List of operas by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's operas comprise 22 musical dramas in a variety of genres. They range from the small-scale, derivative works of his youth to the full-fledged operas of his maturity. Three of the works were abandoned before completion and were not performed until many years after the composer's death. His mature works are all considered classics and have never been out of the repertory of the world's opera houses.[1]

From a very young age Mozart had, according to opera analyst David Cairns, "an extraordinary capacity ... for seizing on and assimilating whatever in a newly encountered style (was) most useful to him".[2] In a letter to his father, dated 7 February 1778, Mozart wrote, "As you know, I can more or less adopt or imitate any kind and style of composition".[3] He used this gift to break new ground, becoming simultaneously "assimilator, perfector and innovator".[2] Thus, his early works follow the traditional forms of the Italian opera seria and opera buffa as well as the German Singspiel. In his maturity, according to music writer Nicholas Kenyon, he "enhanced all of these forms with the richness of his innovation",[1] and, in Don Giovanni, he achieved a synthesis of the two Italian styles, including a seria character in Donna Anna, buffa characters in Leporello and Zerlina, and a mixed seria-buffa character in Donna Elvira.[1] Unique among composers, Mozart ended all his mature operas, starting with Idomeneo, in the key of the overture.[4][5]

Ideas and characterisations introduced in the early works were subsequently developed and refined. For example, Mozart's later operas feature a series of memorable, strongly drawn female characters, in particular the so-called "Viennese soubrettes" who, in opera writer Charles Osborne's phrase, "contrive to combine charm with managerial instinct".[6] Music writer and analyst Gottfried Kraus has remarked that all these women were present, as prototypes, in the earlier operas; Bastienne (1768), and Sandrina (La finta giardiniera, 1774) are precedents for the later Constanze and Pamina, while Sandrina's foil Serpetta is the forerunner of Blonde, Susanna, Zerlina and Despina.[7]

Mozart's texts came from a variety of sources, and the early operas were often adaptations of existing works.[lower-alpha 1] The first librettist chosen by Mozart himself appears to have been Giambattista Varesco, for Idomeneo in 1781.[9] Five years later, he began his most enduring collaboration, with Lorenzo Da Ponte, his "true phoenix".[10] The once widely held theory that Da Ponte was the librettist for the discarded Lo sposo deluso of 1783/84 has now been generally rejected.[lower-alpha 2] Mozart felt that, as the composer, he should have considerable input into the content of the libretto, so that it would best serve the music. Musicologist Charles Rosen writes, "it is possible that Da Ponte understood the dramatic necessities of Mozart's style without prompting; but before his association with da Ponte, Mozart had already bullied several librettists into giving him the dramatically shaped ensembles he loved."[12][lower-alpha 3]

Compiling the list

Basis for inclusion

The list includes all the theatrical works generally accepted as composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. In this context "theatrical" means performed on a stage, by vocalists singing in character, in accordance with stage directions. Some sources have adopted more specific criteria, leading them to exclude the early "Sacred Singspiel" Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebots,[lower-alpha 4] which they classify as an oratorio.[lower-alpha 5] However, as Osborne makes clear, the libretto contains stage directions which suggest that the work was acted, not merely sung, and it is formally described as a "geistliches Singspiel" (sacred play with music), not as an oratorio.[15] The Singspiel Der Stein der Weisen was written in collaboration with four other composers, so it is only partially credited to Mozart.

Sequence

In general, the list follows the sequence in which the operas were written. There is uncertainty about whether La finta semplice was written before or after Bastien und Bastienne, and in some listings the former is given priority.[lower-alpha 6] Thamos was written in two segments, the earlier in 1774, but is listed in accordance with its completion in 1779–80. Die Zauberflöte and La clemenza di Tito were written concurrently. Die Zauberflote was started earlier and put aside for the Tito commission,[16] which was completed and performed first and is usually listed as the earlier work despite having a higher Köchel catalogue number.

