Louis P. Lochner

Ludwig "Louis" Paul Lochner (February 22, 1887 – January 8, 1975) was an American political activist, journalist, and author. During World War I, Lochner was a leading figure in the American and the international anti-war movement. Later, he served for many years as head of the Berlin bureau of Associated Press and was best remembered for his work there as a foreign correspondent. Lochner was awarded the 1939 Pulitzer Prize for correspondence for his wartime reporting from Nazi Germany. In December 1941, Lochner was interned by the Nazis but was later released in a prisoner exchange.

Early life

Louis Lochner was born February 22, 1887, in Springfield, Illinois, to Johann Friedrich Karl Lochner and Maria Lochner née von Haugwitz. The senior Lochner was a Lutheran minister.[1]

In 1905, Louis graduated from the Wisconsin Music Conservatory.[1] He went on to attend the University of Wisconsin at Madison, from which he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in earning a bachelor's degree in 1909.[1]

On September 7, 1910, he married Emmy Hoyer; they had two children: Elsbeth and Robert. Hoyer died in 1920.

Lochner married again in 1922, his second wife being Hilde De Terra, née Steinberger, who brought Rosemarie De Terra, her daughter from her first marriage, into the family.

Political activism

During the second decade of the 20th century, Lochner was a leading activist in the American pacifist movement. In late 1914, he was appointed Executive Director of the Chicago-based Emergency Peace Federation and worked closely with social activist Jane Addams in an attempt to call an international conference of neutral nations to mediate an end to World War I.[2] Lochner, Addams, and their Emergency Peace Federation were instrumental in convening a national conference in Chicago in February 1915 that brought together delegates representing pacifist, religious, and anti-militarist political organizations from around the United States.[3]

Lochner became a secretary to Henry Ford in 1915. He served as the head of publicity for Ford's ill-fated Peace Ship and he was the general secretary of the Ford-funded Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation.[1]

Journalist

After the end of the war in 1918, Lochner moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to join the staff of the Milwaukee Free Press.[1] He also edited for the International Labor News Service, a press agency of the day.[1]

In 1924, Lochner was appointed to the Berlin bureau of Associated Press.[1] He remained there until 1946 and twice interviewed Adolf Hitler, first in 1930 and then in 1933.[1]

When the German invasion of Poland in 1939 led to World War II, Lochner became the first foreign journalist to follow the German Army into battle. His bravery in remaining in Nazi Germany, despite the outbreak of hostilities, to provide objective and measured news coverage was rewarded with the 1939 Pulitzer Prize for correspondence.[1]

He reported further on the German side of the war by accompanying the German Army on the Western Front in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France and witnessing the 1940 French armistice in Compiègne.

After the December 1941 declaration of war between Germany and the United States, the German government interned Americans remaining in the Third Reich. Lochner was held for nearly five months at Bad Nauheim near Frankfurt am Main before he was released in May 1942 as part of a prisoner exchange for interned German diplomats and correspondents.

Upon his release, Lochner took eight months' leave of absence for an extended lecture tour throughout North America, which he spent publicly attacking Nazism and warning of its dangers.[1] In that interval he wrote a book warning of the fascist menace, What About Germany?[1]

From 1942 to 1944 Lochner worked as a news analyst and radio commentator for the National Broadcasting Company.[1] Then, he departed once again for Europe and as a war correspondent until after the war ended.[1]

Post-war

In 1948 Lochner translated and edited a volume of diary material by the Nazi propaganda chief, Joseph Goebbels, which attained considerable commercial success. That set him on a new path as a writer of non-fiction books. In the 1950s, Lochner published a further three volumes on various aspects of German history and current affairs.

Lochner also returned to his Lutheran roots as a member of the editorial board of The Lutheran Witness and a columnist for The Lutheran Layman and The Lutheran Witness Reporter.

In 1955, Lochner published his memoirs, Stets das Unerwartete: Erinnerungen aus Deutschland 1921–1953 (Always the Unexpected: Recollections of Germany 1921–1953). An English-language edition was published in 1956.

Lochner spent his later years compiling a series of articles for the quarterly journal of the Wisconsin Historical Society, which was published on the campus of his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin.

Death and legacy

Lochner died on January 8, 1975,[4] in Wiesbaden, West Germany.

In 2005, a posthumous volume of Lochner's German journalism was published as Journalist at the Brink: Louis P. Lochner in Berlin, 1922–1942 and was edited by Morrell Heald.

Lochner's papers are held at the Concordia Historical Institute in St. Louis, Missouri. An online finding aid is available.[5] Many of the volumes from his personal library found their way to Valparaiso University in Indiana, an institution at which Lochner had lectured at various times during his career.[6]

The archive of the Henry Ford Peace Expedition of 1915–1916, including scattered material by Lochner, is at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania as part of its Peace Collection.[7]

The papers of Lochner's son Robert, which include photographs of and correspondence by Louis Lochner, are at the Hoover Institution archives at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California.[8]

Works

Books and pamphlets

- 'The Cosmopolitan Club Movement', in Gustav Spiller, ed., Papers on Inter-Racial Problems Communicated to the First Universal Races Congress, London: P. S. King, 1911, p. 439ff.

