Local government financing vehicle

A local government financing vehicle (LGFV) (Chinese: 地方政府融资平台), also known as a local financing platform (LFP), is a funding mechanism by a local government in China. It usually exists in the form of an investment company that borrows money to finance real estate development and other local infrastructure projects.[1] LGFVs can borrow money from banks, or they can borrow from individuals by selling bonds known as "municipal investment bonds" or "municipal corporate bonds" (城市投资债券 or 城投债), which are repackaged as "wealth management products" and sold to individuals.[2]

Since local governments in China are not allowed to issue municipal bonds,[3]: 86 LGFVs have played a unique role in securing funding for local governments to develop their economies. However, the vehicles rarely make enough returns to pay back their debts, often requiring local governments to raise more money to pay back their creditors.

Both the number and the indebtedness of LGFVs have soared in recent years, sparking fears about their inability to repay debts as well as subsequent defaults.[4] Although LGFVs are operated by local governments, who investors assume will remain accountable for them, the often-unsecured debt is classified as "corporate debt", and the national government has indicated it would not bail out a bankrupt LGFV.

Since land has traditionally been owned by the local governments, LGFVs have also turned to earning revenue by through land sales or leases, which can help to repay its creditors. Land can also be used as collateral to secure the bonds.[5][6]

Mechanism

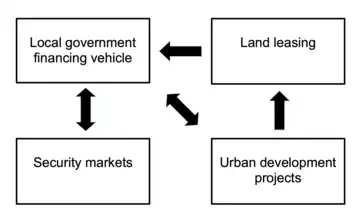

The LGFV borrows money from creditors, mostly by selling bonds in security markets. LGFVs then provide funding to comprehensive urban development projects.

The developments typically increase the value of the surrounding land, which is owned by the local government. The higher land value then boosts local government revenue, through the local government's leasing of land by selling land use rights (LUR).[6]

The LGFV can then pay back its loans, using revenue from land leasing and any revenue from completed projects to pay back its loans. If these revenue sources were not enough, it could issue more bonds as a temporary measure to repay older bonds.

History

Economic reforms - 1970s and 1990s

After the economic reforms of the late 1970s, China's economic growth was largely fueled by rural areas. The result of this growth was that in 1993, only 22% of Chinese tax revenue was being collected by the national government.

In 1994, China underwent financial reforms with a goal of "fiscal recentralization", which aimed to boost the national government's earnings. In doing so, they shrank local tax revenue to below 50% of the total, down from 78%. Local governments still shouldered 70% of regular spending.[7] The reforms also mandated that local governments must have balanced budgets and zero debt, which made it much harder for them to secure financing for infrastructure development.[8]

The 1994 reforms, however, permitted local governments to engage in land financing, where they would earn revenue through leasing land. In addition, the reforms saw the central government give up its share of land transfer proceeds, so the proceeds would belong entirely to local governments.[7] This incentivized local governments to increase land value by developing infrastructure, and LGFVs emerged as a solution to the problem of raising finance for these projects.

Global financial crisis of 2007-2008

The 2007–2008 financial crisis prompted the Chinese government to introduced a 4 trillion yuan ($562 billion) national stimulus plan.[9] 72% of the stimulus plan consisted of infrastructure funding, and the central government funded only 30% of the package.[10] This rapidly increased the rate of borrowing by local governments through LGFVs, with around two thirds of the package funded through borrowing.

Mid 2010s

In 2014, Chinese local governments were permitted to borrow money directly, in an attempt to reduce their reliance on LGFVs. By 2017, bonds represented 90% of local government debt, up from 7% in 2014 (when most debt was borrowing from banks).[11]

In 2015, the Chinese government introduced a Free Trade Zone in Nansha District, which trialed a new model of land finance to encourage private investment in development.

In 2018, the central government announced that it would not bail out LGFVs that go bankrupt, in order to signal the need for caution to the financial markets.[8]

Around this time reforms were made which increased local government's share of value-added tax from 25% to 50%, and granted them a share of the consumption tax.

