List of ethnic cleansing campaigns

This article lists incidents that have been termed ethnic cleansing by some academic or legal experts. Not all experts agree on every case, particularly since there are a variety of definitions of the term ethnic cleansing. When claims of ethnic cleansing are made by non-experts (e.g. journalists or politicians) they are noted.

Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern periods

Antiquity

Early modern period

- c. 1492–1614 AD: Jews and Muslims in Spain who refused to convert to Catholicism were expelled, beginning in 1492 following the Alhambra Decree.[3][4][5]

_p_415_Map_of_the_Settlement_of_Ireland_by_the_Act_of_26th_September%252C_1653.jpg.webp)

After Cromwell's conquest of Ireland, huge areas of land were confiscated and the Irish Catholics were banished to the lands of Connacht.

- 1556–1620: Plantations of Ireland. Land in Laois, Offaly, Munster and parts of Ulster was seized by the English crown and colonised with English settlers.[6] Ireland has been described as a "testing ground" for British colonialism, with the confiscation of land and expulsion of native Irish from their homelands being a rehearsal for the expulsion of the Native Americans by British settlers.[7][8]

- c. 1652 AD: After the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and Act of Settlement in 1652, the whole post-war Cromwellian settlement of Ireland has been characterised by historians such as Mark Levene and Alan Axelrod as ethnic cleansing, in that it sought to remove Irish Catholics from the eastern part of the country, but others such as the historian Tim Pat Coogan have described the actions of Cromwell and his subordinates as genocide.[9]

- 1755–1764 AD: During the French and Indian War, the Nova Scotia colonial government, aided by New England troops, instituted a systematic removal of the French Catholic Acadian population of Nova Scotia – eventually removing thousands of settlers from the region and relocating them to areas in the Thirteen Colonies, Britain and France. Many eventually moved and settled in Louisiana and became known as Cajuns. Many scholars have described the subsequent death of over 50% of the deported Acadian population as an ethnic cleansing.[10]

19th century

- On 26 May 1830, president Andrew Jackson of the United States signed the Indian Removal Act which resulted in the Trail of Tears.[11][12][13][14]

- Between 1821 and 1922, a large number of Muslims were expelled from Southeast Europe as Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia gained their independence from the Ottoman Empire. Mann describes these events as "murderous ethnic cleansing on a stupendous scale not previously seen in Europe." These countries sought to expand their territory against the Ottoman Empire, which culminated in the Balkan Wars of the early 20th century.[15] The Russian Empire also engaged in ethnic cleansing in the Caucasus following military victories.[16]

- In 2005, the historian Gary Clayton Anderson of the University of Oklahoma published The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1830–1875. This book repudiates traditional historians, such as Walter Prescott Webb and Rupert N. Richardson, who viewed the settlement of Texas by the displacement of the native populations as a healthful development. Anderson writes that at the time of the outbreak of the American Civil War, when the population of Texas was nearly 600,000, the still-new state was "a very violent place. ... Texans mostly blamed Indians for the violence – an unfair indictment, since a series of terrible droughts had virtually incapacitated the Plains Indians, making them incapable of extended warfare."[17]

- The Long Walk of the Navajo, was the 1864 ethnic cleansing of the Navajo people by the United States federal government.[18][19]

- The Russian Empire was the subject of several cases of ethnic and religious cleansing against minorities, including Catholics (Poles and Lithuanians), Lutherans (Latvians and Estonians), Jews (Pale of Settlement) and Muslims.[20]

- The Expulsion of the Albanians, 1877–1878 refers to events of forced migration of Albanian populations from areas that became incorporated into the Principality of Serbia and Principality of Montenegro in 1878. These wars, alongside the larger Russo-Ottoman War (1877–78) ended in defeat and substantial territorial losses for the Ottoman Empire which was formalised at the Congress of Berlin. This expulsion was part of the wider persecution of Muslims in the Balkans during the geopolitical and territorial decline of the Ottoman Empire.[21][22] Although most of these Albanians were expelled by Serbian forces, a small presence was allowed to remain in the Jablanica valley where their descendants live today.[23][24][25]

- Beginning from about 1848, and extending into the 20th century, the residents of Silesia have been expelled by various governments as their homeland has come under the rule of different states.[26]

20th century

1900s–1910s

- The Herero and Namaqua genocide was a campaign of racial extermination and collective punishment that the German Empire undertook in German South West Africa (modern-day Namibia) against the Herero, Nama and San people. It is considered the first genocide of the 20th century.[27][28][29][30]

- During the Balkan Wars, ethnic cleansings were carried out in Kosovo, Macedonia, Sandžak and Thrace. At first, they were committed against the Muslim population, but later, they were also committed against Christians. Villages were burned and people were massacred.[31] The Bulgarians, Serbs and Greeks burned villages and massacred Turkish civilians, but since then, the population of the Turkish-majority areas of the Bulgarian-occupied areas has remained almost unchanged.[32][33] The Turks usually massacred Bulgarian and Greek males who lived in the areas which they reoccupied, but they did not massacre any Greeks during the Second Balkan War, the women and children were also raped and frequently slaughtered during each massacre.[34] During the Second Balkan War, an ethnic cleansing campaign was carried out by the Ottoman Army and Turkish Bashi-bazouks exterminated the whole Bulgarian population of the Ottoman Adrianople Vilayet (an estimated 300,000 people before the war) and displacing the survivors of the massacres (60,000).[35] Under Greek occupation, Bulgarian Macedonians were persecuted, expelled from their homes and forced to move to regions of Greece which are located north of the Bulgarian border. The Bulgarians had expelled 100,000 Greeks from Macedonia and West Thrace before the territories were returned to Greece.[36] In addition to the dead, the aftermath of the war counts 890,000 people who permanently left their homes, of whom 400,000 fled to Turkey, 170,000 fled to Greece, 150,000[37] or 280,000 fled to Bulgaria.[38] The population size of Bulgarians in Macedonia was mostly reduced by forceful assimilation campaigns through terror, following the ban of the use of the Bulgarian language and declarations which are named "Declare yourself a Serb or die.", signers were required to renounce their Bulgarian identity on paper in Serbia and Greece.[33][34]

- The 1914 Greek deportations have been described as an ethnic cleansing campaign by scholars Matthias Bjørnlund and Taner Akçam.[39][40]

- The Armenian genocide which occurred during World War I was implemented in two phases: the wholesale killing of the able-bodied male population through massacres and forced labor, and the deportation of women, children, the elderly and the infirm to the Syrian Desert on death marches.[41][42] In addition to being described as a genocide, it is often described as an ethnic cleansing campaign in academic literature.[43][44]

- The Bolshevik regime killed or deported an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 Don Cossacks during the Russian Civil War, in 1919–1920.[45] Geoffrey Hosking stated "It could be argued that the Red policy towards the Don Cossacks amounted to ethnic cleansing. It was short-lived, however, and soon abandoned because it did not fit with normal Leninist theory and practice".[46]

1920s–1930s

- In 1920–21, the Greek army on the Yalova-Gemlik Peninsula burned dozens of Turkish/Muslim villages, engaging in large-scale violence and ethnic cleansing.[47]

- The Population exchange between Greece and Turkey has been described as an ethnic cleansing.[48] In 1928, 1,104,216 Ottoman refugees were living in Greece.[49]

Greek refugees from Smyrna, 1922

- Pacification of Libya, Italian authorities committed ethnic cleansing in the Cyrenaica region of Libya by forcibly removing and relocating 100,000 members of the Cyrenaican indigenous population from their valuable land and property that was slated to be given to Italian settlers.[50]

- The Chinese Kuomintang Generals Ma Qi and Ma Bufang launched campaigns of expulsion in Qinghai and Tibet against ethnic Tibetans. The actions of these Generals have been called Genocidal by some authors.[51]

- Authors Uradyn Erden Bulag called the events that follow as a Genocide while David Goodman named them ethnic cleansing: The Republic of China-supported Ma Bufang when he launched seven extermination expeditions into Golog, eliminating thousands of Tibetans.[52] Some Tibetans counted the number of times he attacked them, remembering the seventh attack which made their lives impossible.[53] Ma was highly anti-communist, and he and his army wiped out many Tibetans in the northeast and eastern Qinghai, and they also destroyed Tibetan Buddhist Temples.[54][55][56]

Deportation of the Soviet Koreans in 1937

- The Mexican Repatriation from 1929 to 1939 in which mass deportations and repatriations of Mexicans and Mexican Americans occurred in response to poverty and nativist fears which were triggered by the Great Depression in the United States has been called ethnic cleansing. An estimated forty to sixty percent of the 355,000 to 2 million people who were repatriated were birthright U.S. citizens - an overwhelming number of them were children. Voluntary repatriations were much more common than deportations.[57][58][59] Legal scholar Kevin Johnson States that it meets modern legal standards for ethnic cleansing, arguing it involved the forced removal of an ethnic minority by the government.[60]

- The deportation of 172,000 Soviet Koreans by the Soviet government in September 1937, in which Koreans were moved away from the Korean border and deported to Central Asia, where they were made to do forced labor.[61]

1940s

The bodies of the dead lie awaiting burial in a mass grave at the German extermination camp or "killing center" of Bergen-Belsen

Emaciated corpses of Jewish children in Warsaw Ghetto

Prisoners sort through shoes thought to belong to Hungarian Jews who were murdered in the gas chambers after arrival to the Auschwitz extermination camp.