List of operas

Key: Incomplete opera Collaborative work

| Period[lower-alpha 7] | Title | Genre and acts[lower-alpha 8] | Libretto | Voice parts[lower-alpha 9] | Premiere[lower-alpha 10] | Köchel No.[lower-alpha 11] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lang. | Librettist[lower-alpha 12] | Date | Venue | |||||

| 1766–67 | Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebots, Part 1[lower-alpha 13] (The obligation of the first and foremost commandment) |

Sacred Singspiel (collaboration) |

German | Ignaz von Weiser[lower-alpha 14] | 3 soprano, 2 tenor | 12 March 1767 | Archbishop's Palace, Salzburg | K.35 Score Libretto |

| 1767 | Apollo et Hyacinthus (Apollo and Hyacinth) |

Music for a Latin drama[18] | Latin | Rufinus Widl, after Ovid's Metamorphoses | 2 treble, 2 boy alto, 1 tenor, 2 bass, chorus[lower-alpha 15] | 13 May 1767 | Great Hall, University of Salzburg | K.38 Score |

| 1768 | Bastien und Bastienne (Bastien and Bastienne) |

Singspiel 1 act |

German | F. W. Weiskern and J. H. Muller[lower-alpha 16] | 1 soprano, 1 tenor, 1 bass | 2 October 1890.[lower-alpha 17] | Architektenhaus, Wilhelmstraße 92, Berlin | K.50/46b Score |

| 1768 | La finta semplice (The feigned simpleton) |

Opera buffa 3 acts |

Italian | Marco Coltellini, after Carlo Goldoni | 3 soprano, 2 tenor, 2 bass | 1 May 1769 | Archbishop's Palace, Salzburg | K.51/46a Score |

| 1770 | Mitridate, re di Ponto (Mithridates, King of Pontus) |

Opera seria 3 acts |

Italian | V. A. Cigna-Santi, based on G. Parini's translation of Racine's Mithridate | 4 soprano, 1 alto, 2 tenor[lower-alpha 18] | 26 December 1770 | Teatro Regio Ducale, Milan | K.87/74a Score |

| 1771 | Ascanio in Alba (Ascanius in Alba) |

Festspiel[lower-alpha 19] 2 acts |

Italian | Giuseppe Parini | 4 soprano, 1 tenor, chorus[lower-alpha 20] | 17 October 1771 | Teatro Regio Ducale, Milan | K.111 Score |

| 1772 | Il sogno di Scipione (Scipio's Dream) |

Azione teatrale, or Serenata drammatica 1 act |

Italian | Metastasio, based on Cicero's Somnium Scipionis | 3 soprano, 3 tenor, chorus |

1 May 1772 (probably)[lower-alpha 21] | Archbishop's Palace, Salzburg | K.126 Score |

| 1772 | Lucio Silla | Dramma per musica 3 acts |

Italian | Giovanni de Gamerra, revised by Metastasio | 4 soprano, 2 tenor, chorus[lower-alpha 22] | 26 December 1772 | Teatro Regio Ducale, Milan | K.135 Score |

| 1774–75 | La finta giardiniera (The pretend garden-maid) |

Dramma giocoso 3 acts[lower-alpha 23] |

Italian | Probably Giuseppe Petrosellini[lower-alpha 24] | 4 soprano, 2 tenor, 1 bass, chorus[lower-alpha 25] | 13 January 1775 | Salvatortheater, Munich | K.196 Score |

| 1775 | Il re pastore (The Shepherd King) |

Serenata 2 acts |

Italian | Metastasio, amended by Varesco, based on Tasso's Aminta[8] | 3 soprano, 2 tenor[lower-alpha 26] | 23 April 1775 | Archbishop's Palace, Salzburg | K.208 Score |

| 1773, 1779 | Thamos, König in Ägypten (Thamos, King of Egypt) |

Choruses and entr'actes for a heroic drama | German | Tobias Philipp von Gebler | Soprano, alto, tenor, bass (chorus and soloists) |

