York. 21 (1): 2. October 14, 1922. JSTOR 25590008.

- "Mrs. Brumback's New Gallery". American Art News. New York. 21 (11): 2. December 23, 1922. JSTOR 25590044.

- "Women Artists Form New Group". The New York Times. 1925-05-03. p. X11.

- Helen Appleton Read (1926-04-25). "Women's Art Not Necessarily Feminine, New Group Demonstrates". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 7.

- "About Artists And Their Work". New York Evening Post. 1926-03-13. p. 9.

- "More Gloucester Artists". The New York Times. 1923-07-29. p. 8.

- American Art Annual. MacMillan Company. 1927. p. 383.

- "Western New York News Items". Clifton Springs Press. Clifton Springs, New York. 1921-05-19. p. 1.

- The International Studio. John Lane Company. 1917. p. 82.

- Ronald G. Pisano; William Merritt Chase; D. Frederick Baker; Marjorie Shelley (2007). William Merritt Chase: Portraits in oil. Yale University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-300-11021-0.

- Who's who in American Art. R. R. Bowker. 1935. p. 625.

- James Boughton; Willis A. Boughton (1890). Bouton—Boughton Family: Descendants of John Boution, a Native of France, who Embarked from Gravesend, Eng., and Landed at Boston in December, 1635, and Settled at Norwalk, Ct. J. Munsell's Sons. p. 317.

Charles E. Upton (son of Samuel and Olive Boughton Upton) was born in Victor, N. Y., July 4, 1833. He settled in Rochester, N. Y., where he died March 20, 1886. He was a man of the purest character and of unusual ability. Thoroughly unselfish, and finding his highest pleasure in assisting others, especially young men, in the battle of life, he was beloved by his fellow citizens as men rarely are. His widow and daughters reside in New York city. Married Louise Racket, Oct. 12, 1859. Children of Charles E. and Louise Racket Upton, of Rochester, N. Y.: -Anne Upton, b. June 25, 18G0. -George Racket Upton, b. March 26, 1863, d. April 6, 1866. -Louise Upton and Alice Upton, twins b. Jan. 17, 1867 -Charles E. Upton adopted his nephew Charles Torrance.

- "Person Details for Louisa Upton in household of Charles Upton, "United States Census, 1870"". "United States Census, 1870," FamilySearch; citing p. 58, family 424, NARA microfilm publication M593 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 552,471. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- "Louise Upton in household of Charles E Upton, Rochester, Monroe, New York, United States". "New York, State Census, 1875"; citing p. 15, line 2, State Library, Albany; FHL microfilm 833,780. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- "Louise Upton in household of Chars E Upton, Rochester, Monroe, New York, United States". "United States Census, 1880," database with images, FamilySearch; citing enumeration district 112, sheet 418A, NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 0864; FHL microfilm 1,254,864. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- "Louise Upton Brumback (1867–1929) – Find A Grave Memorial". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2015-07-06.

- "Louise A Brumback in household of Frank Brumback, Precinct 6 Kansas City Ward 11, Jackson, Missouri, United States". "United States Census, 1900," index and images, FamilySearch; citing sheet 4A, family 67, NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,240,864. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- "Bissell House (East Avenue Historic District) – Rochester, NY". - NRHP Historic Districts - Contributing Buildings on Waymarking.com. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- "Charles Bissell House; HABS No. NY-5640" (PDF). Historic American Buildings Survey. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- "Louise Upton in household of Charles Upton, Rochester, Monroe, New York, United States". FamilySearch, citing p. 58, family 424, NARA microfilm publication M593 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 552,471. Retrieved 2015-04-22.

- "Death of Charles Upton". Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. 1886-03-21.

- "A Weak Bank Wrecked: Failure of the City Bank of Rochester". The New York Times. 1882-12-21. p. 1.

- "Panic in the Oil Market". The New York Times. 1882-12-20. p. 1.

- "Editorial: Charles E. Upton". The New York Times. 1882-12-21. p. 4.

- William Farley Peck (1884). Semi-centennial History of the City of Rochester: With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. D. Mason & Company. p. 465.

- "Editorial Comment". Pittsburgh Daily Post. 1883-07-27. p. 2.

The conviction of Charles E. Upton, late president of the City Bank of Rochester, on a charge of embezzling the funds of that institution in order to retrieve his disastrous gambling in oil, is received by the press of that city in an excellent spirit, as a vindication of public justice which not only does not exclude warm personal sympathy for the criminal and his family, but is made more signal by that sympathy. No doubt this feeling of the community was that of the jury which convicted Upton. The verdict, it is owned, was a surprise, as it was expected that the social position and the personal popularity of the defendant would pervert justice through sympathy. It is so rare as to be noteworthy when an American jury in a criminal case can put aside the human feelings of its own members as irrelevant to the case it has to try.

- "Birth of Louise Rackett". "New York, Births and Christenings, 1640–1962," FamilySearch, Charles Rackett in entry for Louise Rackett, 23 Apr 1839; FHL microfilm Q974.71 K28N. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- Horace Greeley; Park Benjamin (1838). The New-Yorker. H. Greeley & Company. p. 239.

- Louise R. Upton (1879). Castles in the Air. G.P. Putnam.

- "Classified Ad: Mrs. Sylvanus Reed's English, French, and German Boarding and Day School". The New York Times. 1874-09-25. p. 6.

Mrs. Sylvanus Reed's English, French, and German Boarding and Day School for young ladies and little girls, Nos. 6 and 8 East 53rd st., New York. Exercises for next year will begin at 9 A.M., Oct. 1, when all pupils should be present. New scholars will report Sept. 29, when teachers will class them.

- "Classified Ad: Grand Conservatory of Music". The New York Times. 1886-09-18. p. 6.

- United States Law Review. Little, Brown. 1916. pp. 248–261.

- Outing: Sport, Adventure, Travel, Fiction. W. B. Holland. 1893. pp. 282–86.

- Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature. H. W. Wilson Company. 1920. p. 94.

- The Deserted Kingdom, a Christmas Ghost Story by Frank F. Brumback, in Outing: Sport, Adventure, Travel, Fiction, January, 1893. W. B. Holland. 1893. pp. 282–286.

- Library of Congress. Copyright Office (1917). Musical Compositions: Part 3. Library of Congress. p. 943.

Song of the Freemen; words by F.F. Brumback, music by Roger W.D. Beecher. Copyright July 28, 1917; Frank F. Brumback, Kansas City, Mo.

- "New York Flyer Killed In Fight With Five Huns". New York Herald. 1918-12-04. p. 4.

Jefferson Upton Brumback, lieutenant, Air Service, killed last Monday afternoon in an airplane accident at the Wright Flying Field, Dayton, Ohio, was the nephew of Benjamin H. Baker, of No. 59 East Seventy-third street. Lieutenant Brumback, who was well known in New York, was the son of Mr. and Mrs. Frank F. Brumback, of Kansas City.

- "Home Department". Kansas City Journal. 1896-12-06. p. 9.

- "Home Department". Kansas City Journal. 1897-02-28. p. 15.

- "The Journal 17 Apr 1948, page 1". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- "Louis Curtiss Buildings". Architects: KCRag Forum. Retrieved 2015-07-09.

- "Artists Notes". American Art News. New York. 18 (21): 9. March 13, 1920. JSTOR 255895984.

Mrs. Louise Upton Brumback, who has been in Kansas City for two years past, is returning to N.Y. having leased her house in the Missouri city for an indefinite period, and with Mr. Brumback, after some months stay here, will spend the summer at their summer home at East Gloucester, Mass.