Massacres of Poles in Volhynia in 1943. Most Poles of Volhynia (now in Ukraine) had either been murdered or had fled the area.

- The 1936-45 Romani genocide or the Porajmos: the killing of an estimated 130,565 Romani people by Nazi Germany, with some estimates ranging from 220,000 to 500,000.[62]

- The 1938-45 Holocaust: The murder of an estimated 6 million Jews by the Nazi government of Germany both inside Germany and throughout German occupied territories, and some of its independent allies such as the governments of Romania,[63] Hungary,[64] and Bulgaria[65] (outside Bulgarian core territories).

- The Independent State of Croatia carried out ethnic cleansing against Serbs, Roma, and Jews by expelling them, mass executions, and imprisonment in concentration camps such as Jasenovac.[66][67]

- Chetnik atrocities against Bosniaks and Croats in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1941 to 1945 have been characterised as organised ethnic cleansing. It is estimated that around 32,000 Croats (20,000 from Croatia, and 12,000 from Bosnia) and 33,000 Bosniaks were killed.[68][69]

- Population transfers in the Soviet Union during and after World War II on the orders of Joseph Stalin, including the deportation of the Karachays, deportation of the Balkars, deportation of the Chechens and Ingush, deportation of the Meskhetian Turks and the deportation of the Kalmyks.[70] Nearly 3.5 million ethnic minorities were resettled during 1940–52.[71]

- Towards the end of World War II, nearly 14,000–25,000 ethnic Albanian Muslims were expelled from the coastal region of Epirus in northwestern Greece by the EDES paramilitary organization, supported by the state.[72]

- The expulsion of 14 million ethnic Germans from the Former eastern territories of Germany after World War II. This policy was decided at the Potsdam Conference by the victorious powers.[73][74][75]

- During the Partition of India 6 million Muslims fled ethnic violence taking place in India to settle in what became Pakistan (and by 1971, Bangladesh) and 5 million Hindus and Sikhs fled from what became Pakistan and Bangladesh, to settle in India. The events which occurred during this time period have been described as ethnic cleansing by Ishtiaq Ahmed[76][77] and by Barbara and Thomas R. Metcalf.[78]

- In 1947, the Jammu Massacre took place. The event has been described as ethnic cleansing of Muslims in the Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir.[79][80]

- According to some scholars, most notably Ilan Pappé, the Nakba or 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight during the 1947-1949 Palestine war, which involved the expulsion of much of the native population of Palestine, was partly a deliberate ethnic cleansing event, enacted by operations such as Plan Dalet.[81] While the war saw more than 700,000 Palestinians displaced and between 400 and 600 Palestinian villages destroyed, the causes of the mass displacement remain a matter of ongoing debate.[81]

1950s

- From 5–6 September 1955, the Istanbul pogrom or "Septembrianá"/"Σεπτεμβριανά", secretly backed by the Turkish government, was launched against the Greek population of Istanbul. The mob also attacked some Jewish and Armenian residents of the city. The event contributed greatly to the gradual extinction of the Greek minority in the city and throughout the entire country, which numbered 100,000 in 1924 after the Turko-Greek population exchange treaty. By 2006 there were only 2,500 Greeks living in Istanbul.[82]

- The Jewish exodus from Muslim countries, the flight of over 850,000 Jews of the Islamic world, mainly Mizrahi and Sephardic. Many Arab governments, such as Gaddafi's Libya, Nasserist Egypt, and Hafez al-Assad's Syria, confiscated Jewish bank accounts and property of Jews who had departed, in addition to placing laws restricting Jewish business. The episode is sometimes labelled one of ethnic cleansing.[83][84][85][86]

1960s

- On 5 July 1960, five days after the Congo gained independence from Belgium, the Force Publique garrison near Léopoldville mutinied against its white officers and attacked numerous European targets. This caused fear amongst the approximately 100,000 whites still resident in the Congo and led to their mass exodus from the country.[87]

- Ne Win's rise to power in 1962 and his relentless persecution of "resident aliens" (immigrant groups not recognised as citizens of the Union of Burma) led to an exodus of some 300,000 Burmese Indians. They migrated to escape racial discrimination and wholesale nationalisation of private enterprises a few years later in 1964.[88]

- The 1962 Rajshahi massacres in East Pakistan (modern-day Bangladesh) witnessed the killing of minorities, mostly Buddhists and Hindus, by Muslims.[89] More than 3,000 non-Muslims were killed.[90] In 1958, Ayub Khan came to power in Pakistan, and from the beginning the policy of the Ayub Regime was to cleanse East Pakistan of Bengali Hindus and other minorities. There was also arson, rapes, and looting.[91] This ethnic cleansing campaign resulted in the migration of 11,000 Santhals and Rajbanshis to India.[92]

- In 1964, the 1964 East Pakistan Riots occurred which resulted in more than 10,000 Bengali Hindus being targeted and systematically killed by Bengali Muslims.[93] In the village of Mainam near Nagaon in Rajshahi District all Hindus except 2 little girls were massacred.[94] This resulted in more than 135,000 refugees.[93] Hundreds of villages around Dhaka city were burnt to ashes.[95] This left more than 100,000 Hindus homeless.[96] 95% of the ruined houses belonged to Hindus who lived in Old Dhaka.[96]

- The expulsion of the Chagossians from the Chagos Archipelago by the United Kingdom, at the request of the United States in order to establish a military base, started in 1968 and concluded in 1973.[97][98]

1970s

- There was an ethnic cleansing of the Greek population of the areas under Turkish military occupation in Cyprus in 1974–76 during and after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. This has been the subject of litigation in the European Court of Human Rights in cases including Loizidou v. Turkey and the European Court of Justice in cases like Apostolides v Orams.[99][100][101]

- Following the U.S. withdrawal from South Vietnam in 1973 and the communist victory two years later, the Kingdom of Laos's coalition government was overthrown by the communists. The Hmong people, who had actively supported the anti-communist government, became targets of retaliation and persecution. The government of Laos has been accused of committing Genocide against the Hmong,[102][103] with up to 100,000 killed.[104]

- The Communist Khmer Rouge government in Cambodia disproportionately targeted ethnic minority groups, including ethnic Chinese, Vietnamese and Thais. In the late 1960s, an estimated 425,000 ethnic Chinese lived in Cambodia; by 1984, as a result of Khmer Rouge genocide and emigration, only about 61,400 Chinese remained in the country. The small Thai minority along the border was almost completely exterminated, only a few thousand managing to reach safety in Thailand. The Muslim Cham Minority suffered serious purges with as much as 80% of their population exterminated. The Khmer's racial supremacist ideology was responsible to this ethnic purge. A Khmer Rouge order stated that henceforth "The Cham nation no longer exists on Kampuchean soil belonging to the Khmers" (U.N. Doc. A.34/569 at 9).[105][106]

- Subsequent waves of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya fled Burma and many refugees inundated neighbouring Bangladesh including 250,000 in 1978 as a result of the Operation Dragon King in Arakan.[107][108]

1980s

- The forced assimilation campaign during 1984–1985 directed against ethnic Turks by the Bulgarian State resulted in the mass emigration of some 360,000 Bulgarian Turks to Turkey in 1989 has been characterized as ethnic cleansing.[109][110][111]

- The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has resulted in the displacement of populations from both sides. Among the displaced are 700,000 Azerbaijanis and several Kurds from ethnic Armenian-controlled territories including Armenia and areas of Nagorno-Karabakh,[112] more than 353,000 Armenians were forced to flee from territories controlled by Azerbaijan plus some 80,000 had to flee Armenian border territories.[113]

1990s

The cemetery at the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial and Cemetery to Genocide Victims

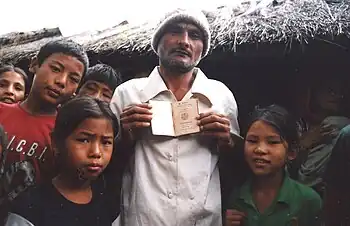

Bhutanese refugees in Nepal

- In 1990, inter-ethnic tensions escalated in Bhutan, resulting in the flight of many Lhotshampa, or ethnic Nepalis, from Bhutan to Nepal, many of whom were expelled by the Bhutanese military. By 1996, over 100,000 Bhutanese refugees were living in refugee camps in Nepal. Many have since been resettled in Western nations.[114] One reason for this expulsion was the desire of the Bhutanese government to remove a largely Hindu population and preserve its Buddhist culture and identity.[115]

