Lloyd Mathews

Sir Lloyd William Mathews, KCMG, CB (7 March 1850 – 11 October 1901) was a British naval officer, politician and abolitionist. Mathews joined the Royal Navy as a cadet at the age of 13 and progressed through the ranks to lieutenant. He was involved with the Third Anglo-Ashanti War of 1873–4, afterwards being stationed in East Africa for the suppression of the slave trade. In 1877 he was seconded from the navy to Sultan Barghash of Zanzibar in order to form a European-style army; he would remain in the employment of the government of Zanzibar for the rest of his life. His army quickly reached 6,300 men and was used in several expeditions to suppress the slave trade and rebellions against the Zanzibar government.

Lloyd Mathews | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 March 1850 |

| Died | 11 October 1901 (aged 51) |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation(s) | Naval officer and politician |

Mathews retired from the Royal Navy in 1881 and was appointed Brigadier-General of Zanzibar. There followed more expeditions to the African mainland, including a failed attempt to stop German expansion in East Africa. In October 1891 Mathews was appointed First Minister to the Zanzibar government, a position in which he was "irremovable by the sultan". During this time Mathews was a keen abolitionist and promoted this cause to the Sultans he worked with. This resulted in the prohibiting of the slave trade in Zanzibar's dominions in 1890 and the abolition of slavery in 1897. Mathews was appointed the British Consul-General for East Africa in 1891 but declined to take up the position, remaining in Zanzibar instead. Mathews and his troops also played a key role in the ending of the Anglo-Zanzibar War of 1896 which erupted out of an attempt to bypass the requirement that new Sultans must be vetted by the British consul. During his time as first minister Mathews continued to be involved with the military and was part of two large campaigns, one to Witu and another to Mwele.

Mathews was decorated by several governments, receiving appointments as a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George, Companion of the Order of the Bath and as a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George from the British government and membership in the Prussian Order of the Crown. Zanzibar also rewarded him and he was a member of the Grand Order of Hamondieh and a first class member of the Order of the Brilliant Star of Zanzibar. Mathews died of malaria in Zanzibar on 11 October 1901.

Early life and career

Mathews was born at Funchal on Madeira on 7 March 1850.[1] His father, Captain William Matthews, was Welsh and his mother, Jane Wallas Penfold, was the daughter of William Penfold and Sarah Gilbert. Her sister, Augusta Jane Robley (née Penfold), was the author of a book about the flora and fauna of Madeira, which is now in the Natural History Museum.[1][2] His sister, Estella, Countess Cave of Richmond, was an author and the first Division Commissioner of Kingston Girl Guides.[3] Mathews became a cadet of the Royal Navy in 1863 and was appointed a midshipman on 23 September 1866.[1]

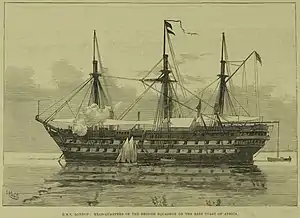

From 1868, he was stationed in the Mediterranean but his first active service was during the Third Anglo-Ashanti War of 1873–4 where he qualified for the campaign medal.[1] He was promoted to lieutenant on 31 March 1874.[4] On 27 August 1875 Mathews was posted to HMS London, a depot ship and the Royal Navy headquarters for East Africa, to assist in the suppression of the slave trade in the area.[1][2] Whilst onboard he drilled his own troops, captured several slave dhows and was commended for his actions by the Admiralty.[1]

Commander in Chief of Zanzibar

In August 1877, Mathews was seconded from the Navy to Sultan Barghash of Zanzibar to form a European-style army which could be used to enforce Zanzibar's control over its mainland possessions.[5] The army had traditionally been composed entirely of Arabs and Persians but Mathews opened up recruitment to the African majority on the island and had 300 recruits in training by the end of the year.[5][6]

In addition, Mathews employed some unorthodox recruitment methods such as purchasing slaves from their masters, using inmates from the prison and recruiting from Africans rescued from the slavers.[7] In June 1877, at the instigation of John Kirk, the explorer and friend of the Sultan, the British government sent a shipment of 500 modern rifles and ammunition as a gift with which to arm the troops.[6]

Mathews introduced a new uniform for the troops consisting of a red cap, short black jackets and white trousers for the enlisted ranks and dark blue frock coats and trousers with gold and silver lace for the Arab officers. The latter was possibly modelled on the Royal Navy officers uniform with which he was familiar.[5] The army grew quickly; by the 1880s Mathews would command 1,300 men, his forces eventually numbering 1,000 regulars and 5,000 irregulars.[1][5]

One of the first tasks for the new army was to suppress the smuggling of slaves from Pangani on the mainland to the island of Pemba, north of Zanzibar. The troops completed this mission, capturing several slavers and hindering the trade.[5] Mathews retired from the Royal Navy in June 1881 and was appointed Brigadier-General of Zanzibar.[1][2]