It was estimated that revenue from the sale of land use rights (LUR) constituted 60-80% of local government revenue in 2018.[12] In 2019, LGFV bonds constituted 39% of total outstanding corporate bonds in China's domestic (onshore) bond market, with widely varying credit risks.[13]

2020 property crisis

The 2020 Chinese property sector crisis heightened concerns about local governments' reliance on LGFVs and land sales, with local government bonds reaching 28.6 trillion yuan (US$4.5 trillion), or 23% of the entire Chinese bond market.[14] The International Monetary Fund estimated that local government debts nearly doubled from 2018-2023, reaching 66 trillion yuan ($9 trillion), nearly half of China's annual economic output.[9]

Although no LGFV has ever defaulted as of 2023, some have been making last-minute payments,[15] which can indicate financial distress.

Property tax proposal

In October 2021, the Wall Street Journal reported that the central government was planning to implement a nationwide property tax, to tackle real estate speculation and provide local governments with more stable revenue. However, the report detailed widespread resistance within the Chinese Communist Party, leading to various alternative proposals including state-owned housing. On 23 October, a five-year trial of the proposed tax was announced for select regions with particularly hot property markets, such as Shenzhen, Hangzhou and Hainan.

Although the property tax could reduce government reliance on land value through LGFVs, it has been estimated that a property could reduce land value by 50%, and that this risk to property owners was contributing to lower land sales.[16] In April 2023, the government completed a unified real estate registration system, which could enable the property tax to be implemented.[17]

Other work

In July 2023 China's state-owned banks began providing loans to LGFVs with a generous repayment period of 25 years, in an attempt to relieve some of the pressure.[18]

References

- Kozhevnikov, M. Yu. (2019). "Debt of Local Governments of China: Assessment Issues and Analysis". Studies on Russian Economic Development. Pleiades Publishing Ltd. 30 (6): 714–716. doi:10.1134/s1075700719060066. ISSN 1075-7007. S2CID 214377956.

- "Risk Comes Home as LGFV Dollar Debt Cocktails Sold in China". Bloomberg News. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- Ang, Yuen Yuen (2016). How China Escaped the Poverty Trap. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-0020-0. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt1zgwm1j.

- Clarke, Donald C. (June 5, 2016). "The Law of China's Local Government Debt Crisis: Local Government Financing Vehicles and Their Bonds". Search eLibrary. SSRN 2821331. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- Cai, Meina; Fan, Jianyong; Ye, Chunhui; Zhang, Qi (July 29, 2020). "Government debt, land financing and distributive justice in China". Urban Studies. 58 (11): 2329–2347. doi:10.1177/0042098020938523. ISSN 0042-0980 – via Sage Journals.

- Hui, Jin; Rial, Isabel (2016). "IMF Working Paper: Regulating Local Government Financing Vehicles and Public-Private Partnerships in China" (PDF). IMF.

- Liu, Minquan (2022), "Three Models of Local Public Financing for Infrastructure Investment in the People's Republic of China", Unlocking Private Investment in Sustainable Infrastructure in Asia, Routledge, doi:10.4324/9781003228790-9, ISBN 978-1-003-22879-0, retrieved 2023-08-01

- Liu, Adam Y.; Oi, Jean C.; Zhang, Yi (2022-01-01). "China's Local Government Debt: The Grand Bargain". The China Journal. 87: 40–71. doi:10.1086/717256. ISSN 1324-9347.

- Zhou, Wei (July 4, 2023). "Why LGFV Debt Is a Growing Risk for China's Economy". Washington Post. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- "4. China's stimulus package | Treasury.gov.au". treasury.gov.au. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- Holmes, Alex; Lancaster, David (2019-06-20). "China's Local Government Bond Market | Bulletin – June 2019".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Huang, Dingxi; Chan, Roger C. K. (2018-05-01). "On 'Land Finance' in urban China: Theory and practice". Habitat International. 75: 96–104. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.03.002. ISSN 0197-3975.

- "Offshore and onshore LGFV bond issuance to reach record highs in 2019". Moody's. August 28, 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "Is China's local government debt a concern and what role do LGFVs play?". South China Morning Post. 2021-11-02. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- "China LGFV's Last-Minute Bond Payment Highlights Local Woes". Bloomberg.com. 2023-05-24. Retrieved 2023-07-31.

- Hawkins, Amy; correspondent, Amy Hawkins Senior China (2023-06-12). "Gold bars used to lure Chinese homebuyers amid market slowdown". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- "China completes landmark national real estate registration system". Reuters. 2023-04-25. Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- "China Banks Offer 25-Year Loans to LGFVs to Avert Credit Crunch". Bloomberg.com. 2023-07-04. Retrieved 2023-07-31.