- In 1991, as part of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, during Operation Ring, Soviet troops and the predominantly Azerbaijani soldiers in the AzSSR OMON and army forcibly uprooted Armenians living in the 24 villages strewn across Shahumyan to leave their homes and settle elsewhere in Nagorno-Karabakh or in the neighboring Armenian SSR.[116] Human rights organizations documented a wide number of human rights violations and abuses committed by Soviet and Azerbaijani forces and many of them properly characterised them as ethnic cleansing. These violations and abuses included forced deportations of civilians, unlawful killings, torture, kidnapping harassment, rape and the wanton seizure or destruction of property.[117][118] Despite fierce protests, no measures were taken either to prevent the human rights abuses or to punish the perpetrators.[117] Approximately 17,000 Armenians living in twenty-three of Shahumyan's villages were deported out of the region.[119]

- In 1991, following a major crackdown on Rohingya Muslims in Burma, 250,000 refugees took shelter in the Cox's Bazar district of neighboring Bangladesh.[120]

- After the Gulf War in 1991, Kuwait conducted a campaign of expulsion against the Palestinians living in the country, who before the war had numbered 400,000. Some 200,000 who had fled during the Iraqi occupation were banned from returning, while the remaining 200,000 were pressured into leaving by the authorities, who conducted a campaign of terror, violence, and economic pressure to get them to leave.[121] The Kuwaiti Palestinians expelled from Kuwait moved to Jordan, where they had citizenship.[122]

- As a result of the 1991–1992 South Ossetia War, about 100,000 ethnic Ossetians fled South Ossetia and Georgia proper, most across the border into North Ossetia. A further 23,000 ethnic Georgians fled South Ossetia and settled in other parts of Georgia.[123]

- According to Helsinki Watch, the campaign of ethnic-cleansing was orchestrated by the Ossetian militants, during the events of the Ossetian–Ingush conflict, which resulted in the expulsion of approximately 60,000 Ingush inhabitants from Prigorodny District.[124]

Ethnic cleansing of a Croatian home

- The widespread ethnic cleansing accompanying the Croatian War of Independence that was committed by Serb-led Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and rebel militia in the occupied areas of Croatia (self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina) (1991–1995). Large numbers of Croats and non-Serbs were removed, either by murder, deportation or by being forced to flee. According to the ICTY indictment against Slobodan Milošević, there was an expulsion of around 170,000 to 250,000 Croats and other non-Serbs from their home,[125][126] in addition to an estimated 10,000 Croats that were also killed.[127] Also, around 10,000 Croats left Vojvodina in 1992 due to persecution by Serb nationalists.[128] Milan Martić,[129] Milan Babić[130] and Vojislav Šešelj[131][132] were convicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) for persecution on racial, ethnic or religious ground, deportation and/or forcible displacement as a crime against humanity.

- In February 1992, hundreds of ethnic Azeris[133] and Meskhetian Turks[134] are massacred as Armenian troops capture the city of Khojaly in Nagorno-Karabakh.[135]

- Widespread ethnic cleansing accompanied the War in Bosnia (1992–1995). Large numbers of Croats and Bosniaks were forced to flee their homes by the Army of the Republika Srpska, large numbers of Serbs and Bosniaks by the Croatian Defence Council and Serbs and Croats by the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[136] Beginning in 1991, political upheavals in the Balkans displaced about 2,700,000 people by mid-1992, of which over 700,000 sought asylum in other parts of Europe.[137][138] In September 1994, UNHCR representatives estimated around 80,000 non-Serbs out of 837,000 who initially lived on the Serb-controlled territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina before the war remained there; an estimated removal of 90% of the Bosniak and Croat inhabitants of Serb-coveted territory, almost all of whom were deliberately forced out of their homes.[139] It also includes ethnic cleansing of non-Croats in the breakaway state the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia[140] The ICTY convicted several officials for persecution, forced transfer and/or deportation, including Momčilo Krajišnik,[141] Radoslav Brđanin,[142] Stojan Župljanin, Mićo Stanišić,[143] Biljana Plavšić,[144] Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić.[145]

An elderly Serb refugee in a tractor trailer leaving her home during Operation Storm

An elderly Serb refugee in a tractor trailer leaving her home during Operation Storm - Exodus of between 100,000 and 200,000 Krajina Serbs during and after the Croatian Army's Operation Storm.[146] Some investigators and academics describe this event as ethnic cleansing.[147][148][149] Historian Marko Attila Hoare disagrees that the operation was an act of ethnic cleansing, and points out that the Krajina Serb leadership evacuated the civilian population as a response to the Croatian offensive; whatever their intentions, the Croatians never had the chance to organise their removal.[150] [151] The ICTY indicted Croatian generals Ante Gotovina, Ivan Čermak and Mladen Markač for war crimes for their roles in the operation, charging them with participating in a joint criminal enterprise (JCE) aimed at the permanent removal of Serbs from the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) held part of Croatia. Gotovina and Markač were convicted and Čermak was acquitted in April 2011.[152] In November 2012, the ICTY Appeals Chamber acquitted Gotovina and Markač, reversing its earlier judgement by a 3–2 decision.[153] The Appeals Chamber ruled that there was insufficient evidence to conclude the existence of a joint criminal enterprise to remove Serb civilians by force and further stated that while the Croatian Army and Special Police committed crimes after the artillery assault, the state and military leadership could not be held responsible for their planning and creation.[154]

Kosovo Albanian refugees in 1999

- At least 700,000 Kosovo Albanians were deported from Kosovo between 1998 and 1999 during the Kosovo War.[155] The ICTY convicted several officials for persecution, forced displacement and/or deportation, including Nikola Šainović, Dragoljub Ojdanić and Nebojša Pavković.[156]

- In the aftermath of Kosovo War between 200,000 and 250,000 Serbs and other non-Albanians fled Kosovo.[157][158][159]

- The forced displacement and ethnic-cleansing of more than 250,000 people, mostly Georgians but some others too, from Abkhazia during the conflict and after in 1993 and 1998.[160]

- The mass expulsion of southern Lhotshampas (Bhutanese of Nepalese origin) by the northern Druk majority in Bhutan in 1990.[161] The number of refugees is approximately 103,000.[162]

- In Jammu and Kashmir, a separatist insurgency has targeted the Hindu Kashmiri Pandit minority and 400,000 have been displaced, and 1,200 have been killed since 1991. Islamic terrorists infiltrated the region in 1989 and began an ethnic cleansing campaign to convert Kashmir to a Muslim state. Since that time, over 400,000 Kashmiri Hindus have either been murdered or forced from their homes.[163] This has been condemned and labeled as ethnic cleansing in a 2006 resolution passed by the United States Congress.[164] Also in 2009 the Oregon Legislative Assembly introduced a resolution to recognize 14 September 2007, as Martyrs Day to acknowledge the ethnic cleansing and the campaigns of terror inflicted on the non-Muslim minorities of Jammu and Kashmir by militants seeking to establish an independent Kashmir, and also to recognize the region as Indian territory rather than as a disputed territory – the resolution failed to pass.[165]

- The May 1998 riots of Indonesia targeted many Chinese Indonesians. Suffering from looting and arson many Chinese Indonesians fled from Indonesia.[166][167]

- There have been serious outbreaks of inter-ethnic violence on the island of Kalimantan since 1997, involving the indigenous Dayak peoples and immigrants from the island of Madura. In 2001 in the Central Kalimantan town of Sampit, at least 500 Madurese were killed and up to 100,000 Madurese were forced to flee. Some Madurese bodies were decapitated in a ritual reminiscent of the headhunting tradition of the Dayaks of old.[168]

21st century

2000s

- In 2003, Sinafasi Makelo, a representative of Mbuti Pygmies, told the UN's Indigenous People's Forum that during the Congo Civil War, his people were hunted down and eaten as though they were game animals. Both sides of the war regarded them as "subhuman" and some say their flesh can confer magical powers. Makelo asked the UN Security Council to recognize cannibalism as a crime against humanity and an act of genocide.[169][170]

- From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, Indonesian paramilitaries organized and armed by Indonesian military and police killed or expelled large numbers of civilians in East Timor.[171][172] After the East Timorese people voted for independence in a 1999 referendum, Indonesian paramilitaries retaliated, murdering Separatists and levelling most towns. More than 200,000 people either fled or were forcibly taken to Indonesia before East Timor achieved full independence.[173]

- Since the mid-1990s the central government of Botswana has been trying to move Bushmen also known as the Saan, out of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. As of October 2005, the government has resumed its policy of forcing all Bushmen off their lands in the Game Reserve, using armed police and threats of violence or death.[174] Many of the involuntarily displaced Bushmen live in squalid resettlement camps and some have resorted to prostitution and alcoholism, while about 250 others remain or have surreptitiously returned to the Kalahari to resume their independent lifestyle.[175] Festus Mogae defended the Actions, saying, "How can we continue to have Stone Age creatures in an age of computers?"[176][177]