4 April 1774 (two choruses) |

Kärntnertor Theatre, Vienna | K.345/336a Score |

| 1779–80 (complete) |

Salzburg | |||||||

| 1779–80 | Zaide | Singspiel (incomplete) |

German | Johann Andreas Schachtner | 1 soprano, 2 tenor, 2 bass, mini-chorus of 4 tenors, 1 speaking role | 27 January 1866[lower-alpha 27] | Frankfurt[lower-alpha 28] | K.344/336b Score |

| 1780–81 | Idomeneo, re di Creta (Idomeneus, King of Crete) |

Dramma per musica 3 acts |

Italian | Varesco, after Antoine Danchet's Idoménée | 3 soprano, 1 mezzo-soprano, 4 tenor, 1 baritone, 2 bass, chorus[lower-alpha 29] | 29 January 1781 | Court Theatre (now Cuvilliés Theatre), Munich | K.366 Score |

| 1781–82 | Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) |

Singspiel 3 acts |

German | Gottlieb Stephanie, based on C. Bretzner's Belmont und Constanze, oder Die Entführung aus dem Serail | 2 soprano, 2 tenor, 1 bass, 2 speaking roles[lower-alpha 30] | 16 July 1782 | Burgtheater, Vienna | K.384 Score Libretto |

| 1783 | L'oca del Cairo (The goose of Cairo) |

Dramma giocoso (incomplete) 3 acts |

Italian | Varesco | (Provisional) 4 soprano, 2 tenor, 2 bass, chorus | 6 June 1867[lower-alpha 27] | Théâtre des Fantaisies-Parisiennes, Paris | K.422 Score |

| 1783–84 | Lo sposo deluso (The Deluded Bridegroom) |

Opera buffa (incomplete) 2 acts |

Italian | Unknown. Once attributed to Da Ponte[31] but may have been by Giuseppe Petrosellini.[lower-alpha 2][32] | (Provisional) 3 soprano, 2 tenor, 2 bass | 6 June 1867[33][lower-alpha 27] | Théâtre des Fantaisies-Parisiennes, Paris | K.430/424a Score |

| 1786 | Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario) |

Comic singspiel 1 act |

German | Gottlieb Stephanie | 2 soprano, 1 tenor, 1 bass, 6 speaking roles | 7 February 1786 | Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna | K.486 Score |

| 1785–86 | Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) |

Opera buffa 4 acts |

Italian | Da Ponte, based on Beaumarchais's La folle journée, ou le Mariage de Figaro | 5 soprano, 2 tenor, 1 baritone, 3 bass, chorus[lower-alpha 31] | 1 May 1786 | Burgtheater, Vienna | K.492 Score Libretto |

| 1787 | Don Giovanni[lower-alpha 32] | Dramma giocoso 2 acts |

Italian | Da Ponte, based on Giovanni Bertati's Don Giovanni Tenorio | 3 soprano, 1 tenor, 1 baritone, 3 bass, chorus | 29 October 1787[lower-alpha 33] | Estates Theatre,[lower-alpha 34] Prague | K.527 Score Libretto |

| 1789–90 | Così fan tutte (Women are like that or All women do that)[lower-alpha 35] |

Dramma giocoso 2 acts |

Italian | Da Ponte | 3 soprano, 1 tenor, 1 baritone, 1 bass, chorus | 26 January 1790 | Burgtheater, Vienna | K.588 Score Libretto |

| 1790 | Der Stein der Weisen (The Philosopher's Stone) (Pasticcio composed with J. B. Henneberg, F. Gerl, B. Schack and E. Schikaneder) |

Singspiel (collaboration) 2 acts |

German | Emanuel Schikaneder | 3 soprano, 2 tenor, 2 baritone, 1 bass, 1 speaking role | 11 September 1790 | Theater auf der Wieden, Vienna | K.592a |

| 1791 | La clemenza di Tito (The clemency of Titus) |

Opera seria 2 acts |

Italian | Metastasio, revised by Caterino Mazzolà | 2 soprano, 2 mezzo-soprano, 1 tenor, 1 bass, chorus[lower-alpha 36] | 6 September 1791 | Estates Theatre, Prague | K.621 Score Libretto |

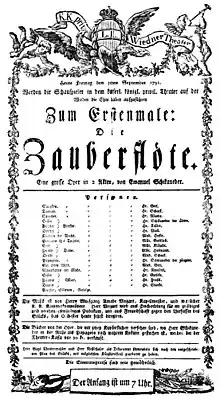

| 1791 | Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) |

Singspiel 2 acts |

German | Emanuel Schikaneder | 6 soprano, 2 mezzo-soprano, 1 alto, 4 tenor, 1 baritone, 4 bass, chorus | 30 September 1791 | Theater auf der Wieden, Vienna | K.620 Score Libretto |

