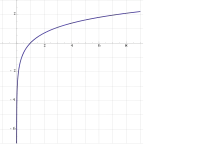

Logarithmic growth

In mathematics, logarithmic growth describes a phenomenon whose size or cost can be described as a logarithm function of some input. e.g. y = C log (x). Any logarithm base can be used, since one can be converted to another by multiplying by a fixed constant.[1] Logarithmic growth is the inverse of exponential growth and is very slow.[2]

A familiar example of logarithmic growth is a number, N, in positional notation, which grows as logb (N), where b is the base of the number system used, e.g. 10 for decimal arithmetic.[3] In more advanced mathematics, the partial sums of the harmonic series

grow logarithmically.[4] In the design of computer algorithms, logarithmic growth, and related variants, such as log-linear, or linearithmic, growth are very desirable indications of efficiency, and occur in the time complexity analysis of algorithms such as binary search.[1]

Logarithmic growth can lead to apparent paradoxes, as in the martingale roulette system, where the potential winnings before bankruptcy grow as the logarithm of the gambler's bankroll.[5] It also plays a role in the St. Petersburg paradox.[6]

In microbiology, the rapidly growing exponential growth phase of a cell culture is sometimes called logarithmic growth. During this bacterial growth phase, the number of new cells appearing is proportional to the population. This terminological confusion between logarithmic growth and exponential growth may be explained by the fact that exponential growth curves may be straightened by plotting them using a logarithmic scale for the growth axis.[7]

See also

- Iterated logarithm – Inverse function to a tower of powers (an even slower growth model)

References

- Litvin, G. (2009), Programming With C++ And Data Structures, 1E, Vikas Publishing House Pvt Ltd, pp. AAL-9–AAL-10, ISBN 9788125915454.

- Szecsei, Denise (2006), Calculus, Career Press, pp. 57–58, ISBN 9781564149145.

- Salomon, David; Motta, G.; Bryant, D. (2007), Data Compression: The Complete Reference, Springer, p. 49, ISBN 9781846286032.

- Clawson, Calvin C. (1999), Mathematical Mysteries: The Beauty and Magic of Numbers, Da Capo Press, p. 112, ISBN 9780738202594.

- Tijms, Henk (2012), Understanding Probability, Cambridge University Press, p. 94, ISBN 9781107658561.

- Friedman, Craig; Sandow, Sven (2010), Utility-Based Learning from Data, CRC Press, p. 97, ISBN 9781420011289.

- Barbeau, Edward J. (2013), More Fallacies, Flaws & Flimflam, Mathematical Association of America, p. 52, ISBN 9780883855805.