- Since 2003, Sudan has been widely accused of carrying out a Genocide Campaign against several black ethnic groups in Darfur, in response to a rebellion by Africans alleging mistreatment. Sudanese irregular militia known as the Janjaweed and Sudanese military and police forces have killed an estimated 450,000, expelled around two million, and burned 800 villages.[178] A 14 July 2007 article notes that in the past two months up to 75,000 Arabs from Chad and Niger crossed the border into Darfur. Most have been relocated by the Sudanese government to former villages of displaced non-Arab people. Some 450,000 have been killed and 2.5 million have now been forced to flee to refugee camps in Chad after their homes and villages were destroyed.[179]

- At least one additional thousand Serbs fled their homes during the 2004 unrest in Kosovo and numerous religious and cultural objects were burned down.[180][181]

- During the Iraq Civil War and consequent Iraqi insurgency (2011-2013), entire neighborhoods in Baghdad were ethnically cleansed by Shia and Sunni militias.[182][183] Some areas were evacuated by every member of a particular group due to lack of security, moving into new areas because of fear of reprisal killings. As of 21 June 2007, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that 2.2 million Iraqis had been displaced to neighboring countries, and 2 million were displaced internally, with nearly 100,000 Iraqis fleeing to Syria and Jordan each month.[184][185][186]

- Assyrian exodus from Iraq from 2003 until present is often described as ethnic cleansing. Although Iraqi Christians represent less than 5% of the total Iraqi population, they make up 40% of the refugees now living in nearby countries, according to UNHCR.[187][188] In the 16th century, Christians constituted half of Iraq's population.[189] In 1987, the last Iraqi census counted 1.4 million Christians.[190] Following the 2003 invasion and the resultant growth of militant Islamism, Christians' total numbers slumped to about 500,000, of whom 250,000 live in Baghdad.[191] Furthermore, the Mandaean and Yazidi communities are at the risk of elimination due to the ongoing atrocities by Islamic extremists.[192][193] A 25 May 2007 article notes that in the past 7 months only 69 people from Iraq have been granted refugee status in the United States.[194]

- In October 2006, Niger announced that it would deport Arabs living in the Diffa region of eastern Niger to Chad.[195] This population numbered about 150,000.[196] Nigerien government forces forcibly rounded up Arabs in preparation for deportation, during which two girls died, reportedly after fleeing government forces, and three women suffered miscarriages. Niger's government eventually suspended the plan.[197][198]

- In 1950, the Karen had become the largest of 20 minority groups participating in an insurgency against the military dictatorship in Burma. The conflict continues as of 2008. In 2004, the BBC, citing aid agencies, estimates that up to 200,000 Karen have been driven from their homes during decades of war, with 120,000 more refugees from Burma, mostly Karen, living in refugee camps on the Thai side of the border. Many accuse the military government of Burma of ethnic cleansing.[199] As a result of the ongoing war in minority group areas more than two million people have fled Burma to Thailand.[200]

- Civil unrest in Kenya erupted in December 2007.[201] By 28 January 2008, the death toll from the violence was at around 800.[202] The United Nations estimated that as many as 600,000 people have been displaced.[203][204] A government spokesman claimed that Odinga's supporters were "engaging in ethnic cleansing".[205]

- The 2008 attacks on North Indians in Maharashtra began on 3 February 2008. Incidences of violence against North Indians and their property were reported in Mumbai, Pune, Aurangabad, Beed, Nashik, Amravati, Jalna and Latur. Nearly 25,000 North Indian workers fled Pune,[206][207] and another 15,000 fled Nashik in the wake of the attacks.[208][209]

- South Africa Ethnic Cleansing erupted on 11 May 2008 within three weeks 80 000 were displaced the death toll was 62, with 670 injured in the violence when South Africans ejected non-nationals in a nationwide ethnic cleansing/xenophobic outburst. The most affected foreigners have been Somalis, Ethiopians, Indians, Pakistanis, Zimbabweans and Mozambiqueans. Local South Africans have also been caught up in the violence. Arvin Gupta, a senior UNHCR protection officer, said the UNHCR did not agree with the City of Cape Town that those displaced by the violence should be held at camps across the city.[210] During the 2010 FIFA world cup, rumors were reported that xenophobic attacks will be commenced after the final. A few incidents occurred where foreign individuals were targeted, but the South African police claims that these attacks can not be classified as xenophobic attacks but rather as regular criminal activity in the townships. Elements of the South African Army were sent into the affected townships to assist the police in keeping order and preventing continued attacks.

- In August 2008, the 2008 South Ossetia war broke out when Georgia launched a military offensive against South Ossetian separatists, leading to military intervention by Russia, during which Georgian forces were expelled from the separatist territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. During the fighting, 15,000[211] ethnic Georgians living in South Ossetia were forced to flee to Georgia proper, and Ossetian militias burned their villages to the Ground in order to prevent their return.

2010s

- Strategic demographic and cultural cleansing by the Sinhala Buddhist majority of the Muslim and Tamil minorities in Sri Lanka.[212]

Refugees of the fighting in the Central African Republic, 19 January 2014

- The killing of hundreds of ethnic Uzbeks in Kyrgyzstan during the 2010 South Kyrgyzstan ethnic clashes resulting in the flight of thousands of Uzbek refugees to Uzbekistan have been called ethnic cleansing by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and international media.[213][214]

- Members of the Azusa 13 gang, associated with the Mexican Mafia, were accused of attempting a racial cleansing of African Americans in Azusa, California.[215]

- 2012 Rakhine State riots. An estimated 90,000 people have been displaced in the recent sectarian violence between Rohingya Muslims and Buddhists in Burma's western Rakhine State.[107][216]

- Approximately 400,000 people have been displaced in the 2012 Assam ethnic violence between indigenous Bodos and Bengali-speaking Muslims in Assam, India.[217]

- Sources inside the Syriac Orthodox Church have reported that an ongoing ethnic cleansing of Syrian Christians is being carried out by anti-government rebels.[218][219]

- Central African Republic Civil War.[220]

- As part of a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Rohingya Muslims, more than 50 people were killed in the 2013 Myanmar anti-Muslim riots.[221]

- In 2015, Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu publicly accused Russia and Syria of ethnic cleansing against the Syrian Turkmen minority.[222] Only a few thousand Turkmen now live in Syria, in contrast to the 200,000-300,000 Turks who lived there before the Syrian Civil War.[223] Thousands of Turkmen villagers have fled the country to escape Russian bombing. The minority also faced persecution prior to the war; and denied to speak their dialect.[224][225]

- In 2017 a new wave of government sanctioned ethnic cleansing[226] against Rohingya Muslims amounting to genocide[227] with thousands killed and many villages burned to the ground with their inhabitants executed has been reported in Myanmar,[228][229][227][230][231] to the extent that children have reported to be beheaded or burned alive by the Myanmar military and Buddhist vigilantes.[232][233][234]

- The ongoing Turkish occupation of northern Syria has seen ethnic cleansing of Kurds, Christians, Yazidis, and other minorities, especially in the Afrin District, where 150,000–300,000 Kurds were displaced. The Turkish state has been resettling Afrin with Arab Syrian refugees.[235][236]

- The Uyghur genocide has involved a campaign of ethnic cleansing[237][238][239][240] orchestrated by the Chinese government against the Uyghur people and other ethnic and religious minorities in and around the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) of the People's Republic of China.[241][242][243] Since 2014,[244] the Chinese government, under the direction of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) during the administration of CCP general secretary Xi Jinping, has pursued policies leading to more than one million Muslims[245][246][247][248][249] (the majority of them Uyghurs) being held in secretive internment camps without any legal process[250][251] in what has become the largest-scale and most systematic detention of ethnic and religious minorities since the Holocaust.[252][253][254]

2020s

Mass grave of civilians in Tigray

- The War in Tigray has been described as an ongoing ethnic cleansing perpetrated by Ethiopia against ethnic Tigrayans. New IDs have been prescribed to Tigrayans, and many Tigrayans living in other Ethiopian regions have been subject to "ethnically selective purges."[255] Ethiopia has also weaponized famine as a key war tactic in Tigray, leaving an estimated 90% of the population vulnerable to famine. All electricity has been cut off by Ethiopia, cutting off Tigray's communication with the outside world. One schoolteacher recalled, "Even if someone was dead, they shot them again, dozens of times. I saw this. I saw many bodies, even priests. They killed all Tigrayans."[256][255]

- During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, reports indicated that between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainians on the Russian-occupied territories were deported to Russia, including 260,000 children. At least 18 filtration camps were established along the Russian border to facilitate this transfer.[257] These crimes were alleged to be a form of depopulation and ethnic cleansing of Ukraine by the Russian military on the order of Russia's leader Vladimir Putin.[258][259]

- Following the 2023 Nagorno-Karabakh clashes on 19-20 September and the ensuing takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh by Azerbaijan, fears of persecution and ethnic cleansing led ethnic Armenian inhabitants of the region to flee to Armenia from 24 September onward. By 3 October, 100,617 refugees, more than 99% of Nagorno-Karabakh's population, had fled to Armenia.[260][261][262]

See also

References

- Melikian, Souren (22 August 2008). "The 'peaceful' Hadrian and his endless wars". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- Beard, M. (2008), "A very modern emperor", The Guardian, retrieved 12 September 2023,

In the end, Hadrian's forces had to resort to the most ruthless form of ethnic cleansing, constructive starvation and mass slaughter of the enemy that went far beyond the casualties inflicted by the Jews.