In 1880, the Sultan dispatched a military force under Mathews to bring his unruly African mainland territories under control.[8] Mathews' expedition was initially intended to reach Unyanyembe but his men refused to march inland and, when made to do so, deserted in large numbers. The expedition ended instead at Mamboya where a 60-man garrison was established.[8] This had been reduced to a mere handful of men by the mid-1880s but the expedition proved that the Sultan was serious about maintaining control of all of his possessions.[8] Mathews' men were also involved in several expeditions to halt the land-based slave trade which had developed once the seas became too heavily policed for the traders.[9]

In 1881, Mathews' old vessel, HMS London, was captained by Charles J Brownrigg.[10]

This vessel and her crew made several patrols aimed at hindering the slave trade using smaller steam boats for the actual pursuits and captures. On 3 December 1881 they caught up with a slave dhow captained by Hindi bin Hattam.[10] This dhow had around 100 slaves on board and was transporting them between Pemba and Zanzibar. Captain Brownrigg led a boarding party to release the slaves but bin Hattam's men then attacked the sailors, killing Brownrigg and his party before sailing away.[10] Mathews led a force to Wete on Pemba and, after a short battle, took a mortally wounded bin Hattem prisoner before returning to Zanzibar.[5]

Mathews returned to the African mainland territories once more in 1884 when he landed with a force which intended to establish further garrisons there to dissuade German territorial claims.[11] This attempt ultimately failed when five German warships steamed into Zanzibar Town harbour and threatened the Sultan into signing away the territories which would later form German East Africa.[11]

Further territories were ceded to the German East Africa Company in 1888 but unrest amongst the locals against them prevented them from taking control and Mathews was dispatched with 100 men to restore order.[12] Finding around 8,000 people gathered against the German administrators Mathews was forced to return with his men to Zanzibar.[12] He landed once again with more troops but found himself subject to death threats and that his troops would not obey his orders and so returned again to Zanzibar.[12]

First Minister

In October 1891, upon the formation of the first constitutional government in Zanzibar, Mathews was appointed First Minister, despite some hostility from Sultan Ali bin Said.[1] In this capacity Mathews was "irremovable by the sultan" and answerable only to the Sultan and the British Consul.[13] His position was so strong that one missionary on the island is quoted as saying that his powers defied "analytical examination" and that Mathews really could say "L'état est moi" (I am the state).[14] Mathews was also known as the "Strong man of Zanzibar".[15] The principal departments of government were mostly run by Britons or British Indians and Mathews' approval was required before they could be removed from office.[16]

Mathews was rewarded by the Zanzibar government for his role with his appointment as a first class member of the Order of the Brilliant Star of Zanzibar, which he was granted licence by Queen Victoria to accept and wear on 17 May 1886.[17] Mathews used his position to suppress slavery in the country and in 1889 convinced the Sultan to issue a decree purchasing the freedom of all slaves who had taken refuge in his dominions and, from 1890, the prohibiting the slave trade.[1]

On 1 February 1891, Mathews was appointed Her Majesty's Commissioner and Consul-General to the British Sphere of Influence in East Africa.[18] He never took up the post and instead chose to remain in Zanzibar.[1]

Mathews was rewarded for his service in Zanzibar by the British government which appointed him a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1880 and a Companion of the Order of the Bath on 24 May 1889.[1][19]

Despite becoming renowned in East Africa as a man who ran a fair administration and was strict with criminals, unhappiness with effective British rule and his halting of the slave trade led some Arabs to petition the Sultan for his removal in 1892.[1][20] In 1893, Mathews purchased the island of Changuu for the government.[21] He intended it to be used as a prison but it never housed prisoners and was instead used to quarantine yellow fever cases before its present use as a conservation area for giant tortoises.[21]

Mathews was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1894.[1] He was also awarded membership of the Order of the Crown by the German government.[1]

Matters came to a head when Khalid bin Barghash attempted to take control of the palace in Zanzibar Town upon the death of his uncle in August 1896, despite failing to gain the consent of the British consul there.[22] Mathews opposed this succession and, with British agreement, called up 900 soldiers in an attempt to prevent it.[23]

This situation eventually led to the Anglo-Zanzibar War and Mathews, with the support of Admiral Harry Rawson and five vessels of the Royal Navy, bombarded the palace and secured the end of Khalid's administration.[23] Mathews' helped to arrange the succession of a pro-British Sultan, Hamoud bin Mohammed, as Khalid's successor.[1] Mathews continued his reforms after the war, abolishing slavery in 1897 and establishing new farms to grow produce using Western techniques.[1] He was appointed a member of the Grand Order of Hamondieh of Zanzibar and was permitted to accept and wear the decoration on 25 August 1897.[24]