Notes and references

Notes

- For example, Metastasio's text for Il re pastore had been written in 1751 and had been set to music before.[8]

- According to some recent scholarship, the unknown Italian poet responsible for the text is more likely to have been Giuseppe Petrosellini, who initially prepared it for Domenico Cimarosa's opera Le donne rivali, 1780.[11]

- For two instances in which Mozart coaxed his librettists into reshaping their work, see Die Entführung aus dem Serail (which quotes Mozart's correspondence on this point) and Varesco.

- "Gebotes" or "Gebottes" are archaic spelling variants of the modern "Gebots" which is regularly used in the title.

- Kenyon begins his guide to the operas with Apollo et Hyacinthus;[13] Cairns more or less dismisses Die Schuldigkeit,[14] seemingly following the view of Edward J. Dent, quoted by Osborne (1992, p. 27). Grove, also, does not list Die Schuldigkeit as an opera.

- Both were written in 1768. The first performance of La finta semplice was delayed until May 1779, whereas Bastien und Bastienne may have been performed in October 1768. It is entirely possible, however, that La finta semplice was written first. See Osborne (1992, pp. 37–38, 45)

- Period during which the opera was written

- Unless indicated otherwise, these descriptions are taken from the title pages of Neue Mozart-Ausgabe. In instances where the English meaning is unclear, an English equivalent is given.

- Voice part summaries are as given by Osborne (1992). Additional notes indicate roles originally sung by castrati.

- Unless noted otherwise, details of first performances are as given by Osborne (1992).

- Köchel numbers refer to the Köchel Catalogue of Mozart's work, prepared by Ludwig von Köchel and first published in 1862. The catalogue has been revised several times, most recently in 1964. The first number refers to K1, the original numbering; the second to K6 from 1964.

- Unless noted otherwise, librettist details are as given by Osborne (1992)

- Part 2 is by Michael Haydn, Part 3 by Anton Cajetan Adlgasser.[17]

- Weiser is the most likely of several possible authors of the text; see Osborne (1992, pp. 24–25).

- Premiered with an all-male cast, the soprano and alto parts being sung by boy choristers.[19]

- The text was derived from a French parody, Les amours de Bastien et Bastienne, a work by Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Le devin du village, 1752.[20]

- possibly Vienna, October 1768, in the garden of Dr Franz Mesmer). Dr Franz Anton Mesmer was the founder of the form of hypnotherapy known as "mesmerism".[21]

- The soprano roles of Sifare and Arbate, and the alto role of Farnace, were written for castrati.[22]

- In Italian this translates to festa teatrale.[23] Osborne (1992, p. 63) calls it a "pastoral opera".

- The soprano roles of Ascanio and Fauno were written for castrati.[24]

- Details of first performance are obscure.Osborne (1992) gives dates "29 April or 1 May", Kenyon (2006, p. 296) says: "There is no record it was actually performed in 1772"

- The soprano role of Cecilio was written for a castrato.[25]

- Mozart prepared a Singspiel version, Die verstellte Gärtnerin, produced in Augsburg on 1 May 1780. The German version, now known as Die Gärtnerin aus Liebe, has remained popular.[26][27]

- The libretto was formerly credited to Ranieri de' Calzabigi, revised by Marco Coltellini, but is now credited to Petrosellini.[28]

- The soprano role of Ramiro was written for a castrato.

- The soprano role of Aminta was written for castrato.[29]

- Not performed during Mozart's lifetime.

- The exact location is unrecorded

- The role of Idamante, originally written for castrato, was rewritten by Mozart as a tenor role in 1786.[30] Also, the role of Arbace is sometimes sung by a tenor.

- One speaking role, that of a sailor, is absent from most modern productions

- Two soprano soloists from the chorus sing the duet of the servant girls, "Amanti, costanti" in the act 3 finale.[34]

- The full name of the opera is Il dissoluto punito, ossia Il Don Giovanni, but as Kenyon (2006, p. 326) states: "It is fruitless to argue against the habits of opera houses around the world".