- Pérez, Joseph (2007). History of a Tragedy: The Expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Translated by Hochroth, Lysa. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252031410.

- Bell-Fialkoff, Andrew (1 June 1993). "A Brief History of Ethnic Cleansing". Foreign Affairs (Summer 1993): 4. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- Saldanha, Arun (2012). Deleuze and Race. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 51, 70. ISBN 978-0-7486-6961-5.

- Rogers, Joe (30 April 2018). From an Irish Market Town. Publishamerica Incorporated. ISBN 9781456043087 – via Google Books.

- Horning, Audrey (2013). Ireland in the Virginian Sea. University of North Carolina Press. doi:10.5149/9781469610733_horning. ISBN 9781469610726. JSTOR 10.5149/9781469610733_horning.

- Hallinan, Conn Malachi (1977). "The Subjugation and Division of Ireland: Testing Ground for Colonial Policy". Crime and Social Justice (8): 53–57. JSTOR 29766019.

-

- Albert Breton (Editor, 1995). Nationalism and Rationality. Cambridge University Press 1995. Page 248. "Oliver Cromwell offered Irish Catholics a choice between genocide and forced mass population transfer"

- Ukrainian Quarterly. Ukrainian Society of America 1944. "Therefore, we are entitled to accuse the England of Oliver Cromwell of the genocide of the Irish civilian population.."

- David Norbrook (2000).Writing the English Republic: Poetry, Rhetoric and Politics, 1627–1660. Cambridge University Press. 2000. In interpreting Andrew Marvell's contemporarily expressed views on Cromwell Norbrook says; "He (Cromwell) laid the foundation for a ruthless programme of resettling the Irish Catholics which amounted to large scale ethnic cleansing.."

- Frances Stewart Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine (2000). War and Underdevelopment: Economic and Social Consequences of Conflict v. 1 (Queen Elizabeth House Series in Development Studies), Oxford University Press. 2000. p. 51 "Faced with the prospect of an Irish alliance with Charles II, Cromwell carried out a series of massacres to subdue the Irish. Then, once Cromwell had returned to England, the English Commissary, General Henry Ireton, adopted a deliberate policy of crop burning and starvation, which was responsible for the majority of an estimated 600,000 deaths out of a total Irish population of 1,400,000."

- Alan Axelrod (2002). Profiles in Leadership, Prentice-Hall. 2002. Page 122. "As a leader Cromwell was entirely unyielding. He was willing to act on his beliefs, even if this meant killing the king and perpetrating, against the Irish, something very nearly approaching genocide"

- Tim Pat Coogan (2002). The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace. ISBN 978-0-312-29418-2. p 6. "The massacres by Catholics of Protestants, which occurred in the religious wars of the 1640s, were magnified for propagandist purposes to justify Cromwell's subsequent genocide."

- Peter Berresford Ellis (2002). Eyewitness to Irish History, John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-26633-4. p. 108 "It was to be the justification for Cromwell's genocidal campaign and settlement."

- John Morrill (2003). Rewriting Cromwell – A Case of Deafening Silences, Canadian Journal of History. Dec 2003. "Of course, this has never been the Irish view of Cromwell.

Most Irish remember him as the man responsible for the mass slaughter of civilians at Drogheda and Wexford and as the agent of the greatest episode of ethnic cleansing ever attempted in Western Europe as, within a decade, the percentage of land possessed by Catholics born in Ireland dropped from sixty to twenty. In a decade, the ownership of two-fifths of the land mass was transferred from several thousand Irish Catholic landowners to British Protestants. The gap between Irish and the English views of the seventeenth-century conquest remains unbridgeable and is governed by G. K. Chesterton's mirthless epigram of 1917, that "it was a tragic necessity that the Irish should remember it; but it was far more tragic that the English forgot it." - James M Lutz Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Brenda J Lutz, (2004). Global Terrorism, Routledge: London, p.193: "The draconian laws applied by Oliver Cromwell in Ireland were an early version of ethnic cleansing. The Catholic Irish were to be expelled to the northwestern areas of the island. Relocation rather than extermination was the goal."

- Mark Levene (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation State: Volume 2. ISBN 978-1-84511-057-4 Page 55, 56 & 57. A sample quote describes the Cromwellian campaign and settlement as "a conscious attempt to reduce a distinct ethnic population".

- Mark Levene (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation-State, I.B. Tauris: London:

[The Act of Settlement of Ireland], and the parliamentary legislation which succeeded it the following year, is the nearest thing on paper in the English, and more broadly British, domestic record, to a programme of state-sanctioned and systematic ethnic cleansing of another people. The fact that it did not include 'total' genocide in its remit, or that it failed to put into practice the vast majority of its proposed expulsions, ultimately, however, says less about the lethal determination of its makers and more about the political, structural and financial weakness of the early modern English state.

- MacLeod, Katie (20 September 2016). "The Unsaid of the Grand Dérangement: An Analysis of Outsider and Regional Interpretations of Acadian History". The Graduate History Review. University of Victoria. 5 (1). Archived from the original on 2 September 2018.

- Robert E. Greenwood (2007). Outsourcing Culture: How American Culture has Changed From "We the People" Into a One World Government. Outskirts Press. p. 97.

- Rajiv Molhotra (2009). "American Exceptionalism and the Myth of the American Frontiers". In Rajani Kannepalli Kanth (ed.). The Challenge of Eurocentrism. Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 180, 184, 189, 199.

- Paul Finkelman; Donald R. Kennon (2008). Congress and the Emergence of Sectionalism. Ohio University Press. pp. 15, 141, 254.

- Ben Kiernan (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. pp. 328, 330.

- Michael Mann, The dark side of democracy: explaining ethnic cleansing, pp. 112–4, Cambridge, 2005 "... figures are derive[d] from McCarthy (1995: I 91, 162–4, 339), who is often viewed as a scholar on the Turkish side of the debate. Yet even if we reduce his figures by 50 percent, they would still horrify. He estimates that between 1812 and 1922 somewhere around 5½ million Muslims were driven out of Europe and 5 million more were killed or died of either disease or starvation while fleeing. ... In the final Balkan Wars of 1912–13 he estimates that 62 percent of all Muslims (27 percent dead, 35 percent refugees) disappeared from the lands conquered by Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria. This was murderous ethnic cleansing on a stupendous scale not previously seen in Europe, ..."

- Mihcael, Radu. Dangerous Neighborhood: Contemporary Issues in Turkey's Foreign Relations, p. 78

- The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1830–1875. University of Oklahoma Press. 2005. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8061-3698-1. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- Anderson, Gary C. Ethnic Cleansing and the Indian: The Crime that Should Haunt America. The University of Oklahoma Press. Oklahoma City, 2014.

- Lee, Lloyd ed. Navajo Sovereignty. Understandings and visions of the Diné People. University of Arizona Press: Tucson, 2017.

- Lohr, Eric (2003). Nationalizing the Russian Empire. Harvard: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674010413.

- Jagodić 1998, para. 15.

- Stojanović 2010, p. 264

- Blumi 2013, p. 50. "As these Niš refugees waited for acknowledgment from locals, they took measures to ensure that they were properly accommodated by often confiscating food stored in towns. They also simply appropriated lands and began to build shelter on them. A number of cases also point to banditry in the form of livestock raiding and "illegal" hunting in communal forests, all parts of refugees' repertoire... At this early stage of the crisis, such actions overwhelmed the Ottoman state, with the institution least capable of addressing these issues being the newly created Muhacirin Müdüriyeti... Ignored in the scholarship, these acts of survival by desperate refugees constituted a serious threat to the established Kosovar communities. The leaders of these communities thus spent considerable efforts lobbying the Sultan to do something about the refugees. While these Niš muhacirs would in some ways integrate into the larger regional context, as evidenced later, they, and a number of other Albanian-speaking refugees streaming in for the next 20 years from Montenegro and Serbia, constituted a strong opposition block to the Sultan's rule."; p.53. "One can observe that in strategically important areas, the new Serbian state purposefully left the old Ottoman laws intact. More important, when the state wished to enforce its authority, officials felt it necessary to seek the assistance of those with some experience, using the old Ottoman administrative codes to assist judges make rulings. There still remained, however, the problem of the region being largely depopulated as a consequence of the wars... Belgrade needed these people, mostly the landowners of the productive farmlands surrounding these towns, back. In subsequent attempts to lure these economically vital people back, while paying lip-service to the nationalist calls for "purification," Belgrade officials adopted a compromise position that satisfied both economic rationalists who argued that Serbia needed these people and those who wanted to separate "Albanians" from "Serbs." Instead of returning to their "mixed" villages and towns of the previous Ottoman era, these "Albanians," "Pomaks," and "Turks" were encouraged to move into concentrated clusters of villages in Masurica, and Gornja Jablanica that the Serbian state set up for them. For this "repatriation" to work, however, authorities needed the cooperation of local leaders to help persuade members of their community who were refugees in Ottoman territories to "return." In this regard, the collaboration between Shahid Pasha and the Serbian regime stands out. An Albanian who commanded the Sofia barracks during the war, Shahid Pasha negotiated directly with the future king of Serbia, Prince Milan Obrenović, to secure the safety of those returnees who would settle in the many villages of Gornja Jablanica. To help facilitate such collaborative ventures, laws were needed that would guarantee the safety of these communities likely to be targeted by the rising nationalist elements infiltrating the Serbian army at the time. Indeed, throughout the 1880s, efforts were made to regulate the interaction between exiled Muslim landowners and those local and newly immigrant farmers working their lands. Furthermore, laws passed in early 1880 began a process of managing the resettlement of the region that accommodated those refugees who came from Austrian-controlled Herzegovina and from Bulgaria. Cooperation, in other words, was the preferred form of exchange within the borderland, not violent confrontation."