Military expeditions

Mwele

In addition to the smaller-scale expeditions described earlier, Mathews embarked on two much larger expeditions to the African mainland during his tenure as first minister, the first at Mwele. The initial rebellion in the area had been led by Mbaruk bin Rashid at Gazi, which Mathews had put down with 1,200 men in 1882. However, in 1895 Mbaruk's nephew, Mbaruk bin Rashid, refused to acknowledge the appointment of a new leader at Takaungu.[2] This led to open rebellion at Konjoro in February of that year when the younger Mbaruk attacked Zanzibari troops under Arthur Raikes, one of Mathews' officers.[2] Mathews was part of an Anglo-Zanzibari expedition sent to quell it, which consisted of 310 British sailors, 50 Royal Marines, 54 Sudanese and 164 Zanzibari troops.[2] Konjoro was destroyed and the leaders fled to Gazi where the older Mbaruk failed to turn them over.[2] Another force, under Admiral Rawson, with 400 British marines and sailors, was sent after them.[2] This further expedition failed to capture the ringleaders and a third expedition was organised by Rawson with 220 sailors, 80 marines, 60 Sudanese and 50 Zanzibaris, which destroyed Mwele.[2] During the latter action Mathews was wounded in the shoulder.[2]

Witu

Following the death of a German logger who had been operating illegally, the Sultan of Zanzibar and the British government dispatched an expedition on 20 October 1890 to bring the Sultan of Witu to justice.[25] Nine warships and three transports carrying 800 sailors and marines, 150 Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEA) Indian police, 200 Zanzibari and 50 Sudanese troops were sent, defeating the Sultan and establishing a British protectorate.[25] The IBEA was given control of the area and established a force of 250 Indian police to maintain the peace.[25] The police were withdrawn in July 1893 following threats of violence from the new Sultan of Witu, Oman, and another expedition was dispatched to the region.[25] This consisted of three warships: HMS Blanche, HMS Sparrow and the Zanzibari ship HHS Barawa.[25] The latter carried Mathews with 125 Askaris and 50 Sudanese under Brigadier-General Hatch of the Zanzibar army.[25]

Mathews and an escort force went to Witu where, on 31 July, they removed the flag of the IBEA company and replaced it with the red flag of Zanzibar, before destroying several villages and causing Oman to retreat into the forests.[25] The British troops then withdrew, having suffered heavily from malaria, but the Sudanese and Zanzibari troops remained.[25] A further expedition was sent of 140 sailors and 85 other troops but Oman died soon after and a more pliable sultan, Omar bin Hamid, was appointed to govern on behalf of Zanzibar, bringing the affair to a close.[25] In return for this action, Mathews received the British East and West Africa campaign medal.[25]

Later life

Mathews died of malaria in Zanzibar on 11 October 1901 and was buried with full military honours in the British cemetery outside Zanzibar Town.[1][5] His successor as first minister was Alexander Stuart Rogers.[26] Changuu Island, which Mathews bought for a prison, now has a restaurant named in his honour and also a church.[27] Mathews House, at the Western end of Zanzibar Town, is also named for him.[15]

References

- Milne 2004.

- Patience, Kevin, The Mwele Campaign 1895–1896, archived from the original on 9 February 2009

- "Presentation". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. 1 February 1926. p. 11.

- "No. 24082". The London Gazette. 31 March 1874. p. 1923.

- McIntyre & Shand 2006

- Bennett 1978, p. 100.

- Bennett 1978, p. 101.

- Bennett 1978, p. 119.

- Clark et al. 1975, p. 550.

- Patience, Kevin, A Brief History of the Cemetery on Grave Island – Zanzibar, archived from the original on 21 July 2011, retrieved 28 September 2008

- Bennett 1978, p. 129.

- Bennett 1978, p. 143.

- Pouwels 1987, p. 164.

- Pouwels 1987, pp. 168–169.

- Hodd 2002, p. 548.

- Pouwels 1987, p. 169.

- "No. 25588". The London Gazette. 18 May 1886. p. 2402.

- "No. 26137". The London Gazette. 24 February 1891. p. 1004.

- "No. 25939". The London Gazette. 25 May 1889. p. 2875.

- Pouwels 1987, p. 170.

- Zanzibar Commission for Tourism. "Dhow Cruising". Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- Hernon 2003, p. 399.

- Hernon 2003, p. 400.

- "No. 26886". The London Gazette. 27 August 1887. p. 4812.

- Patience, Kevin, The Witu expeditions – 1890 and 1893, archived from the original on 15 July 2009

- Pouwels 1987, p. 185.

- Safari Now. "Changuu Private Island Paradise". Retrieved 18 October 2008.

Bibliography

- Bennett, Norman Robert (1978), A History of the Arab State of Zanzibar, Routledge, ISBN 0-416-55080-0.

- Clark, Desmond J; Fage, J D; Oliver, Roland Anthony; Roberts, A D (1975), The Cambridge History of Africa, vol. 6, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22803-4.

- Hernon, Ian (2003), Britain's Forgotten Wars, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509-3162-0.

- Hodd, Michael (2002), East Africa Handbook, Bath: Footprint Books, ISBN 0-7509-3162-0.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1912). . Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- McIntyre, Chris; Shand, Susan (2006), Zanzibar: The Bradt Travel Guide, Bradt Publications, ISBN 1-84162-157-9.

- Milne, Lynne (2004). "Lloyd Mathews". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34936. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Pouwels, Randall L (1987), Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam on the East African Coast, 800-1900, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-52309-5.