- Reprinted as The Cosmopolitan Club Movement, New York: American Association for International Conciliation, 1912.

- Internationalism Among Universities. Boston: World Peace Foundation, 1913.

- Personal Observations on the Outbreak of the War. Chicago: Chicago Peace Society, 1914.

- Pacifism and the Great War. Chicago: Chicago Peace Society, 1914.

- Wanted: Aggressive Pacifism. Chicago: Chicago Peace Society, 1915.

- The Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation. Stockholm: Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation, 1916.

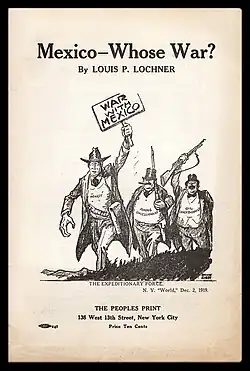

- Mexico — Whose War? New York: The Peoples Print, n.d. [c. 1919].

- Die Staatsmännischen Experimente des Autokönigs Henry Ford (The Experiment in Statesmanship of Auto King Henry Ford). Munich: Verlag für Kulturpolitik, 1923.—Reissued as America's Don Quixote: Henry Ford's Attempt to Save Europe. (London, 1924) and Henry Ford: America's Don Quixote. (New York, 1925).

- What About Germany? New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1942.

- What About Poland? A Radio Broadcast over National Broadcasting Co. Beverly Hills, CA: Friends of Poland, 1944.

- Fritz Kreisler. New York: Macmillan, 1951.

- Tycoons and Tyrant: German Industry from Hitler to Adenauer. Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1954.

- Stets das Unerwartete: Erinnerungen aus Deutschland 1921–1953 (Always the Unexpected: Recollections of Germany, 1921–1953). Darmstadt: Franz Schneekluth Verlag, 1955.

- Always the Unexpected: A Book of Reminiscences. New York: Macmillan, 1956.

- Herbert Hoover and Germany. New York: Macmillan, 1960.

Edited or translated

- Margaret Leng, The Wood-Peasant's Grandchild. Germany: Johannes Herrmann, n.d. [c. 1920s].

- Rosa Luxemburg, Letters to Karl and Luise Kautsky from 1896 to 1918. New York, R.M. McBride and Co., 1925.

- Joseph Goebbels, The Goebbels Diaries, 1942–1943. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1948.

Selected articles

- "Our Man in Berlin: As an American journalist in Germany, Louis Lochner told the story of the rise and fall of the Third Reich," by Meg Jones, On Wisconsin Magazine, (Summer 2017.)

- "Communications and the Mass-Produced Mind," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 41, no. 4 (Summer 1958), pp. 244–251.

- "Aboard the Airship Hindenburg: Louis P. Lochner's Diary of Its Maiden Flight to the United States," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 49, no. 2 (Winter 1965/66), pp. 101–121.

- "Round Robins from Berlin: Louis P. Lochner's Letters to His Children, 1932–1941," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 50, no. 4 (Summer 1967), pp. 291–336.

- "The Blitzkrieg in Belgium: A Newsman's Eyewitness Account," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 50, no. 4 (Summer 1967), pp. 337–346.

Footnotes

- "Louis Lochner 1887 - 1975". Traces. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014.

- Archibald Stevenson, ed., Revolutionary Radicalism: Its History, Purpose and Tactics with an Exposition and Discussion of the Steps Being Taken and Required to Curb It, Being the Report of the Joint Legislative Committee Investigating Seditious Activities, Filed April 24, 1920, in the Senate of the State of New York: Part 1: Revolutionary and Subversive Movements Abroad and at Home, Volume 1. Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Co., 1920; pp. 971-972. Hereafter: Lusk Report.

- Stevenson (ed.), Lusk Report, vol. 1, pg. 974.

- Brennan, Elizabeth A.; Clarage, Elizabeth C. (1999). Who's who of Pulitzer Prize Winners. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-57356-111-2.

- "Louis P. Lochner (1887-1975) Family Collection, 1524-1975". Concordia Historical Institute. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010.

- "Louis P. Lochner Collection". Valparaiso University. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011.

- "Henry Ford Peace Expedition Records (DG 018), Swarthmore College Peace Collection". Swarthmore College. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- "Lochner (Robert H.) papers". Online Archive of California. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

Further reading

- Barbara S. Kraft, The Peace Ship: Henry Ford's Pacifist Adventure in the First World War. New York: Macmillan, 1978.

- Meg Jones, "World War II Milwaukee." The History Press, 2015

External links

- "Louis Lochner, 1887-1975," Traces website, www.traces.org/ —Includes excellent account of Lochner's interment.