- Turović 2002, pp. 87–89.

- Uka 2004c, p. 155."Në kohët e sotme fshatra të Jabllanicës, të banuara kryesisht me shqiptare, janë këto: Tupalla, Kapiti, Gërbavci, Sfirca, Llapashtica e Epërrne. Ndërkaq, fshatra me popullsi te përzier me shqiptar, malazezë dhe serbë, jane këto: Stara Banja, Ramabanja, Banja e Sjarinës, Gjylekreshta (Gjylekari), Sijarina dhe qendra komunale Medvegja. Dy familje shqiptare ndeshen edhe në Iagjen e Marovicës, e quajtur Sinanovë, si dhe disa familje në vetë qendrën e Leskovcit. Vllasa është zyrtarisht lagje e fshatit Gërbavc, Dediqi, është lagje e Medvegjes dhe Dukati, lagje e Sijarinës. Në popull konsiderohen edhe si vendbanime të veçanta. Kështu qendron gjendja demografike e trevës në fjalë, përndryshe para Luftës se Dytë Botërore Sijarina dhe Gjylekari ishin fshatra me populisi të perzier, bile në këtë te fundit ishin shumë familje serbe, kurse tani shumicën e përbëjnë shqiptarët. [In contemporary times, villages in the Jablanica area, inhabited mainly by Albanians, are these: Tupale, Kapiti, Grbavce, Svirca, Gornje Lapaštica. Meanwhile, the mixed villages populated by Albanians, Montenegrins and Serbs, are these: Stara Banja, Ravna Banja, Sjarinska Banja, Đulekrešta (Đulekari) Sijarina and the municipal center Medveđa. Two Albanian families are also encountered in the neighborhood of Marovica called Sinanovo, and some families in the center of Leskovac. Vllasa is formally a neighborhood of the village Grbavce, Dedići is a neighborhood of Medveđa and Dukati, a neighborhood of Sijarina. So this is the demographic situation in question that remains, somewhat different before World War II as Sijarina and Đulekari were villages with mixed populations, even in this latter settlement were many Serb families, and now the majority is made up of Albanians.]"

- Kamusella, Tomasz. The Dynamics of the Policies of Ethnic Cleansing in Silesia in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Web open access Archived 24 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Steinmetz, George (Winter 2005). "The First Genocide of the 20th Century and its Postcolonial Afterlives: Germany and the Namibian Ovaherero". Journal of the International Institute. 12 (2).

- Dr Jürgen Zimmerer and Prof. Benyamin Neuberger. "HERERO AND NAMA GENOCIDE". The Combat Genocide Association.

- "Herero Revolt 1904–1907". South African History Online. March 2011.

- Staff Reporter (March 1998). "Herero genocide – the facts and the criticisms". Mail & Guardian – Africa's Best Read.

- Emran Qureshi, Michael A. Sells. The New Crusades: Constructing the Muslim Enemy, p. 180

- Downes. Targeting Civilians in War. Cornell University Press.

- Lieberman, Benjamin (16 December 2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 75, 61. ISBN 9781442230385.

- Mozjes, Paul. Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the Twentieth Century. p. 34, 35

- Stark, Laura, ed. (30 May 2016). "Memory, heritage and ethnicity: Constructing identity among the Istanbul-based orthodox Bulgarians". Ethnologia Europaea. Vol. 46. Museum Tusculanum Press. doi:10.16995/ee.1180. ISBN 9788763544870.

- Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich at War: 1939–1945. p. 146.

- Ther, Philipp; Kreutzmüller, Charlotte (6 August 2023). The Dark Side of Nation-States. Berghahn Books. p. 61. doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qd3ng. ISBN 9781782383024. JSTOR j.ctt9qd3ng.

- Knight, Robert. Ethnicity, Nationalism and the European Cold War, p. 96

- Akcam, Taner (22 November 2017). "The Anatomy of Religious Cleansing: Non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire (1914—1918)". The Future of Religious Minorities in the Middle East. Lexington Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4985-6197-6.

- Bjørnlund, Matthias (2008). "The 1914 cleansing of Aegean Greeks as a case of violent Turkification". Journal of Genocide Research. 10 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1080/14623520701850286. S2CID 72975930.

- "Armenia: The Survival of A Nation" by Christopher J. Walker, Croom Helm (Publisher) London 1980, pp. 200–203

- The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915–1916: Documents Presented to Viscount Grey of Falloden by Viscount Bryce, James Bryce and Arnold Toynbee, Uncensored Edition. Ara Sarafian (ed.) Princeton, New Jersey: Gomidas Institute, 2000. ISBN 0-9535191-5-5, pp. 635–649

- Der Matossian, Bedross (28 July 2017). "Venturing into the Minefield: Turkish Liberal Historiography and the Armenian Genocide". The Armenían Genocíde. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315131016. ISBN 978-1-315-13101-6.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2009). "Truth in Telling: Reconciling Realities in the Genocide of the Ottoman Armenians". The American Historical Review. 114 (4): 930–946. doi:10.1086/ahr.114.4.930.

- Kort, Michael (2001). The Soviet Colossus: History and Aftermath, p. 133. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-7656-0396-9.

- Hosking, Geoffrey A. (2006). Rulers and Victims: The Russians in the Soviet Union. Harvard University Press. p. footnote 29. ISBN 0-674-02178-9. The footnote ends with a reference: Holquist, Peter (1997). "Conduct Merciless, Mass Terror Decossackization on the Don, 1919". Cahiers du Monde Russe: Russie, Empire Russe, Union Soviétique, États Indépendants. 38 (38): 127–162. doi:10.3406/cmr.1997.2486.

- Gingeras, Ryan (26 February 2009). Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire 1912-1923. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-160979-4.

Most of the Christian irregulars were involved in the ethnic cleansing of the Gemlik–Yalova– ̇İzmit region.

- Sassounian, Harut (28 June 2009). "Turkish Prime Minister Admits Ethnic Cleansing". Huffington Post.

- Geniki Statistiki Ypiresia tis Ellados (Statistical Annual of Greece), Statistia apotelesmata tis apografis sou plithysmou tis Ellados tis 15–16 Maiou 1928, pg.41. Athens: National Printing Office, 1930. Quoted in Kontogiorgi, Elisabeth (2006-08-17). Population Exchange in Greek Macedonia: The Forced Settlement of Refugees 1922–1930. Oxford University Press. pp. 96, footnote 56. ISBN 978-0-19-927896-1.

- Cardoza, Anthony L. (2006). Benito Mussolini: the first fascist. Pearson Longman. p. 109. ISBN 9780321095879.

- Lahtinen, Anja (December 2010). "GOVERNANCE MATTERS – CHINA'S DEVELOPING WESTERN REGION WITH A FOCUS ON QINGHAI PROVINCE" (PDF). HELDA – Digital Repository of the University of Helsinki.

- Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 273. ISBN 0-7425-1144-8. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Chung-kuo fu li hui, Zhongguo fu li hui (1961). China reconstructs, Volume 10. China Welfare Institute. p. 16. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- David S. G. Goodman (2004). China's campaign to "Open up the West": national, provincial, and local perspectives. Cambridge University Press. p. 204. ISBN 0-521-61349-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Shail Mayaram (2009). The other global city. Taylor & Francis US. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-415-99194-0. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- Shail Mayaram (2009). The other global city. Taylor & Francis US. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-415-99194-0. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- Gratton, Brian; Merchant, Emily (December 2013). "Immigration, Repatriation, and Deportation: The Mexican-Origin Population in the United States, 1920-1950" (PDF). Vol. 47, no. 4. The International migration review. pp. 944–975.

- Hoffman, Abraham (1 January 1974). Unwanted Mexican Americans in the Great Depression: Repatriation Pressures, 1929–1939. VNR AG. ISBN 9780816503667.