- For the Vienna premiere, six months later, certain changes were introduced, mainly to accommodate the ranges of a different group of singers. Modern performances generally conflate the Prague and Vienna productions.[35]

- also known as Nostitz-Theater and Tyl theatre

- This is an approximate translation from the Italian. Cairns (2006, p. 177) gives: "That is what all women do". The subtitle, La scola degli amanti, is more easily translatable as "The School for lovers".[36][37]

- One mezzo-soprano role, depicting the male character Annio, was originally a castrato and is now done by mezzos. The role of Sesto (Sextus) was originally written by Mozart for a tenor before he found out it had been assigned to a mezzo castrato.

References

- Kenyon 2006, pp. 283–285.

- Cairns 2006, p. 11.

- Cairns 2006, p. 17.

- Webster 2017, p. 216.

- Levin 2008.

- Osborne 1992, pp. 191–192.

- Kenyon 2006, pp. 302.

- Kenyon 2006, p. 303.

- Kenyon 2006, p. 308.

- Letter to his father, c. 1774, in Holden (2007, p. xv)

- Dell'Antonio 1996, pp. 404–405, 415.

- Rosen 1997, p. 155.

- Kenyon 2006, p. 287.

- Cairns 2006, p. 24.

- Osborne 1992, p. 26.

- Osborne 1992, p. 300.

- Osborne 1992, p. 16.

- Kenyon 2006, p. 288.

- Osborne 1992, p. 32.

- Kenyon 2006, p. 291.

- Batta 2000, p. 343.

- Osborne 1992, p. 59.

- Kenyon 2006, p. 294.

- Osborne 1992, p. 69.

- Osborne 1992, p. 86.

- Kenyon 2006, pp. 300–301.

- Osborne 1992, p. 97.

- Kenyon 2006, p. 300.

- Osborne 1992, p. 105.

- Osborne 1992, p. 155.

- Osborne 1992, pp. 208–209.

- Dell'Antonio 1996, p. 415.

- Osborne 1992, p. 207.

- Osborne 1992, p. 251.

- Osborne 1992, p. 268.

- Cairns 2006, p. 176.

- Osborne 1992, p. 281.

Sources

- András Batta (editor) (2000). Opera: Composers, Works, Performers (English ed.). Cologne: Könemann. ISBN 3-8290-3571-3

- Cairns, David (2006). Mozart and his Operas. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-029674-3.

- Dell'Antonio, Andrew (1996). "Il Compositore Deluso: The Fragments of Mozart's Comic Opera Lo Sposo Deluso (K424a/430)". In Stanley Sadie (ed.). Wolfgang Amadé Mozart: Essays on His Life and Work. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816443-2.

- Holden, Anthony (2007). The Man Who Wrote Mozart: The extraordinary life of Lorenzo Da Ponte. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-2180-0.

- Kenyon, Nicholas (2006). The Pegasus Pocket Guide to Mozart. New York: Pegasus Books. ISBN 1-933648-23-6.

- Levin, Robert (27 November 2008). "Musing on Mozart and Studying with Boulanger". The Boston Musical Intelligencer.

- Osborne, Charles (1992). The Complete Operas of Mozart. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-03823-3.

- Rosen, Charles (1997). The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-00653-0.

- Webster, James (2017). John A. Rice (ed.). Essays on Opera, 1750–1800. Ashgate Library of Essays in Opera Studies (reprint ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781351567886.

Further reading

- Dent, Edward J. (1973). Mozart's Operas: A Critical Study. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-284001-0.

- Heartz, Daniel, ed. (1990). Mozart's Operas. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07872-1.

- Mann, William (1986). The Operas of Mozart. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-31135-9.

- Robbins, Landon, H. C. (1990). 1791: Mozart's Last Year. London: Fontana. ISBN 0-00-654324-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Steptoe, Andrew (1988). The Mozart–Da Ponte Operas. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816221-9.

External links

- "Neue Mozart-Ausgabe" [New Mozart Edition]. Bärenreiter.

- Opera libretti, critical editions, diplomatic editions, source evaluation (German only), links to online DME recordings; Digital Mozart Edition