- Balderrama, Francisco E.; Rodriguez, Raymond (1 January 2006). Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s. UNM Press. ISBN 9780826339737.

- Johnson, Kevin R. (2005). "The Forgotten Repatriation of Persons of Mexican Ancestry and Lessons for the War on Terror". Pace Law Review. 26: 1. doi:10.58948/2331-3528.1147. S2CID 140417518.

- Kim, Alexander (2012). "The Repression of Soviet Koreans during the 1930s". The Historian. 74 (2): 267–285. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.2012.00319.x. JSTOR 24455386. S2CID 142660020.

- "Genocide of European Roma (Gypsies), 1939–1945".

- "The Holocaust in Romania".

- "The Holocaust in Hungary: Frequently Asked Questions — United States Holocaust Memorial Museum".

- "Bulgaria".

- Hayden, Robert M. (1996). "Schindler's Fate: Genocide, Ethnic Cleansing, and Population Transfers". Slavic Review. 55 (4): 727–748. doi:10.2307/2501233. JSTOR 2501233.

- Korb, Alexander (2010). "Nation-Building and Mass Violence: The Independent State of Croatia, 1941–45". The Routledge History of the Holocaust. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203837443-29/nation-building-mass-violence-alexander-korb (inactive 25 October 2023). ISBN 978-0-203-83744-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2023 (link) - Geiger 2012, p. 86.

- Žerjavić 1995, pp. 556–557.

- Human Rights Watch (1991). "Punished Peoples" of the Soviet Union: The Continuing Legacy of Stalin's Deportations" (PDF). New York.

- Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1159. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177. JSTOR 826310. S2CID 43510161. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2018.

- Baltsiotis, Lambros (2011). "The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece. The grounds for the expulsion of a "non-existent" minority community". European Journal of Turkish Studies. Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey (in French) (12). doi:10.4000/ejts.4444. ISSN 1773-0546.

- Cambridge Journals Online – Central European History – Abstract – National Mythologies and Ethnic Cleansing: The Expulsion of Czechoslovak Germans in 1945. Journals.cambridge.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Cambridge Journals Online – The Review of Politics – Abstract – The Expulsion of the Germans from Hungary: A Study in Postwar Diplomacy. Journals.cambridge.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Diasporas and Ethnic Migrants: Germany, Israel, and Post-Soviet Successor ... – Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Partition India :: Twentieth century regional history :: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Ahmed, Ishtiaq (March 2002). "The 1947 Partition of India: A Paradigm for Pathological Politics in India and Pakistan". Asian Ethnicity. 3 (1): 9–28. doi:10.1080/14631360120095847. S2CID 145811519. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- Barbara D. Metcalf; Thomas R. Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of India (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0521682251.

The outcome, akin to what today is called 'ethnic cleansing', produced an Indian Punjab 60 per cent Hindu and 35 per cent Sikh, while the Pakistan Punjab became almost wholly Muslim.

- A.G. Noorani (13 September 2018). "Why Jammu erupts?". Frontline.

- "The killing fields of Jammu: How Muslims became minority in the region". Scroll.in. 10 July 2016.

- Pappé, Ilan (2006). "The 1948 Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine". Journal of Palestine Studies. 36 (1): 6–20. doi:10.1525/jps.2006.36.1.6. hdl:10871/15208. ISSN 0377-919X. JSTOR 10.1525/jps.2006.36.1.6. S2CID 155363162.

- "From "Denying Human Rights and Ethnic Identity" series of Human Rights Watch" Archived 7 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine Human Rights Watch, 2 July 2006.

- https://www.hsje.org/Egypt/the_plight_of_%20jews_in_egypt.pdf American Jewish Committee. March 1957.

- Maldonado, Pablo Jairo Tutillo (27 March 2019). "How should we remember the forced migration of Jews from Egypt?". UW Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- "The Jews driven out of homes in Arab lands". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- "Jewish Refugees from the Middle East and North Africa - Wednesday 19 June 2019 - Hansard - UK Parliament". hansard.parliament.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- Trueman, Chris N. (26 May 2015). "The United Nations and the Congo". The History Learning Site. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Smith, Martin (1991). Burma – Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London, New Jersey: Zed Books. pp. 43–44, 98, 56–57, 176. ISBN 0-86232-868-3.

- Mukhopadhyay, Kali Prasad (2007). Partition, Bengal and After: The Great Tragedy of India. New Delhi: Reference Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-81-8405-034-9.

- Ray, Jayanta Kumar (September 1968). Democracy and Nationalism on Trial (First ed.). Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study. p. 216.

- Lahiry, Pravash Chandra (1964). India Partitioned And Minorities in Pakistan. Writer's Forum. pp. 54–55.

- "Annual Report of the Ministry of External Affairs for 1962-63". Ministry of External Affairs, India. p. 20. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "Bloodbath Against Non-Muslims in Undivided Bengal – The Story That Needs to Be Told". 24 December 2019.

- Roy, Tathagata (2001). My People, Uprooted: A Saga of the Hindus of Eastern Bengal. Kolkata: Ratna Prakashan. pp. 220–221. ISBN 81-85709-67-X.

- Bhattacharyya, S.K. (1987). Genocide in East Pakistan/Bangladesh. Houston: A. Ghosh. p. 105. ISBN 0-9611614-3-4.

- "none". The Daily Ittefaq. Dhaka. 18 January 1964.

- Monaghan, Paul (23 April 2016). "Britain's shame: the ethnic cleansing of the Chagos Islands". Politicsfirst.org.uk. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Taylor, Ollie (15 July 2017). "The ethnic cleansing of the Chagos Islands". Medium.com. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Oeter, Stefan (2014). "Recognition and Non-Recognition with Regard to Secession". In Walter, Christian; von Ungern-Sternberg, Antje; Abushov, Kavus (eds.). Self-determination and Secession in International Law. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-870237-5.

The Turkish army engaged in an exercise of 'ethnic cleansing' and expulsed more or less all Greek Cypriots from the North with brute force.

- Ó Cathaoir, Brendan (20 July 2004). "Invasion 30 years ago still scars Cyprus". Irish Times.

The occupied area was ethnically cleansed of its Greek Cypriot population: about 142,000 people – 23 per cent of the island's population – were driven from their homes and became refugees in their own country.

- "'Ethnic cleansing', Cypriot style". The New York Times. 5 September 1992. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. "WGIP: Side event on the Hmong Lao, at the United Nations". Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- Jane Hamilton-Merritt, Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the Secret Wars for Laos, 1942–1992 (Indiana University Press, 1999), pp337-460

- Forced Back and Forgotten (Lawyers' Committee for Human Rights, 1989), p8.

- "Cambodia – Population". Library of Congress Country Studies.

- Cambodia – the Chinese. Library of Congress Country Studies.

- "Moshahida Sultana Ritu (12 July 2012). "Ethnic Cleansing in Myanmar". The New York Times.

- Peter Ford (12 June 2012). "Why deadly race riots could rattle Myanmar's fledgling reforms". The Christian Science Monitor.

- Kamusella, Tomasz. 2018. Ethnic Cleansing During the Cold War: The Forgotten 1989 Expulsion of Turks from Communist Bulgaria (Ser: Routledge Studies in Modern European History). London: Routledge. ISBN 9781138480520.

- "Bulgaria MPs Move to Declare Revival Process as Ethnic Cleansing - Novinite.com - Sofia News Agency". www.novinite.com.

- "Парламентът осъжда възродителния процес - Actualno.com". Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2015. Парламентът осъжда възродителния процес

- "Forced displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict: return and its alternatives" (PDF). Conciliation Resources. August 2011.

- De Waal, Black Garden, p. 285

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld – Chronology for Lhotshampas in Bhutan".

- "Refugees warn of Bhutan's new tide of ethnic expulsions". The Guardian. 20 April 2008

- Gokhman, M. "Карабахская война", [The Karabakh War] Russkaya Misl. 29 November 1991.

- Доклад Правозащитного центра общества "Мемориал" НАРУШЕНИЯ ПРАВ ЧЕЛОВЕКА В ХОДЕ ПРОВЕДЕНИЯ ОПЕРАЦИЙ ВНУТРЕННИМИ ВОЙСКАМИ МВД СССР, СОВЕТСКОЙ АРМИЕЙ И МВД АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНА В РЯДЕ РАЙОНОВ АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНСКОЙ РЕСПУБЛИКИ В ПЕРИОД С КОНЦА АПРЕЛЯ ПО НАЧАЛО ИЮНЯ 1991 ГОДА

- Report by Professor Richard Wilson "On the Visit to the Armenian-Azerbaijani Border, May 25–29, 1991" Presented to the First International Sakharov Conference on Physics, Lebedev Institute, Moscow on 31 May 1991.

- Melkonian. My Brother's Road, p. 186.

- Burmese exiles in desperate conditions, BBC News

- Steven J. Rosen (2012). "Kuwait Expels Thousands of Palestinians". Middle East Quarterly.

From March to September 1991, about 200,000 Palestinians were expelled from the emirate in a systematic campaign of terror, violence, and economic pressure while another 200,000 who fled during the Iraqi occupation were denied return.

- Le Troquer, Yann; Al-Oudat, Rozenn Hommery (1999). "From Kuwait to Jordan: The Palestinians' Third Exodus". Journal of Palestine Studies. 28 (3): 37–51. doi:10.2307/2538306. JSTOR 2538306.

- Human Rights Watch/Helsinki, RUSSIA. THE INGUSH-OSSETIAN CONFLICT IN THE PRIGORODNYI REGION, May 1996.

- Russia: The Ingush-Ossetian Conflict in the Prigorodnyi Region (Paperback) by Human Rights Watch Helsinki Human Rights Watch (April 1996) ISBN 1-56432-165-7

- "Milosevic: Important New Charges on Croatia". Human Rights Watch. 21 October 2001. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- "The legal battle ahead". BBC News. 8 February 2002. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Croatia and Serbia Sue Each Other for Genocide Text". 3 March 2014.

- Naegele, Jolyon (21 February 2003). "Serbia: Witnesses Recall Ethnic Cleansing As Seselj Prepares For Hague Surrender". Radio Free Europe. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "UN tribunal upholds 35-year jail term for leader of breakaway Croatian Serb state". UN News. 8 October 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "Convicted Croatian Serb ex-leader commits suicide before he was to testify at UN court". UN News. 6 March 2006. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "APPEALS CHAMBER REVERSES ŠEŠELJ'S ACQUITTAL, IN PART, AND CONVICTS HIM OF CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY". United Nations Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals. 11 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "Serbia: Conviction of war criminal delivers long overdue justice to victims". Amnesty International. 11 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Isayev, Ismayil; Abilov, Shamkhal (December 2016). "The Consequences of the Nagorno–Karabakh War for Azerbaijan and the Undeniable Reality of Khojaly Massacre: A View from Azerbaijan". Polish Political Science Yearbook. 45: 291–303. doi:10.15804/ppsy2016022.

- Hakobyan, Tatul (February 1992). "Khojaly: The Moment of Truth" (PDF). Armenian Cause Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2018 – via arfd.am.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan Department for Analysis and Strategic Studies (February 2017). "KHOJALY GENOCIDE: 25 YEARS OF INJUSTICE AND IMPUNITY" (PDF). astana.mfa.gov.az/.

- Committee on Foreign Relations, US Senate, The Ethnic Cleansing of Bosnia-Hercegovina, (US Government Printing Office, 1992)

- "Bosnia: Dayton Accords". www.nytimes.com.

- Wren, Christopher S. (24 November 1995). "Resettling Refugees: U.N. Facing New Burden". The New York Times.

- Tony Barber, Andrew Marshall (21 September 1994). "Serbs expelled almost 800,000 Muslims". The Independent. London. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "ICTY: Naletilic and Martinovic (IT-98-34-PT)" (PDF).

- "UN tribunal transfers former Bosnian Serb leader to UK prison". UN News. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "Bosnian Serb politician convicted by UN tribunal to serve jail term in Denmark". UN News. 4 March 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Former high-ranking Bosnian Serbs receive sentences for war crimes from UN tribunal". UN News. 27 March 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "UN tribunal sentences former Bosnian Serb president to 11 years". UN News. 27 February 2003. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "UN hails conviction of Mladic, the 'epitome of evil,' a momentous victory for justice". UN News. 22 November 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Leutloff-Grandits, Carolin (2006). Claiming Ownership in Postwar Croatia: The Dynamics of Property Relations and Ethnic Conflict in the Knin Region. Münster, Germany: LIT Verlag. p. 119. ISBN 978-3-8258-8049-1.

- Bonner, Raymond (21 March 1999). "War Crimes Panel Finds Croat Troops 'Cleansed' the Serbs". The New York Times.

- Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the Twentieth Century. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-44220-663-2.

...by 1995 the Croat army had driven out the Serb forces and population from.. Krajina (Operation Oluja [Storm])... This was the single largest ethnic cleansing of the wars of the 1990s.

- Ingrao, Charles W.; Emmert, Thomas Allan (2013). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. Purdue University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-55753-617-4.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–136. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (19 November 2012). "Vindication or travesty ? Operation Storm's Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markac acquitted". Greatersurbiton.wordpress.com. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "Judgement Summary for Gotovina et al" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 15 April 2011.

- Borger, Julian (16 November 2012). "War crimes convictions of two Croatian generals overturned". The Guardian.

- "Gotovina and Markac, IT-06-90-A" (PDF). ICTY.org. International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 16 November 2012. pp. 30–34.

- "Five Senior Serb Officials Convicted of Kosovo Crimes, One Acquitted". ICTY. 26 February 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Šainović et al., Case Information Sheet" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- Bugajski, Janusz (2002). Political Parties of Eastern Europe: A Guide to Politics in the Post-Communist Era. New York: The Center for Strategic and International Studies. p. 479. ISBN 1-56324-676-7.

- "Kosovo/Serbia: Protect Minorities from Ethnic Violence". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- Abuses against Serbs and Roma in the New Kosovo, Human rights watch

- Bookman, Milica Zarkovic, The Demographic Struggle for Power, (p. 131), Frank Cass and Co. Ltd. (UK), (1997) ISBN 0-7146-4732-2

- "Voice of America (18 October 2006)". Archived from the original on 22 October 2007.

- "Error". www.unhcr.org.

- Pallone introduces resolution condemning Human rights violations against Kashmiri Pandits, United States House of Representatives, 15 February 2006

- Expressing the sense of Congress that the Government of the Republic of India and the State Government of Jammu and Kashmir should take immediate steps to remedy the situation of the Kashmiri Pandits and should act to ensure the physical, political, and economic security of this embattled community. HR Resolution 344 Archived 13 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, United States House of Representatives, 15 February 2006

- Senate Joint Resolution 23, 75th OREGON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY—2009 Regular Session Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Anti-Chinese riots continue in Indonesia, 29 August 1998, CNN

- Wages of Hatred, Business Week

- Administrator. "Behind Ethnic War". www.globalpolicy.org.

- "DR Congo pygmies 'exterminated'". BBC News. 6 July 2004.

- "DR Congo pygmies appeal to UN". BBC News. 23 May 2003.

- "The New York Times - Breaking News, US News, World News and Videos". www.nytimes.com.

- "7.30 Report – 8/9/1999: Ethnic cleansing will empty East Timor if no aid comes: Belo". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 23 May 2023.

- The New Book of Knowledge (Grolier), volume T, p. 228 (2004)

- Moore, Charles (29 October 2005). "Bushmen forced out of desert after living off land for thousands of years". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 29 October 2005.

- "African Bushmen Tour U.S. to Fund Fight for Land". news.nationalgeographic.com.

- Price, Tom. "Exiles of the Kalahari".

- International, Survival. "UN condemns Botswana government over Bushman evictions".

- Collins, Robert O., "Civil Wars and Revolution in the Sudan: Essays on the Sudan, Southern Sudan, and Darfur, 1962–2004", (p. 156), Tsehai Publishers (US), (2005) ISBN 0-9748198-7-5 .

- "Arabs pile into Darfur to take land 'cleansed' by janjaweed". Archived from the original on 18 December 2007.

- "Culture and Cultural Heritage at the Council of Europe – Homepage" (PDF). Culture and Cultural Heritage.

- "KOSOVO FACT FINDING MISSION – AUGUST, 2004" (PDF).

- "US". Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008.

- "There is ethnic cleansing" Archived 12 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Damon, Arwa. "Iraq refugees chased from home, struggle to cope". www.cnn.com.

- U.N.: 100,000 Iraq refugees flee monthly. Alexander G. Higgins, Boston Globe, 3 November 2006.

- Wong, Edward (30 May 2007). "In North Iraq, Sunni Arabs Drive Out Kurds". The New York Times.

- "Christians, targeted and suffering, flee Iraq – USATODAY.com". www.usatoday.com.

- AsiaNews.it. "IRAQ Terror campaign targets Chaldean church in Iraq". www.asianews.it.

- "UNHCR | Iraq". Archived from the original on 29 November 2008.

- "Christians live in fear of death squads". IRIN. 19 October 2006.

- Steele, Jonathan (30 November 2006). "Jonathan Steele: While the Pope tries to build bridges in Turkey, the precarious plight of Iraq's Christians gets only worse". The Guardian.

- "Iraq's Mandaeans 'face extinction'". BBC News. 4 March 2007.

- "Yazidis fear annihilation after Iraq bombings". 16 August 2007. Archived from the original on 18 August 2007.

- Ann McFeatters: Iraq refugees find no refuge in America. Seattle Post-Intelligencer 25 May 2007.

- "Niger starts mass Arab expulsions". BBC News. 26 October 2006.

- "Niger's Arabs say expulsions will fuel race hate". alertnet.org. Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 November 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2011.